In light of the looming Combatting Misinformation and Disinformation ('M.A.D) Bill,[1] Prof. Andrea Carson and Dr Max Grömping's paper looks into the real state of the information environment in Australia in comparison to other countries, focusing on the exaggerated perceived threat of so-called misinformation and disinformation on public information quality and how any harmful effects might be combatted without draconian censorship laws.

In light of the looming Combatting Misinformation and Disinformation ('M.A.D) Bill,[1] Prof. Andrea Carson and Dr Max Grömping's paper looks into the real state of the information environment in Australia in comparison to other countries, focusing on the exaggerated perceived threat of so-called misinformation and disinformation on public information quality and how any harmful effects might be combatted without draconian censorship laws.

The full paper, entitled, ‘Measuring, monitoring and diagnosing the impact of mis /dis information to support future (non-legislative) policy development,’ is at Australian Resilient Democracy Research and Data Network | Discussion Paper 2.[2]

Carson and Grömping cite three imperfect ways of defining the problematic terms: 'misinformation,' 'disinformation,' and 'malinformation.

"[..]Wardle and Derakhshan (2017) outline three concepts: misinformation, defined as false content that is spread without the intention of causing harm; disinformation, considered as false content that is spread with the intention of causing harm; and a third category, malinformation, defined as truthful content spread also with the intention to damage or cause harm such as malicious rumours (see also Carson and Wright 2023, 2). [...]"(p.1)

They suggest that the problem is greatly exaggerated (p.4):

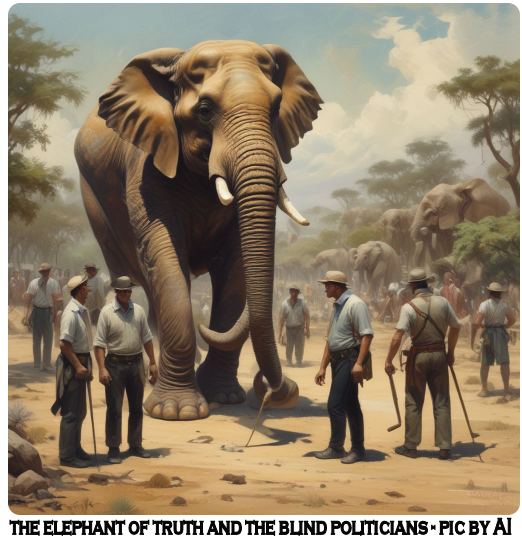

men, some who carry sticks and one who also has a golf club seems fittingly confused.

Research using digital trace data suggests that globally, contrary to widespread perceptions, the information environment is not ‘rife’ with misinformation. Public discourse across countries sometimes overstates exposure to harmful content by relying on aggregate statistics without appropriate population-level denominators, individual-level statistics skewed by extreme values, and engagement metrics that do not accurately represent actual exposure levels (Budak et al. 2024). Rather, false and misleading information represents a miniscule portion of people’s overall information diet. In the U.S. context it constitutes less than 1% of regular news consumption and less than 0.1% of total media consumption (Waes, Rothschild, and Mobius 2021; Grinberg et al. 2019). One key reason for low prevalence and low exposure is that news itself makes up only a tiny fraction of people’s overall media consumption, between 14% of Americans’ media diet and 3% of French internet usage – with misinformation representing just 0.15% and 0.16% respectively (Allen et al. 2020; Cordonier and Brest 2021). In Australia, analysis of the 2022 federal Election suggested that Election news constituted a fragment (17.7%) of Australian’s overall media consumption online (Carson and Jackman, 2022: 143)

Sadly, but not surprisingly, they find that estimates of misinformation circulation "are higher in studies that include misleading information spread by politicians and mainstream media." (p.4) Note that the proposed impending censorship legislation exempts government and legacy media from examination.

The main election-news content consumers tend to be older, more politically engaged people, and the rise of the internet means that they can find more of what they want.

These trends, however, highlight the problems of defining 'misinformation,' because one person's information is another person's misinformation, and where you stand politically may make all the difference. Not considered, apparently, in the study, is people who may want to look at all sides of an argument before making up their minds, but the research paper does note that "on average and across countries, true news items are perceived as accurate at a much higher rate than false news items."

Predictably, social and survival factors play a big role in what we may believe in a contentious issue:

"Research in the Australian context specifically shows that the strongest correlates of conspiracy beliefs are social and existential factors, rather than critical thinking or rational accuracy-driven motives (Marques et al. 2021)."

After all, humans will go to war based on how a conflict is presented to them in the mainstream media - be that media the Church Pulpit, or Australia's ABC, and they screen out contrary information. That is why sociology as a discipline has as its foundation the notion that social constraints, for humans, are as real as material environmental factors. We will die for an idea, and herds of us will face death and maiming to eliminate 'mad dictators,' on the say-so of elites in whom we notoriously have little confidence. Perception is almost everything.

On pages 6-7 the authors review three 'misinformation' cases that involved government and political parties. They write:

"The three studies identify the role that political elites and both mainstream and social media play in spreading and giving salience to misinformation that has the potential to harm public perceptions of election integrity. Without appropriate sanctions these actors will continue to weaponise false narratives to gain political advantage, enabled by the very same institutions that lose (more) trust with each iteration of misinformation."

These political misinformation cases were: The 2016 federal election 'Mediscare Campaign,' where the Labor Party conducted a 'misleading narrative' that the Coalition was going to privatise Medicare; the 2019 federal election Death Tax scare, where the federal Coalition falsely claimed a Labor government would introduce an inheritance tax; and various campaigns against the 2023 Voice to Parliament referendum, raising questions, among others, about the process and the AEC. Read more in the paper itself.

Among the authors' conclusions about these examples are that more public money should be available to help researchers access big data resources, which are very expensive. Fair enough; the field requiring analysis is enormous.

As they have noted earlier in the paper, there is not a lot of research on these issues. This lack of research strikes me as ironic to the point of damning, given the emphasis and urgency that the Liberal Government last year, and the Federal Labor Government this year, have given to their respective, almost identical censorship projects. Do we really need actual disinformation or misinformation to undermine trust in our political elite and their media-pulpits?

Parallax social universe

While the paper is informative and welcome, I find its recommendations lacking. Although they have effectively highlighted the role of government and elite sources of misinformation, the authors are of necessity socially constrained to arguing from within a specific ideological or institutional framework. We live in a parallax social universe, where facts change according to your viewpoint. They are inside the official fact-checking church of designated correct information, thus operating under establishment rules, which limit the ability to challenge foundational concepts or propose radical changes. This mostly leads to recommendations that reinforce the status quo rather than questioning the underlying principles, or which dance around the issues. This is why you need people outside the church to challenge the arbitrary notion of angels rather than dispute how many might dance upon a pin head, or tree-huggers to point out to economists that when they externalise the environment in a profit and loss statement, the environment does not actually go away, and may reappear as an act of god when you try to claim insurance. And, just as we need designated 'mad dictators' in distant regions so that we can go to war with them and steal their resources, you need internet activists to give you access to hear the other side so that you may decide not to enlist and to save your life instead. We need voices outside the tent to challenge unrealistic laws that aim to consolidate power rather than protect truth and, of course, power will call those voices Disinformation, Misinformation and Malinformation and say we need protection from them.

Promote Hansard and other Candobetter dot net solutions

Here is what I would suggest:

1. Promote and use Hansard records of all parliamentary debates and activities as the main political news, uncensored. Then promote free discussion of these on a new Hansard internet platform.

2. Renovate the Australian education systems to re-prioritise clear-thinking and writing.

3. Encourage students to debate at all levels.

4. Teach cartooning, which points out fundamental assumptions.

5. Encourage the use of independent internet publications rather than social platforms.

6. Encourage news and information sourcing from all over the world.

7. Flag high-traffic topics as likely to be weaponised by governments and corporations

8. Keep tabs on where money is made by information carriers

9. Link newsmedia stories about product and investment to the corresponding sharemarket performance as a way to detect vested interest in reporting

10. Learn to detect how some publications cause you an emotional response

Please feel free to criticise my suggestions in the comments area. Send an article, if you wish.

NOTES:

[1] Communications Legislation Amendment (Combatting Misinformation and Disinformation) Bill 2024

[2] Carson. A., and Grömping, M., (2024), ‘Measuring, monitoring and diagnosing the impact of mis /dis information to support future (non-legislative) policy development’ Australian Resilient Democracy Research and Data Network Discussion Paper 2, Australian National University. Australian Resilient Democracy Research and Data Network | Discussion Paper 2.)

Add comment