When the Wheels fell Off

The 100 years from 1870 is described as the innovation century in which there more more inventions, starting coincidentally with the light bulb, than in the rest of mankind's history. For the most part their roll-out into society was slow enough to dampen the impact of the invention. Electricity, for instance, wasn't connected fully in Australia until 1989. But for me, one event stood out, and that occurred on the 4th of October 1957, just before my birthday.

The 100 years from 1870 is described as the innovation century in which there more more inventions, starting coincidentally with the light bulb, than in the rest of mankind's history. For the most part their roll-out into society was slow enough to dampen the impact of the invention. Electricity, for instance, wasn't connected fully in Australia until 1989. But for me, one event stood out, and that occurred on the 4th of October 1957, just before my birthday.

It was an event of enormous significance yet it is now almost completely forgotten. It changed the world – mostly for the better - in many ways, including preventing or lessening the chance of a nuclear war. It greatly enhanced the standing of science in government. It even made the moon landing possible.

At that time Australia was blessed with a prospective visit by a famous Rock star called Little Richard, (top song Good Golly Miss Molly,) but on that day he cancelled the tour and went into retirement in a monastery after he claimed to see a message from God in the sky.

In fact most Australians saw the same thing. The next night our family went out into the back yard of our house and, looking up into the sky, we saw a little aluminium sphere drift across the heavens. It was the world’s first satellite, launched into space by the Russians, and called Sputnik.

I can't remember anyone saying anything, but right then we realized that the cold war was not restricted to the northern hemisphere. Suddenly the concept of Mutually Assured Destruction, or MAD for short, was very close to home. The expression one flash and you’re ash had become reality.

For the United States this was a slap in the face - being beaten in science technology by a rival whose political philosophy they had scorned. Sputnik plunged Americans into a crisis of self-confidence, which included the idea that the country had grown lax with prosperity and had used science for frivolous purposes. This was so promoted by the media that people stopped buying luxury cars and Ford Edesel, an oversized vulgar yank-tank that aimed at the luxury market, went broke. One eminent scientist took advantage of the hysteria to proclaim: "Teach Science or Teach Russian."

It would have to be the slogan of the century, because by golly Ms Molly, it worked. Congress responded with the National Defence Education Act, which increased funding for education at all levels, including low-interest student loans to college students, with the focus on scientific and technical education. They enacted reforms in science and engineering so that their nation could regain technological advantages they had lost to the Soviets.

What was most fascinating, however, was that there were no dissenting voices. This was a universal movement: politicians saw they were on a winner and no one was crying caution. Science rules OK?

In the US, schools now placed new emphasis on the process of inquiry, independent thinking, and the challenging of long-held assumptions. Laboratory science was stressed, urging a hands-on learning approach. The emphasis moved from teaching facts to fundamental principles. Children could no longer be educated traditionally and Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, which had been successfully kept out of many US classrooms until late 1957, found a place in high school biology textbooks.

In Australia reactions to Sputnik were more pragmatic. The university system had been undergoing reform since 1956 and funding was increased by 300% in just two years to 1960. This was used to promote higher education and research across a broad range of disciplines, not solely to enable government-determined scientific goals. We did however become the third nation to launch a locally manufactured satellite in November 1967.

This was not a science renaissance but rather a re-imagining of science, which people saw as something that had been misdirected and mismanaged. The Science of the ICBM for nuclear weapons had become the pathfinder for space travel and carried the public along with it. Everyone wanted to be a rocket scientist, interest in astronomy boomed and, less than four years later, John Kennedy set out to land man on the moon.

But then something went wrong: science was sidelined, markets and money dominated government policy. So much so, that in 1990, Barry Jones AO, the science minister in the Hawke/Keating Labor government, announced that the crowning scientific achievement of his government was the return of Haley's comet. Yes, he was being sarcastic.

The Abbott government didn't even bother to have a science minister and cut funding for the CSIRO, the Climate Change Authority and many NGO's. Funding to the ABC, TAFE, and Universities, has also been cut, with the later becoming highly dependent on full-fee paying overseas students. The Climate Commission and the National Water Commission were abolished and, in terms of expenditure on research, Australia was ranked 18th out of 20 OECD countries in 2013, and this dropped a further 10% by 2015. Among those scientists made redundant was CSIRO’s Dr. San Thang, who was part of a team listed as a Noble prize contender for his work in chemistry. The technology this team invented has been adopted by 60 companies and royalties generated from the technology are forecast to reach $32.2 million by 2021.

This change in policy was more than just austerity-related cost-cutting, as there was also increased spending on fossil fuel projects, such as carbon sequestration.

It was targeted assassination of a rival philosophy and included drastic changes to our society and the way it functioned.

Manufacturing was almost obliterated, consumerism was revered, and population was purposefully increased through high immigration and a baby bonus.

Land clearing increased, along with animal extinctions and greenhouse emissions.

Unemployment tripled, housing became unaffordable, along with more homelessness and congestion, while mortgage debt exploded - all of which was hailed as economic progress.

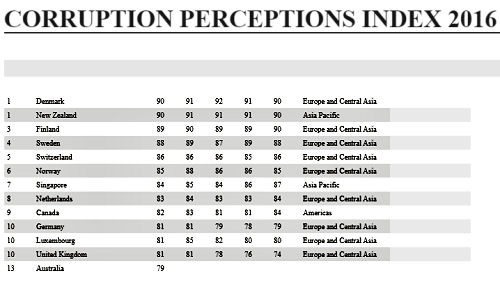

Along the way Australia's corruption ranking[1] dropped from 7th place in 2012 to 13th place in 2015 and we became dependent on imports for things we used to manufacture and paid for them mainly with exports of coal and iron ore.

Why?

Economists like to think of themselves as scientists, but really they are not seekers of fundamental truths, but more like lawyers, ready to argue a case regardless of its merits. Thus, all our banks have economists who will argue for among other things, deregulation. The Mineral council has economists who will argue that coal is more valuable to the economy than agriculture, while the property council will have economists telling us that housing price growth is good despite the misery it creates.

We even had economists for the farming lobby telling us that tackling obesity by cutting back on sugar would be bad for the economy and, alarmingly, there are economists in the media who repeat without question whatever line is being proposed, whilst others in universities teach the same nonsense to the next generation.

Just like defense lawyers these economists will defend their clients’ interests without shame or remorse, because in carefully selected economic terms, they can be shown to be correct - or at least beneficial - in growing the GDP. The fact that these organizations can afford to pay their economists very well also helps. Conscience is soothed by a religious-like commitment to growth economics, which is able to replace human or environmental empathy with the certainty of market supremacy. They hide the reality of their philosophy by use of econogabble, a language full of terminology only understood by other economists and then vague enough to have alternative meanings.

Of course, not all economists swallow the idea of market supremacy and there are some very clever human beings like the Australia Institute’s chief economist, Richard Denniss, whose views are called unconventional. But unconventional economists don't get employed by banks or governments - after all who wants someone telling you what you are doing is absurd, immoral, dangerous or even uneconomic? Growth economics has, not surprisingly, resulted in increasing levels of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) in the atmosphere, the growth of plastic in the oceans, and is instrumental, if not the direct cause, of every problem that plagues our society.

Now you may think I am biased, and of course you are right, but I am not alone. Even economists don't like economists. The great economist John Kenneth Galbraith once said:

"The only function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable."

Speaking of former US Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, another economist quipped:

"He was the greatest, the Maestro. Only if you look at his record, he was wrong about almost everything he ever predicted."

And that is part of the problem: Being wrong is not a sin if you are an economist. If a scientist had somehow missed something as bad as the GFC he would be forever shunned and his failure relentless analysed, so that it could not happen again.

Gordon Brown, the then UK’s prime minister, made a speech in June 2007 that was surely one of the greatest political and economic misjudgments among postwar politicians. He described his era as one that history will record as a new golden age for the City of London, praising the city’s creativity and ingenuity, just weeks before it collapsed into the GFC.

The UK tax payer was left with a one-sided exposure of £1.3 trillion in loans, investments, cash injections, and guarantees to the banking system, of which over £100bn may be lost forever. But all was not lost for Gordon Brown. Just 15 months later he was honored in the US as ‘Statesman of the Year’ by US former secretary of state Henry Kissinger.

After the GFC there was a great deal of criticism leveled at economists because for all their brilliant models and complex analyses, most economists completely failed to predict the disastrous outcome of the housing bubble. There were arguments as to whether the problem was an imperfect discipline or the result of human failures where biases on the part of many economists that made them blind to the truth. While there are always disagreements in the hard sciences, they're often less significant than some of the fundamentally different schools of thought within macroeconomics. You can have two equally respected economists perform two very well-thought out and rigorous analyses, but come to two different conclusions. That shouldn't be possible in a hard science. Facts plus analysis should lead to a conclusion that can be proven through observation.

The American Economic Association has proposed enhanced ethical standards for academic economists because, currently, they are not always required to explicitly state all sources of income and funding. This could cause bias to creep into their work, a process that was shown to have happened to financial advisers by the Australian Banking Royal Commission (4 December 2017 – 4 February 2019).

It could be argued that economic policy is more likely to contain bias due to outside influences than that of scientists, as there is often a lot of money at stake in either business or politics, depending on what the wisest economists in the land claim to be truth.

Logically then we should at least know who funds think tanks and Media columnists should disclose who they work for. We could go much further. Surely “ethical economics” is about using resources in a sustainable way.

Reducing carbon dioxide emissions, for instance, is certainly kinder to future generations than accepting the dictates of supply and demand.

Should we be importing products made by slave labor just because they are cheap? (Yes we do!)

Should we have traded with dictatorial regimes like Sadam Hussein's Iraq just because he bought our wheat?

Why do we support the arms trade, tobacco, alcohol, and gambling?

Well we do because, while third world countries get taken over by military coups, we were taken over by an economic coup d'état: a legal, constitutional seizure of power by a consortium of business groups who managed to pervert economics for their own benefit.

The way they achieved this can be understood by examining the words of David Suzuki, the world famous naturalist. He was three times voted the most trusted person in Canada. He summed up the economic strategy neatly, when he said:

“The economy — and the need to keep it strong and growing — has somehow become the most important aspect of modern life. Nothing else is allowed to rank higher. The economy is suffering; the economy is improving; the economy is stable or unstable — you’d think it was a patient on life support in an intensive-care unit from the way we anxiously await the next pronouncement on its health. But what we call the economy is nothing more than people producing, consuming and exchanging things and services.”

― David Suzuki, From Naked Ape to Superspecies: Humanity and the Global Eco-Crisis

It is apparent that this artificial obsession with a growth economy is a smoke screen that hides all other considerations, including human and environmental survival. I would argue that the wheels didn't fall off, they were stolen while we languished in complacency.

NOTES

[1] See the transparency Organisation at https://www.transparency.org/.

Recent comments