What does the future hold after COVID-19?

Will governments buy back vital resources and essential services from the embattled private sector, or will they allow the wealthy to pick up resources and monopolies cheaply, pressing the unemployed and endebted into slave-like conditions? Can we adapt to or avoid a future that appears to hold more and worse pandemics? If COVID-19 is a pandemic designed for elite purposes to cull the aged and weak, why have some governments tried to protect their vulnerable populations? We have obviously become too economically dependent on the model of continuous accelerated growth in human numbers and human activities globally to be able to protect ourselves from the pandemics that come with this economic model. At the same time the long-predicted oil-resources breakdown in supply is looming. Can any good come of this? Is this an opportunity?

Will governments buy back vital resources and essential services from the embattled private sector, or will they allow the wealthy to pick up resources and monopolies cheaply, pressing the unemployed and endebted into slave-like conditions? Can we adapt to or avoid a future that appears to hold more and worse pandemics? If COVID-19 is a pandemic designed for elite purposes to cull the aged and weak, why have some governments tried to protect their vulnerable populations? We have obviously become too economically dependent on the model of continuous accelerated growth in human numbers and human activities globally to be able to protect ourselves from the pandemics that come with this economic model. At the same time the long-predicted oil-resources breakdown in supply is looming. Can any good come of this? Is this an opportunity?

There are many reasons why a return to normality after COVID-19 is unlikely.

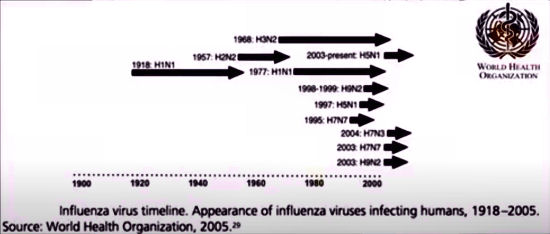

The underlying reason is the world-trend to a rapidly increasing incidence of serious new cross-species viral diseases (zoonoses). The most likely to produce epidemics and pandemics are those coming from large populations of domestic animals raised in intensive farming. Where once a zoonose would probably kill a novel host before the virus got a chance to jump to another individual, our new tendency to put livestock together in vast dense populations, along with our increasing tendency to live in vast dense populations ourselves, means that viruses can find multiple hosts to replicate in before their first host dies. Because we have no specific immune defenses against new zoonose viruses, they are much more likely to infect and kill us than longstanding human diseases.

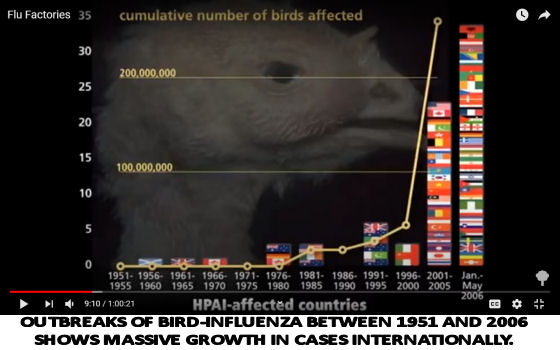

The embedded video below, Flu Factories, gives a graph between 1951 and 2006, showing that international progression of avian flus (among the most dangerous sources of zoonoses shared between pigs and birds), began building up with the institution of ever larger factory farms around the 1980s, and skyrocketed from the beginning of the 21st century.

It quotes a summary of the components of risk:

"- Increased demand for poultry products.-

- Increase in commercial peri-urban production.

- Increase in size of susceptible bird population in interface between extensive and intensive production.

- Increase in pathogenic virulence.

- Enhanced exposure in human population.

- Emergence of human pathogen.

- Human-to-human transmission pattern."

Dangerous divide between veterinary and human health sectors

Writing of the east in 2014, the World Health Organisation notes

"[The lack of] collaboration between the animal and human health sectors under the concept of “One Health” approach, which links the human with the animal health sector integrating the animal and human disease surveillance and response system that could, otherwise have helped controlling the zoonotic infections in animal reservoirs, enable early outbreak detection, and prevent deadly epidemics and pandemics." [Source: World Health Organisation: http://www.emro.who.int/fr/about-who/rc61/zoonotic-diseases.html [1]

This collaborative failure was and is also a major problem in the west, which, in the problem of COVID-19 control, amounts to a failure of communication in the context of dissimilar paradigms between the economic sector and the health sector. So, we have health professionals urging quarantine and business urging abandon of quarantine. We have obviously become too economically dependent on the model of continuous accelerated growth in human numbers and human activities globally to be able to protect ourselves from the pandemics that come with this economic model.

We could mitigate some of the risk within the current system

The above-cited World Health Organisation article http://www.emro.who.int/fr/about-who/rc61/zoonotic-diseases.html, which has a number of useful recommendations, correctly suggests that practising barrier nursing for all hospital patients would probably avoid almost all epidemics. Unfortunately, after antibiotics became widely available in the second half of the 20th century, hospitals all over the world became increasingly casual about infection control.

And we could return to reusable and locally produced hospital equipment: Post 1970s, with growing reliance on plastics and paper disposables, hospitals reduced their independent options by abandoning much in-house sterilisation of reusable instruments along with the laundering of reusable gowns, masks, and other protective equipment. As we know, the reliance on cheap imported sources for disposable equipment and tools has defined 21st century inadequacy in the management of COVID-19.

If we return to business as usual, however, with factory farming, clearing of wilderness, dense human populations, mass people movement internationally, and international trade, especially in animals and plants and their products, we will continue to experience pandemics. Some will have much higher fatality than COVID-19.

Politics of the current pandemic

The current pandemic is like a test of our social and political resilience, as well as our immune resilience, and its management presents something of an economic and moral puzzle, because of COVID-19's tendency to cull the weak and elderly - those people we have been taught by popular economic rationalism to blame all our woes on. (See /taxonomy/term/265 and /taxonomy/term/393.)

Whilst COVID-19 might look like a pandemic specially engineered on order from economic growth lobbyists who scapegoat the elderly and infirm, whilst encouraging mass migration of younger, haler, more fertile, cohorts, deemed economically more productive, this may only be coincidence.

Britain, Sweden and the United States have behaved more in tune with such economic ideologies, throwing their populations to the wolves, with cries of 'herd immunity'. Some governments, however, actually seem keen to avoid this opportunity of culling the elderly and infirm, when they have previously been so disparaging and cruel towards them. Australia and New Zealand are examples of such countries. What could explain this apparent humanity among an elite composed of economic rationalists, who generally only value their populace on condition of high productivity? Did politicians' wives, mothers, and fathers, get to them? Or is it because most at the top of government, political parties and corporations, and armies, are old themselves? Is it about the look of it, the desire to avoid mass graves and piles of cardboard coffins, US and Brazil-style? Is it about avoiding a glut of cheap housing and plunging property prices? Is it about avoiding total collapse of the hospital system, when surely they could have sequestered parts for themselves? Is it about avoiding economic collapse of old-age care businesses? Is it about currying favour with the elderly voter cohort? Is it about an exercise in preparing for the next worse epidemic? Is it about fear that the public will revolt at the prospect of their elders drowning in putrefacted lungs? Is it about shock at the prospect of shiny economic principles besmirched by medieval suffering and dirt?

It is certainly hard to figure out. Maybe what happened was that the pandemic took the mainstream press by surprise, and what we got, for a change, was a spontaneous response by the usually pre-programmed journalists. The elites, who are normally spoon-fed by the mainstream press, and protected from realising how angry some voters are, were panicked at the idea of popular rage. Usually they are protected from our perrenial rage at housing prices, homelessness, and rotten wars, because it is rarely reported and we have no independent public talking stick and means of assembly, so are unable to organise beyond indignation and that indignation is largely impotent because invisible to the political class. I take the near collapse of the anti-war movement as my model in this, since it appears to have been related to the mainstream press having simply stopped reporting on anti-war protests after the last big world protest against the Iraq war. Whilst I would like to believe that the alternative press can take care of reporting, it does seem that the mainstream still dictates the propaganda, hence what the elite politicians react to.

So, did politicians in Australia and New Zealand react to protect their vulnerable populations simply because they were afraid of public indignation? (All the while preaching against the use of protective face-masks.)

Or did the mainstream press jump at the opportunity to sow economic panic, so that media moguls and their friends could buy up assets and businesses cheap? And the politicians fell in with this plan under pressure to avoid public indignation about plague.

An engineered virus commissioned by elites?

There is little evidence to suggest that this virus was engineered, but a not insignificant number of people believe that elites would do so. After all, elites maintain massive military machines that design biological warfare, and constantly engineer the most brutal wars-for-profit in what has become the biggest game in town. But why would they or anyone need to commission a zoonose flu, when we have so many new zoonoses coming on board at faster and faster rates, from massive factory farms, and from the bush, as human population expands into what remains of forests and wildernesses, displacing exotic animals, and sucking the last endogamous and sedentary tribes into the vast human homogeneity hopper?

"During the past decades, many previously unknown human infectious diseases have emerged from animal reservoirs, from agents such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Ebola virus, West Nile virus, Nipah virus and Hanta virus. In fact, more than three quarters of the human diseases that are new, emerging or re-emerging at the beginning of the 21st century are caused by pathogens originating from animals or from products of animal origin. A wide variety of animal species, domesticated, peridomesticated and wild, can act as reservoirs for these pathogens, which may be viruses, bacteria, parasites or prions. Considering the wide variety of animal species involved and the often complex natural history of the pathogens concerned, effective surveillance, prevention and control of zoonotic diseases pose a real

challenge to public health." [Source: "Report of the WHO/FAO/OIE joint consultation on emerging zoonotic diseases," (May 2005) p.5. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/68899/WHO_CDS_CPE_ZFK_2004.9.pdf]

Why would elites encourage something that, anyway, threatens to put the kybosh on economic activity and mass people movement? Have they seen the writing on the wall, the collision of overpopulation with undersupply? Is this a way for them to lock populations down so they can control revolts against mass immigration? But the lock-downs stop mass immigration.

You could argue that big fish that survive will be able to buy up multiple businesses and assets dirt cheap, in the way that Mr Soros picks up currencies and coal mines cheaply in the wake of wars and climate activism. In the short-term, it would be hard to counter this one.

In the longer run, however, inevitably, more virulent viruses will have the effect of sparsening populations, ultimately making them less infective. Substantially sparser populations world-wide will really wreck the connective fibre of the international capitalist system, and will probably wreck national systems, sparing all but local systems. Depending on how much populations and global trade and travel are reduced, humans will spontaneously reorganise into small viscous populations, developing their own local immunities.

The elites, however, may well benefit from this too, on the way down. This would be because, if we spiral into depression, people will work for tiny wages, even for their keep, or as slaves, everywhere, creating local alternatives to both imported and outsourced cheap overseas labour.

Oil prices....

At the same time as the pandemic, the long-predicted oil-resources shortage is looming, although it is initially presenting as an oil-glut. Reduction in economic activity through mass quarantines has led to collapse in demand for petroleum. Since the 1970s, oil discovery and production have become increasingly difficult and costly. Easily drilled and pumped sources of crude have long given way to hard-to-access mixed liquids and gases, including fracked and vegetable ones. Oil exploration and production decline and stop in the absence of sufficient investment. Overleveraged companies fail under economic stress, especially with the kinds of costs involved in oil-exploration and exploitation. Countries dependent on oil-revenue descend into economic depression. Supply chains are disrupted by business failures. Machinery falls into disuse. Skills are lost or poached. Predators and competitors destroy oil-fields in order to privilege their own production recovery. Ultimately governments and conglomerates, including banks, will be able to buy up oil exploration and production cheap. Western governments have tended to enable corporations, to the detriment of economic and equitable supply, and have gone in with their war machines to destroy or wrest oil production from public companies in Iraq, Libya, Syria, Venezuela, etc. The stop and start mode is inherently costly and disruptive. Probably the only reliable mode of oil and gas production is by governments, which do not have to make a profit. As Colin Campbell wrote in the 1990s,

"The Soviets were very efficient explorers, as they were able to approach their task in a scientificmanner, being able to drill holes to gather critical information, whereas their Western counterparts had to pretend that every borehole had a good chance offinding oil." [Source: Colin Campbell, "The Caspian Chimera," Chapter 5, in Sheila Newman, Ed. The Final Energy Crisis, 2nd Ed., 2008]

Some possible solutions and adaptations

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed fundamental weaknesses in global supply system.The need for governments to take over outsourced services and resources in order to provide for vital needs reveals the fallacy of privatisation for profit, and exposes the notion of privatisation for 'efficiency' as laughable.

The failure of private businesses and corporations provides a serendipitous opportunity for governments to cheaply buy back vital resources, such as land, power and water, and essential services, like airlines, roads, hospitals, land-production and housing etc.

Deglobalisation of the economy means ending mass migration and foreign ownership of resources and essential services.

Without Australia's massive population growth, which relies on mass immigration, the land and housing sector would no longer support our huge and immensely costly private property and infrastructure development industry. Until Primeminister Menzies in the 1960s, who also encouraged mass immigration, government was the main land and housing production source.

Governments now have the opportunity to re-regulate land and other vital resource prices in order to reduce the cost of living and production, to get us through the coming economic depression, and beyond. Lower land-prices would mean more local ownership and the opportunity for more local food production, proportionately reducing the need for the cash economy. These changes would make it possible to reduce the hours of work that people need to earn a living and the need for consumerism to support more workers.

Governments should also be able to organise the share of essential work more equitably.

Populations in lock-down have had the opportunity to investigate the notion of leisure, the meaning of life, and even to smell the roses. Released from the treadmill, but at risk of their lives, more may have started to question the authority of the elites and be more willing to participate in political self-determination. Nonsensical advice about not wearing masks, which must have had fatal consequences, was given by the highest authorities in the land. Will this lead to wider public loss of blind faith in media-created and promoted figureheads, resulting in ordinary people doing their own research and testing and trusting their own judgement, finding leaders locally, rather than accepting the leadership choices and policy dictates of a distant political caste?

NOTES

[1] This paper is undated but appears under the "Comité régional » Sixty-first session," which made its annual report in December 2014.

Recent comments