Author and Chiari Syndrome sufferer, Rahael D'Alonzo, has written a fascinating personal account and investigation of this obscure, chameleon and pervasive syndrome, which often requires neurosurgery and may be life-threatening. His style is direct, his observations detailed and scientific, his accounts of human mismanagement of his diagnosis and treatment revealing but fair. His perspective is both useful and unusual because of his own background as a pharmaceutical research scientist and his strong personality and physical stamina. He has a sophisticated understanding of the United States health insurance industry.

Author and Chiari Syndrome sufferer, Rahael D'Alonzo, has written a fascinating personal account and investigation of this obscure, chameleon and pervasive syndrome, which often requires neurosurgery and may be life-threatening. His style is direct, his observations detailed and scientific, his accounts of human mismanagement of his diagnosis and treatment revealing but fair. His perspective is both useful and unusual because of his own background as a pharmaceutical research scientist and his strong personality and physical stamina. He has a sophisticated understanding of the United States health insurance industry.

Book Review:Raphael D'Alonzo, Contents under pressure: One man's struggle over Chiari Syndrome (Second Edition), Lulu Publishing, 2008

Chiari Malformation Syndrome

Author and Chiari Syndrome sufferer, Rahael D'Alonzo, has written a fascinating personal account and investigation of this obscure, chameleon and pervasive syndrome.

His style is direct, his observations detailed and scientific, his accounts of human mismanagement of his diagnosis and treatment revealing but fair.

Sudden overwhelming obsession with death

Shortly into D'Alonzo's book we find that the author puts his confidence in a priest after his life is suddenly rocked by shocking pain - out of the blue, but lasting only hours - and an obsession with death, and a craving for asparagus, which last for several months. It is 1980 and he is 27 years old. He thinks these may have been the first signs of Chiari Syndrome. Since D'Alonzo is a medical-pharmaceutical research scientist, his reliance on religious faith may seem rather odd to those of us unfamiliar with the pervasive force of religion in the US. One might perhaps have expected it more towards the middle of the book, perhaps nearly 20 years later, just before his brain surgery, when D'Alonzo was literally on his last legs - hardly able to walk, hardly sleeping, with little remaining muscular force. However, by that time D'Alonzo has placed himself at the mercy of medical practitioners and the United States "Health" system, which predictably took forever to diagnose him. There is an irony there, about the skills of priests and the skills of psychiatrists and medical doctors when dealing with the unusual.

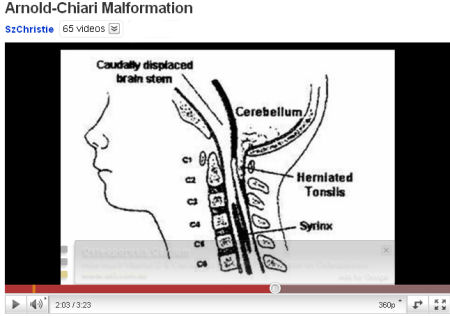

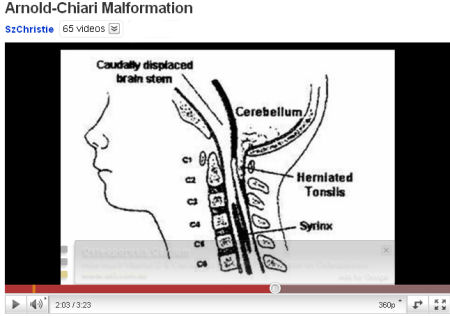

If you look for them, you will find other Chiari voices in different countries attempting to find understanding and to educate. Click on the picture above for a video about the disease by SzChristie, who is a Hungarian sufferer from Chiari Malformation Syndrome. She first became aware of the symptoms of the disease when she was 19 years old. Her channel on youtube seeks to help people suffering from other rare diseases as well as Chiari.

If you look for them, you will find other Chiari voices in different countries attempting to find understanding and to educate. Click on the picture above for a video about the disease by SzChristie, who is a Hungarian sufferer from Chiari Malformation Syndrome. She first became aware of the symptoms of the disease when she was 19 years old. Her channel on youtube seeks to help people suffering from other rare diseases as well as Chiari.

Marathon

D'Alonzo was and is a marathon runner, but, in the book, I could not help but imagine that the paperwork and time-wasting required to extract money from the health insurers, must have been the biggest, longest marathon. D'Alonzo is a highly restrained but nonetheless astute critic of the US profit-obsessed health system and cogently articulates the tragic farces it orchestrates. For instance, he is sent home after major neurosurgery, with a fever, urinary retention, and a bottle to urinate in, when he can hardly even look down to aim into the bottle, and absolutely no aftercare. That’s barbaric, and stupid as well, for many treatable, but potentially fatal complications happen shortly after operations. Recovery from operations on the neck, spine, brain and skull are complicated (to say the least) and patients need advice and rehabilitation.

”Many people with Chiari have significant mental and/or physical deficits following decompression surgery. One problem right off the bat that nearly all decompressed Chiarians share is the need to regain full range of motion in their necks. I am sure that many have had automobile accidents as a result of not regaining full range of motion in their necks. There are, of course, many other problems such as balance or gait problems, pain, vision problems, weakness, and the inability to concentrate or recall words to name just a few.” (p.144)

“My arms were a different matter. They were both weak and painful. The surgeon told me that my arms would feel better in about a year but provided no explanation as to why they were sore in the first place or instructions to aid in their rehabilitation.”(p.145)

D’Alonzo also criticizes the New Zealand health system, through the experiences of one Chiari Syndrome sufferer there who also had to wait years for a necessary operation, which was delayed four times. The New Zealand and the Australian health systems are purportedly free, but delays in the public system and hidden costs for unavoidable procedures and hospitalization in the private hospital benefits schemes mean that these antipodean systems are not all they are cracked up to be.

Misdiagnosis and Pharmacy in Chiari treatments

To deal with some bizarre, incapacitating symptoms, D'Alonzo is prescribed some major psychotropic drugs over the years. He is refreshingly sophisticated in his understanding of psychotropic and other drugs. He observes his own reactions, checks with the literature and draws logical conclusions.

It is thus educational to read of his experiences – well after his cervical decompression operation - coming off a 7.5mg daily dose of Zyprexa (Olanzapine) and then later, considering his height and weight (he is 6 feet 5 inches tall) what amounted to a tiny dose of 2.5mg daily.[1] He had problems with withdrawals and remarks on his experience ceasing the 2.5mg:

”It’s difficult to find any official or valid information on withdrawal side effects of Zyprexa. Some anecdotal accounts on the Internet can be found but many believe that there are no withdrawal side effects, just the return of symptoms from the underlying disease. This was not my experience. First, I had no ‘underlying disease’. As I indicated, I was not schizophrenic or depressed. Over the next two days, I experienced considerable GI distress, twitching, chills and sweats. My mood was down as would anyone’s be who was not feeling well but was not clinically depressed. I could still experience happiness and laugh at ordinary jokes and humor. Finally at about 8 days after I discontinued taking Zyprexa, I began to feel well again. All of the withdrawal symptoms faded away, my mood was excellent and I could actually sleep.”

A pharmaceutical reseacher (former Associate Director of Research and Development at Proctor and Gamble Pharamceuticals) his observations on the efficacy of medications, his ability to separate side-effects from the effects of Chiari Syndrome, including secondary effects, such as depression, and to admit when he doesn't know, is most instructive. He applies similar gifts of observation and analysis to the various health professionals who attempt to treat him.

We see most of these people as if they were dealing with him quickly, at arms length, in their offices, after he has waited weeks or months to see them. We recognise the humility and desperate self-control of the patient who simply must find medical help for a range of bizarre and refractory ailments.

Depression

If you experience difficult symptoms in the absence of known cause which stop you from leading a normal life, you are likely to become depressed. D'Alonzo, who has been for some time part of a Chiari Syndrome self-help group, finds that more Chiari Syndrome people are treated by psychiatrists - and for depression - than are treated by neurologists. (Then again there is the problem in neurology of higher status being accorded to brain surgeons than to clinicians who imaginatively support, assist, listen to and educate people away from the operating table.) The Chiari Syndrome often remains undiagnosed or untreated even if diagnosed, with the symptoms as physical consequences downplayed in favour of being reinterpreted as a depressed or obsessed reaction with something apparently minor to the apparently objective view.

"CMI is usually misdiagnosed as multiple sclerosis (MS), fibromyalgia (FM), chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) or clinical depression. Recent research by Dr. Dan S. Heffez suggests that as many as 20 to 25% of the 4 to 5 million patients in America diagnosed with FM/CFS have been misdiagnosed and actually have CMI."

D'Alonzo seems to waste literally years - and presumably enormous amounts of medical insurance and energy on psychiatrists. He is referred to them by ordinary doctors whom he initially consults for a strange sore throat which can finally probably be traced to pressure on the lower cranial nerves. One of his dominant problems becomes insomnia. These psychiatrists prescribe him anti-depressants and major tranquillizers in an effort to assist him to get sleep. And they try to find psychological causes. During one period he goes for eight days without sleeping, although this does not sound like mania.

Surgery

Surgery was put off for years even after a correct diagnosis was made. The reason was apparently confusion as to the importance of the amount of prolapse into the spinal canal of the brain. D'Alonzo's prolapse was judged not to be sufficiently profound. The basis of this judgement seems to have been a medical fashion, or poorly tested science. D'Alonzo tells us about this in detail.

Amazingly, after his successful surgical treatment one antidepressant appears to work on some severe recalcitrant symptoms. After his long-awaited decompression surgery, his insomnia and his preoccupation with it and the resurfacing of ancient long-forgotten resentments, were driving him closer and closer to suicide. Reluctantly he checked into a psychiatric facility which also had a sleep clinic. (It sounds like an unusually good facility).

The psychiatrist who treated him there thought that he had become obsessed with not sleeping and prescribed Anafranil (clomipramine) for the obsessive element of depression. D'Alonzo expected to be disappointed but began with a 50mg dose, working up to 100mg before leaving the hospital. The medication did not cure his insomnia, but it fixed some other longstanding distressing problems:

"That evening, I took a 50mg dose of Anafranil. It didn't make me drowsy and I did not sleep. However, in the morning, I had difficulty urinating. It was as if I had no need to urinate. This was good since I had been suffering so long from frequent urination. More important and to my surprise, I was no longer cold."

"Things were difficult for the next 6 weeks or so. I got very little sleep and didn't feel well. However, by fall, the Anafranil began to kick in. [Anafranil takes around 6 weeks to fulfill its potential.][4] The depression lifted and I began to sleep 4or 5 hours a night on a regular basis. The change in medication made all the difference in the world. I also found my tolerance for exercise was greatly increased..."

Far-reaching impact of medical arrogance

"I was on disability. I pretty much came to the conclusion that I would never feel well again. I was depressed and sometimes thought about suicide. The doctors were convinced that clinical depression was my problem and the cause of my physical symptoms. They had pretty much convinced my wife which really drove me into loneliness. When your spouse is forced into a state of confusion, you are truly alone." (p.177)

Those are telling, final words in Appendix 18 of the second edition. They convey mountains. For me they conjure up the undeserved lot of so many patients I have met.

Chiari in the European medical and hospital system

In France, if you look up le syndrome de Chiari you immediately find that there is a big hospital - Bicetre Hosp in Paris, with a department, le Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Bicêtre, concerned with treating its effects. This is the Referral center for Rare Diseases, which holds a 5 year renewable government licence for that specialty. I would be interested to hear more about treatment in Europe.

Psychiatry and Rare Diseases

What's the connection?

I work in the psychiatric field. In psychiatry the risk of seeing rare diseases is very high, although we don't always recognise them.[2] Because I like to help people and I enjoy solving mysteries, I try to familiarise myself with rare diseases, particularly those that have neurological causes.

Why is the risk so high? It is high because persistent symptoms with no recogniseable cause can look like forms of neurosis or psychosis. People who continue to complain of such symptoms or whose behaviour changes because of those symptoms tend to get shuffled along the hospital production line all the way to psychiatry, which, for many, is a dead end. Often it is worse than a dead end, with the prescription of powerful, but not very helpful, psychiatric drugs, with awful side-effects, like unbelievable obesity, continuous restlessness, or the living grave of drug-induced Parkinsonian syndromes. For the person suffering the symptoms, with or without inappropriate treatment, the experience can obviously be be an ongoing nightmare, with suicide sometimes a reasonable option.

If your symptoms are odd neurological ones that wax and wane without an obvious pattern, your chances of being described as having unreasonable concerns are high. If, through your 'unreasonable concerns' you perseveratively seek medical help, lose control of your emotions or limbs, lose your job, home, family, come to the attention of the police, you are likely to be judged psychiatrically incompetent in some way and there will be attempts to treat you. To treat you the system, public or private (if you are insured) will demand some kind of psychiatric diagnosis. Medical diagnosis is rarely an 'exact science' and in psychiatry even less so. The English-speaking Western world's principal diagnostic criteria is based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association. This constantly redecorated creaking 19th century edifice, whilst it inspires awe in those who gaze at it from afar, recently prompted a Professor of Theoretical Medicine, Bruce Charlton, to call it a "a terrible, misleading mess." [3]

In all fields of medicine, including psychiatry, as in every field of life, the majority of people you meet prefer life to be predictable. They are put out by patients who don't fit into preconceived moulds. There are however always exceptions to this rule, in the people who enjoy the unpredictable and rise to a challenge. There is a place for mavericks.

US Medical and Pharmaceutical System

The following is my opinion, not that of Raphael D'Alonzo.

The United States of America is a place where everyone (except the rich) is expected to work much harder than in most other countries. This political situation is promoted as "freedom" to strive for wealth. The protestant religious system can be made to fit the idea that anyone not thriving in such a system does not deserve to. Medical insurance depends on employment if you don't have an independent fortune. Should you fall ill and be unable to work, your chances of decent survival - or even of survival - decrease rapidly. As Michael Moore's movie, Sicko showed, even if you are employed and have medical insurance, the US private insurance system is so corrupt that it can fail to render necessary assistance to paid-up subscribers whose lives are endangered by their illness, and leave them to die or be crippled. The same film also showed that the public hospital system was similarly corrupt, as it dumped the uninsured on the street. The medical system of North America's old bête noir, Cuba, was held up effectively to put the US to shame.

The US medical system is an argument in itself for socialised medicine. It is wealthy, costly, clumsy, inadequate and corrupt, like the worst of despots.

If the United States were really a democracy, this system would be dismantled and its champions hauled into court, but in the US democracy is only another brand-name, over-used to sell sanitised corporate military invasions of countries which have something that big investors want. Forces in Australia have set the system there drifting off-course towards the same dog-eat-dog situation.

The pharma of big capitalism depends on economically critical masses of disease sufferers and financial injections. If it doesn't get these, even if there is a potential or actual cure, it will not be developed or made available to sufferers.

At least the internet offers a form of relocalisation according to shared causes, which permits an electronic banding together to seek solutions for specific problems.

We live in hope.

Resources for Chiari sufferers and those interested

Conquer chiari or chiari & Syringomyelia Patient Education Foundation

World Arnold Chiari Malformation Association

American Syringomyelia Alliance Project or ASAP

The Chiari Institute

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

University of Washington Chiari Malformation Clinic

Referral center for Rare Diseases, Bicetre Hospital, Paris, France

Chiaria and Syringomyelia Australia

Notes

[1] Psychiatric patients are frequently medicated with 10, 20, 30 and even 40 and 50mg Zyprexa. Imagine what they go through.

[2]I've been in the sector for years and I think that I can speak from experience backed by wide reading. Feel free to take issue with any of my observations and arguments. The health field, not just the psychiatry field, needs to be much more open to unmediated questions from the public. Lively as well as serious debate is desirable.

[3] Bruce Charlton, in chapter three of his book, Psychiatry and the Human condition,available on-line or from Radcliffe Medical Press, Oxford, UK, 2000. More fully, he explains, "These diagnostic systems employ a syndromal system of classification that derives ultimately from the work of the psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin about a hundred years ago, and is therefore termed the ‘neo-Kraeplinian’ nosology. Whether or not a psychiatrist uses the formal diagnostic criteria, the neo-Kraeplinian nosology has now become ossified in the DSM and ICD manuals. Over the past few decades the mass of published commentary and research based on this nosology has created a climate of opinion to challenge which is seen as not so much mistaken as absurd."]

[4] Bruce Charlton (see above) theorises that antidepressants are actually another form of pain-killer.

Grassroots advocacy group, Australians for Mental Health (AfMH) is calling for urgent and significant reform following a damning assessment found the national plan to improve mental health and prevent suicide is “not fit for purpose.”

Grassroots advocacy group, Australians for Mental Health (AfMH) is calling for urgent and significant reform following a damning assessment found the national plan to improve mental health and prevent suicide is “not fit for purpose.”

Wednesday, 10 April 2019: A study published in

Wednesday, 10 April 2019: A study published in

Click for larger image. The illustration is a detail from Dulle Meg or Dulle Griet by Pieter Breughel. It means "Mad Meg" and actually illustrates a woman who leads an army of women to pillage Hell. The woman's dress is reminiscent of one eccentric way some people with schizophrenia dress in order to protect themselves from enigmatic threats, invisible to others. (Explanation and choice of illustration by Sheila Newman.)

Click for larger image. The illustration is a detail from Dulle Meg or Dulle Griet by Pieter Breughel. It means "Mad Meg" and actually illustrates a woman who leads an army of women to pillage Hell. The woman's dress is reminiscent of one eccentric way some people with schizophrenia dress in order to protect themselves from enigmatic threats, invisible to others. (Explanation and choice of illustration by Sheila Newman.) The Australian College of Mental Health Nurses (ACMHN) joins the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists’ (RANZCP) in condemning the recent announcement by Queensland Health to introduce ‘lock-up’ security measures to all adult mental health hospital inpatient facilities in Queensland, and the expansion of the use of ankle bracelets.

The Australian College of Mental Health Nurses (ACMHN) joins the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists’ (RANZCP) in condemning the recent announcement by Queensland Health to introduce ‘lock-up’ security measures to all adult mental health hospital inpatient facilities in Queensland, and the expansion of the use of ankle bracelets. This week, Queensland Health ordered the State’s 16 mental health inpatient facilities to be secured, and a new ‘locked-door’ policy to be adopted effective 15 December 2013.

This week, Queensland Health ordered the State’s 16 mental health inpatient facilities to be secured, and a new ‘locked-door’ policy to be adopted effective 15 December 2013. Author and Chiari Syndrome sufferer, Rahael D'Alonzo, has written a fascinating personal account and investigation of this obscure, chameleon and pervasive syndrome, which often requires neurosurgery and may be life-threatening. His style is direct, his observations detailed and scientific, his accounts of human mismanagement of his diagnosis and treatment revealing but fair. His perspective is both useful and unusual because of his own background as a pharmaceutical research scientist and his strong personality and physical stamina. He has a sophisticated understanding of the United States health insurance industry.

Author and Chiari Syndrome sufferer, Rahael D'Alonzo, has written a fascinating personal account and investigation of this obscure, chameleon and pervasive syndrome, which often requires neurosurgery and may be life-threatening. His style is direct, his observations detailed and scientific, his accounts of human mismanagement of his diagnosis and treatment revealing but fair. His perspective is both useful and unusual because of his own background as a pharmaceutical research scientist and his strong personality and physical stamina. He has a sophisticated understanding of the United States health insurance industry.

Recent comments