Court Decision: Rainbow Shores P/L v Gympie Regional Council & Ors: The proposal (i) would adversely impact on the flora, fauna and biodiversity values to an unwarranted extent; (ii) would consequently conflict with the provisions of various planning documents, including the superseded, existing and draft planning schemes; and (iii) is not supported by sufficient economic, community or planning need; and (e) the matters relied upon by the appellant are not sufficient to warrant approval otherwise. The appellant has not discharged its onus. The appeal is dismissed. (Transcript of decision inside.)

Court Decision: Rainbow Shores P/L v Gympie Regional Council & Ors: The proposal (i) would adversely impact on the flora, fauna and biodiversity values to an unwarranted extent; (ii) would consequently conflict with the provisions of various planning documents, including the superseded, existing and draft planning schemes; and (iii) is not supported by sufficient economic, community or planning need; and (e) the matters relied upon by the appellant are not sufficient to warrant approval otherwise. The appellant has not discharged its onus. The appeal is dismissed. (Transcript of decision inside.)

Candobetter editors learned tonight that Greg Wood (who we know) and others we have not met, who have fought for over six years against professional defenders of development: raising funds, attending and defending in court, hiring experts, publishing newspapers, running in local elections - whilst employed full-time just earning their own livings, have finally won this case. To them we say, Bravo! Thankyou. An incredible battle! An amazing result. A rare and magnificent environment and justice win in Queensland today.

Candobetter editors learned tonight that Greg Wood (who we know) and others we have not met, who have fought for over six years against professional defenders of development: raising funds, attending and defending in court, hiring experts, publishing newspapers, running in local elections - whilst employed full-time just earning their own livings, have finally won this case. To them we say, Bravo! Thankyou. An incredible battle! An amazing result. A rare and magnificent environment and justice win in Queensland today.

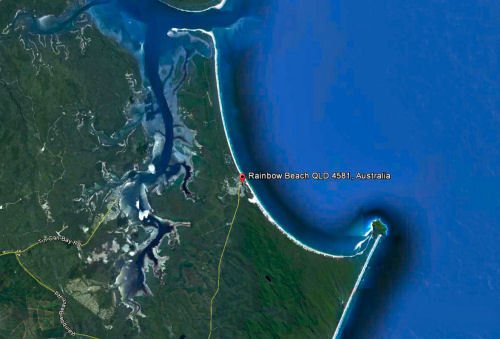

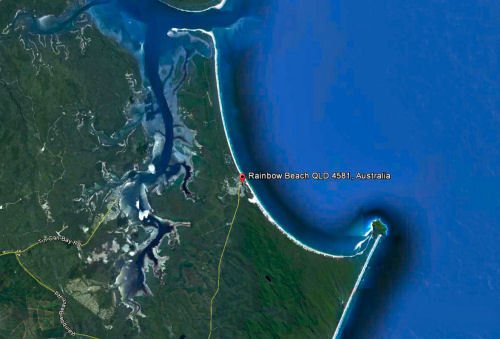

Just a short swim away from Fraser Island, Rainbow Beach, on the Cooloola Coast Queensland, is the last remaining expanse of natural open space and intact environment left within coastal mainland S.E. Queensland. Its social and ecological value is incalculable in monetary terms due to its now extreme rarity. Animals and plants of many species that have disappeared in other parts of Queensland, still survive here, precisely because it has not been fragmented by development and overpopulation. Natural features in the area are also unique and of global significance.

Due to this court decision, free of high density development, Rainbow Beach will continue to provide a true refuge from the ever accelerating growth and commercial take-over of the rest of Queensland, as it is sold off at bargain-basement prices and destroyed in the process. People value the tranquility of Rainbow Beach and do not want this ruined by urban expansion, which incidentally also destroys the long-term value of their homes. This win in court is a great win for Queensland at a time when Queensland is under ever increasing attack from its own government.

The Court decision is attached as a pdf file and cut and pasted below as a text document as well. We apologise for the lack of attention to setting out in the text document, which we are keen to make available as soon as possible.

The Rainbow Beach site created to defend this area is at www.saveinskip.org.au

The Decision

[For the pdf version click here

[Text document requires further lay-out editing which cannot be done immediately]

PLANNING & ENVIRONMENT COURT OF QUEENSLAND CITATION:

Rainbow Shores P/L v Gympie Regional Council & Ors [2013] QPEC 26 PARTIES:

RAINBOW SHORES PTY LTD (Appellant)

V GYMPIE REGIONAL COUNCIL (Respondent)

And CHIEF EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND RESOURCE MANAGEMENT (Co-respondent)

And J. LAWLER & ORS (First respondent by election)

And FRASER ISLAND DEFENDERS ORGANISATION LIMITED (Second respondent by election)

And RAINBOW BEACH COMMERCE AND TOURISM ASSOCIATION INC (Third respondent by election)

And GREGORY DAVID WOOD (Fourth respondent by election)

And FIONA HAWTHORNE (Fifth respondent by election)

And VIVIEN GRIFFIN (Sixth respondent by election)

And NATIONAL PARKS ASSOCIATION OF QUEENSLAND

2 (Seventh respondent by election)

And COOLOOLA COAST CARE ASSOCIATION INC (Eighth respondent by election)

And CHIEF EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT OF MAIN ROADS (Ninth respondent by election)

FILE NO:

2768 of 2009 PROCEEDING:

Appeal ORIGINATING COURT:

Planning and Environment Court, Brisbane DELIVERED ON:

12 June 2013 DELIVERED AT:

Brisbane HEARING pection on the 12 and 13 December 2011 Trial on the 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 23, 24, 25, 27, 30, 31 January;

1, 2, 3, 27, 28 February; 21, 22, 23, 25, 28, 29, 30, 31 May; 1,

4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 13, 14, 15 June 2012 Submissions on the 11, 12, 13, 16 July 2012 Further written submissions received November 2012 Further oral submissions heard 27 November 2012 Further material and written submissions received to 14 February 2013 Further hearing on 28 March 2013 Further exhibits and written submissions received to 8 June

2013 JUDGE:

Rackemann DCJ ORDER:

The appeal is dismissed CATCHWORDS:

LOCAL GOVERNMENT– TOWN PLANNING – Development Application for preliminary approval for an integrated resort/commercial village within a broader residential community offering a range of housing styles and densities supported by retail, business services and community infrastructure and within vegetated community open space – application under Transitional Planning Scheme – weight to be afforded to existing planning scheme and draft planning scheme – Wide Bay Burnett Regional Plan – State Coastal Management Plan 2001 – Queensland Coastal Plan 2012 – Draft Coastal Plan State Planning Regulatory Provision 2012 – Coastal Plan State Planning Regulatory

3 Provision 2013, Temporary State Planning Policy 2/12 – Draft State Planning Policy – whether amendments to draft planning scheme colourable – need, economic, community and social benefit – weight attributed to a failure to demonstrate sufficient need – impacts on fauna, flora and biodiversity – importance of site to geological sciences – exposure of the site to erosion, storm surge and climate change related sea level rise – bushfire management – wastewater reuse and groundwater – impact of proposal on beach access – sufficiency of planning grounds or grounds to warrant approval – whether proposal to dispose of effluent for the ?whole of the community?, in addition to those on the subject site, an extraneous consideration.

COUNSEL:

Mr G Gibson QC with Mr J Houston for the appellant Mr S Ure for the respondent Mr D Gore QC with Mr M Williamson for the co-respondent Mr Lawler as agent for the first respondent by election Mr Elms as agent for the third respondent by election Mr Wood in person and as agent for the fifth to eighth respondents by election SOLICITORS:

Herbert Geer for the appellant King & Co for the respondent Crown Law for the co-respondent

4 Introduction.......................................................................................................................... 5 The issues............................................................................................................................. 6 The site................................................................................................................................. 7 History and background.......................................................................................................8 The role of the co-respondent............................................................................................. 10 The assessment and decision making regime ..................................................................... 11 The plan of development.................................................................................................... 16 The Statutory Planning Documents.................................................................................... 19 Documents in force when the application was made ......................................................... 20

1997 Transitional Planning Scheme................................................................................... 20 The State Coastal Management Plan (August 2001) .......................................................... 27 Subsequent statutory planning documents .........................................................................29

2005 IPA Planning Scheme................................................................................................ 29 Wide Bay Burnett Regional Plan....................................................................................... 34 Draft Gympie Regional Council Planning Scheme ............................................................ 36 Coastal Planning................................................................................................................. 43 Temporary State Planning Policy 2/12 – Planning for Prosperity ..................................... 52 Draft SPP............................................................................................................................ 55 Summary of planning documents....................................................................................... 60 Need and benefit................................................................................................................. 61 Need for tourist facilities.................................................................................................... 64 Need to accommodate residents......................................................................................... 71 Economic, community and social benefit ..........................................................................77 The weight to be attributed to the failure to demonstrate a sufficient public or community need.................................................................................................................................... 80 Fauna, flora and biodiversity.............................................................................................. 83 Landscape Character and Natural Amenity ...................................................................... 105 Geology and Geomorphology.......................................................................................... 106 Erosion.............................................................................................................................. 112 Storm surge/climate change/sea level rise ........................................................................114 Consequences of erosion and storm surge issues ............................................................. 116 Wastewater reuse and groundwater.................................................................................. 117 Access to the beach..........................................................................................................122 Bushfire management.......................................................................................................123 Sufficient planning grounds or grounds ...........................................................................124 Conclusion........................................................................................................................ 133 Annexures......................................................................................................................... 135

5 Introduction

[1] This appeal concerns the proposed future development of a relatively large integrated resort and residential community within the attractive, but modestly developed, locality of Rainbow Beach and Inskip Peninsula on the Cooloola Coast.

The proposal envisages extensive development on a large site on the eastern (beach) side of Inskip Peninsula, which lies to the north of the current town centre of Rainbow Beach and to the South of Fraser Island, to which there is access by vessel from Inskip Point.

[2] Rainbow Beach has its own very attractive beach and lies in close proximity to places and features of great natural beauty, interest and attraction. Existing development for both residents and tourists is modest, although there are substantial camping areas at Inskip Point. The existing permanent resident population of Rainbow Beach is approximately only 1,000. Tourist numbers swell during holiday times when up to 3,000 campers descend upon Inskip Point. The subject proposal envisages faster growth and greater development in the future, resulting in a maximum population (tourists and residents) on the subject site alone of up to 6,550 persons.

[3] The appellant is the disappointed applicant for a preliminary approval for a material change of use for an ?integrated resort/commercial village within a broader residential community offering a range of housing styles and densities supported by retail, business services and community infrastructure set within vegetated community open space?. That development is proposed to be governed by a plan of development.

[4] The application was refused by the respondent, at the direction of the co-respondent, on the basis of perceived environmental impact. The respondent did not call any evidence at the hearing and ultimately submitted that the appeal ought to be allowed and the application approved. It was surprising that, in a case where conformity or otherwise with the Council‘s planning documents was in issue, and where the Council had been represented throughout the lengthy hearing, no substantive submission was made, on the Council‘s behalf, about the planning documents, save for an erroneous (and later withdrawn) submission concerning an irrelevant provision of the 1997 Planning Scheme and submissions about the weight to be placed on the Council‘s new draft planning scheme and amendments thereof (discussed later). Refusal of the application was vigorously advocated by the co-respondent.

[5] The development application generated much interest and a large number of submissions, both for and against. Some of those submitters elected to become parties to the appeal. The third respondent by election supports the proposal, chiefly because of the perceived economic advantages of the substantial development contemplated by the proposal, should it come to fruition. The first and fourth to eighth respondents by election oppose the appeal on a number of grounds.

The second respondent by election withdrew. The ninth respondent by election took no active part in the hearing, as the traffic issues were resolved (subject to the imposition of conditions on any approval) prior to trial.

The issues [6] The issues in dispute were the subject of notification, particularisation and supplementation over an extended period. Copies of the relevant correspondence and other documents filled a volume, which became exhibit 4. Mercifully, in the course of the hearing, the parties produced a relatively brief list of agreed issues1.

The issues pursued at the hearing2 may be summarised as relating to:

- Town planning

- Need and benefit

- Flora, fauna and biodiversity

- Landscape character and natural amenity

- Geology and geomorphology

- Coastal processes, erosion and storm surge

- Waste water reuse and ground water

- Beach access

1 See exhibits 68, 68A, 142 and 142A.

2 Water supply issues were dropped by Mr Lawler following completion of the evidence.

- Bushfire management

- Sufficiency of grounds or planning grounds to warrant approval The site [7]

The land the subject of the development application, which is referred to as Rainbow Shores Stage 2 (RS2):

(a) is located at Inskip Avenue, Rainbow Beach, on the Inskip Peninsula north of the established town centre;

(b)is more particularly described as Lot 22 on Plan MCH803497;

(c) contains an area of approximately 200 hectares;

(d) is rectilinear in shape, with a long western frontage, of approximately 4.5 kilometres, to Inskip Avenue;

(e) is bounded to the east (beachside) by unallocated State land which provides a beach protection area between the subject site and the beach proper;

(f) is largely covered by vegetation which has achieved remnant status;

(g) provides habitat for important flora and fauna species;

(h) was subject to earlier sand mining and disturbance around the mined areas over a total of approximately 14% of its area; and

(i) is part of a larger area held by the appellant under a development lease granted for business, residential, tourism and recreational purposes, entered into with the State of Queensland in November 1984 (=the development lease‘). That lease is due to expire next year. The development assumes that the appellant will ultimately be successful in obtaining an extension or renewal of the lease.[8]

Part of the area under the development lease is in the process of being developed as a ?residential community comprising units, dwellings, retail and commercial establishments with a maximum resident population of 4,100 persons?. This area, which lies approximately 1.5 kilometres to the south of the subject site, is known as Rainbow Shores Stage 1 (=RS1‘). The RS2 site is separated from the RS1 site by Lot 24 on MCH5478 (referred to as the ?green belt?) which is unallocated State land and contains an area of about 53.6 hectares3. The locations of RS1 and RS2 appear on annexure 1 to these reasons.

3 Exhibit 7, tab 3.

History and background [9]

The appellant‘s pursuit of development under the development lease and of the subject development application has a long and somewhat tortured history. The site (together with other parts of Inskip Peninsula) was once sand mined. Those activities ceased in the 1970s. It would appear that the development lease was granted in the context of the relinquishment of sand mining rights.[10]

In 1987, Mr and Mrs Krauchi acquired the shares in the appellant company, with a view to exercising the rights under the development lease. The Krauchi family has controlled the appellant ever since. In 1989 the area covered by the development lease was varied so as to create the two separate sites known as RS1 and RS2, separated by the green belt that was transferred to the Crown.[11]

In 1989 an application was made to rezone the RS1 site. That was successful, with the rezoning being gazetted in 1991. Various plans of subdivision were subsequently registered and the development of RS1 commenced, although it is still far from complete, some 20 years later.[12]

The residential development in RS1 features 35 metre wide ?green fingers? of retained vegetation which separate the backyards of detached houses facing one street from the backyards of those facing the next. The extent of tree retention more generally within RS1 is uncommonly high by the standards of typical suburban subdivisions. It was said that this provides an illustration of what is contemplated within RS2.[13]

Planning for the development of the much larger RS2 site commenced in 1992 with the submission of an overall design plan to the Land Administration Commission.

It was not until 1999 however, that a pre-application report was submitted to the Council and to the Department of Natural Resources (=DNR‘).[14]

In 2000 the DNR was requested to provide ?owners consent? to permit the appellant to make its development application over RS2. The DNR delayed in doing so. It first wished to examine various merit-based issues in relation to the substance of the application. Ultimately it took some four years for the appellant to secure the consent which it needed before it could lodge its development application. The development application was lodged on 11 August 2004. It was met with an extensive information request which was not responded to until 2006. In the course of discussions, the referral agency assessment period was ultimately extended until August 2009.[15]

In early 2007 the State approached the appellant to open negotiations for a 'land swap' which would have seen the appellant develop other land instead of the RS2 site. Negotiations proceeded for some two years until, in 2009, the appellant was informed that the State no longer wished to proceed with a land swap. In the same year, the co-respondent, as a concurrence agency for the development application, directed the Council to refuse the development application for the RS2 site. It has resisted the subsequent appeal on bases which, if accepted, would mean the RS2 site has, at best, more modest development potential, given its environmental values.[16]

The co-respondent has been vigorous in its opposition to the proposal. It also provided public funding to some of those co-respondents by election who are opposed to the development, so that they could engage experts in the fields of town planning and economics.[17]

In the circumstances one might be forgiven for having a degree of sympathy for the appellant. The State was content to grant a development lease in the context of the relinquishment of mining rights. It was content for development to proceed on RS1.

Subsequent attempts by the appellant to pursue an application for similar development (albeit on a larger scale) on the RS2 site were, however, delayed for four years (before 'owners consent' was given to the making of the application) before being refused at the direction of the co-respondent. The State, through the co-

respondent, now asserts that RS2 has environmental values which at least significantly diminish its development potential. It so contends notwithstanding that, with the demise of the mooted ?land swap? proposal, the appellant would be left with no 'in kind' compensation.

10 [18] Ultimately however, the decision in this matter cannot be driven by notions of sympathy. Rather, it must be the result of a dispassionate assessment of the relevant considerations. Further, as was submitted on behalf of the co-respondent:

(a) The development lease is not a town planning document;

(b) The development lease put the onus upon the appellant to obtain the necessary town planning approvals;

(c) The decision to grant the development lease cannot validly fetter statutory planning discretions conferred under separate legislation; and

(d) There is no relevant coincidence of identity, function or time in respect of the grant of the development lease and the direction to refuse the development application. The development lease was granted by the Governor-in-Council in the exercise of a legislative authority to deal with the occupation of Crown land, while the direction to refuse development was made by the Chief Executive of a Department pursuant to separate statutory powers.

The role of the co-respondent [19] The development application was referred to the Environmental Protection Agency (which was subsequently absorbed into the co-respondent) as a concurrence agency.

The referral jurisdiction was described in the relevant regulation as:

'Coastal management, other than amenity and aesthetic significance or value.'[20]

In the course of the hearing the co-respondent relied on a range of issues including matters made relevant by the statutory town planning documents. The connection between such matters and the co-respondent‘s referral jurisdiction is perhaps not immediately obvious. As was pointed out for the co-respondent however, =coastal management‘ is a term of wide import and s 3.3.15 of the Integrated Planning Act 1997 (=IPA‘), in stating how, at the relevant time, a referral agency was to assess an application, provided, in part as follows:

"(1)

Each referral agency must, within the limits of its jurisdiction, assess the application—

(a) against the laws that are administered by, and the policies that are reasonably identifiable as policies applied by, the referral agency; and

(b) having regard to—

(i) any planning scheme in force, when the application was made, for the planning scheme area; and

(ii) any State planning policies not identified in the planning scheme as being appropriately reflected in the planning scheme; and

(iii) if the land to which the application relates is designated land— its designation; and

(c) for a concurrence agency—against any applicable concurrence agency code. ..." [21]

Section 3.3.15 therefore obliges a concurrence agency, such as the co-respondent, to assess the development application within the limits of its jurisdiction, but having regard to the planning scheme and State planning policies. Having directed Council‘s refusal of the development application, the concurrence agency became a co-respondent for the appeal, with an entitlement to be heard as a party.

The assessment and decision making regime [22] The development application was made during the currency of the IPA. For the purposes of the development application, provisions of the IPA continue to apply as if the Sustainable Planning Act 2009 (=SPA‘) had not commenced5.

[23] There are two aspects of the development application before the court, namely:

(a)

A development application for preliminary approval for material change of use; and (b)

A request to vary the effect of a local planning instrument for the land.

[24] The development application for the preliminary approval for material change of use was made during the currency of the Council‘s now superseded 1997 Transitional Planning Scheme. For the purposes of that planning scheme, the land was included in the Rural Zone where commercial premises, hotel, multi-unit accommodation, shop and shopping centre were prohibited development. In the old terminology, a rezoning would have been required for the material change of use

4 Integrated Planning Act 1997 (Qld) s 3.3.15 in force on the DA submission date of 11 August 2004.

12 aspect. As the application would have required a rezoning under the repealed Act6 (=PEA‘)7 and, in turn, would have required public notification, the application was to be processed as if it were an application requiring impact assessment8.

[25] The application for the preliminary approval for a material change of use is to be assessed pursuant to s 6.1.29 of the IPA which relevantly provides, in part:

?6.1.29 Assessing applications (other than against the Standard Building Regulation)

(1)

This section applies only for the part of the assessing aspects of development applications to which a transitional planning scheme or interim development control provision applies.

(2)

Sections 3.5.4 and 3.5.5 do not apply for assessing the application.

(3)

Instead, the following matters, to the extent the matters are relevant to the application, apply for assessing the application— (a)

the common material for the application; (b)

the transitional planning scheme; ...

(e)

all State planning policies; (f)

the matters stated in section 8.2(1) of the repealed Act; ...

(h)

if the application is for development that before the commencement of this section would have required an application to be made under any of the following sections of the repealed Act— (i)

section 4.3(1)—the matters stated in section 4.4(3); … (i)

any other matter to which regard would have been given if the application had been made under the repealed Act?9.

[26] Section 8.2(1) of the PEA provided as follows:

5 Sustainable Planning Act 2009 (Qld) s 802(2).

6 The Local Government (Planning and Environment) Act 1990 (Qld).

7 See The Local Government (Planning and Environment) Act 1990 (Qld) s 4.3(1).

8 IPA s 6.1.28(2)(a).

9 IPA s 6.1.29.

13 ?8.2 (1) Without derogating from any of its powers under this Act or any other Act, a local government, when considering an application for its approval, consent, permission or authority for the implementation of a proposal under this Act or any other Act, is to take into consideration whether any deleterious effect on the environment would be occasioned by the implementation of the proposal, the subject of the application.?

[27] The matters stated in s 4.4(3) of the PEA were as follows:

?4.4(3) In considering an application to amend a planning scheme or the conditions attached to an amendment of a planning scheme a local government is to assess each of the following matters to the extent they are relevant to the application— (a)

whether the proposal, if approved, or buildings erected in conformity with the proposal, or both the proposal, if approved, and the buildings so erected would— (i)

create a traffic problem, increase an existing traffic problem or detrimentally affect the efficiency of the existing road network; (ii)

detrimentally affect the amenity of the neighbourhood; (iii) create a need for increased facilities; (b)

the balance of zones in the planning scheme area as a whole or that part of that area within which the relevant land is situated and the need for the proposed planning scheme amendment; (d)

whether the land or any part thereof is so low-lying or so subject to inundation as to be unsuitable for use for all or any of the uses permitted or permissible in the zone in which the land is proposed to be included; (e)

whether, having regard to the permitted or permissible uses of the land and the potential for subdivision in the zone in which it is proposed to be included water, gas, electricity, sewerage and other essential services should be made available to the land and to each separate allotment thereof if the land were subsequently subdivided; (f)

the impact of the proposal on the environment (whether or not an environmental impact statement has been prepared); (g)

the situation, suitability and amenity of the land in relation to neighbouring localities; (i)

the advice given by it, in respect of any consideration in principle concerning the relevant land pursuant to section 4.2; (j)

whether any plan of development attaching to the application pursuant to a requirement of the planning scheme should be altered; (k)

where the land is land prescribed pursuant to section 8.3A, the site contamination report in respect of the land; (l)

such other matters, having regard to the nature of the application, as are relevant.?

14 [28] The 1997 Planning Scheme included a list of matters to be taken into account, to the extent they are relevant to the application. Those included10:

?? 6 when considering an application to amend the scheme, whether there is a need for the proposal ? 11 the extent to which the proposal is affected by State Planning Policies ? 12 the impact of the proposal on the environment …?

[29] The application for the material change of use is decided pursuant to s 6.1.30 of the IPA which relevantly provides:

“6.1.30 Deciding applications (other than against the Standard Building Regulation)

(1)

This section applies only for the part of the deciding aspects of a development application to which a transitional planning scheme or interim development control provision applies.

(2)

Sections 3.5.13 and 3.5.14 do not apply for deciding the application.

(3)

Instead, the assessment manager must, if the application is for development that before the commencement of this section would have required an application to be made under any of the following sections of the repealed Act— (a)

section 4.3(1)—decide the application under section 4.4(5) and (5A); ……?

[30] Sections 4.4(5) and 4.4(5A) of the PEA provided as follows:

?4.4(5) In deciding an application made to it pursuant to section 4.3 a local government is to— (a)

approve the application; or (b)

approve the application, subject to conditions; or (c)

refuse to approve the application.?

?4.4(5A) The local government must refuse to approve the application if— (a)

the application conflicts with any relevant strategic plan or development control plan; and (b)

there are not sufficient planning grounds to justify approving the application despite the conflict.?

10 Cooloola Shire Council Planning Scheme 1997 s 15.10.6.

15 [31] With respect to s 4.4(5A) of the PEA, White J (as she then was) observed in Grosser v Council of the City of Gold Coast11:

?Section 4.4(5A) is a simple two-stage process which first requires the identification of conflict with the Strategic Plan, then, if conflict is present, the application must be refused if there are not sufficient planning grounds to justify approving the application despite the conflict.?

[32] That aspect of the application seeking to vary the effect of a local planning instrument is to be assessed having regard to s 3.5.5A of the IPA12.

[33] That aspect of the application seeking to vary the effect of a local planning instrument is decided having regard to s 3.5.14A of the IPA which provided, in part, that:

?(1) In deciding the part of an application for a preliminary approval mentioned in section 3.1.6 that states the way in which the applicant seeks the approval to vary the effect of any applicable local planning instrument for the land, the assessment manager must— (a)

approve all or some of the variations sought; or (b)

subject to section 3.1.6(3) and (5)—approve different variations from those sought; or (c)

refuse the variations sought.

(2)

….?

[34] The appeal to this court proceeds as a hearing anew of the merits of the development application. The court must decide the appeal based on the laws and policies applying when the development application was made, but may give weight to any new laws and policies the court considers appropriate13. The appellant bears the onus.

11 [2002] QPELR 207 at [49].

12 That section was inserted in the Integrated Planning and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2003 (No. 64), which was assented to on 16 October 2003, but relevantly did not commence until 4 October 2004. The subject application was made within that period, in August 2004. Section 3.5.5A of IPA is relevantly prospective in operation, in a case such as the present.

13 Integrated Planning Act 1997 (Qld) s 4.1.52.

16 The plan of development [35] The proposed development of RS2 would be governed by a Plan of Development (POD), which would vary the effect of the planning scheme. The proposed POD sets out the approval framework that would apply to the RS2 development. Future applications for development permits would be assessed against the POD. The POD includes provisions dealing with levels of assessment and a series of codes.

[36] The POD seeks to achieve ?triple bottom line? development, which it describes as follows:

?

?The development will incorporate state of the art ESD principles and systems, designed to preserve and enhance the natural assets of the site, particularly the sensitive foreshore dune ecology; ?

The development will incorporate new urbanist town planning principles adapted to the site‘s Queensland coastal context: principles that promote pedestrian permeability over reliance on cars; access to dedicated open space corridors; and the provision of amenities that encourage social interaction amongst visitors and residents. The town centre and resort will be designed to enhance the sense of community; and ?

The development will provide a balance of opportunities for permanent residents and short term holiday accommodation, with the inclusion of commercial, recreational and institutional facilities required for an economically sustainable community. Jobs created from the tourist related components of the resort development and ancillary services are expected to offer a major boost to the local economy.?

[37] The overall outcomes for RS2 are said to be:

?

?The location, extent and mix of development, including open space, is generally in accordance with the Plan of Development Precinct Plan; ?

The location and nature of roads are generally in accordance with Plan of Development Indicative Vehicle Access Plan; ?

The location and nature of pedestrian and bike access ways are generally in accordance with the Plan of Development Indicative Pedestrian Access Plan.

?

Rainbow Shores Stage 2 planning area will accommodate up to a maximum population of 6,550 persons.

?

The amenity of the Rainbow Shores Stage 2 planning area is maintained providing an attractive place to live, work and visit.

?

Development is undertaken having regard to significant environmental areas.

?

Natural coastal processes continue to occur with minimal interference from development; and

17 ?

Buildings and structures in the Rainbow Shores Stage 2 utilised materials and forms appropriate to the surrounding natural setting.?

[38] The Plan of Development Precinct Plan divides the site into four precincts as well as a number of sub-precincts as follows:

(a)

Housing precinct – which is to accommodate up to 4,900 persons in a range of housing styles and at variety of densities across four sub-precincts as follows:

H1 – sub-precinct 1 – providing single detached houses on lots of 450 m2 to

1250 m2.

H2 – sub-precinct 2 – providing attached housing comprising duplex dwellings and townhouses.

H3 – sub-precinct 3 – providing low density resort style bungalows.

H4 – sub-precinct 4 – providing high density apartments.

Sub-precincts H3 and H4 are also intended to accommodate low key small scale commercial entertainment and convenience retail uses.

(b)

Resort Precinct – which is to accommodate up to 1,122 persons in resort style accommodation together with up to 1,500 m2 of retail and commercial space.

(c)

Mixed Use Precinct – which is to accommodate a maximum of approximately

5,500 m2 of retail and commercial space together with accommodation for 330 persons.

(d)

Community precinct – C1 – sub-precinct 1 – providing for community facilities.

C2 – sub-precinct 2 – providing community open space.

The various precincts and sub-precincts are shown on the Plan of Development Precinct Plan, a copy of which is Annexure 2 to these reasons. The overall future development pattern, across the site, is shown indicatively on the ?Indicative Land Use Plan? a copy of which is Annexure 3 to these reasons14.

[39] Figures 2-4 and 2-5 in the POD, copies of which are annexures 2 and 3 to these reasons, are plans for ?standard lot development? for dwelling houses and multi-

residential developments respectively. They show the incorporation of ?green

18 fingers? of retained vegetation, similar to those provided in RS1. At 25 m wide, they are narrower than provided in RS1, but reliance is placed upon controls on clearing in the adjoining backyards of developed lots. These ?green fingers? are relevant to the appellant‘s case on the environmental issues, discussed later.

[40] It is intended, as a first step towards realising development, that a Master Population Distribution Plan (MPDP) would be prepared and submitted as part of an application for another preliminary approval affecting the whole of the site. This would show how the intended maximum population is to be distributed across the site, between precincts of different types and in different locations.

[41] Following approval of the first MPDP, each development application for a Reconfiguration of a Lot (ROL) (where development for a house or other form of accommodation on a lot is intended to occur subsequently by self-assessment or code assessment without a further ROL approval) would be accompanied by a Vegetation Management Plan (VMP) a Development Envelope Plan (DEP) and a Local Population Distribution Plan (LPDP).

[42] The preparation of a VMP would be informed by a survey of existing trees with a diameter of 30 cm at 1.3 m above ground level. The DEPs are intended to restrict the area of any individual site which may be cleared of vegetation for development.

[43] It is intended that, at the ROL stage, aspects of the development such as the alignment of streets and the size and location of individual allotments and the development envelopes within them could be varied in order to be sensitive to the preservation and protection of valuable on site vegetation15.

[44] It was pointed out, on behalf of the co-respondent, that the POD makes the protection of vegetation subject to the realisation of development as otherwise contemplated in the POD. For example, it provides as follows (emphasis added):

14 That document is not part of the Plan of Development but shows, indicatively, what might be expected.

15 Exhibit 11C p.61 s 4.3.3.

19 ?A VMP optimises the protection of vegetation that is valuable for habitat purposes and other reasons having regard to the development outcomes required for the site of the proposed lot reconfiguration16.?

?A DEP optimises the protection of vegetation that is valuable for habitat purposes and other reasons and has been identified in the VMP vegetation survey …having regard to the development outcomes required for the site of the proposed lot reconfiguration…17.?

Further, if the probable solutions to the relevant performance criteria in the applicable codes are to be adopted then lot reconfiguration plans, DEPs and VMPs lodged in support of ROL applications in its mixed use, resort and housing precincts should (emphasis added) ?optimise the retention of vegetation on the development site having regard to the imperative to develop the site? for the relevant purpose.18 [45] What constitutes vegetation of value is undefined in the POD. That is presumably to be left to professional judgment consequent upon the vegetation survey. The significance of these matters in determining the sensitivity of the proposal to the values of the site is discussed later in the context of the fauna, flora and biodiversity issues.

The Statutory Planning Documents [46] It has already been observed that this Court must decide the appeal on the basis of the laws and policies applying when the application was made (11 August 2004), but may give weight to later laws and policies. The planning scheme in force when the application was made was the 1997 Transitional Planning Scheme. The State Coastal Management Plan (August 2001) was also in force19.

[47] The later statutory planning documents discussed in this case are:

(a)

the 2005 IPA Planning Scheme; (b)

the Wide Bay Burnett Regional Plan (2011);

16 Exhibit 11C p.60 s 4.2.3.

17 Exhibit 11C p.61 s 4.3.3.

18 See the Plan of Development Codes for the Mixed Use Precinct PS-7, Resort Precinct PS7 and Housing Precinct PS9; exhibit 11C p.25 & p.33.

19 State Planning Policy 1/03, mitigating adverse impacts of flood, bushfire and landslip (SPP 1/03)

was also in force, but did not feature in the debate on the issues pursued at trial.

20 (c)

the State Planning Policy 3-11 and the Queensland Coastal Plan (February

2012); (d)

Temporary State Planning Policy 2/12 (August 2012); (e)

the Draft Coastal Protection State Planning Regulatory Provision – October

2012 (2012 DCPSPRP); and (f)

the Coastal Protection State Planning Regulators Provision – April 2013 (CPSPRP)

Further, the Council has published a draft new planning scheme, to which regard may be had pursuant to the Coty principle20. The State has also published a draft State Planning Policy.

Documents in force when the application was made

1997 Transitional Planning Scheme [48] The Transitional Planning Scheme was prepared under the now repealed PEA and adopted on 19 December 1997. This development application was made towards the end of its life.

[49] The RS2 land was included in the Rural Zone under the Transitional Planning Scheme. The intent of that zone relevantly provides (emphasis added):

?This zone is intended to conserve areas of agricultural, open space and scenic significance and to allow for the conduct of a broad range of rural activities. It is also intended to preserve some land for future urban, rural residential or other purposes designated in the Strategic Plan or a Development Control Plan. In such cases, favourable consideration will only be given to applications for development or subdivision which do not compromise the use of the designated area for its intended purpose.?

[50] It has already been observed that the uses for which preliminary approval is sought include those which were prohibited in the Rural Zone. The Statement of Intent however, acknowledges that, for some land, the Rural Zone was used as, in effect, a ?holding zone? (pending eventual rezoning) for future urban or other purposes designated in (relevantly) the Strategic Plan. Accordingly, it is the Strategic Plan to

20 Coty (England) Pty Ltd v Sydney City Council (1957) 2 LGRA 117.

21 which reference must be directed to determine whether the proposal is consistent with the Transitional Planning Scheme.

[51] The Strategic Plan recognises that ?the Cooloola Coast comprises nationally significant environments and tourist attractions?. The goals of the Strategic Plan are:

?

?To provide throughout the Shire, a broad range of interesting, safe and comfortable environments for living, working and visiting; ?

To enhance the economic, cultural and social wellbeing of the Shire; ?

To provide for orderly and efficient development of the Shire and promote public and developer confidence in Council‘s development intentions; ?

To ensure that development respects the principles of ecologically sustainable development.?

[52] Insofar as the achievement of those goals is concerned, the Strategic Plan provides:

?The goals are to be achieved by dividing the Shire into Preferred Dominant Land Use designations, setting objectives for development in each, managing development in accordance with implementation criteria developed to satisfy the objectives and implementing the provisions of the Planning Scheme.

Preferred Dominant Land Uses embody the preferred development strategy for the Shire. They guide the Council and its decisions on land use matters, but do not confer land use rights in themselves.?

[53] The Strategic Plan includes an ?Urban? PDLU designation which:

?Comprises the Shire‘s substantial established urban areas and indicates the preferred direction and extent of their growth during and beyond the life of this planning scheme.?

The RS2 site is not within the urban PDLU.

[54] The Strategic Plan also includes a Tourism PDLU designation, but elements of that designation are not identified on the Strategic Plan Map. The Statement of Intent for the Tourism PDLU acknowledges the significance of Rainbow Beach:

?because it is the principal entry point to Fraser Island, the Great Sandy National Park and Inskip Point and a coastal resort in its own right.?

[55] As Mr Summers (the town planner called by the fourth to eighth respondents by election) pointed out, =Rainbow Beach‘ is there discussed as distinct from Inskip Point, to which it is an entry point. That does not mean that tourist development is not to occur on Inskip Peninsula. At least that part of the Inskip Peninsula which is

22 developed as RS1 contributes to the tourism role of Rainbow Beach, while other provisions of the Planning Scheme (discussed below) envisage that some form of ecotourism/residential development might be appropriate on RS2.

[56] The objectives and implementation criteria for the Tourism PDLU envisage that the tourist role of Rainbow Beach will be enhanced. Section 1.13.3.2 provides:

?Rainbow Beach is a small modern coastal resort town. It does not portray any definite character other than a consistent low rise form in its built environment and obvious visual links and convenient access to the beach. Its

continuing tourist role will be enhanced by fostering development of low rise but higher than the existing shopping centre and by encouraging modern light and airy themes in the architecture which emphasises its holiday environment. In assessing applications for motel or holiday accommodation within the tourist accommodation precinct, Council will endeavour to ensure these aims are met.?

[57] The RS2 site is within the ?Environmentally Significant Areas? PDLU designation on the Strategic Plan Map and has an ?Opportunity Area? overlay. The statement of general strategy for the Environmentally Significant Areas PDLU includes the following:

?The Environmentally Significant Areas Strategy aims to identify, manage and protect valued habitats and stands of remnant vegetation significant to the Shire‘s ecological sustainability, areas representing the intrinsic character of a locality and/or landscape elements of outstanding significance.?

[58] The first of the objectives for such areas is as follows:

?1.10.3.1 To protect, manage and enhance the Shire’s important natural environments.

The protection of fauna and flora habitats and corridors is essential to the maintenance of the Shire‘s biodiversity and the aesthetic appeal of its natural environments. Much can be achieved through education and sound ecological management, however the field in which the Strategic Plan is influential relates to managing the impacts of development on land comprising or neighbouring designated Environmentally Significant Areas.?

[59] The second objective relates to the beach and foreshore. It provides as follows:

?1.10.3.2 To preserve the beach and foreshores as a major public recreational resources and natural open space area of visual significance and to ensure inappropriate development does not occur in areas subject to natural coastal processes Council recognises the value of the Shire, and particularly to the tourism industry, of retaining high quality beaches supported by beach protection buffer zones with reasonable access.

23 To preserve and enhance the natural character and features of the Cooloola Coast as a recreational setting, Council in conjunction with the beach protection authority and other relevant government departments aims to prevent development that would detract from the natural character, and to impose suitable planning controls on land use and development to ensure the natural attributes are protected.?

[60] The implementation criteria include that, in considering applications for development, Council will seek, amongst other things, to require the dedication or maintenance of beach protection buffer zones, which are adequately sized, on ocean beaches.

[61] The Strategic Plan goes on, in the provisions dealing with the Opportunity Area, to acknowledge that the RS2 site is the subject of a development lease and has some development potential as well as environmental sensitivity. It seeks to ensure that any development is compatible with the environmental values and character of the area and that it occurs in accordance with the principles of ecologically sustainable development. In that regard, s 1.10.3.3 provides (emphasis added):

?1.10.3.3 To retain the unique features of Inskip Peninsula and surrounding areas and ensure that any development is compatible with the environmental values and character of the area, and occurs in accordance with the principles of ecological sustainable development.

An opportunity area has been mapped on land designated as an environmentally significant area at Inskip Peninsula. While detailed planning for this area shall be addressed through the Cooloola Coast Development Control and possibly a local area plan, Council recognises both the site‘s potential for development considering existing development leases and its environmental sensitivity. While the site presents substantial development opportunities, because of its favourable location, opportunities are constrained in a number of ways including, uncertainty as to future availability of water resources for reticulation, the requirements of the Great Sandy Region Management Plan, the erosion prone areas and the need to conserve natural values.

Any application for development over this site may be considered to be premature prior to the gazettal/adoption of the Development Control Plan/Local Area Plan, however, Council envisages that a low density, low key, low rise, style of eco tourism resort/residential development(s) with significant retention of private and public open spaces may be appropriate for the site, providing appropriate planning and environmental management strategies and practices are devised, and community and planning need can be demonstrated.?

[62] The implementation criteria for that provision are as follows:

?In considering development applications in this area Council will:

24 ?

have regard and take into account the recommendations of the Great Sandy Management Plan, and any subsequent Development Control Plan and/or Local Area Plan; ?

ensure that the provisions and requirements of ss 1.10.3.1 and 1.10.3.2 are followed and implemented; ?

liaise with other statutory authorities to ensure their interests are considered and protected as appropriate; ?

require the applicant to demonstrate the proposed development areas will not experience unacceptable impacts from natural hazards including cyclones, storm surges, long term changes in water levels, ground water discharge and other natural events of concern in coastal eco systems; ?

require urban design principals to be incorporated which seek to ensure the scale, bulk, design and character the development reflects and is sympathetic to the existing amenity and where possible enhances the natural beauty of the area; ?

require that development is designed to maintain a ?sense of place?

through limiting the intensity of development to within the environmental carrying capacity of the area, attention to the retention of visual focal points and buffers, incorporates design themes which draw from the natural characteristics of the area, including strict controls on the bulk, scale and height of any structure and the retention of significant portions of the site in open space areas; ?

require the submission of an environmental assessment report or such other environmental analysis and management planning as is considered appropriate which identifies existing environmental attributes, systems and current trends in natural processes, the potential impacts of the proposed development and any alternative options which could be considered, and measures proposed to minimise or ameliorate these impacts during the construction and ongoing use of the site; ?

ensure public access to the beach and foreshore is provided at appropriate locations and provisions for public facilities (eg car parking, public toilets, emergency services, recreational facilities and parks) are made; ?

Encourage the incorporation of best management practices in the service reticulation and waste management systems installed in conjunction with, or as a result of, the development.?

[63] The Great Sandy Region Management Plan (1994-2010), to which reference is made, contained a bullish statement about future potential growth as follows:

?The future land use on Inskip Peninsula will have a major influence on the future management of the Region. The population of Rainbow Beach/Inskip Peninsula is expected to grow to between 5 000 and 8 000 making the centre a substantial holiday destination and the southern gateway to Fraser Island.?

25 In relation to the land the subject of development leases, it also states:

?Proposals for resort and residential development cover substantial areas of the Peninsula under development leases. These leases were granted in compensation for surrendered sand minding interests on Fraser Island, Moreton Island, Cooloola and on the central Queensland coast.

Reservations have been expressed about the extent and type of development proposed for Inskip Peninsula. Key areas of concern relate to the supply of water, disposal of sewage and waste, traffic management issues and the impacts of the projected population and proposed development on the values of the Region particularly in relation to the area‘s fisheries.?

As discussed later, nothing like that extent of growth has occurred, or is likely to occur in the near future.

[64] Whilst the stated objective recognises that the RS2 site has development potential it also recognises its environmental sensitivity and that the development opportunities of the site are constrained. It does not provide any specific support for the extent of development for which the appellant seeks a preliminary approval.

[65] The Objective contemplates that greater guidance would be given by creation of a Development Control Plan or a Local Area Plan. That did not eventuate during the life of the 1997 Plan. The reference to development applications potentially being premature prior to the gazettal or adoption of such a plan should not, in the circumstances, stand in the way of a consideration of the subject proposal.

[66] It was submitted that serious conflict with s 1.10.3.3 arises by reason of the proposal being beyond the ?low density, low key, low rise, style of eco tourism/residential development/(s)? description of what council ?envisages? may be appropriate. The expressions ?low density?, ?low key? and ?low rise? are relative notions. Whether the subject proposal fits those descriptions should be judged in the context of the planning scheme in which those terms appear and the site and area to which they apply.

[67] The proposal is obviously large, particularly in the context of Rainbow Beach. I acknowledge, as the appellant pointed out, that the site over which the proposal is spread is also large and that the POD contains a number of provisions which aim to ensure that development ?fits? with its context, including by limiting the height of

26 buildings in the various precincts to prevent visual dominance of the landscape setting21.

[68] It was also pointed out that the provisions make reference to the Great Sandy Region Management Plan which, amongst other things, seeks to direct new tourist and commercial development towards Hervey Bay, Maryborough and Rainbow Beach and away from Fraser Island itself.

[69] Notwithstanding those observations, there are, quite apart from the quantum of development for which preliminary approval is sought, components of the proposal which make it difficult to describe what is envisaged, in its entirety, as simply a low density, low key and low rise eco-tourism resort/residential development. I note,

for example, that the POD makes provision, in sub-precinct H4 of the Housing Precinct, for what it accurately refers to as ?high density apartment style housing?.

The resort precinct contemplates the possibility of multi-residential development to six storeys, subject to impact assessment. Substantial (particularly in the context of Rainbow Beach) commercial development is provided for. There is also significant opportunity for education, health and community services in the community precinct.

[70] I have not approached the matter on the basis that the strategic plan necessarily sets its face against any proposal which, in any way, departs from the description of what the ?Council envisages … may be appropriate? in the absence of the anticipated Development Control Plan or Local Area Plan. Had conformity with that description been intended to be mandatory, then stronger language would have been expected. Further, I note that the expression was not carried forward into the

2005 Planning Scheme, to which substantial weight should be afforded in this case.

I accept that departure from what the Council ?envisages … may be appropriate for the site? does not itself establish conflict and is, in this case, far from determinative.

[71] Mr Summers was of the opinion that the proposal does not exhibit an appropriate relationship with the Rainbow Beach township and does not represent orderly planning. He regarded both the 1997 Planning Scheme and the 2005 Planning

21 See, for example, S0-2 of the Mixed Use Precinct; exhibit 11C p.21-22.

27 Scheme (discussed later) as establishing a relationship or hierarchy which the proposal offends. In the joint report22 he said:

?Mr Summers concludes that there is a clear order within the Strategic Plan in the

1997 Transitional Planning Scheme, where Rainbow Beach is centre and staging point for journeys to Fraser Island, the Great Sandy National Park and Inskip Peninsula, where the Inskip Peninsula because of its wilderness feel is a recreational resource and character area and Lot 22 has some capacity to support development; however the extent and intensity of that development:

(a) Is of a scale that does not warrant an Urban Area PDLU, as applied to Rainbow Beach and Rainbow Shores 1; and (b) Should be subservient to Rainbow Beach.?

[72] That reads a little too much into the Planning Scheme. The decision not to apply an Urban Area PDLU to RS2 is unsurprising, given the unresolved constraints to achieving development. In the absence of a Development Control Plan/Local Area Plan, the provisions of the scheme do not qualify the extent of development potential of RS2 in either absolute or relative (relative to Rainbow Beach township)

terms, beyond the unspecific description of what ?Council envisages … may be appropriate?.

[73] Ultimately, the consistency or otherwise of the proposal with the Transitional Planning Scheme turns on whether it is consistent with the provisions dealing with the Opportunity Area overlay in the context of the underlying Environmentally Significant Areas PDLU and having regard to the intent for tourism in Rainbow Beach. That raises issues which are considered later.

The State Coastal Management Plan (August 2001)

[74] The co-respondent, as a concurrence agency, assessed the development application against the State Coastal Management Plan, which was a statutory instrument created under the Coastal Protection and Management Act 1995. The reasons for refusal of the subject application, as directed by the co-respondent, related to three policies within the SCMP namely policies 2.1.2, 2.8.1 and 2.8.3.

[75] Policy 2.1.2 seeks, amongst other things, to ensure that:

?To the extent practicable, the coast is conserved in its natural or non-urban state outside of existing urban areas. Land allocation for the development of

22 Exhibit 5 tab 15 para 163.

28 new urban land uses is limited to existing urban areas and urban growth is managed to protect coastal resources and their values by minimising adverse impacts.?

RS2 is not in an existing urban area.

[76] Policy 2.12 also provides, in part, that:

?Urban growth is managed to protect coastal resources and their values by minimising adverse impacts?

Whether the site has coastal resources worthy of protection and whether the proposal minimises adverse impacts is discussed later.

[77] Policy 2.1.2 also states, in part, that:

?Growth of urban settlements should not occur on or within erosion prone areas, … sites containing significant coastal resources of … ecological value, or areas identified as having or the potential to have unacceptable risk from coastal hazards.?

As discussed later, RS2 has significant ecological value and, in part, is subject to potential erosion and storm surge.

[78] Policy 2.8.1 relates to areas of State significance (natural resources). Areas of State significance include areas comprising ?significant coastal dunal systems?. That is a defined term. The relevant policy states, in part:

?Land identified to be developed in the future for urban … uses in regional plans, planning schemes … is to be located outside of =areas of state significance (natural resources)‘. Existing urban … uses within =areas of State significance (natural resources)‘ will not expand in these areas unless it can be demonstrated that there will be no adverse impacts on coastal resources and their values. If a use or activity that has adverse effects is to occur within =areas of State significance (natural resources)‘, it must have a demonstrated benefit for the State as a whole …?

[79] Four ?areas of state significance? (natural resources) are identified in policy 2.8.1 of which the relevant one is ?significant coastal dune systems?. Whether the RS2 site is part of a ?significant coastal dunal system? and, if so, whether it would have adverse impacts and, if so, whether it has been demonstrated that there would be a net benefit for the State as a whole from it proceeding are matters discussed later.

29 [80] Section 2.8.3 seeks to safeguard biodiversity on the coast ?through conserving and appropriately managing the diverse range of habitats including … dune systems …?. It states that the following matters are to be addressed to achieve the conservation and management of Queensland‘s coastal biodiversity:

?(a) the maintenance and re-establishment of the connectivity of ecosystems, particularly remnant ecosystems; (b) ensuring viable populations of native species continue to exist throughout their range, by maintaining opportunities for long-term survival, genetic diversity and the potential for continuing evolutionary adaption … (c) the retention of native vegetation wherever practicable …?

The proposal involves substantial destruction of native vegetation on RS2. The impact of the proposal on biodiversity is discussed later.

[81] While the State Coastal Management Plan was a relevant document for assessment of the application, its significance, particularly as a =stand alone‘ planning document, has been overtaken. First, the relevant Minister identified the State Coastal Management Plan as having been appropriately reflected in the 2005 Planning Scheme. It is the provisions of that planning scheme, as they relate to the subject application, to which weight should be attached in the assessment of the application. Weight should not be given to the State Coastal Management Plan in a way which departs from the manner in which it was reflected in the 2005 Planning Scheme23. Secondly, and more recently, the Coastal Management Plan was superseded when State Planning Policy 3/11 (discussed later) came into effect.

Subsequent statutory planning documents

2005 IPA Planning Scheme [82] The current Planning Scheme took effect on 31 March 2005, some seven months after the Development Application was made. It has been in effect for eight years and, indeed, is near the end of its life. It was uncontroversial that, as between the

23 Celledoni v Johnstone Shire Council [2008] QPEC 104.

30

1997 Planning Scheme and the 2005 Planning Scheme, it would be unrealistic to deny the latter primary weight. The 2005 Planning Scheme did not, however, take a radically different approach to the subject site.

[83] The Desired Environmental Outcomes for the Cooloola Shire include:

?(4) the role of Rainbow Beach as a major coastal tourist destination in the shire is reinforced; … (7)

the amenity, cultural heritage, ecological and recreational values of significant natural features including the Great Sandy National Park, Inskip Point and other coastal areas… are protected and enhanced; … (9)

adverse effects on the natural environment are minimised with respect to the loss of biodiversity and significant natural vegetation, soil degradation, interference with natural coastal processes and water pollution due to erosion, chemical contamination, acidification, salinity, effluent disposal and the like.?

[84] The 2005 Planning Scheme includes a Strategic Framework, the provisions of which are not intended to provide a basis for development assessment, but are a guide for development related decisions of Council, developers and the community generally. Section 1.2.3 of the Strategic Framework identifies relevant outcomes for residential development. The preferred settlement pattern is said to be indicated by the ?Urban? nodes on, relevantly, Strategic Map SM2, Cooloola Coast. The RS2 site is outside the Urban designation on that map.

[85] Section 1.2.6 of the Strategic Framework identifies that the following outcome is sought by the Planning Scheme for tourist orientated development:

?Rainbow Beach and Tin Can Bay are the major tourist centres on the Cooloola Coast. Tourist orientated development including accommodation, of an appropriate scale, retailing and services are appropriate within the identified tourist service areas of both towns. Mixed use development is encouraged particularly commercial and service uses on ground level and accommodation above or to the rear.?

The RS2 site is not included within an identified tourist service area.

[86] Section 1.2.10 of the Strategic Framework identifies the following outcome which is sought by the Planning Scheme for environmental protection:

31 ?The Planning Scheme identifies some areas having environmental significance because of existing values and actual or potential land degradation, including salinity, erosion and acid sulphite soils. Some of these areas are shown on … Strategic Map SM2, Cooloola Coast, and others are shown on overlay maps, and actual hazard maps or advisory maps.

Development within or near some of these areas is subject to specific codes to protect the Shire‘s natural features and resources.?

The vast majority of the RS2 site is mapped as being of regional ecosystem value on Overlay Map OM4 and the proposed development is therefore subject to the relevant applicable code. The Scheme provides that, to the extent of any inconsistency, a provision in an overlay code prevails over a provision in any other code24.

[87] The Planning Scheme area is divided into three parts. The RS2 site falls within the Cooloola Coast Planning Area. That area is, in turn, divided into zones. The RS2 site is included in the Rural zone.

[88] Division 5.4 of the Planning Scheme contains a Cooloola Coast Planning Area (excluding Rainbow Shores Precinct) Code. The Overall Outcomes for the Code include that significant environmental areas are conserved and protected from adverse effects of development25. Specific reference is made to the RS2 site as follows:

?Lot 2, MCH 803497 remains an undeveloped urban development lease area until conflicting issues about:

(A)

The environmental significance of the site; (B)

Water availability and supply for Cooloola Coast; (C)

The site‘s susceptibility to natural hazards; (D)

The potential for development of the site whilst maintaining its natural values; (E)

The need for further urban development at the Cooloola Coast to service projected population; and, (F)

Other State interests are resolved, allowing Council to consider the sensitive development of the site, in accordance with sound town planning and urban design principles, and best management practices for water and sewerage

24 Cooloola Shire Council Planning Scheme 2005 s 2.7(2).

25

2005 Planning Scheme s 5.4.3(2)(b).

32 reticulation, water conservation, waste disposal and construction methods.?

[89] The Planning Scheme envisages that the RS2 site is to remain undeveloped until those conflicting issues are resolved. Those issues include the environmental significance of the site, its susceptibility to natural hazards and the need for further urban development. The implied acknowledgment that the land might be suitable for some form of urban development, if and when the conflicting issues are resolved, suggests that, as was the case with the earlier Planning Scheme, the Rural zone is potentially performing something akin to a holding zone function with respect to the RS2 site. The provisions however, do not provide any specific support for development of the scale and intensity proposed.

[90] Table 5:13 of the 2005 Planning Scheme sets out the specific outcomes and probable solutions for the Cooloola Coast Planning Area (excluding Rainbow Shores Precinct)26. Specific Outcome SO1 identifies commercial premises, multi-

residential and shop uses as inconsistent uses in the Rural Zone. As with the 1997 Planning Scheme, the minimum lot area for sub-division is 100 hectares. Those provisions however, need to be read in the context of the role which the Rural Zone plays with respect to the RS2 site. They should not be seen as an insurmountable hurdle to development of an appropriate kind, provided the conflicting issues referred to in the Overall Outcomes are resolved.

[91] The RS2 site is also subject to the Conservation Significant Areas Code. The Overall Outcomes for the Code include an intention that ?areas identified as having conservation significance are protected from development or the effects of development that may cause degradation of those areas? by, amongst others, ?loss of ecosystems, habitat or connectivity value?.

[92] Further, an Overall Outcome for the Conservation Significant Areas includes that:

?(b) Sensitive design maximises the retention, protection and enhancement of:

(i)

Vegetated remnants and minimises their edge to edge perimeter ratios to enhance the potential for the long term survival of significant fauna and flora species;

26 The Rainbow Shores Precinct covers RS1, but does not extend to RS2.

33 (ii)

Connectivity value areas to maximise the general genetic dispersal of significant flora and fauna species; and …?

[93] Two specific Outcomes for the Conservation Significant Areas provide, in part:

?SO1 development within State or Regional Ecosystem Value Areas is avoided.

… SO14 development within Endangered, Vulnerable or Rare Flora or Fauna species Habitat Value Areas is avoided.?

The RS2 site is mapped as having regional ecosystem values across the vast majority of the site27 and EVR28 habitat values at the north-western end29.

[94] It was submitted, for the appellant, that the specific outcomes of the Conservation Significant Areas Code should be read in conjunction with other provisions of the Planning Scheme and, in particular, the provisions of the Cooloola Coast Planning Area (excluding Rainbow Shore Precinct) Code, which contemplate that the RS2 site might be capable of urban development in the event that conflicting issues are resolved. It was submitted that:

?In context, if the criteria listed in s.5.4.3(2)(q)(ii) are satisfied, so too will be the requirements of SO-1 and SO-14. Were it otherwise, the fact that the RS2 site is mapped as ?Regional Ecosystem Value Area? on Overlay Map 4 sheet 2 would, together with SO-1 and SO-14, deny s.5.4.3(2)(q)(iii) any operation. Further, it would confer on SO-1 and SO-14 an operation prohibiting development in the circumstances to which they apply. Plainly, that could not have been intended.?

[95] As was submitted on behalf of the co-respondent however, not only does the Scheme give primacy to the Conservation Significant Areas Code (as an overlay code) in the event of any conflict with the provisions of any other code, but those two parts of the Planning Scheme are, in any event, not necessarily inconsistent.

The probable solutions for SO1 and SO14 envisage that development may be appropriate either where development does not occur within the mapped areas or where, following on-site investigations, that part which is to be developed is found not to have the relevant values.

27

2005 Planning Scheme OM4/1 sheet 2.

28 Endangered, Vulnerable or Rare Fauna or Flora Species.

29

2005 Planning Scheme OM4/2 sheet 2.

34 [96] There is a small proportion of the site (in the formerly mined area) which is not within the mapped regional ecosystem area, but the proposed development extends more generally across the site. Substantial on-site investigations of values have been performed for the purposes of this case. Those are discussed later. The proposal envisages substantial development within parts of the site which are not only mapped as having regional ecosystem value but which, following the onsite investigations, have been established as supporting vegetation of regional ecosystem value. There is conflict with the Code. The proposal also envisages substantial development in parts of the site which have been demonstrated to provide habitat for rare or vulnerable fauna and near threatened flora.

Wide Bay Burnett Regional Plan [97] The Wide Bay Burnett Regional Plan (WBBRP) is the pre-eminent planning document for the region30. It took effect on 29 September 2011 under the SPA.

The regulatory provisions however, in Part E, have ceased to operate in consequence of Parliament‘s failure to ratify them. Further, the 2012 DCPSPRP and its successor, the CPSPRP, suspended the operation of Part 2.2 of the Regional Plan. The provisions of the Regional Plan otherwise however, are provisions to which the Court may give such weight as it thinks fit.

[98] Part B of the Regional Plan describes the regional framework. This includes three components: a strategic direction; regional settlement patterns; and sub-regional narratives. The relevant sub-regional narrative applying to Rainbow Beach acknowledges that nature-based tourist hospitality is a locally relevant industry in Rainbow Beach. Further diversification of local employment and economic activity will be supported where appropriate. The narrative also notes the ?limited opportunities? for broad hectare residential growth within residential towns and that ?the expansion of urban activity, particularly residential development beyond existing urban areas, is severely limited?.

[99] Part C of the Regional Plan states the Desired Regional Outcomes for the plan area.

The RS2 site is included in the Regional Landscape and Rural Production Area and

30 To allege that does not mean that it must be given decisive weight in relation to the application.

35 is also mapped as being of High Ecological Significance31. The intent of the Regional Landscape and Rural Production Area is set out in Part D as follows:-

?Regional Landscape and Rural Production Area: