Note from Candobetter Editors:

Since this article is so popular, we feel we should tell readers that there is more, much more by Antony Boys, in Sheila Newman (Ed.) The Final Energy Crisis, Pluto, UK, 2008. Antony has two long articles in it: The first is about how North Korea coped without cheap soviet oil. The second evaluates in detail Japan's carrying capacity in the Edo period, then looks at changes to agriculture and population during Japan's industrialisation, then looks at how Japan may fare with oil depletion.

1. Rationale

A short while ago I wrote a "food and energy survey" of the city where I live in Japan to try to get some idea of how the city might do if there was an extended food and energy crisis. A pdf file of the survey is attached to this article. Please feel free to read and comment on it. Until October 2004, what is now Hitachi Omiya City had been Omiya Town, one other town and three other villages, and although I had lived in Omiya Town since 1986, when the town and village amalgamation occurred I had only a vague idea of what the new city consisted of.

Take the word "city" with a degree of skepticism, by the way. This is not London or New York. In Japan, any administrative unit with a population over 30,000 can be a "city". That can mean that you have a small commercial and administrative district with a large rural hinterland, as we have here. Don't go looking around for the "city". There really isn't one.

After writing the survey, I sent it off to several people for comments. One of these was my good friend Martin, who lives near Tokyo. Martin is writing a book about food in Japan, so he has a good feel for the subject, but the problem was that he had very little idea of what the city looked like. Martin came up to visit my family a few days ago, and so we set off on a five-hour drive around the city so that we could both get a much better idea of what is there. You can also see Martin's version of the trip on his blog.

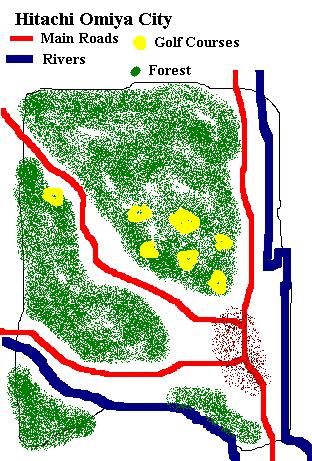

Here's a sketch map of the city. It is very roughly a square, each side being about 12 miles, or 19 km. The brown shaded area near the southeast corner of the city is the main commercial and administrative area. An interesting feature of the city that you can see from the map is that there are two quite substantial rivers that approach each other and come quite close together at the southern end of the city area. The river flowing north to south on the east is the Kuji River and the river flowing roughly southeast in the south of the city is the Naka River.

One further notable geographical fact is that the city is on the northern edge of the Kanto Plain, the large flat area that surrounds Tokyo.

2. What's different about Japanese Agriculture?

Martin and I decided to drive along some of the main roads as far as the border with the next administrative unit, and to stop to take pictures every time we saw something interesting or representative of the city, or of Japanese farming in general. Perhaps three of the most representative features of Japanese farming are:

1) Field areas are small,

2) Farmers are mostly older people,

3) Capital intensity is high.

The first two are fairly clear, but the third feature refers to the fact that the amount and size of machinery is out of proportion to the land it is used to work. This is also one factor in the high energy-intensity of Japanese agriculture, which is expressed either in terms of high levels of chemical (fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, and so on) inputs to the land, or in terms of very intensive labour inputs. In addition, for some fruit and vegetable crops, large amounts of plastic sheeting for covering the ground or for making hothouses are used, and in the colder seasons kerosene is sometimes used to heat the hothouses from the inside.

I will try to illustrate these three features with photographs taken during our half-day trip.

3. A Local Farmer

Actually, as we came out of the house, I saw that the farmer who is now growing a crop of upland rice (i.e. a rice variety that does not need to be grown in a wet paddy field) right next to my house had turned up on his morning round of his fields. We went over and said hello and I took out my camera and snapped him right there. The evening before, Martin and I had passed by another of his fields which is on my regular dog walk. The field is a bit less than one-tenth of a hectare and is now covered with a dense growth of soybeans. It's very 'clean', but it's interesting how it got that way. Since I walk our dogs along the same route nearly every day between about four and five in the afternoon, I had seen what had happened in the field over the few weeks since the soy had been planted. The farmer had been out there with a tiny hand-pushed machine (like a small manual lawn mower about 20 or 25 centimetres wide) almost every day, slowly and labouriously, and with meticulous care, removing anything green in the rows between the soybean plants. Sometimes he was just walking up and down between the rows, with his eyes on the ground, occasionally bending down to pluck out a weed. Only once in the two weeks or so that I walked by the field every day did we greet each other, because he was concentrating so hard on what he was doing that he probably didn't notice me, and I didn't want to disturb his concentration by calling out to him.

Martin and I agreed as we walked the dogs that this man's work is now being replaced by herbicide-resistant GE soybeans. If you are farming hundreds of hectares of soybeans, perhaps that makes sense to you. But it does not make sense in about 90% of Japanese farming, which is done something like I describe here, on very small plots of land. (There is NO commercial planting of GE soy in Japan.) When I visited Kumamoto Prefecture some years ago, the topography was so hilly/mountainous, that field sizes were even smaller than where I live. The people there told me that in the 1950s and early 60s they had switched to chemical/mechanical farming along with everyone else, but had given up a few years later because it just did not make economic sense on their small fields. That's why now Kumamoto Prefecture has more organic farming than any other area in Japan. I didn't hear anyone complain about it, though.

This farmer, growing his upland rice and soybeans on small fields here and there in the area (and is also well-known for his good vegetable seedlings) is about in his mid-seventies. I don't know anything about his children, but I have never seen any younger people in his fields. The 'funny' thing was that when Martin and I arrived back at my house about two in the afternoon, at the end of our drive around the city, there was a bicycle standing at the edge of the field with the upland rice growing in it; the farmer's wife had turned up to do a little weeding!

4. Small fields, disproportionally large amounts of machinery

First of all, we drove out along the main road that roughly follows the course of Naka River, which cuts across the southern end of the city. We reached the border with the next prefecture (Tochigi Prefecture), took a few pictures and turned back again. Here's a picture of what the river looks like at this point.

As we drove back towards the town again, we saw a brilliant example of feature number three (and one) taking place right up ahead; a farmer preparing a miniscule patch of land with a tractor. You can imagine his concern as, early on what should be an uneventful Monday morning, a car screeches to a halt and two foreigners jump out and start to take pictures! He smiled as we explained who we were and what we are doing (Martin's Japanese is pretty good too) and then went on to his next job for the morning.

This example is clearly extreme. I'm sure small plots of land as small as this are farmed all over the world, but do the farmers come round to prepare the ground with a tractor? These photos will make some of you, used to farming 100s of hectares at a time, laugh your heads off, but it is pretty typical of the way Japanese farming works, as you will see below.

5. Japanese agriculture: Elderly individuals with little family or local solidarity

A little further on, we saw a sign for "ostriches" and decided to take a look, expecting to see some kind of ostrich farm, but there were only the two giggly specimens that you can see in the chain-link pen here.

As we were having a laugh about the size of the 'ostrich farm', Martin caught sight of something interesting in a paddy field close by; a farmer with a basket on his back weeding the field.

We decided to go over and investigate. The farmer noticed us immediately as we stood at the edge of the field taking pictures and decided to come out and talk to us. He turned out to be extremely friendly and open, as most Japanese farmers are. He told us that his main work was growing vegetables for sale and that the rice he would harvest from the paddy field was just for family consumption. Looking around, we could see that there were plastic sheet hothouses nearby for preparing vegetable seedlings, and also vegetable fields.

I asked the man if the vegetables were his main source of income. I half expected him to say that he had other family members who bring in more income, but he did not, simply replying 'yes' to my question. I imagined that he lived nearby with his wife. I asked if he had been farming long and he said he had been farming in the same place for 55 years - he told us he was now 65.

He mentioned that he was doing his vegetable farming business as a group. I was interested in this because working as a group is one way of reducing the capital-intensity of the farming; the group could buy machines and chemicals as a collective, thereby holding down the average cost to each individual farmer. Martin and I had talked about this the previous day, and I was hoping we had perhaps run into a positive example of feature number three. I asked the farmer how many people were in the group. He said that they had started as seven, but were now down to two. That was disappointing, but he agreed with us that there were advantages to working as a group and I encouraged him to see if he could find more local farmers he could work with.

I was interested to know if the administrative areas had changed before and he told us that the area had been a small village before the previous round of town and village amalgamations in the 1950s. Then the area had become Gozenyama Village, which was then amalgamated into Hitachi Omiya City in October 2004.

I told him that I had recently completed a survey of the city to get some idea of how the city would fare if there were a sudden 'food and energy' crisis in Japan, given all the 'news' we were getting from the media about global food and energy problems, as well as the prices of gasoline at the pump and food in the supermarkets.

He seemed to be quite interested in this, but then, quite unprompted, began to talk about his son. I suddenly realized that we had stumbled upon a typical example of feature number two.

The farmer told us that his son, who lived with him in the house close by, was 38, but had only just recently begun to help out with the farmwork by sometimes cutting the grass (at the edges of fields and so on) with a kusaharaiki, the ubiquitous little two-stoke engine grass-cutter that every farming family here seems to have. The son apparently had no idea how to grow rice or vegetables.

This is absolutely typical of the situation here; children of farming families, with farmland that they will eventually have to take over, but with not a clue about how to grow their own food. I told the farmer that he had better hurry up and pass on his skills to his son, because if there is a problem in the future the son will not want to find himself hungry, and yet with fields that he doesn't know how to farm.

Martin told him that he could tell his son that two "European specialists" had just visited him and told him to do just that. I thought that was quite amusing. I don't know if the ostriches found it funny as well. Anyway, we exchanged names and I promised to visit him again sometime. In a month or so I will probably drive out and see how he's doing.

6. Prototypical Japanese agricultural scenery

Martin and I then continued on down the road back towards the city 'centre', but turned left onto a small road heading north towards the areas where the golf courses are. I had never driven up this road before, and it turned out to be a very pleasant typical Japanese country road in a low mountain area. We decided to stop and look when we saw a small area of paddy fields nestling in a tiny valley.

In hilly areas in Japan (all over Asia, actually) you will come across tiny valleys like this where the original stream bed has been built up and leveled so that the farmer can take advantage of the natural water flow of the stream to construct paddy fields. Large areas of paddy fields tend to be areas close to larger rivers and so work on the same basic principle. These small valley paddy fields are generally surrounded by densely wooded hills, as here, and so are fed with the runoff from the woods, usually full of minerals and other nutrients. This is sometimes called the "original Japanese scenery" - a kind of prototypical essence of the Japanese agricultural lifestyle. (You may get some idea of why the Doha Round and so on does not make a lot of sense out here.)

The rice flowers were just 'blooming' in the field so I tried to photograph some of them. If you haven't seen rice flowers before, this is what they look like.

Over the last 30 or 40 years, some of these tiny paddy fields have been abandoned as the owners become older and unable to farm all the land, or as the rice consumption per capita has declined and the government has ordered farmers to take some land out of use - 'set-aside'. Sure enough, the old paddy field at the head of the little valley had been abandoned. The paddy fields are nearly always abandoned from the head of the valley down - pretty obvious really, I suppose - but the main reason is that the top paddy field will always be the least productive because the water temperature is always lowest in that field.

Unfortunately, in this particular case, the little valley backed onto one of the local golf courses, which means that the runoff probably contained high concentrations of chemicals. That would certainly be one good reason for abandoning the top field, though I should think the rice in the other paddies would not be much better. Since there was no one around, we could not ask, but I have a feeling that the farmer is possibly eating the rice he grows in other paddies elsewhere and selling the produce from this little valley into the industrial food chain.

Sometimes one or two of the paddies have been turned into ordinary 'upland' fields, like the one you can see here, so tiny that you can even see the farmer's footprints.

Further up the road, we saw a field with an unusual dark red colour. We stopped to take a few photos. This was a small field of 'akajiso' plants. ("Aka" is red in Japanese. There are red and green varieties of this plant, the green one being called "aojiso". The word "ao" covers a wide range of colours all the way from what we call blue to green.) This is an edible leaf - quite tasty once you get used to it - which is used as a decorative leaf on certain kinds of food, especially sashimi, raw fish slices. If you buy a small plastic tray of sashimi in a supermarket here, the sashimi slices are placed on shredded Japanese radish (daikon) and then decorated with two or three of these leaves. The colour contrasts make the fish look really appetising. This small field of akajiso is maybe one-tenth of a hectare, perhaps a little less. When I got home, I showed the photo to my (Japanese) wife, who immediately exclaimed, "What a big field of akajiso!" (The ostriches probably would have had a good laugh at that.)

7. What Japanese call a "large" area

Martin and I drove up the main road to the border with Tochigi Prefecture close to the northwest corner of the city, enjoying the forests as we went. The trees are mostly Cryptomeria japonica, a kind of conifer in the cypress family. The tree is called "sugi" in Japanese and is sometimes called the 'Japanese cedar' in English, though it is unrelated to the cedars. Being a conifer, it is good for construction wood, but not much good for leaf mold. I am told it is also not a good fuel wood, perhaps because it burns too quickly and fiercely.

We then drove eastwards along a small and very pretty road through the low mountains until we came to the main north-south road, where we turned right to head home again. On the way there is a good lookout spot which overlooks an area of rice paddies close to the Kuji River. In the photo, you can see low wooded hills in the distance, which are on the far side of the river. In the middle distance, if you look carefully, you can see the river embankment. In this area, this is what we would call a 'large' area of rice paddies. Even so, you can see that the individual fields are one-tenth to one-fifth of a hectare each, each one of them owned by different families, with one family having one, two or three fields dotted about here and there. You can also see that some of the fields have been abandoned. It's either 'set-aside' or the owners have become too old to farm the land, or died, and the younger members of the family either cannot be bothered to farm it, or don't know how to, or have moved away to Tokyo (or other conurbation) in search of higher incomes.

8. Final comment

These three features of Japanese agriculture, small fields, age of farmers, and capital intensity, are generally not known to people in the US, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Argentinia, or Brazil and so on, although Asian agriculture is quite similar and people in India and China would be able to relate fairly easily with this description.

Large-scale 'industrial' farming no doubt 'feeds the world'. Without the green revolution, humanity may well have run up against land-population limits in the 1980s or 90s, and Japan relies on industrial agriculture to feed 60% of its population, since only 40% of the food calories needed to keep the Japanese population alive are actually produced here. So what will happen if imports of cheap food and oil cease? That's why I wrote the survey; to try to see whether this small city can survive without 'imports' of food and energy from outside. If you read the survey you will see that there are many problems to be overcome even for a city like this to reach sustainable self-sufficiency (not the least of which is what to do about the hordes of hungry people from Tokyo who will want to relocate here - but that is another story). At least, after reading this and seeing the photos you have a better idea of what the city looks like, and perhaps what life might be like here after "peak oil" becomes really serious.

Please also feel free to comment below on either this 'photo essay' or the survey. If you care to ask questions, please also feel free do do so as a 'comment' and I will try to get around to answering your question(s) within a reasonably short period of time.

Comments

Sheila Newman

Fri, 2008-08-22 13:56

Permalink

Wonderful article

nimby

Fri, 2008-08-22 15:59

Permalink

Japan's forests

Tony Boys

Sat, 2008-08-23 13:25

Permalink

Japan's not quite sacred forests

Hi vivienne,

Thanks for the comment. People do often wonder why Japan imports so much timber and forest products when forests cover about 66% of the land area. SOME forests are considered sacred (around temples and shrines, for example) and are protected (there are National Parks), but the 'real' reason for the imports is, of course, economics. Imported timber is much cheaper, making it uneconomic for Japan to work the forests. This has upsides and downsides. The upside is, naturally, that they still have their forests, but the downside is that the forests are now not maintained or managed, and so their condition is not good. Fortunately, forest fires are few and localised, due to plentiful rainfall, I suppose. However, large areas of forests are completely unmanaged and therefore overgrown. Storm and typhoon damage make the situation worse.

I do not think it quite true to say that the Japanese do not regard their forests as resources. There have been famous cases in the past, the campaign to prevent logging in the Shirakami Sanchi (northeastern Japan, Akita and Aomori Prefectures) in the 1980s is one of the most famous, of huge public opposition to logging in virgin forests. If it were not for cheap imports, however, Japan's forests might look quite different from what they are today.

[There are lumber merchants in the city who cut Cryptomeria for housing contruction]

The forests mentioned in the article, in the city where I live, are Cryptomeria Japonica. That's not because they naturally grow there, but because they were planted in the 1950s to help sustain the post-war construction boom - they are a great construction tree, but not much else. (I am told that animals will not live in these forests, but only where there are deciduous trees.) In the long-term it would be better for the city if the forests were slowly returned to deciduous trees, which would then provide a better balance for sustainable use after fossil fuels become unavailable.

And that's the bottom line, really - sustainable use and management. Anything else these days is truly asking for trouble. Profits can be made from sustainable use of forests, but probably not on the scale that businesses expect. Unsustainable management of forests, however, will nearly always result in big losses, which the companies try to 'externalize'. It's time they were made to see that these things have a tendency to snap back in your face further down the line.

Stew (not verified)

Wed, 2009-04-01 02:10

Permalink

Careful harvesting would help Japanese forests, sustainability

Tony Boys

Sun, 2009-04-05 10:25

Permalink

Careful harvesting - by whom, when?

Sheila Newman

Sun, 2009-04-05 12:48

Permalink

Environment power needs to be local

Tony Boys

Sat, 2011-03-26 22:57

Permalink

Who cares for the forest?

Add comment