About Food

See also Food links.

See also Food links.

I’m not a vegan or even a vegetarian. I guess you could call me a reasonably discerning but practical omnivore but I’m becoming rather desperate to find something I can eat without feeling guilty about the harm I am doing to someone, something or to the environment.

I’m not a vegan or even a vegetarian. I guess you could call me a reasonably discerning but practical omnivore but I’m becoming rather desperate to find something I can eat without feeling guilty about the harm I am doing to someone, something or to the environment.

The other night I had salmon for dinner but my pleasure in eating it was destroyed by knowing that it is farmed in Tasmania where salmon farming is so intensive it is badly polluting the local environment and that salmon raised in crowded conditions suffer stress as do all animals forced to live in such an unnatural manner. I felt turned off by the current media about how the salmon we buy is artificially coloured pink as the fish do not eat the normal diet they would have in the wild to give them their colour but instead are expected to form their flesh from dried up wastage from the chicken industry! How can I enjoy salmon again unless I know it was caught in the wild rather than corralled and extracted from a paddock in the sea. Where do I find wild salmon? Is there enough to go around and do I need to set aside a day’s pay for one serve?

The next day for lunch I opted for an omelette made from free range eggs. But my conscience was not clear. I know the eggs labelled as such are not necessarily genuine free range. Even if they are “ free range”, I know is not free in the sense that the birds have an enjoyable life scratching around and eating a varied diet straight from the earth as do the happy hens on a friend’s tiny farmlet in a town an hour or so from Melbourne. Instead, hens producing “free range” eggs for the masses have a couple of hours per day outside and otherwise they are crowded into barns. So I could not feel 100% happy about my omelette.

What about vegetables? Well apart from the fact that the growing of vegetables for humans displaces nature on the land required I suppose I can consume with reasonable impunity. I could grow them myself but on the tiny amount of land I own and the small amount of sunshine available after the house next door and its tall hedge have stolen most of it except in summer, my supply would be extremely erratic. No, I cannot rely on that except the occasional garnish of parsley..

Aside from vegetables a vegetarian diet may include biscuits, bread and pastry all of which can transform a vegetable selection into a satisfying meal. But hold on a moment! I see from the packet that the biscuits I am about to eat contain palm oil the production of which has driven land clearing in the places it grows best. This land clearing has destroyed the habitat of one of our close relatives, the orangutan and as species , they are in peril! I can’t eat those biscuits. I’ll opt for those not containing palm oil. But all biscuits are made from grains. The production of grains for an ever growing population of humans drives land clearing and habitat loss! This is undeniable! All land taken over for agriculture must be taken from other species, be they orangutans, elephants , kangaroos, all kinds of birds reptiles, insects (including bees).

I can avoid palm oil but can I avoid grains if I am a vegetarian?

The other large category (before I get onto meat!) that is morally problematic is “dairy”. Milk, yoghurt, cheese, cream, butter all of which I love. But they are produced by animals (usually cows) that are forced to calve annually, to be separated from their babies before those babies even have the brief pleasure of suckling from their mothers. The babies (“poddy” calves) are hand fed up to the day they go market . Forlorn and abandoned they await their fate to become another delicacy that I decided long ago not indulge in – veal. I cannot eat any dairy products without thinking of the poor exploited animals who provide it to me.

What about meat from land based animals? Firstly let’s take chicken. I love it! I also love chickens. They are delightful creatures. The chickens bred for meat now look nothing like the chickens we may have known personally as children. I knew them from my grandparents' place where they happily scratched round all day after producing an egg each in the nests in their coop. My grandmother would select one to eat maybe 3 times per year so they had a dual role! Meat chickens now are lethargic and inelegant sedentary creatures displaying little curiosity. Such a creature can garner a lot of flesh on its bones quite quickly unlike the active, exploring, scratching sort of chicken we think of when we think of a chicken. I find that off-putting. For me it is a step too far into genetically engineered dinner.

The first favorite food in my life was bacon. I loved it, especially the way my mother cooked it – crisp, hot and a few ribbons of fat bordering the very tasty lean meat. I still love bacon but I have hardly eaten it at all for 20 years because of what I know about the conditions that pigs live in before they are harvested for us. It makes me very sad to see a sow’s body pressed up against a metal frame supposedly for her own good and pigs living in concrete enclosures. I would feel happy eating bacon if I knew the pig had run around and wallowed in mud during its life.

Beef- well maybe the cattle involved get the best deal. I know people who produce beef and I know they care about their animals. Perhaps their lives are acceptable til it is time to meet their maker. I would be happy to eat a porterhouse steak if I knew that the animal’s life had allowed him to express his nature, that he had felt the sun on his back and enjoyed the shade of a gum tree whilst looking at the sunset and later met a swift, unconscious end, knowing nothing about it. But when I see the way our beef cattle from the north are treated overseas, it puts me off beef full stop. I stop trusting anything about its production.

Where does this leave me ? Sushi has lost its shine, Orange Roughy is a no- no ; its life cycle is too long for a regular harvest to be sustainable. What about tuna? Well it might be Ok except that it is caught with large nets that take in other marine animals. There are also some doubts about the sustainability of this "resource", anyway.

Where do I go from here? There are problems with everything as I try to compose my menu.

The problem is that everything needs to be produced on such a large scale to fulfil the needs to humans who have spread all over the globe and increased their population from 1 billion around 1800, to now over 7 billion and rising! About 2 billion people globally are hungry or undernourished. Many in first world countries are malnourished on a diet of addictive junk foods such as fries and hamburgers and these same people may well be obese from the excessive but empty calories of their diet. As for me, I just suffer from “moral starvation”. This is not an inability to access food, but an inability to find anything I can eat with a clear conscience that is not part of a harmful industry. I suppose I could hunt for and gather my own food but there is little game or produce in the suburbs.

Hobbes’ declaration that life is “Nasty, brutish and short” is often quoted today (although , completely out of context, it was not unconditionally so) and modern economists may decry the “scarcity of resources”, but this is only one view of the world, and one that has been formed relatively recently in Western history – perhaps it is no coincidence that this attitude developed along with philosophies of self interest and social theories of “survival of the fittest” (this is no criticism of Darwin’s theories, just their misapplication to human affairs, as promoted by Herbert Spencer).

However, there is another view of the world. That is of one of abundance and bounty. The fruit tree bears far more than is needed to reproduce itself. There is almost nothing we cannot eat: many plants, the flesh of animals (also abundant in natural environments), their milk, their eggs, the sap of trees like maples, the honey of bees, the fish, crustaceans, frogs and seaweeds of the rivers and oceans, the mushrooms and fungi of the forest. It seems there is no reason for anyone to go hungry. Even less so with a little tender cultivation. In fact, it seems that mostly what is needed to prevent hunger is access to land, knowledge of plants and animals, some basic hunter gatherer skills, and protection of the natural environment.

However, we believe to improve on nature with our elaborate artificial constructions. But we what we bring to the world is mostly decay. Everything we (people) make decays, but in nature there is no decay, just transformation. The seed of grain we plant is, for all intents and purposes, eternal. Seeds reproduce themselves, not only infinitely in abundance, but infinitely through time. True, there may be slight changes by breeding and other forces, but again this is more transformation than destruction. Carrots may be larger and sweeter than they once were, but they are still carrots. Species may become extinct through external forces, but the idea that they – out of themselves – would decay and cease to reproduce is preposterous. Yet, what do we develop? Nothing less than something abhorred by nature: sterile seeds, that cannot and do not reproduce (although apparently not yet in commercial food crops).

What about human relations? Let us imagine what these could be like, in their best ideal form. What about close communities where people care for each other, share with each other and help each other out, whether incapable of providing for oneself or just plain lazy (primitive societies often provided even for these people, without question). What need then of having many children out of fear of not being cared for in your old age? Certainly people will still do selfish and stupid things, but with compassion, tolerance and understanding such problems should be easily corrected.

But what do we have instead? A system whereby people do not look after each other directly, others are paid professionally to do this (and often they are the lowest paid, a reflection of society’s values?). Instead we are freed of concern for our fellow man, beyond our own immediate families, as our fellow man is free from us. We are all encouraged to pursue our own self interest, to take gains and advantages wherever we can get them, and to consider such gains exclusively your own. Is it no wonder that nature has thus been divided up, owned in effect by a few through their agents – their corporations (the most impersonal construct imaginable) - and this fiercely defended against the claims of those who have less or nothing? What sort of a ‘society’ has this resulted in anyway? A world where one half has too much food and the other half starves. Can it really be called ‘human’? Or would ‘inhuman’ be more apt?

Do our sporting endeavours reflect our social attitudes? Now I am not entirely against team sports, but perhaps there are some elements of this that need consideration. A friendly game seems to do no harm, particularly where the teams are somewhat arbitrarily composed, and the game is played mostly for the pleasure of playing. But where one side goes out with a determination not so much to enjoy the challenges of the game, but focused on the defeat of another team – even more so when their career and salary depend on success - then this is perhaps a reflection of deeper and darker social constructs. Particularly when you have vast numbers of followers, who are not players, but gather largely based around a kind of tribalism, perhaps again as a form of protection in a hostile world, through some sense of a shared group identity? But perhaps also deriving some pleasure from the power and prowess demonstrated by players over others? Or perhaps to share in their glory? Team sports on the scale we have today seem to be a recent phenomenon in Western culture, coinciding with industrialism and its ideals.

Yet, there are two sides to sport. On one side is team sports, where one team vanquishes another. The other side to sport – a side that featured prominently in ancient Greece - is individual sports, such as discus, which were perhaps more about individuals seeking perfection. In such a situation individualism is appropriate as such perfection need not come at the expense of another, but rather mastery of oneself (self discipline) and one’s body. Such individualism restricts nobody in how perfect they can become, and all who wish to participate can achieve a high level of perfection.

In fact, this may give a hint as to where society has really gone wrong. Rather than focussing people on the perfection of themselves – as caring individuals, who do not act selfishly and who share and care for others - our society has gone the other way. People are encouraged to give in to their most selfish and gluttonish tendencies, to be the greatest, to not put others before themselves, but themselves before others. This is a far easier path to walk, as it requires no self-discipline. But as only few can succeed at this game of ‘who is greatest’, the vast majority of the people will be disappointed, and possibly depressed. Others, who suspect deep down that the game is not worth playing, may end up not only entirely confused by the behaviours around them, but also misunderstood.

It seems Hobbes also understood this inclination as he declared:

But is it really the nature of man to be so? Or can we be - or at least aspire to be - better than this?

Abstract (Part of the original paper; useful, so I'll leave it here.)

This paper attempts to map out a definitive route to human “happiness” based on the notion of a human reconnection with nature through an appropriate heart-brain balance. The consequences of this for human society, especially agriculture, are explored. The content focuses specifically on Japan, but is thought to be adaptable to any society in the world.

Fully referenced PDF file of this article (Depending on your computer, you may also be able to see the Japanese 'kanji' used in the section on Shinto.)

Introduction

Current Japanese society cannot be said to be very “happy,” nor does it appear that “happiness” will be achieved in this society, or in other advanced industrial nations, simply by continuing along the lines of the present economic and social policies. The GDH (Greater Domestic Happiness) and Food Problem Research Group was set up by the Mottainai Society chairman, Professor Yoshinori Ishii to look into the future of Japanese society in the context of ‘Peak Oil’ and to address the possibilities for the achievement of “happiness” in Japan. The research group held its first meeting in Tokyo on 17 November 2009. Prior to the meeting, the secretary of the group, Mr Yasuo Tamura, circulated the following memo.

---------------

1 Nov. 2009

Reason for the Establishment of the “GDH and Food Problem Research Group”

The oil peak has already come and gone and the natural gas and coal peaks are expected within the next 15 years. Nuclear power cannot do everything. It is high time to begin putting together a plan for a transition from an oil-dependent “high-energy society” to a “low-energy society.”

The basics of civilization – transportation, fuel, chemical raw materials, etc. – are about to undergo a fundamental change. Globalization will also recede. It will be necessary to plan for regional decentralization, local production for local consumption, environmental coexistence, and localization.

That means not making GDP the target for the state and society. That is because growthism and the society based on the competitive principle have not made people happy.

We wish to outline a concept for a society that values the concepts of mottainai (‘waste not, want not’) and sufficiency, that values the bonds between people, and that cares for life and the diversity of nature. For this, we think in terms not of GDP, but GDH – Gross Domestic Happiness – and will also undertake a transformation of the way in which we think about the food issue. That is the “GDH and Food Problem Research Group.” We hope that you (the prospective members of the research group) will approve of these ideas.

---------------

The necessity to replace GDP/GNP, symbolizing growthism and a society based on the principle of competition, with a more human society oriented towards caring for life and nature was at the time, and still is, becoming clearer by the day. This group took as its starting point “Gross Domestic Happiness” (GDH or Gross National Happiness, GNH) as proposed by the King of Bhutan and implemented in that country.

At this stage, the central emphasis of the work of the group was less on defining what “happiness” might be than on examining Japan’s food issues. The feeling was that most of this work on the social realization of “happiness” had already been carried out by the King of Bhutan and his advisers in devising the Bhutan GDH and that once society took on the GDH approach and the food issue was resolved, then Japan’s society would realize happiness as a matter of course. However, while work and discussions on the issues of food, energy, employment, social change and Japan’s future progressed, it proved more and more difficult to get a firm grasp on the concept of “happiness.” As this was happening, I was beginning to read around the subject of human happiness a little more and increasingly came to feel that “happiness” relied on an appropriate human relationship with nature as much as it did on appropriate human social and economic relationships. If that were so, then however much we ‘adjusted’ human relationships in the attempt to bring about human happiness in society, unless the human-nature relationship was also ‘adjusted’ so that all people lived in harmony (more or less) with nature, then “happiness” would be an illusion, and therefore unattainable. The development of these ideas in the context of Japan’s food and energy issues is the content of the remainder of this paper.

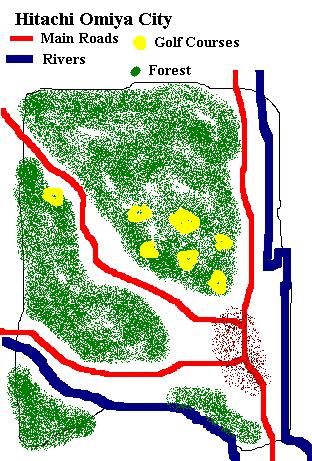

Part 1: Japan’s Food and Energy Problem

Japan’s food issue is inseparable from the world food and energy situation. Japan imports roughly 60% of its food calories. The population of Japan, roughly 127,700,000 and falling very slowly, lives on a land area of 377,944 km2, of which around 65% is forested mountain land, and has roughly 4.5 million ha (45,000 km2) of farmland. That calculates to 0.035 hectares per person (ha/cap) or about 28.4 cap/ha. Good Japanese farming will support about 11 cap/ha, thus showing why it is that Japan can feed only about 40% of its people. This need to import food is likely to become critical as fossil energy resources become more expensive and less easily available in the second and third decades of the 21st century. The reason for this is that a great proportion of agriculture around the world today, especially that in industrialized countries and the countries that are exporting large amounts of food to Japan (the USA, Canada, Australia, Argentina, and to a certain extent Thailand) relies heavily on fossil resources to produce food. The international transportation of food is also heavily reliant on fossil energy resources.

The main uses of fossil resources in agriculture are in chemical fertilizers and other agrichemicals, fuel for machines and transportation (and the energy required to manufacture machines), and the generation of electricity for pumps, dryers and so on. Higher prices or reduced availability for fossil fuels means a reduced ability to fertilize cropland, protect crops from weeds or pests, to use machinery to cultivate the land or process crops, and to move materials from one place to another. The ability of current food exporting countries to export will also be diminished, it will become difficult to transport large amounts of food over long distances, and at the same time it will also become more difficult for Japan to maintain its current level of food production. A simple simulation devised by the author shows that with all current conditions except for energy use remaining the same as they were in 2009, but with fossil energy use in Japanese agriculture declining suddenly to zero, the current food self-sufficiency of Japan, 39-40%, would decline to 15-16%. Thus, in a generalized world fossil energy shortage Japan is likely to face simultaneous drastic reductions in both food imports and its ability to produce food. It was generally recognized in the research group that this situation is likely to occur before 2030, and could happen at anytime from around the middle of the second decade of the 21st century.

If a situation of a sudden cessation of all food and energy imports into Japan were to occur, this would bring about a human catastrophe on a massive scale. However, the food and energy import problems are unlikely to happen both simultaneously and suddenly, and since there is perhaps at least five years (as time of writing, October 2011) before any serious crisis occurs, there are a number of measures that the Japanese people and government can start to enforce now to avoid, as far as possible, this deep human catastrophe from becoming a reality. In brief, the following measures can be taken:

1. Reduce reliance on chemical fertilizers and other chemicals and move slowly towards sustainable farming systems based on organic materials (organic farming, permaculture, natural farming, mixed farming, LISA [low input sustainable farming], and so on).

2. Increase farmland area up to 5.3 million ha and improve the cropping ratio up to 140%, while at the same time providing greater (financial, government support) incentives to farmers to produce food by making it possible for them to make a decent living from farming, obtain expert help in the transition to organic forms of agriculture, and increased security in the form of, for example, crop insurance.

3. Increase the number of people working in farming (especially young people) from the approximately 2.5 million now up to 10 million, again by making it worth people’s time to farm in financial terms.

4. Begin to provide farm draft animals to replace machinery for the time when fuel becomes unavailable. Introduce a target of breeding two to three million farm animals (horses, oxen, etc.) by 2040.

5. Ensure the sustainable management of all forests for the sustainable harvesting of wood for construction and energy, and the harvesting of other forest products, such as leaf humus for fertilization of farmland.

6. Produce biofuels (without competing with the production of food for humans) for running farm and transport machinery over the next 20 to 30 years.

7. Reduce the need for the transportation of food and enforce, as far as possible, local production for local consumption.

8. Reduce food processing and packaging to the minimum necessary.

9. Rethink food retailing and preparation (including restaurants) in order to use less energy.

These are all worthwhile policies that can be introduced locally and gradually. However, as of time of writing (October 2011), not only are no such policies being implemented, they are not even being considered. Since it takes at least several years for farming practices to change, agricultural policy needs to be thought out ahead of time, not when the crisis is beginning to happen.

Further, the events following the earthquake and tsunami disaster of 11 March 2011 have made the situation considerably worse. Substantial areas of Fukushima Prefecture have become uncultivable due to radiation pollution of the land. The fear of radiation pollution of food will also drive some consumers away from domestic food produce to imported foods. These two factors will tend to exert a downward pressure on Japan’s food self-sufficiency.

Japan is now also preparing to join the TPP, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free-trade economic partnership that will likely include many countries in the Asia-Pacific region, such as the USA, Australia, New Zealand, Peru, Chile, Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam and others. The abolition of import tariffs on agricultural products will mean an influx of cheap food from exporting countries and a loss of domestic markets for Japan’s farmers. The Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) has estimated that Japan’s food self-sufficiency will fall to 13% if Japan joins the TPP. This is tantamount to a destruction of Japan’s agriculture and rural economy at precisely the time when Japan should be devising policies to protect and bolster these against future worldwide food and energy shortages.

If the worst does come to the worst and Japan’s food (and energy) imports cease, how far can Japan go in providing food for its population? A useful study by Toshiki Mashimo estimates that if producers do their very best to expand production and consumers do their very best to adjust consumption to lower levels and to traditional foods, Japan might be able to raise its food self-sufficiency to 80% under current agricultural methods, or to 75% if organic farming was the main method of production. This will not be easily achieved, but if it is, and food and energy imports can be maintained at a certain level, this kind of effort would be a great relief to the Japanese people. At the same time, it suggests that the Japanese population needs to decline to 80% or 75% of its current level, or about 95 to 100 million people rather than the current 127.7 million. At the current slow decline of the Japanese population, this situation is not likely to be achieved until 2050 or later.

A food shortage, perhaps triggered by a fossil energy crisis, is not going to contribute to the “happiness” of Japanese people. I will explain below that “happiness” is not something that is going to be easily or quickly achieved in Japan (or in any industrial country). I hope it will become clear how this “happiness” is related to agriculture as the argument is developed.

Part 2: What is “Happiness” and how can it be achieved?

2.1 Introduction to “Happiness”

Since I believe that nearly all previous attempts at defining “happiness” have been wide of the mark, I do not intend to review past literature on the subject. The reader may enter the phrase “definition of happiness” into the search box in Google to find sufficient examples of this definition and other related information. I currently use the following definition:

A long-lasting sense of inner contentment and security.

I think this covers the main aspects of what is generally thought of as “happiness.” One problem with this definition is that it gives us no clue as to how “happiness” is to be achieved.

So how can this “happiness” be achieved? Let us try to list up a number of factors that might help lead to the achievement of “happiness” in a society.

1. At least sufficient material conditions for a “decent” level of daily existence (food, water, clothing, shelter, and so on).

2. An even distribution of the materials in 1., or at least a sufficiently “fair” distribution that does not cause a part of the population to feel that it is being treated unfairly.

3. 2. infers that human relations within the society will be “good,” i.e. that people are “fair” with each other and that no one is being mistreated. This would also imply the absence of wars and other forms of violence.

Human security is sometimes said to be composed of the two human freedoms of “freedom from want” and “freedom from fear”. Human security might thus nicely sum up the factors 1. to 3.

However, for our “happy” society, we might also want to include fair access to “decent work,” good quality health and education, as well as a number of freedoms (freedom of movement, freedom of choice of occupation, freedom of expression, freedom of association, etc.) that are now supposed to be guaranteed under UN covenants. A similar list of factors can be seen in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which also includes love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualization.

Thus the factors that might aid in the creation of a “happy” society are well-known. The assumption then is that the “happy” society may be approached by implementing social policies that lead to the realization of these factors in society; a social engineering approach to “happiness.” Unfortunately, although the material conditions of the 20th century might have enabled this to happen, it is most definitely what did not happen in almost all societies. In fact, as we are noting recently, the more materially affluent societies become the more difficult it appears to be for those societies to be “happy” - to be inhabited by people who consider themselves to be “happy.”

So what is the problem? Firstly, I think that if we wish to discover what human “happiness” might be, although material (and psychological) conditions are necessary they are not sufficient, and that instead of looking for factors external to the human being we have to look at internal factors. That is, we have to look at what human beings are, what we have evolved to be, in order to find where our “real happiness” lies. Secondly, as I have already mentioned in the Introduction, I have become convinced that “happiness” depends on having an appropriate relationship with nature. Despite the over-simplicity of the idea, the more tenuous the human relationship with nature becomes, the less likely we are to achieve “happiness.” (I suppose it’s necessary to define “nature” here, but basically I mean non-urbanized areas where people can come into contact with wild or domesticated animals and plants, including most agricultural settings, coastal areas, wilderness areas, forests, and some desert areas.) I hope it will become clear later why these two factors (what we are and our relationship with ‘nature’) are, in fact, so deeply connected as to be virtually one and the same thing.

2.2 Carlos Castaneda - his contribution and his failure

A surprising number of people have never heard of Carlos Castaneda (abbreviated hereafter to “CC”), but if you were an English-speaking young adult in the 1970s it may have been hard not to have heard of him. CC’s first book, The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge, was first published in 1968, when CC was a student of anthropology at UCLA. The book describes how CC met and became an apprentice to a Yaqui indian shaman, don Juan Matus. ‘Teachings’ reads as a diary of the apprenticeship CC underwent with don Juan and was considered at the time to be a masterpiece of anthropological research. (CCs third book, Journey to Ixtlan, is almost identical to the Ph.D. dissertation that CC submitted to UCLA in 1973.)

Through don Juan, CC comes to see that there is “a separate reality” (the title of CC’s second book), a separate awareness or a separate consciousness from the one that we usually experience in our daily lives. This offers the possibility of, if not the realization of “happiness,” a totally different way of life based on the cognitive structure of the shamanistic world of don Juan. To the American youth of the early 70s, who were in the midst of experiencing or who had recent memories of the assassination of President Kennedy, the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, the hippie movement, Watergate, and the deaths of Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison and Janis Joplin, the notion of a way out into a different way of life and a different world was appealing indeed, and CC’s books sold extremely well.

So if this is not a path to “happiness” (a different way of life, but not necessarily to “happiness,” as can be seen from the books themselves), then why are we mentioning this here? The interesting thing about don Juan’s different perceptual mode is that the skill that must be mastered in order to gain the new perceptual ability is stopping the internal dialog. It is necessary to stop the internal chatter in your brain, the endless conversation that we have with ourselves nearly all our waking hours. Everything in don Juan’s shamanistic perceptual mode begins with emptying the brain of this internal conversation.

This should come as no surprise to South and East Asian Buddhists, who are all familiar with Zen Buddhism. The main practice of Zen is Zen meditation (zazen, sitting meditation), the purpose of which is to quieten the mind and stop the inner dialog. In the Flower Sermon, the Buddha is said to have uttered the following words to explain what he was doing while looking at a flower:

I possess the true Dharma eye, the marvellous mind of Nirvana, the true form of the formless, the subtle Dharma gate that does not rest on words or letters but is a special transmission outside of the scriptures.

I think this is exactly what don Juan was trying to teach CC. The separate reality that was reachable if one was successful in stopping the internal dialog was termed by don Juan the “nagual.” By contrast, our ordinary, everyday perceptual mode was termed the “tonal.” (The term “nagual” is originally from the Nahuatl word meaning a shaman, but in CC’s books is used in the sense of a tonal/nagual dichotomy.)

Don Juan explains that “A warrior is aware that the world will change as soon as he stops talking to himself,” but just exactly what is involved in this change? CC’s fourth book, Tales of Power, consists almost entirely of an explanation of the tonal/nagual contrast and the notion that, if one can attain the nagual, this will make it possible for a person to see things differently, as opposed to the ordinary ‘seeing’ of objects that we do in our normal mode of perception, the tonal. On pages 125-126 of Tales of Power, in a chapter entitled “The Island of the Tonal,” don Juan explains to CC, while out eating a meal, that the tonal is like the tops of the tables in the restaurant. Everything that we can talk and think about in our normal mode of perception is on the tables (representing the minds of different people). Even ‘God’ is on the table, as it is something we have a word for and can refer to. Don Juan likens God to the tablecloth that can wrap up everything else on the table inside itself. The nagual, then, is the space between the tables; the area where we do not use words to comprehend or communicate what we see there. (So if we have a word for ‘nagual,’ isn’t it part of the tonal? No, don Juan says, because the tonal/nagual are a true pair.)

The above describes for us a door into ‘a separate reality,’ but this seems to lead neither to nature nor to happiness. Moreover, in the mid-70s a number of people denounced CC’s work as a hoax and cast doubts as to whether don Juan actually existed as a real person. Primary among the detractors was Richard De Mille (son of the well-known film director Cecil B. De Mille), who showed that it was more likely that CC got his ideas by spending his days in the UCLA library than out in the desert of northern Mexico with a Yaqui shaman named don Juan. (His 1980 book, The don Juan Papers includes a 47-page glossary of quotations from don Juan and their sources, which include Wittenstein, C.S. Lewis and Yogi Ramacharaka, a pseudonym of William Walker Atkinson).

This would suggest that CC himself was never actually able to stop his inner dialog, find the nagual and see. However, he had spent at least ten years reading about and discussing transcendentalism and the occult. He knew enough about these subjects and had sufficient talent as a writer (in English despite the fact that he was a native Spanish speaker) to concoct a ‘story’ that was convincing enough to satisfy even UCLA professors. Today, his books, which are now thought to have sold over 10 million copies, are generally considered to be novels (though they are still marketed as ‘nonfiction’). Even if they are novels and CC himself had no direct experience of the nagual, his sources appear to have been largely valid. His enormous influence has, therefore, opened the eyes of a generation of English-speakers to the idea of reaching ‘a separate reality’ by shutting off the inner dialog. That has been CC’s lasting contribution.

We may now imagine millions of mostly young people attempting to stop their inner dialogs and reach a different mode of perception, with varying degrees of success. Some may have been successful, but the general feeling is that although CCs books were fascinating to read, they were an incomplete ‘manual’ for reaching the nagual. There are clearly still elements missing here, and I think these are the link with nature and one further factor that is the main subject of the remainder of this paper.

2.3 How do humans connect with nature?

How does stopping the internal dialog have a relation to the human being’s ability to form a relationship with “nature”? The answer is: by perceiving “nature” with the human heart.

Most people are aware that the heart is an organ that pumps blood around the body. Far fewer people, however, know that the heart also has other functions and abilities. These include:

1. High sensitivity to electric charges, electromagnetic radiation and magnetic fields,

2. An ability to transmit electromagnetic radiation. The heart also has its own magnetic field,

3. Being a ‘brain’ in its own right, since 15% to 20% of its cells are neural cells.

Many of the electromagnetic signals living organisms receive contain large amounts of information. Living organisms are able to decode the information embedded in those signals and respond, since we are all transmitters as well as receivers and communication always goes both ways. Groups of cells in the heart, as in other organs, beat together at a single frequency. This synchronization of cells in proximity with each other is termed entrainment.

A heart is, in fact, a large self-organized grouping of cells.

This aggregating of cells, as with electrical detection arrays in fish, makes it possible for the organ to sense extremely weak electric fields. Furthermore, the role of magnetic fields in cells and living organisms should also not be overlooked.

Cells and living organisms not only perceive, decode, and respond to extremely weak electric signals, they perceive, decode, and respond to magnetic signals, which contain information, just as electric signals do. The organ of the human body that is very sensitive to magnetic fields is the hippocampus, an organ that works closely with the heart and “works closely with the amygdala … to modify body physiology in response to emotions.” The hippocampus is also involved in “the extraction of meaning from the vast sea of signals in which we live,” just as salmon, bees and birds “orient themselves within directional meaning.” The hippocampus can also form new neurons in response to demands to process nonlinear information from the environment, if you live in a rich and stimulating environment where you are continually receiving such electrical or magnetic signals.

We are made to be in the wild nonlinearity of the world, and this immersion is needed for the hippocampus and our central nervous system to be healthy.

Since all living organisms both receive, decode, and respond to electrical and magnetic signals, this means they are capable of communicating with each other. This is automatic; we have evolved with it, just with all the other bodily functions, and with the five senses. Furthermore,

… the human heart is vastly more than a muscular pump – it is one of the most powerful electromagnetic generators and receivers known. It is, in fact, a highly evolved organ of perception and communication.

Buhner says that “the magnetic field produced by the heart … extends around the body in a torus, a fractal, sort-of-spherical shape that continually flows through space,” and that “Measured with magnetic field meters, the electromagnetic field that the heart produces is some five thousand times more powerful than that created by the brain.” This might explain how, if some people are actually capable of seeing electromagnetic fields, people report seeing the ‘aura’ of the human body shaped like a luminous egg. This is how CC reports that don Juan sees humans, but it is suggested by Richard De Mille that CC obtained this idea from William Walker Atkinson while reading in the UCLA library.

Nevertheless, if we live in an environment that is filled with electrical and magnetic ‘pollution’ and in a culture that de-emphasizes the nonlinear sensitivity of the heart to the benefit of the linear and analytical brain, this ability to perceive and communicate may atrophy. Nature is, in fact, a “web of communications that is so complex and detailed that there is no way to understand it with the linear, analytical mind,” which is a very similar situation to the tonal/nagual contrast of Carlos Castaneda. If we have lost the ability to connect with nature through the heart, perhaps we should think about trying to reconnect ourselves.

2.4 Is it possible to ‘reconnect with nature’?

The quick answer to this question is ‘yes, of course,’ but it depends on your past history (the degree to which the linear/verbal/analytic mode of cognition has colonized your ‘mind’) and your age (the older you are, the more difficulty you will tend to experience when attempting to ‘reconnect’).

Just as heart cells in proximity to one another ‘entrain’ (their oscillations synchronize), so when the electromagnetic fields of two hearts are in proximity with each other they will also entrain. Not only two human hearts, but this will occur when the electromagnetic field of the heart is in contact with that of any other organism. At that point, “there is an extremely rapid and complex interchange of information.” This incoming information perceived by the heart may be experienced as ‘emotion,’ and the meanings embedded in the information can be extracted from the emotional flow just as meanings are extracted from the sounds we hear. However, we are trained to ignore these sensory cues; most people are unable to consciously use the heart as an organ of perception and the information perceived by the heart is processed below conscious levels of cognition.

There is nothing strange about this. It is well-known that humans are affected by olfactory, visual and auditory signals that are not processed consciously and that different people are capable of different levels of olfactory, visual and auditory perception. What may be strange is that our society (the modern, industrialized lifestyle) actually trains people to ignore these sensory cues and, through education, attempts to colonize the mind with linear/verbal/analytic/reductionist styles of cognition. Overcoming this bias is not easy, but because it is the evolutionary birthright of every human to have and use these abilities, it can be done. It is especially easy to train children to use both their brains and their hearts in tandem. (I am not suggesting that people ‘turn off’ their brains and perceive solely with the heart!)

Let me offer two further pieces of ‘evidence’ that hint at the heart being an organ of human perception. The first is what we call “love” or “falling in love.” Human language is full of the connection between the emotions, especially “love,” and the heart. A “sweetheart,” a “broken heart,” “heartstrings,” “heartache,” and so on are simple examples. The almost ubiquitous use and recognition of the ‘heart mark’ are also symbolic of this. “Love” has also been described as a kind of “madness” by Shakespeare and others. However, if we were to see “falling in love” as the entrainment of two hearts that took a liking to one another (as well as the two people involved being aware of other sensory cues), we might not be quite so inclined to see “love” as a kind of madness. To the calculating, analytical brain, “love” surely is madness; it literally drives the brain mad not to be able to make sense of what the heart is doing perfectly “naturally”!

One further clue is from the Greek word aisthesis, which Buhner states is the “heart’s ability to perceive meaning from the world.” Definitions of this word are generally not clear about the function of the heart. A definition easily available on the Internet states that aisthesis is a “sensation, perception, as an opposite of intellection (noesis), understanding and pure thought; more loosely – any awareness.” Hillman, however, says that, “In Aristotelian psychology, the organ of aesthesis is the heart; passages from all the sense organs run to it; there the soul is ‘set on fire.’ Its thought is innately aesthetic and sensately linked with the world.” It seems to be clear that the Greeks had no problem about perceiving with the heart.

So, all we have to do is practice perceiving with the heart. Yes, but if you have never actually been aware of doing it before, just exactly how are you going to go about doing that? In his book, The Secret Teachings of Plants, Buhner gives ten “exercises for refining the heart as an organ of perception,” and I would recommend anyone interested to try doing these exercises. However, I think the basic thing that anyone can do is to find good natural areas, such as woods or forests or mountain areas that they like and spend time there. Not everyone can do this, especially if they are living in a large metropolis, so there is an immediate ‘lifestyle’ barrier to ‘reconnection.’ But assuming you are able to spend time in a natural environment, what then?

Buhner, being interested in plants, asks us, “… if you truly want to communicate with plants, just what is the status of the plant? Just how do you really feel about it?” Plants have been on the planet longer than we have, but do you see them as your equal, or even superior to you, as if they were our elders or teachers? Buhner suggests that if you do not, the plants will not ‘talk’ to you. Knowing the name of a flower or tree will not help you. These anthropocentric words are part of the linear world, not part of the nonlinear world of heart perception. The tonal/nagual dichotomy again, if you like. First you must try to stop the internal dialog, halt the flow of words and be prepared to abandon your accumulated linear mode knowledge – to know nothing. That may be as simple as just breathing a little more deeply than usual and then standing or sitting in a relaxed way, taking in your surroundings by ‘feeling’ them rather than thinking about (appraising, explaining) what you feel in terms of verbal thought.

Preconceptions must be abandoned. There is nothing in the linear/verbal/analytical/reductionist world that has prepared you for this mode of communication. There are no neat formulaic rules for this – you will be outside of human culture and must be prepared to allow anything to happen and be prepared to surrender yourself to it. Otherwise you will probably experience nothing and get nowhere with it. Only those who are not afraid to step outside of our current culture of linear cognition will be able to, gradually, step into the nonlinear perceptual mode of nature.

It is important to see, hear and smell what is there in front of you, in nature, and pay attention to that rather than what your brain is trying to tell you about it. This does not simply mean “shutting off the inner dialog.” Buhner tells us that we cannot stop the linear mind and leave nothing in its place. The answer is to do something else instead; sense what is actually there in your surroundings. If you find yourself being drawn to a plant, go up to it and spend some time with it. Touch it and taste it. Try to be aware of its scents. You may feel embarrassed about doing this. If you try to taste a small part of a leaf, you may hear voices in your mind (your parents, former teachers and so on) telling you not to do so. It may take you some time to get used to overriding these voices. Buhner quotes Henry David Thoreau, who said, “Nature is a prairie for outlaws,” and tells us that “the green is poisonous to civilization.” Civilization’s rules are not enforced in nature, and we should understand that a “reconnection” with nature will change us, and make us more “natural” and “wild.” But humankind really (from the point of view of October 2011) needs to change in this way now if we are to step back from the catastrophes an over-emphasis on linear/verbal/analytical/reductionist cognition has caused us to wreak upon ourselves. This is one way to return to what evolution has intended us to be – to reclaim our birthright.

Once you have a relationship with a certain plant, and while this may happen quite quickly, it may also take weeks or months, as your heart’s electromagnetic field begins to entrain with that of the plant, you may notice a certain ‘emotional tone’ arising within you. In the same way as you suddenly become aware of the picture embedded in an ‘optical illusion’ puzzle, you may then receive a sudden communicative burst from the plant, termed by Goethe “the pregnant point,” that can be routed from the heart to the brain and become accessible to linear/verbal/intellectual/analytical cognition. This is the first real communication with the plant. Buhner describes in great detail how this relationship with this and other plants can be developed in order to receive direct knowledge from plants about their medicinal properties for humans. However, I shall stop here, since the aim of this short paper is not to help you to become a shaman herbalist but simply to show how human “happiness” can be achieved through a ‘reconnection to nature.’

3. Further comments on aspects of “happiness” and ‘reconnecting with nature’

Having read this far, many may perhaps feel that what the arguments I have presented here are somehow not ‘real,’ belong in the realm of ‘religion,’ the ‘supernatural’ or the ‘occult.’ Here, I would like to present further evidence to show that the idea of the human connection with nature (in a wide sense, to include not just individual plants or animals, but also a wider ‘natural consciousness’ from the ‘interacting web of life’ or even the cosmos) through perception using the human heart is a ‘real’ phenomenon close to our daily lives. I will also end the paper with comments on what the consequences and benefits may be for a human society or civilization that aims for an appropriate heart-brain balance, and how this implies the achievement of human “happiness.” Finally, I will make a few comments on the consequences of this on agriculture and the production of food, and how, concretely, the society of the future is likely to be shaped by putting these ideas into practice.

3.1 Do we know anyone who is doing this? Who are they and what kind of people are they?

Everyone, including lifelong city-dwellers are perceiving with the heart. It is part of who we are. Regardless of how conscious we are of doing it, it is said that experience of the world is perceived by the heart first and then flows to the brain for further processing. It is very likely that we all know people who are adept at communicating with plants or animals through the heart, but these people are more likely to be conspicuous in the countryside than in the city, and even then the person involved may not be exactly aware of what they are feeling or doing. Some may even hide their ability, since there are parts of society who do not appreciate the abilities of people to perceive nature directly with their hearts.

There are also well-known people who have been known to have the capacity to receive direct knowledge from ‘nature.’ Buhner mentions Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Luther Burbank, George Washington Carver, Masanobu Fukuoka, Henry David Thoreau, Buckminster Fuller, Barbara McClintock, and although not mentioned by Buhner, I feel sure that Rudolf Steiner must also have had a great ability to perceive the world directly through the heart. Steiner’s works are not based on linear/analytic/intellectual ‘scientific’ logic. For example, in his lectures on agriculture, which now form the basis of the biodynamic farming movement, Steiner states:

Now let us take the manure, in whatever form is available, stuff it into a cow horn and bury it in the ground at a certain depth – I would say between ¾ and 1½ meters, provided the soil beneath is neither too clayey nor too sandy. We should select a good soil that’s not too sandy. You see, by burying the cow horn with the manure in it, we preserve in the horn the etheric and astral forces that the horn was accustomed to reflect when it was on the cow. Because the cow is now outwardly surrounded by the Earth, all the Earth’s etherizing and astralizing rays stream into its inner cavity. The manure inside the horn attracts these forces and is inwardly enlivened by them. If the horn is buried for the entire winter – the season when the Earth is most inwardly alive – all this life will be preserved in the manure, turning the contents of the horn into an extremely concentrated, enlivening and fertilizing force.

These ideas were not reached through scientific experimentation, as we know that “He [Steiner] encouraged his listeners to verify his suggestions empirically, as he had not yet done.” Biodynamic farming practitioners are still doing this, as I have personally witnessed on a biodynamic farm in Kyushu. How Steiner could have ‘known’ all this is a complete mystery until we understand that he could have received the ‘information’ through the heart’s direct perception and communication with nature.

I’m not saying that we will all be geniuses of the stature of Goethe and Steiner or farmers with the unique insights of Luther Burbank or Masanobu Fukuoka if only we will learn to perceive nature with our hearts, but we will never even begin to understand what they did or how they did it unless we try to re-balance the linear/verbal/analytic mode of thinking of the brain with the nonlinear/nonverbal/intuitive mode of perception of the heart.

Indigenous people, naturally, have never lost the automatic ability to perceive directly with the heart. Buhner states, “All ancient and indigenous people said that they learned the uses of plants as medicines from the plants themselves. They insisted that they did not rely on the analytical capacities of the brain for this nor use the technique of trial and error. Instead, they said it was from the heart of the world, from the plants themselves, that this knowledge came.”

Among widely diverse nonindustrial cultures the members whose speciality was plant medicines, vegitalistas, described their experiences remarkably similarly irrespective of culture, continent or time. The vast majority (essentially all instances where I have found first-hand accounts) told interviewers that they did not obtain their knowledge of plant medicines from the exercise of reason or through trial and error. They were uniformly consistent in saying that their personal and cultural knowledge of the medicinal actions of plants came from “nonordinary” experiences, specifically: dreams, visions, direct communications from the plant, or sacred beings.

Communication with plants via the human heart also means that plants know something about the humans they are in contact with. The Pgaz K’Nyau (Karen), an indigenous people of Eastern Burma and Northern Thailand, have this to say:

Pgaz K’Nyau people have a very clear reason for honesty and purity in life and in dealings with other people. If you want to think we’re naïve, that’s up to you, but we believe that nature has a spirit. We rely on her for maintenance of our lives, and we must respect her, stand in awe of her, and obey her and act towards her with honesty and purity. It is this relationship with the natural world that has trained the spirit of the Pgaz K’Nyau people to use natural resources with great care. It also means, for example, that a man or woman who is a liar, or a thief, or is in some other way an immoral person will not be able to produce enough food. He or she cannot be a good farmer because nature will deny him or her the benefit of her miraculous power to keep us alive with food.

The Pgaz K’Nyau also say that if you want to learn from those who know about medicinal plants, you have to be apprenticed to such a person and be trained by them. In general, it is no good just following the person around and then mechanically copying what they do (unless the apprentice is extremely perceptive) because the medicines produced may not work, or may not be as effective as when the ‘knowledgeable person’ gathered and prepared them. Buhner also notes that an experienced herbalist can put out a call to a plant before he or she goes to gather it. The plant will then “begin altering the chemicals they produce in anticipation of your gathering them as medicines.” It is crucial, however, that this call has “emotional reality.” You cannot fake it.

I think you can see that this leads us into some very tricky territory. Buhner says that people who engage in perceiving nature with the heart find that a certain moral development occurs within them. This is a morality that comes out of aisthesis. “True morality begins to emerge of itself.”

Because nature does not lie, the direct perception of Nature means that each of us that does lie, each part of us that lies, even in our deep unconscious, must reorder, must restructure, if we truly want to perceive deeply into Nature.

Thus perceiving nature with the heart is associated with a certain morality. Plants (and animals) can perceive who you are and will not deal with you if they do not “like” you. As a sidelight, I will mention the story of a well-known lie-detector examiner, Cleve Backster, in 1966. A polygraph lie-detector usually consists of a galvanometer coupled with a Wheatstone bridge, and this can measure the human body’s electrical potential as it fluctuates under the stimulus of thought and emotion. One morning, Backster decided to attach the electrodes of a lie detector to a Dracaena massangeana plant in his office and see what would happen if he gave it some water. Instead of indicating a reduction in resistance, as you would expect if the moisture of the leaf increased, the opposite reading was seen as the pen on the graph paper indicated a reaction “very similar to that of a human being experiencing an emotional stimulus of short duration.” Backster figured that since the most effective way to get a quick emotional reaction from a human is to threaten his or her well-being, he would try to burn the leaf, but the instant he conjured up the image of the flame in his mind, and before he could even move, there was a dramatic movement of the pen on the graph paper. The plant had ‘read’ Backster’s mind!

Backster spent the next several years experimenting with plants. An interesting phenomenon that Backster noted was that when threatened with danger plants will go into a trance-like state, rather like a person fainting when faced with overpoweringly life-threatening situation. When a Canadian physiologist visited Backster in his lab one day, Backster was unable to get any reaction from the first five plants he tried. Backster asked the physiologist, “Does any part of your work involve harming plants?” “Yes,” the physiologist replied. “I terminate the plants I work with. I put them in an oven and roast them to obtain their dry weight for my analysis.” A short while after the physiologist left the lab, all of Backster’s plants began to respond as normal. Backster, however, was never able to discover that the key to the connection between humans and plants was the functioning of the human heart, as we have seen here.

If there is a moral dimension to the perception of nature by the heart, what of the linear/verbal/analytic brain?

Unlike the heart, with its connected empathetic connections the brain has no inherent moral nature. The continual training of children in a system of perception that is amoral leads to behaviours in adults that have no moral basis.

Buhner also quotes Masanobu Fukuoka as saying:

Nature is both the creator of man and his greatest teacher. Sensitivity, reason, and understanding true to man all can be manifested only through sympathy with nature. Judgement and criteria for right and wrong, virtue and evil, excellence and mediocrity, beauty and ugliness, love and hate do not hold if man steps off the Great Way pointed out by nature.

In other words, Fukuoka believed that if we are not connected to nature through the heart we have no basis for making value judgements. It does very much look as if the unbalance between the use of the linear/verbal/analytic mode of cognition and the nonlinear/nonverbal/intuitive perception of the heart has brought the modern world to where it is today. Is there really any option for mankind but to reappraise the contents of our civilization, the way society is run, and how we educate our children? I will have more to say about this later.

3.2 Is this ‘religion’? Where is ‘God’?

I am not going to write a treatise on religion, but simply repeat here what a few people have said because it makes sense to me. From the above, we see that the heart is capable of connecting with ‘nature,’ especially individual plants and animals, but there also seems to be some large spiritual ‘entity’ behind the relations with plants and so on. Buhner talks a lot about the use of medicinal plants to help cure people, but he also says:

For it is the meaning, the spirit of the plant, that heals the disease. The plant chemical merely gives it a form in which to travel. And although this form does help our bodies, form to form, we are not (solely) our physical form, and our disease is not (usually) merely a physical form, like a virus… The disease itself is a meaning and cannot be healed merely by supplying a form.

Others say that the plant knowledge is not important and that it is the spiritual energy of the shaman that actuates the healing. This takes a lot of energy, which is stored up like a battery inside the body. Healing can be carried out when the battery is fully charged up, and as the healing is done the battery is used up so that at the end of the healing the shaman feels really exhausted. The ‘battery’ power then has to be recharged before further healing can be done. We have seen above that the heart is an electromagnetic transmitter/receiver and has a strong magnetic field. Energy is required for this to be done and maintained over time. It is also true that some people have more energy in their bodies and hearts than others. We also know that hearts can connect, or ‘entrain,’ with other living entities such as cells, plants, animals, and other hearts. It should come as no great surprise, then, that some people with an abundance of energy in their body and heart could ‘give’ (transmit) some of that energy to a person whose body/heart energy was weak due to illness and so on, and give them an energetic boost that could help them recover their health. However, there is little point in going deeply into this topic, since we only wish here to explore the necessity to achieve a healthy heart-brain balance achievable by the human-nature connection through the perceptive function of the heart.

Nevertheless, individual plants, though they may have their unique spirit, are a part of the interconnected, interacting web of life, the sum of which is a spiritual force that many have experienced as the ‘essence’ of Nature (with a capital ‘N’). The Pgaz K’Nyau perceive two kinds of spirits, k’laz (soul-spirits), which reside in humans and other living creatures such as plants and animals, and k’caj (owner-spirits), which are the spirits that ‘own’ the earth, the land, the water, the sky, and so on, and which are also ‘owners’ of particular areas of forests, for example. They also perceive an overarching natural spirit, a kind of ‘supreme being,’ Taj hti taj dau, who is the owner of nature itself. We could say that Taj hti taj dau is the Pgaz K’Nyau word for ‘God.’

We thus have the notion that Nature, from whom we have all been created, is roughly equivalent to what is called ‘God’ (in monotheistic religions). This large spiritual entity can be perceived directly and experienced, and appears to be the subject of ‘religions.’ Buhner says that the entity “has many names, but only one identity.”

religions are a particular mode of representation

they are not the thing itself

and continues on to say:

This identity is the center from which all things come. And it has always been clear to those who read the text of the world, who are open to the touch of life upon them, that this Mystery is so much greater than Man that it can never be understood by the linear mind.

Since the focus of this paper is Japan, I would like to quote extensively from a friend on Japan’s indigenous spirituality, Shinto.

On Shinto and nature, Shinto was traditionally very deeply rooted in nature, and the folk Shinto groups still are, and engage with nature by taking treks through the mountains, sometimes engaging in great feats of endurance, but that is secondary to being aware of conditions and letting the gods dictate the course and timing. In Shrine Shinto, the officially organized and codified side, the connection has largely been reduced to symbolism, but some of the former connection remains. This is particularly evident in the misogi ritual, which involves cold-water bathing in the ocean, waterfalls, rivers, and so on. Many of the professional priests I talk to, however, have no sense of the spirit world, and consider Shinto to be nothing but a set of traditions. They do see the value in maintaining pre-industrial knowledge and techniques, and choose those in particular for important rituals. A number have told me they wish they could "see" gods the way I and others say we can. I try to point them to times and places where gods are likely to be evident, dawn in particular and any place away from the distractions of modern society. From there, I tell people to be aware of a sense of deep familiarity, like you were coming to a place you loved in your childhood. This sense can be cultivated, but often we shut it out as mere irrationality. If you let it in, though, the insights become more powerful and life becomes more meaningful.

Shinto is also explicit about the perceptive capability of the heart (kokoro). One of the most universally used prayers of purification among Shintoists, Rokkon Shohjoh (Six-Rooted Purity) says, “With your eyes, see all manner of impurity, but in your heart, do not see it.” This is followed by ears, nose, mouth (interestingly, “With your mouth, say all manner of impurity, but in your heart, do not say it”), body (feel) and mind: “In your mind, think all manner of impurities, but in your heart, do not think them.” (Kokoro ni moromoro no fujoh wo omoite, kokoro ni moromoro no fujoh wo omowazu). In Fujikyo and some other sects, the last “kokoro” is pronounced “nakago” to distinguish it. Some sects write it as “inner heart”.

So far within Shinto, the only time it has been suggested to me to try to turn off the internal voice was with people involved in Shugendo, which has strong Buddhist influences. We hiked a rough course up from Kompira to the Ryuo-sha, a Buddhist-Shintoist deity--the Dragon King), and along the way, they told me that if I emptied my mind, I would be able to see the gods and spirits. Every year I continue to hike that trail and practice what they told me. It is a useful technique.

Shinto also recognizes one God, which they see variously as the unification of all that is divine or as the original God from whom all else is derived. Shinto can be considered a loose confederation of nature-based, polytheistic folk religions, held together in an imposed hierarchy, which they have gone along with. For any particular deity, there may be a number of names and descriptions. Amaterasu, the sun goddess, has been erroneously described as Shinto’s principal deity. She is well favored, of course, and worshipped at Shinto’s highest shrine, Ise Jingu, along with Toyouke, the god of agriculture. She is also called Tenshokohdaijin, the on-yomi (Chinese reading of the Chinese characters), with the kun-yomi (Japanese reading) being Amaterasu-Sumeohkami (and I see that in Fujikyo, she is listed as number 14 among the 16 principal deities, just before Jinmu-Jingu and Meiji-Jingu, so therefore principal of Japan’s specific hierarchy as a nation, but past a big list with Myo-o-jin from Buddhism, “Main-Heart God”, “One-Heart God”, Water, Fire and Wind Heart Gods, and so on included).

In Fujikyo, I have heard several names for the Great Divine Spirit: Ohmioya no Kami (Great Illustrious Parent One), and Taisosan-jin (Great Ancestral One, where “Tai” is written as “Ten,” so the meaning of the ‘God-father,’ not as ‘creator’ but as ‘guardian,’ of the heavens is included). Rev. Haruko Shimizu has explained that she considers Fuyoh Miroku-jin (which I will translate loosely as “Embodiment of Mt. Fuji and the Sun,” emphasizing the connection with nature that they seek in such an awe-inspiring locality) to be the Great Spirit, whose name comes up repeatedly in the prayers of that sect, and since he is listed second to Taisosan-jin, they are saying that God Himself has His own ancestors.

I think we can see in Shinto all the elements of the human-nature connection that have been mentioned thus far. The Chinese character for 'heart', when spoken as “kokoro” in Japanese is commonly understood to mean the human “heart” or “mind.” Despite the issue of whether people knew about their physical hearts hundreds of years ago, I do not think there is a great problem in equating kokoro with the human heart. We also see a recognition of an overarching spirit of nature, a “Great Ancestral One” or a “Great Spirit” very similar to the Pgaz K’Nyau Taj hti taj dau.

From the above it is possible to see that ‘God’ as the all-enveloping ‘tablecloth’ of the tonal is merely a shadow representation of ‘God’ in the nagual. It should be clear what religions are supposed to be doing but, in general, are not. The notion of an appropriate heart-brain balance, therefore, is not ‘religion,’ either in the sense of modern, organized religions, or in the sense that it relies fundamentally on subjective belief.

3.3 A sort of conclusion: Where does this path lead?

We have looked at what human happiness might be, and I have concluded that the path to happiness lies through a reconnection to nature through the use of the heart as an organ of perception. What might be the consequences of attempting to put this idea of “happiness” into practice, much as some now insist that the path to “happiness” is to be found through greater wealth and socialized security – through economic growth and social engineering?

Firstly, to go back to where this paper started out, what would this mean in terms of food and energy? Since we would be much more aware of the ‘feelings’ of plants and animals, many of the practices of modern farming would become impossible. We would have to recognize that an intensive use of machinery and chemicals (modern energy-intensive agriculture) in a way that is very ‘impolite’ to plants and other living organisms should be corrected in favour of overtly nonviolent forms of agriculture, such as permaculture and organic farming on small family farms. Greatly reduced use of machinery would mean, 1) more people working on the land, and 2) greater use of farm animals. It is likely that a re-balance of heart-brain cognition on a society-wide basis would trigger the movement of people from big cities to more rural settings. Greater use of animals on farms (the current problem being where to get the animals) would help agriculture as a whole to move back to mixed cropping and livestock-raising farms, rather than the forced separation of cropping and livestock that we have now, and presumably this would also go part of the way to solving the fertilizer problem that will occur when fewer chemicals are used.

So far, there is little news, since I have previously proposed these changes, in the context of diminishing supplies of fossil energy resources, for Japanese agriculture in a presentation in February 2010. In this presentation, I pointed out that since transportation would become problematical then ‘local production for local consumption’ would be a basic principle of this style of agriculture, and thus society as a whole would be likely to shift towards self-sustaining ‘bioregions.’ In this sense, the notion of moving to a society with a better heart-brain balance would appear to be appropriate for a world in which fossil energy use was greatly reduced.

As hinted at above, it should also be pointed out that plants are extremely adept at the use and manufacture of chemical substances, and we would therefore do ourselves a big favour by reducing the chemical pollution of the environment by synthetic chemicals. At the same time, since the heart’s connection with nature depends on electromagnetic radiation and fields, it would also be beneficial to reduce electromagnetic pollution of the environment as much as possible. This is also very much in line with the coming decline in the ability to use fossil energy resources. The future society should be far less polluted than the one we are experiencing now, making a healthy heart-brain balance that much easier to achieve.

Energy production in the bioregions would be local, decentralized forms of energy such as the use of wood, solar or wind power, and the use of animal traction for agriculture. There would be no large-scale industry as we know it now. This would also mean a greatly reduced role for money. This would also be a good match for a society with an improved heart-brain balance. The greater ability of almost all people to use their hearts for perception would make lying, cheating and thievery far less common because people would be much more aware of the intentions of those around them.

The Pgaz K’Nyau have a deep suspicion of any use of money beyond the use of small amounts for petty purchases. Anything more than that creates disparities in wealth between people (which can put the survival of a village in jeopardy) and will ruin lives that are lived simply to amass large amounts of money and property. In the Pgaz K’Nyau view of life and death, the land of the dead (pluz kauj) is a mirror image of the land of the living (le hko). In le hko, rice is delicious and people are important. In pluz kauj, rice is also delicious, but the people there have a love for money and wealth. When the Pgaz K’Nyau travel down from their villages in the mountains to the towns and cities in the valleys, where the people love money and are mostly ‘stuck’ in a linear/verbal/analytic ‘brain’ mode of cognition, they say they are going to pluz kauj, the land of the dead. The inference is that if you do not have a good heart-brain balance and are not capable of perceiving nature with your heart, then you are effectively ‘dead.’

Thus, to sum up briefly, “happiness” is a human condition that can only be reached through a “correct” connection with nature. This connection occurs by using the heart as an organ of perception, as it was meant to be. As a result, we can achieve a more appropriate heart-brain balance. This balance inevitably leads to changes in the moral behaviour of individuals and therefore to changes in society. The combination of these ideas and practices with the kind of, hopefully “happier,” lifestyle we can anticipate when fossil energy resources become scarce helps us to envisage the kind of society that might come into existence in the latter part of the 21st century.

In the midst of the aftermath of the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami disaster, the subsequent nuclear catastrophe at Fukushima No.1 Nuclear Power Station and the financial crisis that currently grips Europe and the United States, I feel strongly that human weakness and stupidity (and a certain amount of deceit) has created huge disasters within societies where for several decades we have heard little else but promises that economic growth was unquestionably leading all mankind toward a secure and comfortable lifestyle. I think it is now time to wake up to what is truly wrong with society and begin to educate everyone, especially children, on how to regain their birthright (the ability to use the heart as an organ of perception) and an appropriate heart-brain balance, and move toward the society of the 22nd century, where true human happiness may be achievable. While it may seem that this is only one possible future, I believe eventually this is the future toward which all human societies will eventually converge, whether in the 22nd or 23rd centuries, or later.

Illustration adapted from one here.

This is an excerpt from an article originally published on April 24, 2010 as "S 510 is hissing in the grass by Steve Green.

In "Hissing in the Grass," Steve Green writes that

S 510, the Food Safety Modernization Act of 2010, may be the most dangerous bill in the history of the US. It is to our food what the bailout was to our economy, only we can live without money.

“If accepted [S 510] would preclude the public’s right to grow, own, trade, transport, share, feed and eat each and every food that nature makes. It will become the most offensive authority against the cultivation, trade and consumption of food and agricultural products of one’s choice. It will be unconstitutional and contrary to natural law or, if you like, the will of God.” ~Dr. Shiv Chopra, Canada Health whistleblower

It is similar to what India faced with imposition of the salt tax during British rule, only S 510 extends control over all food in the US, violating the fundamental human right to food.

Monsanto says it has no interest in the bill and would not benefit from it, but Monsanto’s Michael Taylor who gave us rBGH and unregulated genetically modified (GM) organisms, appears to have designed it and is waiting as an appointed Food Czar to the FDA (a position unapproved by Congress) to administer the agency it would create — without judicial review — if it passes. S 510 would give Monsanto unlimited power over all US seed, food supplements, food and farming.

In the 1990s, Bill Clinton introduced HACCP (Hazardous Analysis Critical Control Points) purportedly to deal with contamination in the meat industry. Clinton’s HACCP delighted the offending corporate (World Trade Organization “WTO”) meat packers since it allowed them to inspect themselves, eliminated thousands of local food processors (with no history of contamination), and centralized meat into their control. Monsanto promoted HACCP.