"Home ownership is a means to an end. It is not necessary for all people in all places. What all people want is housing affordability, security, and autonomy. A place they know they can come to, where they are in control of their own lives, which can be arranged to best serve their interests, tastes and lifestyle, and which will not enslave them financially. It is these values which have been so steadily undermined in Australia over the past decade in particular.

"Home ownership is a means to an end. It is not necessary for all people in all places. What all people want is housing affordability, security, and autonomy. A place they know they can come to, where they are in control of their own lives, which can be arranged to best serve their interests, tastes and lifestyle, and which will not enslave them financially. It is these values which have been so steadily undermined in Australia over the past decade in particular.

In some European countries like Germany, only about half of all households own their home. Many people have cited them, in an effort to wean Australians off their preference for ownership. However, the situation here is very different to that in Germany. There, tenants have substantial rights protecting their tenure and enabling them to decorate and to a certain extent modify their abode. Most importantly, the housing market is not inflating, so there is no expectation that rents will outstrip inflation into the future." (Dr Jane O'Sullivan) [1]

Submission to the Home Ownership Inquiry

House of Representatives Economics Committee

By Dr Jane O’Sullivan, June 2015

I am grateful to the Committee for its consideration of Home Ownership, which is an issue of increasing concern for Australians.

Home ownership is a means to an end. It is not necessary for all people in all places. What all people want is housing affordability, security, and autonomy. A place they know they can come to, where they are in control of their own lives, which can be arranged to best serve their interests, tastes and lifestyle, and which will not enslave them financially. It is these values which have been so steadily undermined in Australia over the past decade in particular.

In some European countries like Germany, only about half of all households own their home. Many people have cited them, in an effort to wean Australians off their preference for ownership. However, the situation here is very different to that in Germany. There, tenants have substantial rights protecting their tenure and enabling them to decorate and to a certain extent modify their abode. Most importantly, the housing market is not inflating, so there is no expectation that rents will outstrip inflation into the future. [1] This Submission was made in the name of Dr Jane O'Sullivan.

In Australia, renters are faced with ever-tightening budgets as rents are ratcheted up, and the prospect of termination of lease forcing them to move, with great uncertainty about where they might be able to afford to move to. They generally have little if any control over the fittings and finishes in their home, the energy mix and efficiency, or the level of security afforded. The only insurance against ever-increasing insecurity is home ownership.

I hope that this inquiry will consider policy options both to improve the accessibility of home ownership, and to improve the security and rights of tenants.

Current rates of home ownership

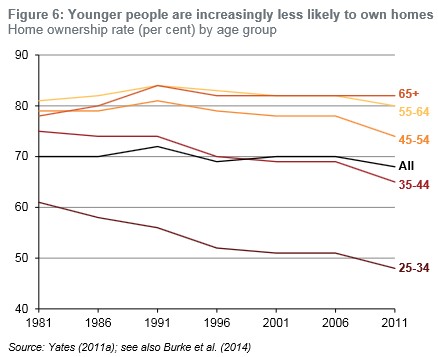

Home ownership is still relatively high in Australia, but most current households bought their first home before the escalation in property values, that began in the late 1990s. The rate of decline in home ownership among younger cohorts between the 2006 and 2011 census is disturbing. The following chart is reproduced from Leith van Onselen [2]

Behind this relatively small change in overall home ownership is a vast increase in household debt levels. The ratio of mortgage debt-to-disposable income exceeded 140% in December 2014. [3] This is up from an average debt of 27 per cent of average income in 1985.[4] The Economist reported that, since the 1970s, virtually the entire increase in the ratio of private-sector debt to GDP around the world has been caused by rising levels of mortgage lending.[5]

LF Economics documents that housing in Sydney and Melbourne requires more years of median income to pay down the capital value than in any other city except Vancouver.[6] Vancouver is another city beset by very high rates of immigration-fuelled population growth. When one factors in that mortgage interest rates are higher in Australia than elsewhere, even at our current relatively low rates, affordability in Australia is extremely low on world standards. If setting aside 30% of a median income for the purpose, Sydney or Melbourne households would spend 6 years saving for a 20% deposit, and 23 years paying down the principle on a loan for 80% of median home price, plus a further 20 or more years to cover the interest, according to the LF Economics report. Spending 30% or more of disposable income on housing is considered to indicate housing stress. Thus the median household entering the market faces official housing stress for their entire working life. Let us remember that households entering the market as first-home-buyers initially average incomes well below median.

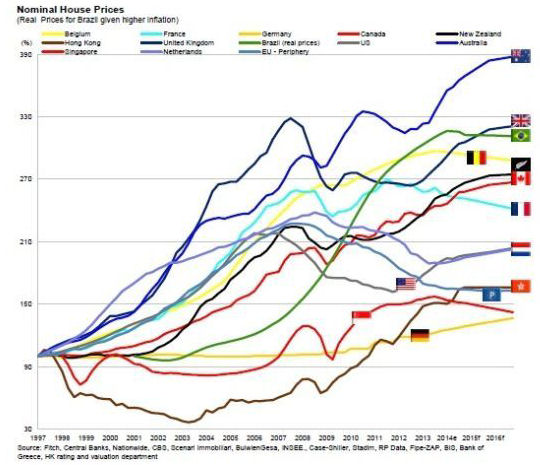

The ratings agency Filch found Australia had the highest growth in dwelling prices since 1997. This is unsurprising, since we had the highest population growth also.

Source [of Nominal House Prices diagram]: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-01-15/fitch-graph-of-housing-price-growth-since-1997/6018762

Thus Australians have shown very low elasticity of demand for housing, absorbing huge cost increases with relatively little change in purchasing behaviour – accommodated by a massive change in debt, impacting on consumption behaviour and work-life balance. A declining proportion of income spent on every-day consumption means a smaller multiplier-effect of each person’s productivity in the whole economy: fewer jobs are needed to service this consumption, while more people try to increase their hours of work to pay their mortgage. Workforce participation can only fall as the least competitive in the labour market are forced out.

There are two main reasons for this low elasticity:

a) Conditions in the rental market have worsened also, making long-term renting ever less attractive. Median rent statistics hide the fact that new additions to the rental stock offer less and less amenity. Like-for-like, rents have risen faster.

b) Expected further inflation of housing makes those without property nervous that they will be permanently locked out if they do not buy in as soon as possible.

It is often argued in the media that rising house prices have been driven by Australians demanding bigger and fancier houses. This is patently untrue. If it were true, the standard post-war three-bedroom bungalow in inner ring suburbs would be decreasing in value. The average ‘house’ may have increased in size, but not the average abode, when apartments are included. It is land which is inflating, not the cost of construction nor the scale of homes.[7]

The truth is that the average standard of accommodation in Australia has been steadily declining, with the average young couple settling for a smaller apartment, in a noiser and less green neighbourhood, with less contact with neighbours, and/or a greater distance from work and community amenities. Most will have spent more of their adult life either in their parental home or in share-houses, than their parents’ generation. Most will spend a far greater proportion of their life-time earnings just keeping a roof over their head. All these factors contribute to considerable loss of quality of life in Australia.

An increasing number of reports document the social stresses of housing unaffordability. The Age reported on multiple families living together because they can't afford the rent.[8] Minimum wage workers are being pushed to the fringes of Sydney, with UWS urban studies researcher Dallas Rogers affirming that geographical separation of rich and poor creates a cycle of disadvantage.[9]

The inflation of house prices does not benefit home owners, as the inflation will equally affect the home they buy to replace one sold. This was well explained in a recent letter in the Canberra Times:

“If you bought a house in 1995 for $200,000 and sold it in 2007 for $600,000, how much profit did you make?

“A) Nil. B) About $200,000. C) $400,000. D) None of the above. The correct answer for most people would be D. If it was your only house, you would have needed to buy another house in 2007 to replace the one you sold. An equivalent replacement would cost $600,000. Add to that the costs of selling (say $20,000) and the costs of buying and moving (around $40,000), then you would have spent an extra $60,000 to be in the same position you were in 1995.

“Many people think that they are better off when the price of their house goes up. They aren't. It is still the same asset. What does go up is their capacity to borrow.

One of the most outstanding achievements of the last Liberal/National government was to double household debt. The profit of Australia's major banks was closely aligned with this increase in debt.”[10]

The Reserve Bank of Australia suggested that consumption growth in Australia will depend on further housing inflation, with the ‘wealth effect’ (the illusion of greater wealth) encouraging households to spend.[11] Thus they are relying on households exercising their greater capacity to borrow, using debt to pump up GDP. Given the effect of housing unaffordability on the ability of households to save for retirement, others stress importance of housing equity to fund retirement, advocating the use of reverse mortgages. Yet, if households are coerced into spending their growing home equity instead of paying down their mortgage, they will not have equity to draw on in retirement. This attitude appears to be merely kicking the can down the road – to land in a very rocky place, when the current young and over-leveraged cohort reach retirement. Private debt cannot sustainably grow GDP any more than fiscal debt, and it’s about time our macroeconomists admitted it.

In an article in The Conversation, Keith Jacobs argues that the majority of people would benefit from falling real estate prices, but the media and political discourse spruiks housing inflation as enrichment:

“Why has this crisis of affordability not been addressed by government? A major reason is that powerful industry groupings such as the financial sectors, property developers and real estate lobby groups have been spectacularly successful in maintaining pressure on the policymakers to privilege wealthy homeowners at the expense of less well-off households.”[12]

Demand and supply drivers in the housing market

The main factor driving these stressors is population growth.[13] Population did not initiate the past 15 years’ hyper-inflation – that was primarily the capital gains tax discount. But population growth was used since the mid-2000s to prop up the bubble caused by that rash and inequitable gift to the rich.

Was it the faltering of housing inflation in 2011 that caused the Gillard government to backflip on its election promise of reducing immigration, and further escalate population growth despite worsening unemployment?

In countries with stable populations, like Germany, property values are near stable, and housing is not a magnet for speculative investment. It is free instead to serve its occupants. Japan’s property bubble ended as its population growth tailed off. Australia’s population growth remains far higher than almost all other OECD countries. This is not only at the expense of affordable housing, but of fiscal balance, with the increased infrastructure costs amounting to over $100,000 per person added[14] , and already accounting for State government debts.[15]

Yet, because it forces up aggregate levels of debt, population growth is great for the banks. Unfortunately, policy-makers tend to turn to banks for macroeconomic advice, apparently oblivious to the conflict of interest between the banks and the populace they leverage. CommSec’s quarterly State of the States reports, which Premiers spruik as a measure of their personal success, invariably places population growth as a dominant determinant of economic performance. Yet the same reports show incomes more consistently outstripping cost-of-living in the states with least population growth. Only by ignoring per capita metrics are the faster-growing states portrayed as more successful. If headline economic indicators were routinely reported per capita, and change in public and private debt were subtracted from them, we would have a much more realistic view of wealth trends. This is the story the banks do not want to tell.

It is frequently claimed that house price rises are due to inadequate supply of housing. This excuse is wearing thin with the public, who see that government policy has taken every opportunity to increase demand. In addition to the expanded immigration program has been added increasing access of foreign investors to Australian real estate. The capital gains tax discount remains sacred, even as welfare and community services are sacrificed as ‘fiscally irresponsible’. Intermittently, first-home-buyer grants further fuel demand and ratchet up prices.

Foreign investment in real estate does not increase supply, it merely fuels the demand, and further displaces prospective home-owners. Without foreign capital inflows, the supply of housing outstripped demand growth continuously from 1950 to 2007.[16] There is an acknowledged tendency for foreign owners, particularly Chinese, to leave properties empty,[17] with the effect that their purchase decreases, rather than increases, housing supply. If developers claim that they can no longer find up-front funding for new ventures on-shore, it is only because, at the current value of land, their proposed development is not commercially viable. A liberal government should not be interfering in the market-place to prop up such unviable ventures.

By introducing investors who have much lower costs of capital than Australians, as well as providing a haven for those who may be laundering corrupt earnings,[18] the prices can be ratcheted even further beyond what is economically rational for Australians. This can only progressively lock Australians out of home ownership, and leave them increasingly beholden to foreign landlords.

Such fuelling of demand plays into the hands of those with control over supply. A recent University of Queensland study[19] found that speculation in peri-urban land was highly lucrative for those with political connections, who have more than a knack for picking the next area to be rezoned. Likewise, approvals for height relaxations on inner urban developments are equally lucrative. It serves developers to present supply as the problem for housing affordability, and themselves as the heroic saviours. Their claims that foreign investors are needed to get projects up are purely self-serving. Their investment in numerous lobbyists and think tanks spruiking population growth ensures that supply is never met, and ever more concessions from government can be requested to help them ease the pressure that they themselves have bought and paid for.

The proportion of investment housing relative to owner-occupied housing

The main impact of the capital gains tax discount was to attract investors into the property market, massively intensifying demand. It goes without saying that housing investment decreases home ownership. Investors need tenants, and those households competed out of home ownership by cashed-up investors are forced to remain tenants. Population growth ensures rental vacancy rates are kept very low, forcing up rents and motivating renters to stretch their credit limit to purchase property. Once heavily mortgaged, both home owners and investors depend on further price increases to recover their investment. But this can only happen at the expense of younger people entering the housing market, each cohort facing higher indebtedness than the last. Each year housing inflation continues, more investors are attracted, further decreasing the proportion of housing that is owner-occupied. It is a vicious cycle.

The Prime Minister was clearly declaring himself on the side of investors against home-owners, when he recently said “I do hope that our housing prices are increasing.” Anyone who thinks that property owners can continue enjoying investment growth well above CPI, without housing affordability deteriorating inexorably, is deluding themselves. Yet, as the old adage goes,

“It's hard to get someone to understand something when their salary depends on them not understanding it.”

The impact of current tax policy at all levels

Tax policy currently preferences investors over home owners, particularly through the following elements:

• Capital Gains Tax discounting;

• Tax deductibility of interest rates;

• Depreciation of buildings;

• Negative gearing.

Together, these measures mean that financing an investment property is much cheaper than financing a home. This is inequitable. Changes should aim to level the playing field, removing systemic advantages of investors over owner-occupiers.

No interest payments on real estate should be tax deductible. These are not productive investments, they merely serve to flood demand and inflate housing prices. Those with money to invest should be free to invest in property, but those who have to borrow to do so should not get special treatment from government, as if they are doing the economy a favour, because they are not.

The ability to depreciate buildings, rather than merely deduct the costs incurred in maintaining them, is also an inequitable means for investors to minimise their costs. In a rising market, where the building has probably increased in value in spite of wear and tear, this is a dishonest device which further disadvantages owner-occupiers.

The capital gains tax discount is a gift from the tax-payers to the richest members of society. Saul Eslake documented the extent to which the introduction of this discount in 1999 stimulated an enormous increase in the use of the negative gearing facility to shift taxable income to lightly-taxed capital gain.[20] Borrowing for property investment and the proportion of loss-making landlords increased dramatically.

Before the capital gains discount, negative gearing was mostly only a means of deferring tax from current income to future capital gain. However, the ability to deduct interest and depreciation contributed to the amount of income offset. It is the capital gains discount that has turned negative gearing into a major tax rort. Saul Eslake (op. cit.) estimated the tax avoided to be in the order of $5 billion in 2011. He concluded, “This is a pretty large subsidy from people who are working and saving to people who are borrowing and speculating.”

The claim that abolition of negative gearing would force rents up has been debunked by a number of commentators, who have demonstrated that its abolition between 1985 and 1987 did not result in any consistent rent response across Australian cities – in Sydney and Perth, where vacancy rates were unusually low, rents rose, but in other cities they were unchanged or fell.[21]

Other measures have been implemented to advantage first-home buyers in the marketplace. These include first-home buyers’ grants and stamp duty waivers. These measures invariably serve merely to push the price of real estate further upward. Prices are limited by buyers’ capacity to pay, and if this is supplemented by government, the first-home buyers simply pay more. The impact on prices affects all buyers, and has the impact of increasing total mortgage debt carried by the community.

What is needed is to remove the advantages enjoyed by speculative investors, not to fuel an arms war between investors and home buyers.

Opportunities for reform

It is not difficult to identify a range of measures which would stem housing inflation and shift speculative investors to more productive investments. What is lacking is the political will.

The following measures are roughly in order of impact, from the greatest and most certain to the least or less probable.

1. Drop immigration quotas significantly and tighten conditions on most forms of temporary work immigration, allowing population growth to taper off.

2. Remove the capital gains tax discount (across all forms of investment income), allowing only a CPI adjustment. Capital gains tax should not apply to the family home, or at least should be net of all expenses in buying the next home.

3. Disallow foreign investment in property. This is purely inflationary, and allows foreigners privileges in Australia which are not reciprocated.

4. Disallow mortgage interest payments and building depreciation as tax deductions.

5. End negative gearing, allowing tax deductions to be claimed only against the income from the activity that incurs them (but permitting costs to be carried forward against future rents or capital gains).

Land tax has been proposed as an additional measure, but is problematic in an inflating housing market. It means that people can no longer even count on home ownership to insulate them from rising costs of housing. As their home rises in market value, through no fault of their own and conferring no advantage on them, they nevertheless face rising tax. Rates are already a land tax that many long-term residents find hard to endure. A land tax can only force more of them out and accelerate the geographical separation of rich and poor.

However, tax on vacant property may be worthwhile, to deter speculative behaviour and prevent investors withholding stock from the market. Any property vacant for more than three months, without being under contract or development application, may be subject to the tax.

The nation’s elected representatives need to decide whether they support:

- on the one hand, ongoing profiteering by developers and real estate speculators, who are increasingly not even Australian, knowing that this can only mean increasing levels of household debt, housing stress, homelessness, inequality of wealth and geographic separation of rich and poor generating slums, crime and civil unrest,

- or on the other, stabilisation of land values and the diversion of speculative investment to productive uses in enterprise and infrastructure, knowing that this means an overall drop in investment returns (including their own) compared with recent expectations, but may avert a bigger drop that an over-inflated bubble must ultimately cause.

To use Tony Abbott’s parlance, “Whose side are you on?”

A rational and sincere public servant should know that the current situation is unsustainable and highly damaging to the fabric of society. Unfortunately I have seen little evidence of such a combination of wisdom and sincerity.

“Surely by now there can be few here who still believe the purpose of government is to protect us from the destructive activities of corporations. At last most of us must understand that the opposite is true: that the primary purpose of government is to protect those who run the economy from the outrage of injured citizens.”

Derrick Jensen – “Endgame: The Problem with Civilization”

Jane O’Sullivan

June 2015

FOOTNOTES

[1] Forbes 02/02/2014. In World's Best-Run Economy, House Prices Keep Falling -- Because That's What House Prices Are Supposed To Do. http://www.forbes.com/sites/eamonnfingleton/2014/02/02/in-worlds-best-run-economy-home-prices-just-keep-falling-because-thats-what-home-prices-are-supposed-to-do/

[2] van Onselen, L. 2015 Winners and losers in negative gearing reform. Macrobusiness 31/05/2015. http://www.macrobusiness.com.au/2015/03/will-hurt-negative-gearing-reform/

[3] Leith van Onselen 2015. Australian household debt ratios hit record. Macrobusiness 31/05/2015 http://www.macrobusiness.com.au/2015/03/australian-household-debt-ratios-hit-record/

[4] Kenneth Davidson 2015. Left out in the cold by a state reluctant to invest. The Age, 25/01/2015.

[5] The Economist 31/01/2015. Safe as Houses. http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21641206-banks-have-been-boosting-mortgage-lending-decades-expense-corporate

[6] LF Economics 2015. Housing affordability in Australia. https://gumroad.com/l/UXjubSee summary at http://www.macrobusiness.com.au/2015/04/oz-housing-affordability-measured/

[7] Van Onselen 2015. Australia’s idiotic land bubble. Macrobusiness 10/04/2015. http://www.macrobusiness.com.au/2015/04/australias-idiotic-land-bubble/

[8] The Age, 20/01/2015. Multiple families living together because they can't afford the rent.

[9] Inga Ting 2015. The Sydney suburbs where minimum wage workers can afford to rent, SMH, 9/6/2015 http://www.smh.com.au/nsw/the-sydney-suburbs-where-minimum-wage-workers-can-afford-to-rent-20150608-ghjc6v.html

[10] Keith Calvert, Phantom Profit, The Canberra Times 4/6/2015.

[11] Michael Pascoe 2015. RBA remains dovish, but that's no surprise. Sydney Morning Herald 8/05/2015. http://www.smh.com.au/business/the-economy/rba-remains-dovish-but-thats-no-surprise-20150508-ggx4s9.html

[12] Jacobs K. 2011. Why falling house prices aren’t the calamity the media would have you believe. The Conversation, 13/12/2011. http://theconversation.edu.au/why-falling-house-prices-arent-the-calamity-the-media-would-have-you-believe-4547

[13] Ridiculous immigration fires housing spike – Bob Carr. The Australian http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/immigration/ridiculous-immigration-fires-housing-spike-bob-carr/story-fn9hm1gu-1227393713757

[14] O’Sullivan J. 2014. Submission to the Productivity Commission Inquiry into Infrastructure provision and funding in Australia. http://www.pc.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/135517/subdr156-infrastructure.pdf

[15] Daly, J. 2014. Budget pressures on Australian governments 2014. Grattan Institute. http://grattan.edu.au/report/budget-pressures-on-australian-governments-2014/

[16] Soos P. 2011. Debunking the myths peddled by Australia’s property bubble ‘deniers’. The Conversation 14/12/2011. https://theconversation.com/debunking-the-myths-peddled-by-australias-property-bubble-deniers-4488

[17] Callick, R. 2015. Why the Chinese are willing to pay over the odds for local property. The Australian, 11/06/2015. http://m.theaustralian.com.au/business/opinion/why-the-chinese-are-willing-to-pay-over-the-odds-for-local-property/story-e6frg9fo-1227392052366

[18] Nick McKenzie, Richard Baker, John Garnaut 2015.Corrupt overseas buyers ramp up property price, burn locals. The Age, 23/06/2015. http://www.theage.com.au/national/corrupt-overseas-buyers-ramp-up-property-price-burn-locals-20150622-ghu5pn.html

[19] Murray C. and Frijters P. 2015. Clean Money in a Dirty System: Relationship Networks and Land Rezoning in Queensland. IZA Discussion Paper No. 9028, April 2015. http://ftp.iza.org/dp9028.pdf

[20] Saul Eslake 2013. Fifty years of housing failure. Address to the 122nd Annual Henry George Commemorative Dinner The Royal Society of Victoria, Melbourne 2nd, September 2013. https://www.prosper.org.au/2013/09/03/saul-eslake-50-years-of-housing-failure/

[21] Greg Jericho 2015. Negative gearing: a legal tax rort for rich investors that reduces housing affordability. The Guardian 19/03/2015. http://www.theguardian.com/business/grogonomics/2015/mar/19/negative-gearing-a-legal-tax-rort-for-rich-investors-that-reduces-housing-affordability

Comments

quark

Tue, 2015-08-11 13:20

Permalink

Symptoms of housing stress in the "comfortable" suburbs?

Dennis K

Tue, 2015-08-11 20:54

Permalink

Housing an indicator of a lousy economy

Add comment