Although Church of England clergy arrived with the first fleet and were appointed to manage social policy in Australia, including ongoing settlement via immigration, the Church of England seemed to concentrate less on independently building its own congregations and institutions than the Catholic Church.

Although Church of England clergy arrived with the first fleet and were appointed to manage social policy in Australia, including ongoing settlement via immigration, the Church of England seemed to concentrate less on independently building its own congregations and institutions than the Catholic Church.

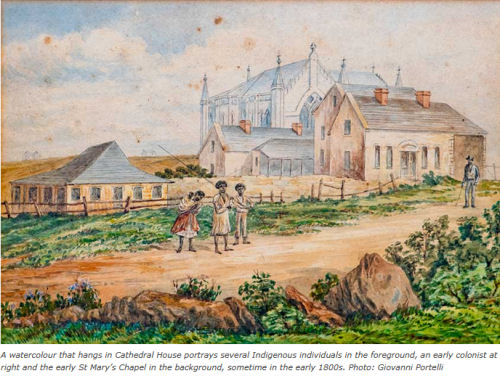

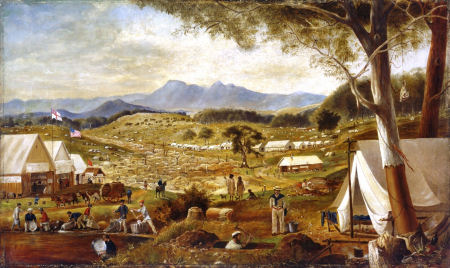

The Catholic Church actively encouraged Catholic immigration to Australia especially from the 1850s, the time of the first Australian goldrush. This was partly in response to the influx of Irish immigrants fleeing famine and political  persecution, who formed a largely captive population, ideologically, and partly in response to the gold rush. The Catholic Church, like other institutions, invested in gold mining operations and land speculation activities in those areas, relying on the massive population influx. The wealth generated from gold mining also contributed to the funding and land for Catholic missions, schools, hospitals and other social services. Catholic 'expertise' in running 'managed reserves' and 'missions' - gated compounds - for displaced First Nations people was in demand around the gold-fields, where mining rapidly razed the forests they lived and hunted in, and shelter for anyone was in extremely short supply. We can see this from the busy devastation illustrated in colonial paintings by Eugene von Guerard and others, or the watercolor of aboriginal women near St Mary's chapel, somewhere in NSW. (See https://catholicweekly.com.au/life-as-a-catholic-in-an-1821-colony/).

persecution, who formed a largely captive population, ideologically, and partly in response to the gold rush. The Catholic Church, like other institutions, invested in gold mining operations and land speculation activities in those areas, relying on the massive population influx. The wealth generated from gold mining also contributed to the funding and land for Catholic missions, schools, hospitals and other social services. Catholic 'expertise' in running 'managed reserves' and 'missions' - gated compounds - for displaced First Nations people was in demand around the gold-fields, where mining rapidly razed the forests they lived and hunted in, and shelter for anyone was in extremely short supply. We can see this from the busy devastation illustrated in colonial paintings by Eugene von Guerard and others, or the watercolor of aboriginal women near St Mary's chapel, somewhere in NSW. (See https://catholicweekly.com.au/life-as-a-catholic-in-an-1821-colony/).

In the course of providing a supportive community for Catholic immigrants, the Church built up its base and influence. It has a long history of running migration programs for different countries (Spain, Portugal) and pre-Revolutionary France, where it was the de facto government and responsible for the main immigration program and for building and running educational, health, and welfare institutions in French Canada until the 1980s.[1]

As the Catholic population grew, so too did the influence and wealth of the Church.

This is particularly notable in Catholic education to this day, in the form of independent catholic schools (and universities), which are the cheapest private alternative to Australia's  state schools. By the late 19th century, the Catholic Church had successfully established its network of independent Catholic schools. This was unique at the time, as other denominations struggled and failed to gain similar autonomy and influence. In the late 19th century, Australian state schools became non-denominational and secular, with Victoria in 1872 the first to established a free, secular, and compulsory education. From the 1960s and 1970s, Catholic schools have been assisted with state subsidies, however this is provided per student for all Australian students, wherever they go to school. Save our Schools, however, states that the funding allocated per student to Catholic and other independent schools is now greater than the allocation per student in state schools. By 2024, public schools were funded at 87.6% of their Schooling Resource Standard (SRS), while Catholic schools were funded at 104.9% of their SRS, indicating that Catholic schools receive more relative funding compared to public schools. So, while state funding per student for Catholic schools may not be greater in absolute terms compared to public schools, the overall funding landscape, including federal contributions and additional revenue sources, results in a higher total income per student for Catholic schools. This disparity highlights the systemic issues in funding distribution that favor private institutions over public ones.

state schools. By the late 19th century, the Catholic Church had successfully established its network of independent Catholic schools. This was unique at the time, as other denominations struggled and failed to gain similar autonomy and influence. In the late 19th century, Australian state schools became non-denominational and secular, with Victoria in 1872 the first to established a free, secular, and compulsory education. From the 1960s and 1970s, Catholic schools have been assisted with state subsidies, however this is provided per student for all Australian students, wherever they go to school. Save our Schools, however, states that the funding allocated per student to Catholic and other independent schools is now greater than the allocation per student in state schools. By 2024, public schools were funded at 87.6% of their Schooling Resource Standard (SRS), while Catholic schools were funded at 104.9% of their SRS, indicating that Catholic schools receive more relative funding compared to public schools. So, while state funding per student for Catholic schools may not be greater in absolute terms compared to public schools, the overall funding landscape, including federal contributions and additional revenue sources, results in a higher total income per student for Catholic schools. This disparity highlights the systemic issues in funding distribution that favor private institutions over public ones.

The efforts of the Catholic Church in the 19th and early 20th centuries laid the groundwork for a robust political influence system in Australia, which continues today. It is based on ideological education and institutional networks established from childhood, plus the ability to influence opinion and values through wealth, manpower, and representatives, via its own and wider media. People retain values inculcated in childhood and reinforced by their social milieu. The Church's ability to mobilize resources and establish institutions significantly influenced the social and political fabric of the country. In 1955, during "the Split," with the help of Bob Santamaria's Catholic Social Studies Movement, the Vatican managed to weaken the Australian Communist Party and sent the Labor Party into the wilderness for years through opening the party to the DLP.

Historical Influence of the Catholic Church on First Nations Populations

From the early days of settlement, Catholic missionaries established missions aimed at converting First Nations people to Christianity. These missions often focused on education, religious instruction, and social services, leveraging the Church’s human and financial resources to reach remote areas.

The cultural impact was, of course, formidable, along with other settlement forces. While some missionaries aimed to protect First Nations cultures—such as the Ernabella Mission (S.A.), Kowanyama Mission (Qld), Oodnadatta Mission (S.A.), Palm Island Mission (Qld), and Halls Creek Mission (W.A.)—most sought to assimilate First Nations people into European ways of life, discouraging traditional practices and languages, leading to huge cultural disruption. The missions resembled orphanages, where children were removed from their families and tribes, receiving limited European-style education, often sent to farms as servants or laborers, often never paid.

Political Influence of the Catholic Church on First Nations Attitudes Towards Immigration

You might logically expect First Nations people to actively resent and resist Australia's continuous increases in immigration, especially with the acknowledgment of Terra Nullius. (I must admit that this did not occur to me until some local Koories at Winja Ulupna Women's house, where I was working in the mid-1980s, loudly gave me their opinion on immigration and multiculturalism.)

So why do we hear very few resistive First Nations voices?

Did the Catholic education and mission system affect First Nations attitudes towards immigration? Did the hand-me-down European cultural left-overs somehow make First Nations people forget about the cruelty of being dispossessed of their land and ancestral social systems from the first settlement?

The Catholic Church has historically made social issues its political and ideological territory, including the rights of Indigenous peoples. It has a de facto open-borders attitude towards immigration, couched in humanitarian values, but its enormous land acquisitions mean this is also good business.

Through its various programs and initiatives, including schools and missions, the Church engages with both First Nations and non-First Nations populations in Australia, authoritatively leading discussions on social issues, many of which, like housing affordability and homelessness, are strongly affected by mass immigration and disproportionately impact people of First Nations descent. The Catholic Church tries to get First Nations people to view immigrants through a lens of shared struggle and resilience. But only 14,000 are refugees among Australia's now over half a million, and growing, annual intake of immigrants. The overwhelming majority have homes in the places they are coming from, and they represent a significant portion of competition for access to housing, contributing to around 80% of Australia’s total population growth per annum. Nor are most new migrants victims of ethnicism or racism, for most also come from homes amongst people of similar appearance and beliefs. It seems callous and dishonest to conflate immigration in general with past and ongoing First Nations dispossession.

Where mass immigration negatively affects an issue it wants to promote, the Church, like the YIMBY property developers, is silent, or emphasises aspects like racism (the 'other') or generosity over local rights and material basics. This stance is antithetical to self-determination, which lies at the centre of the Australian struggle, for both First Nations and non-First Nations people.

Mainstream media which, like the Catholic Church, is in the land-speculation business, is not going to invite anyone, let-alone First Nations people, to speak up against mass immigration, no matter how reasoned their arguments. Prominent figures, including First Nations ones, have publicly supported mass immigration, apparently echoing Church justifications. This creates the idea that there is broad acceptance of immigration within the First Nations population. But, while some First Nations people may adopt favorable views towards mass immigration, a significant number are indignant about the obvious ecological, social, and political impacts of continuous and increasing immigration, for reasons which should be bloody obvious.

I should qualify this article by acknowledging the good that individuals working in churches of various kinds do in providing identity and assembly places for people in Australia who need this. But one cannot help but be critical of the way those institutions themselves generally comfort government policy and elite economic policies over real self-determination. One might contrast the more representative role of churches in Eastern and middle Europe where they actively cooperate in political struggles, such as in Armenia and Ukraine. One might also distinguish the difference between religious beliefs and religious institutions.

NOTES

[1] See "Chapter Twenty: No Revolution in Quebec or Ireland: Church, monarchy and high fertility persist," in Sheila Newman, Land Tenure and the Revolution in Democracy and Birth Control in France, Countershock Press, 2024.

[2] "The Australian Government (the Commonwealth) provides recurrent funding for every student enrolled at a school. In 2025, recurrent funding for schools is estimated to total $31.1 billion. This includes $11.9 billion to government schools, $10.4 billion to Catholic schools and $8.7 billion to independent schools.24 Mar 2025."

By 2024, public schools were funded at 87.6% of their Schooling Resource Standard (SRS), while Catholic schools were funded at 104.9% of their SRS, indicating that Catholic schools receive more relative funding compared to public schools. So, while state funding per student for Catholic schools may not be greater in absolute terms compared to public schools, the overall funding landscape, including federal contributions and additional revenue sources, results in a higher total income per student for Catholic schools.

Add comment