It is surprising to pick up a book about wealth statistics and find that it segues so readily into another about psychopathology in young girls. The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone takes a revealing look at how wealth is distributed within different developed countries and Reviving Ophelia illustrates the decline of women's rights in the face of aggressive pornography and its effect on girls. Children and the general public were not widely exposed to explicit pornography and sexual sadism in the ‘traditional’ mass media of the industrial age, although these notions were commonly implicit in images and concepts used for marketing all kinds of things. Between that time and now, in 2011, the depiction of women almost exclusively as victims and objects of violence and pornography, explicitly and for that sole reason, has become a global business which operates 24/7. The implicit violence and sexualisation of women in ordinary marketing has also continued. At the same time, the official message is that western women don’t need Feminism anymore because equality has prevailed.

It is surprising to pick up a book about wealth statistics and find that it segues so readily into another about psychopathology in young girls. The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone takes a revealing look at how wealth is distributed within different developed countries and Reviving Ophelia illustrates the decline of women's rights in the face of aggressive pornography and its effect on girls. Children and the general public were not widely exposed to explicit pornography and sexual sadism in the ‘traditional’ mass media of the industrial age, although these notions were commonly implicit in images and concepts used for marketing all kinds of things. Between that time and now, in 2011, the depiction of women almost exclusively as victims and objects of violence and pornography, explicitly and for that sole reason, has become a global business which operates 24/7. The implicit violence and sexualisation of women in ordinary marketing has also continued. At the same time, the official message is that western women don’t need Feminism anymore because equality has prevailed.

Some people are more equal than others, especially if they are not women

In the Australian Financial Review, September 13, 2011, Deidre Macken writes, “After a week when economic statistics made a lie of our feelings of being worse off, it seems like an opportunistic time to check how good we are at reading ourselves. Obviously we are not good judges at assessing our economic well-being. Repeat after me – we are a lucky people, living in a country that’s never been luckier.”[1]

Without going into the adequacy of the indicators she used but does not reference, was Deidre talking about averaged statistics or was she talking about the way they are distributed throughout the nation?

I chose a quote from a female financial journalist to introduce the feminist implications of the theories of two books. One was published nearly two decades ago and the other was published last year. The earlier one is by Mary Pipher, with the title of Reviving Ophelia: Saving the selves of adolescent girls. It was published by Riverhead Books, New York, 1994. The second book is by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett. It’s title is The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone, and it was published by Penguin in 2010.

Both books are about the impacts of inequality as you and I experience it, rather than the global economics of inequality between different countries by which the first and the third world are often defined. I found these books interesting particularly in the light of the recent inquiry into human rights in Australia, which ignored Australian citizens’ rights by concentrating on international rights. Citizens’ rights require active democracy and laws to facilitate this, whereas global human rights are relative abstractions, requiring recognition by national governments in hard-to-enforce treaties.

The Spirit Level: Why Equality is better for everyone

Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett in The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone, Penguin 2010 beg the question of defining countries as rich or poor according to their average wealth. The book points out that, although Australia or the United States might have relatively large GDPs for their total populations, large sections of those societies are politically, materially, socially and physically disempowered and disadvantaged by their relative poverty. The authors imply that these differences drive seriously negative outcomes in almost any area you care to think of. The more unequal you are with the people geographically close to you – in your neighbourhood, your state, your nation - the more anxious and dysfunctional you are likely to be. Inequality is actually an indicator of relative unhappiness and that unhappiness is linked to many social and physical ills, including violence and obesity.

Further on we will relate the lesser condition of women as a subclass within these unequal nations.

Wilkinson and Pickett suggest that, rather than comparing “rich countries with poor countries” we should compare rich countries and then look inside them to see how well they are actually looking after their people.

Within countries like Japan and some of the Scandinavian countries … the richest 20 per cent of people are less than four times as rich as the poorest 20 per cent of people. At the bottom of the [scale] are countries in which these differences are at least twice as big, including two in which the richest 20 per cent get about nine times as much as the poorest. Among the most unequal are Singapore, USA, Portugal, the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand. (p.16-17)

The book makes no attempt to explain why Portugal should stand out in such a contrast to its continental European neighbours, which almost invariably outperform English speaking countries on equality and social conditions. I would suggest however that one reason lies in Portugal's inheritance laws, which reflect a tendency to disinherit children in favour of spouses, similar to English-style laws. In the other European countries roman-style civil codes provide for children before spouses equally, therefore men and woman come to adulthood with similar wealth.

Wilkinson and Pickett find that the countries with the worst social inequality have the worst social outcomes overall in health, violence, obesity, illiteracy, mental illness, addiction, and rates of teenage pregnancy.

The official message is that developed western countries have done their duty by their own populations in fulfilling their material needs, leaving a remaining task of bringing the poor of other countries up to the same material standard. It seems churlish of people in those first world populations to reproach the rich in their countries for ostentatious and dishonest living, while the poor in the third world suffer malnutrition and disease. The official message is really that the poor of the developed world need to put the needs of the poor of the undeveloped world ahead of theirs, rather than to exert their own rights locally. The normalization of competitiveness over cooperation and social trust is a strategy to justify the growing vast internal inequalities in the first world.

Importantly for Feminism, within these unequal nations there is a further sub-class, and that is the women of those nations.

Female obesity linked to inequality

Most women would be interested to know that the authors, Wilkinson and Pickett, are able to find a clear association between inequality, obesity and the female sex.

The World Health Organisation has found, from a study begun in the 1980s, that in the 26 countries it surveyed, rates of obesity have increased more among poor women than rich women. The countries with the worst inequalities – Australia, the United States, Portugal and the UK, also have the worst rates of obesity. The countries with the lowest rates of inequality have the lowest rates of obesity.(p.98)

Observing a relationship between anxiety and material and social inequality, the authors note that chronic stress stimulates the hormone, cortisol, of which high levels are associated with deposits of fat around the middle.(p.95) People with this kind of fat are at higher risk of other illnesses – notably diabetes. Diabetes is itself associated with depression.

The authors also refer to the concept of the ‘thrifty phenotype’ where birth weights are lower in women who have experienced stress during pregnancy. Are low-birth weight babies likely to squirrel away extra calories because the stress they encountered in utero led them to prepare for a harsh society, where they would expect to struggle for food? Instead, although they do grow up in a harsh society, it is a non-traditional variety where food remains plentiful but love and approval are at a premium. (p.98)

The book also notes that food may stimulate the brain in the same way as addictive drugs do in people who use food addictively. That is, that food may be used as a pain-killer. (p.96)

It is probably obvious that food marketing may also have a role in obesity, but what is that role? The authors find associations between eating for comfort and homely foods which remind people of childhood, but they note that fast food outlets aim to reassure and to provide the lower classes with a feeling of social mobility. They reassure through their reliability and clean surroundings, but they also provide an affordable opportunity to dine out, which was once the province of the rich. Of course when you dine out on fast food, you are taking in huge amounts of calories in the form of fats and sugars, to a degree not found in haute cuisine restaurants.(p.96)

The book also refers to a study which related obesity to people’s subjective sense of ranking low in the social pecking order. That is, how you feel you compare is more important than your absolute living standard.(p.101)

To recapitulate, this book is about how, once the basics are present, absolute living standard is outweighed by social ranking as measured by relative living standard.

Women as a sub-class within unequal first world nations

Importantly for Feminism, within these unequal nations there is a further sub-class, and that is the women of those nations.

In Mary Pipher’s Reviving Ophelia: Saving the selves of adolescent girls, (Riverhead Books, New York, 1994) the subject is also about inequality and anxiety within high GDP, purportedly progressive societies. Despite the rhetoric, she argues, girls receive a consistent message that they don’t deserve equal treatment and must go to outlandish lengths for mere acceptance. For this reason the whole basis of their identities become at risk as they identify as women rather than as children. They learn that their psychological identities depend on the approval of men. This explains the very high rates of anorexia and risky lifestyles among young women seeking some control over their social and personal environments.

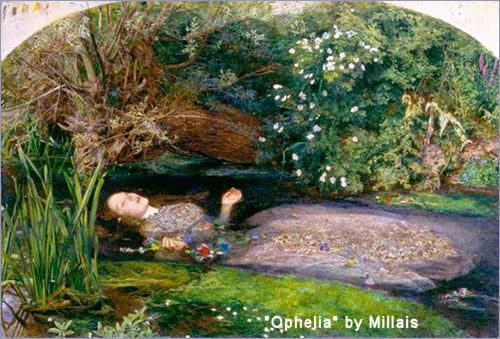

Harking back to Shakespeare’s Ophelia in Hamlet as a young woman who lost the approval of the important males in her life and then suicided, this book observes the increasing difficulty since the 1980s that adolescent girls and the women they become have in preserving a sense of self and self-worth as they transition between childhood and maturity. It finds that they are victims of an increasingly sexualized and pornographic society that defines them almost exclusively as sexual objects, despite the official rhetoric of women’s rights. The girls feel the need to justify themselves against these media popularized and reinforced social standards and, in doing so, to suppress their real feelings and ambitions.

The author observes that, whilst her 1960s generation grew into a western society where the Women’s Liberation movement had overturned official institutional barriers to women’s rights to career, property and political candidacy, the mainstream media preserved, then enhanced over the next decades, a picture of women as inherently less-deserving of these rights than men. Unglamorous, older women (the majority) rarely receive attention in the mass media, and beautiful women often seem only to deserve violent attention, as victims of elaborate predator screenplays. Women are increasingly bombarded by this kind of view at younger and younger ages.

This book, Reviving Ophelia, was published in 1994, at a time when the pervasiveness of the internet was in its relative infancy. Children and the general public were not widely exposed to explicit pornography and sexual sadism in the ‘traditional’ mass media of the industrial age, although these notions were commonly implicit in images and concepts used for marketing all kinds of things. Between that time and now, in 2011, the depiction of women almost exclusively as victims and objects of violence and pornography, explicitly and for that sole reason, has become a global business which operates 24/7. The implicit violence and sexualisation of women in ordinary marketing has also continued. At the same time, the official message is that western women don’t need Feminism anymore because equality has prevailed.

How does a girl, as her sexual personality awakens deal with the saturation marketing of femaleness as moronic and deserving of punishment and death? Mary Pipher argues that girl’s personalities die and that they often die with their personalities.

”Ironically, bright and sensitive girls are most at risk for problems. They are likely to understand the implications of the media around them and be alarmed. They have the mental equipment to pick up our cultural ambivalence about women, and yet they don’t have the cognitive, emotional and social skills to handle this information. They are paralyzed by complicated and contradictory data that they cannot interpret. They struggle to resolve the unresolvable and to make sense of the absurd. It’s this attempt to make sense of the whole of adolescent experience that overwhelms bright girls.

Less perceptive girls may miss the meaning of sexist ads, music and shows entirely. They tend to deny and oversimplify problems. They don’t attempt to integrate aspects of their experience or to ‘connect the dots’ between cultural events and their own lives. Rather than process their experience, they seal in confusion.

Often bright girls look more vulnerable than their peers who have picked up less or who have chosen to deal with all the complexity by blocking it out. Later, bright girls may be more interesting, adaptive and authentic, but in early adolescence they just look shelled.

Girls have four general ways in which they can react to the cultural pressures to abandon the self. They can conform, withdraw, be depressed, or get angry. Whether girls feel depression or anger is a matter of attribution – those who blame themselves feel depressed, while those who blame others feel angry. Generally they blame their parents. Of course, most girls react with some combination of the four general ways.” (p. 43.)

Girls deal with painful thoughts, discrepant information and cognitive confusion in ways that are true or false to the self. The temptation is to shut down, to oversimplify, to avoid the hard work of examining and integrating experiences. Girls who operate from a false self often reduce the world to a more manageable place by distorting reality. Some girls join cults in which others do all their thinking for them. Some girls become anorexic and reduce all the complexity in life to just one issue – weight.” (p.61)

Mary Pipher observes that the loss of confidence in themselves that girls experience as they mature sexually occurs just at the time when more confidence is required to tackle increasingly complex work in the later years of school. Because of this socially-induced lack of confidence, even some highly intelligent girls will give up at the first sign of difficulty, where less bright male students will persist.

The book contains many succinct case histories and concludes with useful ways to approach these problems.

Male treatment of this subject - Turning Angel

How do men deal with these realities that affect their daughters, mothers and intimates so badly? In conclusion, I will mention a book by a man exploring these themes. spirit-level.jpg by novelist, Greg Iles, (Hodder and Stoughton, 2006) is a highly readable thriller that dramatises the stresses of the normalization of sexism and pornography on young girls [and men] in their last years of high school and the particular vulnerability of highly intelligent young women from dysfunctional homes. Iles looks at the temptation for upwardly mobile professional men to exploit such young women. It is also well worth a read and testifies to the continuing usefulness of the novel as a medium for social comment as well as entertainment.

NOTES

[1] Deidre Macken, “I’m starting with the man in the mirror,” Australian Financial Review, September 13, 2011.

An ABC program actually dealing with immigration statistics is fairly rare. But it seems that even some right-wing pro-growth commentators have been raising concern about the statistic that 1544 new migrants are arriving every day. "1544 people who need housing". The IPA, normally a fan of population growth, has suggested that "excessive migration has pummelled Australia's economic productivity".

An ABC program actually dealing with immigration statistics is fairly rare. But it seems that even some right-wing pro-growth commentators have been raising concern about the statistic that 1544 new migrants are arriving every day. "1544 people who need housing". The IPA, normally a fan of population growth, has suggested that "excessive migration has pummelled Australia's economic productivity".

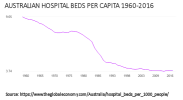

In 1960 Australia had 9.65 hospital beds per 1000 people. This number shrank to 3.84 hospital beds in 2016, with a low in 2013 of 3.74. A very slight increase to 3.9 beds per 1000 people in 2017-2018. Between 1960 and 2021 Australia's population grew from 10.28 million to 25.69 million people. This is a growth of 150.0 percent in 61 years.

In 1960 Australia had 9.65 hospital beds per 1000 people. This number shrank to 3.84 hospital beds in 2016, with a low in 2013 of 3.74. A very slight increase to 3.9 beds per 1000 people in 2017-2018. Between 1960 and 2021 Australia's population grew from 10.28 million to 25.69 million people. This is a growth of 150.0 percent in 61 years. It is surprising to pick up a book about wealth statistics and find that it segues so readily into another about psychopathology in young girls. The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone takes a revealing look at how wealth is distributed within different developed countries and Reviving Ophelia illustrates the decline of women's rights in the face of aggressive pornography and its effect on girls. Children and the general public were not widely exposed to explicit pornography and sexual sadism in the ‘traditional’ mass media of the industrial age, although these notions were commonly implicit in images and concepts used for marketing all kinds of things. Between that time and now, in 2011, the depiction of women almost exclusively as victims and objects of violence and pornography, explicitly and for that sole reason, has become a global business which operates 24/7. The implicit violence and sexualisation of women in ordinary marketing has also continued. At the same time, the official message is that western women don’t need Feminism anymore because equality has prevailed.

It is surprising to pick up a book about wealth statistics and find that it segues so readily into another about psychopathology in young girls. The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone takes a revealing look at how wealth is distributed within different developed countries and Reviving Ophelia illustrates the decline of women's rights in the face of aggressive pornography and its effect on girls. Children and the general public were not widely exposed to explicit pornography and sexual sadism in the ‘traditional’ mass media of the industrial age, although these notions were commonly implicit in images and concepts used for marketing all kinds of things. Between that time and now, in 2011, the depiction of women almost exclusively as victims and objects of violence and pornography, explicitly and for that sole reason, has become a global business which operates 24/7. The implicit violence and sexualisation of women in ordinary marketing has also continued. At the same time, the official message is that western women don’t need Feminism anymore because equality has prevailed.

Recent comments