*NEW*: The Dirty War on Syria: Washington, Regime Change and Resistance (PDF)

- ISBN Number:

- 978-0-9737147-7-7

- Year:

- 2016

- Product Type:

- PDF File

- Author:

- Tim Anderson

Humans have a magnificent brain, one that even while at rest churns through more information in 30 seconds than the Hubble space telescope has processed in thirty years. In fact the brain absorbs so much data it also has to decide which is relevant and which to ignore, a feature that makes us terrible witnesses.

Humans have a magnificent brain, one that even while at rest churns through more information in 30 seconds than the Hubble space telescope has processed in thirty years. In fact the brain absorbs so much data it also has to decide which is relevant and which to ignore, a feature that makes us terrible witnesses.

In The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia (2011), Bill Gammage argues that Aboriginal Australians shaped the continent’s vegetation landscape through firestick farming, a sophisticated practice of deliberate, low-intensity burns to create open, park-like grasslands and resource-rich environments, challenging the notion of a “natural” pre-European landscape [11].

In The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia (2011), Bill Gammage argues that Aboriginal Australians shaped the continent’s vegetation landscape through firestick farming, a sophisticated practice of deliberate, low-intensity burns to create open, park-like grasslands and resource-rich environments, challenging the notion of a “natural” pre-European landscape [11].

Nils Melzer’s book about the persecution of Julian Assange – Nils Melzer, The Trial of Julian Assange, A story of persecution,[1] must be heeded, due to Melzer’s extraordinary position and status as an independent international investigator and legal expert in complaints of torture and ill-treatment, [2] which has given him access to details and documents not previously available. That is probably why it is hard to get the book in Australia.

Nils Melzer’s book about the persecution of Julian Assange – Nils Melzer, The Trial of Julian Assange, A story of persecution,[1] must be heeded, due to Melzer’s extraordinary position and status as an independent international investigator and legal expert in complaints of torture and ill-treatment, [2] which has given him access to details and documents not previously available. That is probably why it is hard to get the book in Australia.

Her Majesty the Queen is sitting on top of an explosive pile of stinking manure. Nils Melzer's book is like a bomb about to go off. How long can crooked judges and governments hide? How long can the mainstream press pretend that nothing's happening?

Her Majesty the Queen is sitting on top of an explosive pile of stinking manure. Nils Melzer's book is like a bomb about to go off. How long can crooked judges and governments hide? How long can the mainstream press pretend that nothing's happening?

It's not an easy life described within the covers of Donna Ward's semi-autobiography, She I dare not name: A spinster’s meditations on life, Allen and Unwin, NSW, 2020. In a vocabulary measured with precision but rich with imagery, Ward evaluates her experiences as an unmarried woman who achieved this status without wanting it at all. The book is very honest in its descriptions of how this came about and the importance that it has in defining the course of Donna’s life. The term "spinster," is initially called up like some daemonic creature. It is something she almost dare not name! As we read on, we realise that spinsters are not gothic inventions, but human like their married counterparts, probably equally defined by hazard.

It's not an easy life described within the covers of Donna Ward's semi-autobiography, She I dare not name: A spinster’s meditations on life, Allen and Unwin, NSW, 2020. In a vocabulary measured with precision but rich with imagery, Ward evaluates her experiences as an unmarried woman who achieved this status without wanting it at all. The book is very honest in its descriptions of how this came about and the importance that it has in defining the course of Donna’s life. The term "spinster," is initially called up like some daemonic creature. It is something she almost dare not name! As we read on, we realise that spinsters are not gothic inventions, but human like their married counterparts, probably equally defined by hazard.

It seems to be a case of pot luck that brought Donna to the point of which she writes, in a book finished in her sixty-seventh year.

Donna describes early years rich in experience of nature and travel, warm relationships with larger-than-life parents, and the birth of a young sister in her early childhood. This was however an event notified by her father, only one day prior, with something like sexual shame.

“He said this as if he barely understood anything about it , as if it was something Camille and Mum had cooked up between themselves that very day , something so shameful he’d had to fly all the way home to sort it out, though I didn’t think he was doing a good job of it.”

Mostly, however, her account of her childhood reads almost like a comforting and exciting slide show with non-sequential images and vignettes, depicting mostly carefree recollections. One senses though, that Donna’s parents are involved with each other more than they are with Donna, and that their relationship with her has conditions attached. In primary school, Donna experiences a “desperate relationship with spelling and arithmetic,” to the extent that she is sent to a psychiatrist. No-one can determine whether she is “brilliant or dumb.” Her mother cannot hide her shame from Donna. By the time Donna is ten, though, she is a good student.

It's in adulthood that the going gets really tough. Donna also indicates that she has a very poor relationship with her sister. Where she might have expected to benefit socially in many ways, from an introduction into her parents' well-connected circle in WA mining world, instead, having chosen to do social-work, she is marked as an outsider.

Ward moves from Perth, Western Australia, to Melbourne, Victoria, as a young woman, and predictably has to make her own way in the big city. She shares houses but mostly lives alone. She goes to university and gains her degree. She lands her ‘dream job’ but loses it to a male in the ‘recession we had to have’, as it was termed by the then Federal Treasurer Paul Keating, in 1990.

This job-loss was probably a defining point in Donna’s personal development. Where professional status might have compensated an early lack of unconditional love and brought her earning capacity and social rank up to something recognisable to her former peers, her job-loss plunges her into indeterminate socio-economic status. In parallel with other isolated social and economic victims of economic rationalism, she must individually craft a new survival path. She achieves this with difficulty, an exotic traveller in the new age, finally emerging as a neo-classical philosopher on non-marriage.

Descriptions of her social encounters give the reader a sense of her tumbling around in a sea of strangers interspersed with special friends and lovers poetically anonymised for publication as archetypes or as characters in Ancient Greek tales. Our heroine or protagonist does her best with what she encounters. The life she grapples with is one that has no markers or guideposts and she feels herself to be at the mercy of the preferences of the males she becomes involved with, or the narrative they see for their lives, with respect to other female players. Then again, it was she who decided not to go through with marriage to a Japanese fiancé. In her chapter, ‘The Weight of a child’, we glimpse another of life’s cul-de-sacs as she briefly recollects terminating a pregnancy that resulted from rape.

“I could not have that child, the conception had been so rude. The way his father pushed me onto the couch, held me at the throat, tore my panties and took his revenge, took what I had denied him years before. […] In the autumn of 1977, when the jacarandas were yellowing and the plum trees sapping their leaves, I let that child go, lest I be tied to his father for the rest of my life. I believed another child would come along. (Ward, Donna. She I Dare Not Name: A spinster's meditations on life (pp. 248-249.)

No-one seems to be looking out for Donna, our heroine. She just has to take it on the chin. Is this a failing of her character or is it due to the milieu and time she finds herself in? We found her a very likeable character. In many ways we were reminded of our own photogenic childhoods with happy pictorial vignettes bathed in yellow light, freedom, and cosiness, along with similar struggles in adulthood.

This narrative raises the question: How does a young woman in a big city, away from her parents and her natal community, find love, or find that suitable person with whom to form a family? It is clear from Ward's writing that that her drive to ‘nest’, to be part of a couple (duo), and to have a child, is very strong. It seems both hormonal and social. She wants to be part of the world of couples, to alleviate loneliness, to find security, and to change her status. In the face of disappointment, she soldiers on courageously, but her essentially solitary situation – despite friends and jobs - makes her vulnerable to predatory or incompetent approaches.

She mentions serial recoveries from the emotional hurt of broken relationships. Is life really meant to be so hurtful and stressful? Many women and men would relate to the bruising nature of the relationship-seeking process in the 20th and 21st century urban social environment.

The author describes her experiences, starting in the 1970s until the present. Dating is one way we do this in the West. Both parties do a series of interviews over dinner and this process can go on for years. There are more casual opportunities in which to evaluate potential partners, such as clubs with shared activities, like tennis, bushwalking, or Meetups; churches, political groups, universities, and work. A friend of mine met her life-partner and husband through an ad in a ‘singles magazine’ in the 1980s. These days she might have found him via internet dating services.

The quest for a mate is not a level playing field between men and women if they want children, as the woman is almost invariably up against time constraints. These constraints become increasingly urgent as she moves from her twenties to her thirties. A woman has a brief period in her life from about age sixteen to twenty-five, when she is most sought after by men her own age as well as those considerably older. In terms of sexual attractiveness, she has the odds in her favour then, more than she will have at any time in the future.

If she misses this opportunity to light on the ideal partner, or at least a suitable one, she has her work cut out. It will dawn on her gradually, as she approaches thirty, that really there is not much time and there is a decreasing number of men to choose from.

The finishing post in this ‘race’ is usually considered to be forty, after which a woman will not necessarily expect to ever conceive. If she wants to and she does, it will be a bonus in any permanent partnership she manages to secure.

The woman is, as was Donna Ward, expected, under this pressure, to make a wise assessment of the men who cross her path, to get to know them better than superficially, and to try not to get hurt. Whether she will have descendants depends on how she negotiates this situation. Adding to the difficulty of the task, in her most propitious years, she is necessarily young and inexperienced.

How could our society better provide a benign environment for young marriageable people to meet in relative safety? Should mothers give guidelines to their daughters as to how to as to how to negotiate the situations they will face? Did most mothers also have to just find their way through the minefield? Did they think, "Well I had to do it, and my daughter now faces the same challenge!"

Do most of us leave this all-important decision to complete chance? The writers' parent’s generation, reaching adulthood in the 1940s, were more connected, and their parents more so. They did not often travel far or without introductions. They grew up in more predictable communities with pathways to identifiable milestones (rites of passage) and traditions, and relatives and connections, for negotiating these. At the same time, in the Anglosphere and Europe, in the 1950s and 60s, a burgeoning manufacturing industry meant plentiful jobs. An explosion in energy resources and transport allowed people to commute by car to work, from affordable housing in new estates on land once out of reach. That meant more people could move out of home, get a job, and get married. It was called the Baby Boom. Unfortunately, the explosion just kept magnifying and accelerating globally until mass transport and travel broke time-worn connections, dispersing people, at ever increasing speed to the four winds, far away from the familiar pathways, milestones and traditions.

Thus, our heroine dispersed like a dandelion seed and landed in Melbourne, apparently without any significant connections, in a city with diminishing social capital.

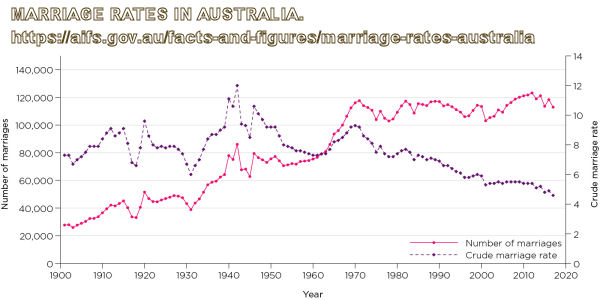

Did most women of her generation negotiate the getting hitched and having children part successfully - if not forever or until ‘death us do part’ - at least for long enough to have a child or two? Why did some, like our heroine miss out, or was the experience more common than we may think? Good luck finding statistics on how many women die without having children. As you can see from the graph, the unmarried proportion of the population has been steadily increasing since the 1970s oil-shock.

Maybe those who did not partner for long enough to have at least one child lacked the connections to find a suitable partner. This seems to be the case with Ms Ward. Many of her encounters with men seem accidental, lacking formal introduction or context, and so she lacks essential information. In assuming reciprocally honest interactions, she is fooled, more than once, by men who are thus easily able to conceal the fact that they are already partnered. Positive tit-for-tat, where good deeds and bad deeds are quickly reciprocated is only possible in viscous societies, where people stay close to where they originate from. Melbourne’s population is close to thirty-five per cent diaspora. Another way of saying this is that people can get away with breaking trust in an anonymous or constantly changing population, unless they belong to a stable enclave within it. Donna didn’t.

A major part of Ms Ward's serial emotional recoveries from serial romantic disappointments come from the blow to her self-esteem, because she mistakenly believes that there must be some flaw in herself, invisible to her, but which these men can see.

A more informed perspective might explain, however, that Ms Ward is a stranger trying to make her way in foreign territory, where her pedigree is unknown, where she has little or no personal status. She does not read the signs accurately or speak the local social language fluently. She is proceeding using signs she learned in West Australia for a small network there, which has probably gone extinct. She did not avail herself of that network when she was in West Australia because she had different values from her parents. This was because she came from a different generation at a time when values were changing rapidly. In her case, Aboriginal rights and Germaine Greer were (by her account) two contemporary changes that obviously influenced her and helped to separate her from her origins. The first affected her relationship with her mining father, and the second affected her relationship with men more generally.

Apparently, she did not want to be part of the money and status oriented, environmentally exploitative, mining crowd her parents belonged to. So, she migrated from West Australia to Sydney, then Melbourne. She acquired some social credentials and connections from universities there, but they were not enough to establish her as a local candidate for the kind of marriage she wanted. She found a good job, but the 2008 recession removed that job, so what were her prospects? We don't know. Having a house is certainly a plus, if you want to attract a mate, but, although she seems to have a house, we do not know how big her mortgage is. She would have needed to be careful not to marry someone with lesser prospects, for fear of being impoverished by divorce, and that would rule out a large and growing demographic.

Ms Ward seems to assume that marriage must have its basis in love. Most people want to marry up and for love, and most who marry say they did marry for love, but how many really do? Is the number of divorces an indication?

Since Ms Ward seemed to have limited opportunities, for one reason or another, perhaps she could have ranked her priorities differently. Reading closely, her real priorities might have been marital status, children, and companionship. Unfortunately, she seemed to put love up at the top. Love is a western ideal but, unless you are very lucky, that is a musical chair game that leaves many more standing than seated, and childless if they persist as the stakes go up. It might be better to look for respect and kindness. Love might come later, and, if it doesn't, affairs within marriage are the tried and true solution.

It is easier to understand the problem of partnership in the west, if you imagine that you are arranging a marriage for someone in 19th century England or in 20th century India, where your parents work out early where you are situated with regard to income expectations and earning, education, charm, and physical attributes. Although your parents might use marriage brokers, it is still likely that they will employ those brokers to find someone within their circle, or at least within a similar circle. When they find a candidate, each set of parents checks the other out for compatibility. After that they decide whether or not to let the children meet.

Given that parents do not generally perform this role as explicitly in contemporary Western society, many young women have to fend for themselves. Perhaps a way women (and men) could try to look after their own interests better could be by cultivating a perspective as if they were their own in loco parentis. Such a perspective would indicate a major change in the concept of marriage in Australia.

This book aims to talk truth to power, using intersectionalist feminist concepts, within the strange paradigm of the corporate newsmedia [1] and US-NATO foreign policy. Power is identified as whiteness. White women are enjoined to stand with women of colour against male whiteness, which they are charged with propping up for their own benefit.

This book aims to talk truth to power, using intersectionalist feminist concepts, within the strange paradigm of the corporate newsmedia [1] and US-NATO foreign policy. Power is identified as whiteness. White women are enjoined to stand with women of colour against male whiteness, which they are charged with propping up for their own benefit.

Whiteness is defined as non-brown and non-blackness. But brown-ness can include whites who are not the ‘right kind of pale’.

“Whiteness is more than skin colour. It is, as race scholar Paul Kivel describes, ‘a constantly shifting boundary separating those who are entitled to have certain privileges from those whose exploitation and vulnerability to violence [are] justified by their not being white.’” [2]

Hamad accuses white women in Australia today of endorsing non-white slavery and colonialism now and through the ages because they benefited and benefit from it. She writes as if the accused white women are conscious that their attitudes condone such slavery. I would say, however, that the class that endorses these things that are decided by their ‘betters’ does so because its members believe the government and corporate media spin that justifies war, colonialism and exploitation of peoples far away. The women (and men) in the classes the system still works for, or who believe it still works for them, are obedient and unquestioning of authorities anointed by these. Such people erupt in defence of media-anointed authorities they believe to be pillars of virtue. They will also hotly defend the ideas and values they receive from these classes.

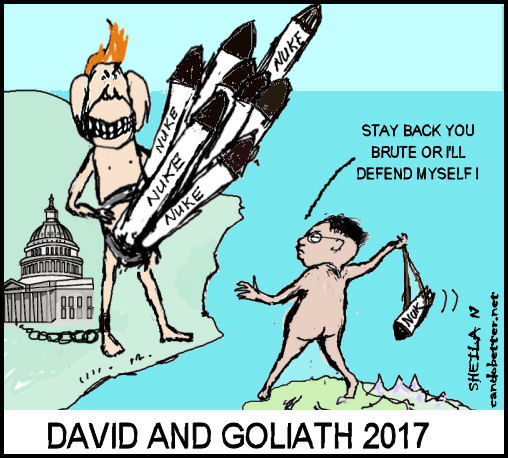

Of course, various forms of psychopathic entitlement underlie the public rationales of our leaders for colonialism and wars. These include xenophobic assumptions or just contempt for anyone standing against what empire builders and weapons lobbies want. You would think that anyone could see through these, but they don’t. Obedient Australians respond viscerally to their masters, on whom they depend, like good dogs conditioned by rewards and punishments. Hence they easily fall for the suspicious perpetual recurrence of ‘mad and brutal dictators’ in the Middle East, whom the west must get rid of through regime change. As Dr Jeremy Salt, Middle-East scholar says to cartoonist Bruce Petty (who visited Syria in 2011) in the video below (which I made), "There always has to be a madman in the Middle East" [so that the west can have an excuse to invade.]

The greater basis for their credulity is apparently the idea that the Middle East has not ‘developed’ sufficiently to achieve lawful societies, in part because it is religiously divided and lacks the separation of church and state. No relevant history is provided by the newsmedia as to how these things came about in formerly very stable societies.

Additionally, the newsmedia seems to report on overseas 'interventions' in the most confusing manner possible, as it also does with Australian politics. This leaves the Australian classes that rely for information on the newsmedia with the idea that domestic and foreign politics are incredibly complicated and hard to follow. Bored and helpless, they see no choice but to place their faith in the imagined greater intellects of the journalists and politicians involved in producing this atrocious spin.

I find it difficult, however, to agree with the assumption in Hamad’s argument that all white women (and men) in Australia accept the doctrine of the newsmedia. There seem to be plenty of men and women in Australia who question war, invasion, mass population movements, Julian Assange's imprisonment for exposing war-criminals, and think that sovereignty should be respected, but they don't find any clear echo in the newsmedia, except sometimes in masses of negative comments on line, especially on articles promoting population growth. Those commenters cannot, however, get in touch with each other to organise. Constant demographic, employment, and land-use changes have also interrupted traditional family and neighbourhood networks, and big business has taken over the universities, as the newsmedia has taken over the public talking stick. So, if you believe that the newsmedia represents the opinions of most Australians, as Hamad seems to, I think you would be wrong.

There is still an anti-war movement, but it is very disorganised, almost certainly because the mainstream media ceased to report its point of view leading up to and after the invasion of Iraq. [3] The anti-war movement exists in the alternative media, both Australian and overseas. (See IPAN (and here) for instance.) Unfortunately, spontaneous voluntary movements using independent and big tech media resources still do not have nearly the same publicity reach of the newsmedia nor the power to authoritatively self-anoint. The Facebook tech-machine geographically limits Australians to Australia when using its promotion system (ads) for criticism of corporate newsmedia talking points and government policies (especially those of the US). They thus continue to be drowned out by the internationally syndicated newsmedia. The greater public, whose smart screens and phones are still commercially tuned to the corporate newsmedia are thus not aware of these other views. They are only aware of them if they use independent search engines, since smart phones and screens have licence restrictions on what they can show. Whilst it is easy to simply put a URL in a browser, most people don’t know this and children are not even taught it. They might use search engines to look for alternative reports, but they are not aware that the license restrictions of the commercial software associated with their ‘smart’ electronic hardware, keep their information sources nearly as narrow as the pre-internet era.

But Hamad is a professional newsmedia journalist. Not only is she a newsmedia journalist, but she refers to what passes for Australian cultural belief and 'leftist' values in the newsmedia as if these were actual reflections of most of Australian society, rather than a sort of echo-chamber for the classes that read and write in them. Does she really believe in the cultural matrix that she refers to, or is she merely using its own language to question it?

Of particular interest to me was Hamad's experience in questioning Australia's support for US-NATO military intervention in Syria. If you weren't already aware of the shocking wrongness of our policy towards Syria, then you might wonder what Hamad is talking about here.

Hamad, who comes from a Lebanese and Syrian background (Greater Syria), and who still has relatives in Syria, describes how she was rebuffed when she tried to express her disapproval of a US intervention in Syria to her feminist white colleagues.

"[Syria] is such a fraught issue that genuine discussion is impossible while smears and misplaced outrage are the norm. On this occasion in early 2018, I felt compelled to say something as it was the day after US president Donald Trump launched strikes on Damascus following an alleged chemical attack on a rebel-held town. Anna [her Anglo-Australian friend] expressed support for the strikes in a post, which I found jarring, and I told her - calmly - that I was confused given that the United States' act signalled a possible escalation of the conflict and further suffering. I was rebuffed as an aggressor who was hurting her and had to be publicly humiliated for it: the damsel requires her retribution. Merely by letting Anna know that although I understood she cared for Syrian civilians, her stance was disappointing to me, I inadvertently unleashed a demonstration of strategic White Womanhood that brushed aside the actual issue - the air strikes - and turned it into a supposed attack by me on her 'just for being white'. The result was a torrent of abuse hurled at me on a Facebook thread." (Pp105.)

Hamad’s analysis of this exchange is that, rather than deal with the political issue of bombing Syria and the atrocious consequences of war, [Anglo-Australian] Anna seemed to interpret the questioning of Hamad’s views on foreign policy as an attack on Anna for being 'white'.

Hamad sees this as a way of avoiding the issue. She thinks that the motive for avoiding the issue is to preserve the status quo from which White Womanhood benefits.

I think this analysis would work better if we substituted the word 'consequence' for motive, because it is hard for me to believe that most Australians who defend US-NATO policy towards Syria do this with a conscious understanding of the issues. Unless they are actually heads of government/ selling weapons, of course.

Where would they acquire such an understanding? Only by venturing beyond the Anglosphere and Eurosphere mainstream, but they have been repeatedly and explicitly conditioned to avoid alternative perspectives like RT and Presstv Iran, and the many independent blogs, in various languages, as ‘fake news’ by that very mainstream. It’s effective wedge politics; middle class Australians hardly dare look over at the other side of the fence on any issues. And, as mentioned, their smart screens have licensing issues.

It is true, however, that by blindly defending official policies, the obedient classes defend that tiny power-elite that pursues those policies consciously and pollutes our public messaging system with false reasons for war.

But, you see, I have encountered just the same kind of reaction when I have criticised military intervention in Syria. My friend’s father expostulated that we were ‘extremists’ and accused his son of falling for ‘fake news’. Mainstream journalists regard you with horror and abhorrence. On-line such views are treated as highly eccentric and laughed at, except when sympathisers find them. Most people you meet have no idea whatsoever about what you are referring to.

Politicians claim not to know anything about foreign affairs or they ignore you. I would have liked it if Hamad had gone to the role of Australia's then foreign policy minister, a [white] woman - Julie Bishop - in officially supporting US policy in Syria. Along with others, I wrote to Bishop about this, but received absolutely no response. And I wrote an article about the absurdity of it all: "Can Trump dodge his deep state destiny by acting absurdly?" Now it is quite possible that Julie Bishop had no idea of the consequences of what she was supporting, but she had direct responsibility, and a duty to inform herself. The reason I would like Hamad to address the role of a successful white female politician on Syria is because such people are elected and propped up via the false rhetoric of the newsmedia. That is how the normalisation of aggression against Syria takes place.

I know also that Syrians who hold the same attitude as me often don’t dare express it in public, and sometimes among Syrian acquaintances. Why is this? One reason is that refugees from Syria are more likely to receive encouragement from the Australian government if they say that the Syrian Government is a brutal dictatorship, even if they don’t really think so, since that is the official opinion of the Australian Government. And I have been told that quite a few Syrians in Australia actually do sympathise with the so-called Rebel armies in Syria, and so you might think twice about denouncing them or even disagreeing with them. New Zealand, our close neighbour, has settled some members of what many believe is a fake Syrian rescue group, with ISIS sympathies,the White Helmets. [4] Whilst I agree with Hamad that bombing Syria was a terrible idea, note that I am not saying that Hamad holds the same views on Syria as me. She does not actually disclose her views in her book.

It also sounds as if ‘Anglo-Australian’ Anna was out of her depth and was responding to a loss of ‘face’ on Facebook. That Anna then accused Hamad of being racist towards her is for me a symptom of Australia’s contamination with US race-baggage, not surprisingly, because of massive syndication of Australian newsmedia with US newsmedia, which virtually blots out Australia itself.

Whilst it is true that Australia was founded on the dispossession and genocide of non-white hunter gatherers, with some enslaved, others religiously indoctrinated, its initial principle labour source was convicts from the Irish, Scottish, Welsh and English lower classes. Most of these people would, however, meet Hamad’s definition of non-white, because land-tenure and inheritance law disqualified them from white power. They came from a country of severe class division. People there stole in order not to starve. As an example, the numbers of Irish transported soared with the Irish potato famine, due to crimes committed from hunger. [5]

Numerous convicts were charged with sedition and similar crimes and sent here as punishment for agitating for democratic government. [6] Many Irish were transported for insurrection due to their participation in revolts against the English. Convicts had no rights and could die in brutal conditions. [7]

Transportation of revolutionaries and protesters to the ends of the earth was an extreme form of demographic and political atomisation in Britain. Australia was Britain’s gulag and she sent a lot of people there who might otherwise have made a greater difference to British politics. Many recent Australians and mainstream journalists seem to have no knowledge of this or of the biophysical limitations of this continent. [8]

We do Australia a disservice if we fail to remember that people in this country initiated the Eight Hour Day, and stopped the beginnings of a slave-trade in Pacific Islanders and outlawed that of other ‘non-white’ peoples.

Australian workers at the turn of the 19th century, having ended transportation of forced ‘white’ labour, noting the kidnapping of Pacific Islanders, also rejected ‘non-white’ slavery through the White Australia policy, which was a trade-off for allowing manufacturers to import foreign goods. [9] Worker reasons for this would have been economic, since unpaid work presents unfair competition to free people. Unsurprisingly, just as today, we have little record of what ordinary people had to say on the matter, however. The rhetoric that we retain from the time is, of course, only from elites. Even among the elites, there was a fair amount of abolitionism, especially regarding the cessation of convict labour. The lack of contemporary documentation has made it easy to promote a view of the White Australia policy as a kind of Nazi doctrine, but it is dishonest to omit the anti-slavery and industrial relations aspects.

Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch of 1970, galvanised the Australian and international feminist movements, completely redefining how women saw themselves. Yet today Greer is hardly mentioned in the revisiting of feminism. Between 1972 and 1975 the Whitlam Government promoted multiculturalism, birth control, and feminism in the general population. These values were widely adopted in the generation now called ‘baby boomers’. Bizarrely and unfairly, recent anti-racist and mainstream feminist promotions fail to recognise, let alone build, on these well-established Australian values.

It might achieve more if articulate people like Hamad would look, beyond the mainstream representation of Australia, for similarities, rather than differences with their fellow citizens. She writes of the battle for land-rights (p.216). We need her help, because the colonisation is ongoing here. The fight for land-rights is being lost in Australia to the ultra-rich. Other Australians are fighting many different battles to resist our leaders’ addiction to war and growthism, and to preserve this beautiful country and its beleaguered ecology against land-speculation, overdevelopment and overpopulation. But they are being drowned out by the massive volume of the mainstream corporate media, which assails us all with growthist propaganda day and night, and also accuses us of racism, with the effect of shutting up criticism of absurdly high rates of immigration. As well, by appearing to champion or demonise refugees and asylum-seekers, it takes the public debate away from the regime-change wars that generate these.

Hamad argues within what I see as an anthropocentric, black-white, pseudo-‘progressive’ paradigm, without biophysical reference points. Although, at the end, she questions the idea of chronological progress, she still seems to accept the paradigm that we are all ‘going forward’, although no “progress is ever assured”. The points of reference in her universe are largely human-notional, generalised and global, whereas I look at how humans interact with their biophysical environments within specific land-tenure and inheritance systems. Along the same lines as Walter Youngquist’s paradigm in Geodestinies, I see material wealth, war, and colonisation, as a reflection of geology and geography.

I have a land-tenure and inheritance system explanation for the British class system and its production of great quantities of landless labour, which fed into a fossil-fueled coal and iron industrial revolution that permitted Britain’s industrial-scale exploitation of other countries. (See Sheila Newman, Demography Territory Law 2: Land-tenure and the origins of capitalism in Britain, Countershock Press, 2014.)

In Europe one tribe enslaved another. The Romans enslaved the British. Six hundred years later, the Normans reduced much of the British population to serfdom. They imposed almost universal male primogeniture in England, which meant that English women relied on men due to their inability to inherit land, and the bulk of children were effectively disinherited.

The British practised colonisation, mass migration, and genocide of Catholic whites in Ireland, and despoiled that land, with Henry VIII and Elizabeth I egging on the removal of nearly every tree for wood. Cromwell awarded Irish land to his English soldiers.

Many times the Irish Catholics tried to free themselves from the English, finally rising in revolt in 1798, causing civil war.

The civil war was dogged by savage sectarian differences which added their own violence to the government’s ghastly atrocities. Many Irish Ulster Protestants sided with the British. [10]

Irish Revolutionary leader, Wolfe Tone, described a landscape “on fire every night” (from burning houses), echoing with ‘shrieks of torture’, where neither sex nor age were spared, and men, women, and children, were herded naked before the points of bayonets to ‘starve in bogs and fastnesses’. He said that dragoons slaughtered those who attempted to give themselves up as they put down their weapons, and, finally, he talked about the spies who had brought the Irish Revolution down.

“And no citizen, no matter how innocent and inoffensive, could deem himself secure from informers.” [11]

I think that Hamad’s lack of recognition of inter-white racism/classism prevents her from realising that Australia is being recolonised, with ‘diversity’ as the excuse and induced racial schisms as the mechanism to alienate the ‘diverse’ from the incumbent population, the better to over-rule democracy. Australians, despite multicultural policy from Whitlam's time, are stigmatised as white and racist. There is a token nod to Aborigines, whose defining culture can in no way benefit from mass immigration or the 'developed' economy.[12] Hamad is not alone in this complacency because the mass-media constantly massages high immigration and renormalises terra nullius. Hamad has some recognition of this ‘irony’, however.

“I’d be lying if I said I knew how to reconcile all of this. I’m well aware that whatever our own experiences of colonisation and racism-induced intergenerational trauma, non-Indigenous people of colour in Australia are also the beneficiaries of indigenous dispossession. We too live on and appropriate stolen land.” (p.195)

Much of the foreign intervention in Syria has been in order to force it to accept globalisation, privatisation, and leaders sympathetic to these. The same thing is being forced on Australia, but without the need for overt violence so far because, unlike Syria, Australian leaders have not resisted this. And the newsmedia has given no voice to those who are trying to resist it, so they appear invisible.

On a more personal note, I sympathise with Hamad’s experience dealing with frizzy hair during her teenage years (p.180). I had the same problem. I had a different method, which did the same job. I didn’t brush my hair dry for hours, I wound it round my head tightly and fixed it painfully with bobby pins and other clamps, waiting hours for it to dry. I gave up swimming for years, although prior to becoming aware of my appearance, I had swum daily. This was a great sacrifice. Although I was also trying to meet the prevailing standards, which seemed to me to be straight hair, unlike Hamad, I did not identify straight hair with being ‘white’. I was ‘white’ if you like, although descended from Irish, Scottish, and Welsh stock, just not in the ‘in’-crowd as regards hair – or many other things.

A theme in Hamad’s book is that White Women get cross if you challenge their cultural ideas. They shut you out. Hamad has shown that some of these cultural ideas are probably immoral, and she wonders why she is shut out for exposing them. The thing is that all cultures want to control their ideas from the inside and they reject outside challenges. That’s poesis. Basically, to be one of them, you have to embrace their ideology.

Then, within that culture, there are sub-cultures, and cliques. In Australia’s hard new society where seniority and local labour have been dropped and ‘meritocracy’ prevails in an increasingly precarious employment market, women tend to form groups led by the woman closest to power – often a male boss. One of the ways for the dominant women to keep order and stay at the top is to punish anyone who looks like getting close to power by pretending to have been victimised. Another way is to harp on differences, of which ‘race’, ethnicity, religion, hair-type, weight, dress, and opinion, etc are all signs that can be used to define their possessor as a member of the out-group.

This kind of behaviour is also called ‘bullying’. And it is getting worse, unfortunately. Maybe it is a reflection of the way our leaders behave and the economic rationalist anti-society they have forced on us. There is competition out there for food and power. And we are apes.

[2] Ruby Hamad in her Author’s note, p.xiii.

[3] “After the enormous demonstrations against the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the anti-war movement disappeared almost as suddenly as it began, with some even openly declaring it dead. Critics noted the long-term absence of significant protests against those wars, a lack of political will in Congress to deal with them, and ultimately, apathy on matters of war and peace when compared to issues like health care, gun control, or recently even climate change.” Source: Harpootlian, Allegra, US Wars and military action: The New Anti-War Movement, https://www.thenation.com/article/tom-dispatch-new-anti-war-movement-iraq-iran/.

“Criticism of the news media’s performance in the months before the 2003 Iraq War has been profuse. Scholars, commentators, and journalists themselves have argued that the media aided the Bush administration in its march to war by failing to air a wide-ranging debate that offered analysis and commentary from diverse perspectives. As a result, critics say, the public was denied the opportunity to weigh the claims of those arguing both for and against military action in Iraq. We report the results of a systematic analysis of every ABC, CBS, and NBC Iraq-related evening news story—1,434 in all—in the 8 months before the invasion (August 1, 2002, through March 19, 2003). We find that news coverage conformed in some ways to the conventional wisdom: Bush administration officials were the most frequently quoted sources, the voices of anti-war

groups and opposition Democrats were barely audible, and the overall thrust of coverage favored a pro-war perspective. But while domestic dissent on the war was minimal, opposition from abroad—in particular, from Iraq and officials from countries such as France, who argued for a diplomatic solution to the standoff—was commonly reported on the networks. Our findings suggest that media researchers should further examine the inclusion of non-U.S. views on high-profile foreign policy debates, and they also raise important questions about how the news filters the communications of political actors and refracts—rather than merely reflects—the contours of debate.” Source: Hayes, Danny and Guardino, Matt, Whose Views Made the News? Media Coverage and the March to War in Iraq, Political Communication, Vol. 27, No. 1, Dec 2009, p59. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/10584600903502615

“As the [Iraq] war dragged on, and as reporting got better and better, the real problem with news from Iraq would turn out to be how little of it most Americans ever saw or heard. Across the board, as documented by Pew and others, the percentage of the news hole devoted to the war declined steeply.” Source: Murphy, Cullen, The Press at War, From Vietnam to Iraq, Atlantic Monthly, March 20, 2018.

https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/03/iraq-war-anniversary/555989/

[4] Independent journalists who have criticised this US and UK-funded and Hollywood-iconified group have been vilified by the mainstream, but the evidence is out there. See, for instance, Rick Sterling, “The ‘White Helmets’ Controversy,” Consortium News,

July 22, 2018”https://consortiumnews.com/2018/07/22/the-white-helmets-controversy/

[5] Lohan, Rena, Archivist, ‘Sources in the National Archives for research into the

transportation of Irish convicts to Australia (1791–1853)’ National Archives, Journal of the Irish Society for Archives, Spring 1996 https://www.nationalarchives.ie/topics/transportation/Ireland_Australia_transportation.pdf

[6] Convict Records, British Convict transportation register made available by the State Library of Queensland, Various crimes were assigned to revolutionaries, including sedition and insurrection which included many Irish who participated in rebellions. I08 are listed in the Convict Records simply as ‘Irish Rebels’: https://convictrecords.com.au/crimes/sedition https://convictrecords.com.au/crimes/irish-rebel

[7] “During the first 80 years of white settlement, from 1788 to 1868, 165,000 convicts were transported from England to Australia. Convict discipline was invariably harsh and often quite arbitrary. One of the main forms of punishment was a thrashing with the cat o’ nine tails, a multi-tailed whip that often also contained lead weights. Fifty lashes was a standard punishment, which was enough to strip the skin from someone’s back, but this could be increased to more than 100. Just as dreadful as the cat o' nine tails was a long stint on a chain gang, where convicts were employed to build roads in the colony. The work was backbreaking, and was made difficult and painful as convicts were shackled together around their ankles with irons or chains weighing 4.5kg or more. During the day, the prisoners were supervised by a military guard assisted by brutal convict overseers , convicts who were given the task of disciplining their fellows. At night, they were locked up in small wooden huts behind stockades. Worse than the cat or chain gangs was transportation to harsher and more remote penal settlements in Norfolk Island, Port Macquarie and Moreton Bay.” Source: State Library New South Wales, https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/stories/convict-experience

[8] Recently an Australian Review journalist, Laura Tingle, suggested that convicts seemed almost more inclined to die of starvation than to try to feed themselves by farming. She obviously knew nothing of the difficulties experienced by the early settlers, even with the help of convicts, in producing food in this country, well-documented by Watkin Tench, (e.g. Ed Tim Flannery), Watkin Tench, 1788, 2012. Tingle, in Laura Tingle, "Great Expectations" in Quarterly Essay, Issue 46, June 2012, opines that Australian government began by administering a dependent population in a patronising way. Australians became passive recipients of government benefits - to the extent, Tingle believes, that convicts seemed almost more inclined to die of starvation than to try to feed themselves by farming. Moreover, after the gold rush, Australian men got the vote and could run for parliament whether or not they had property and the quality of politicians declined compared to that when only people with property could vote. In these circumstances, politicians with poor manners came to dominate parliament and Australians therefore lost respect for their politicians. See Sheila Newman, “Tingle shoots blanks despite Great Expectations - review of Quarterly Essay,” 8 July 2012, http://candobetter.net/node/3003

[9] An ammendment to the Masters and Servants Act August 1847 forbade the transportation of ‘Natives of any Savage or uncivilized tribe inhabiting any Island or Country in the Pacific Ocean’. Masters and Servants Act 1847 (NSW) No 9a. No.IX., 16 August 1847. Six weeks later a Legislative Council motion disapproved the prospect of introducing Pacific Island workers into the colony, because it “May, if not checked, degenerate into a traffic in slaves.” https://www.themonthly.com.au/issue/2019/july/1561989600/alex-mckinnon/blackbirds-australia-s-hidden-slave-trade-history.

[10] Wilkes, Sue. Regency Spies: Secret Histories of Britain's Rebels & Revolutionaries . Pen and Sword. Kindle Edition. Location 1014.

[11] Theobald Wolfe Tone, The Writings of Theobald Wolfe Tone 1763-98, Volume 3: France, the Rhine, Lough Swilly and death of Tone, Janurary 1797 to November 1798, Eds. T.W. Moody, R.B. McDowell and C.J. Woods, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 2007, p516.

[12] I have mixed with Australian Aborigines from most parts of Australia and can tell you that those I got to know well have expressed strong resentment of mass immigration (black or white), for obvious reasons. Yet, again, the newsmedia conflates mass immigration with multiculturalism and creates the impression that Australian Aborigines have nothing to say against being made an ever smaller part of Australia's demography and land-tenure. This is particularly evident with the Australian ABC. It was demonstrated in the Q&A ABC program of 9 July 2018 on Immigration which included the Indigenous lawyer, Teela Reid. Unusually, The Guardian actually noticed this: ‘Reed, a Wiradjuri and Wailwan woman, appeared to find the whole discussion baffling. “Don’t get me started, the whole bloody country has immigrated or invaded,” she said. “It’s crazy to sit and watch the conversation unfold.” ’ How confusing to be forced to use the rhetoric of multiculturalism as a counter to discrimination against Aborigines, while aware that all these Anglo and multicultural groups are uninvited invaders, not necessarily colonising, but moving relentlessly, and as if by right, onto once-Aboriginal lands and resources.

A report provided by the US Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs contains lists of weapons provided by the United States to Iraq, many of which - including aircraft - would later be seized by ISIS and probably later deployed in Iraq and Syria. These included an horrendous US-manufactured arsenal of chemical and biological weapons: including anthrax, botulinium, and E.Coli as well as human and bacterial DNA. Grotesquely, the United States, which had provided these weapons, has later accused the Syrian Government of using chemical weapons, and Trump has used this as an excuse to invade Syria.

The quotes below are taken from

The quotes below are taken from

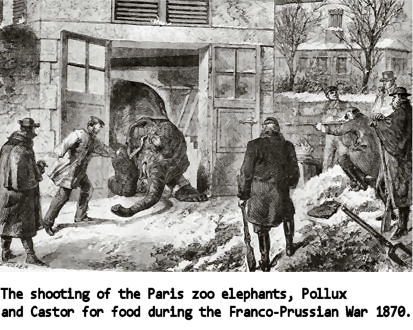

Paul Holden, Ed.'s Indefensible: Seven Myths that Sustain the Global Arms Trade was first published in 2016 by Zed Books,UK, a well-written and well-resourced book that brings us up to date with the trade and also explores its many motives. I don't know if it was overtly stated anywhere in the book, but I formed the impression that excessive arms are collected, bought, and sold by national leaders as a power display and that their buying and selling is a kind of social interplay between globally hypertrophied alpha apes, currying favour or swaggering at each other from the top of their weapons piles and taunting smaller apes. In this anthropological light perhaps we can understand North Korea's leader, Kim Jong-un's resort to nuclear weapons as North America teases him with ostentatious displays of military strength while the world press taunts him as mad. Similarly Gaddafi's purchase of over $30b worth of weapons from world powers was perhaps an unsuccessful attempt to palliate the ferocity of the mad apes in the west.

I was particularly interested to read the history of who sold weapons to the Middle East and was not surprised to find out that it is the same powers that are intervening there to 'stop wars'.

"In the early 1990s, the US Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs released a report confirming that The United States provided the Government of Iraq with ‘dual use’ licensed materials which assisted in the development of Iraqi chemical, biological and missile-system programs, including: chemical warfare agent precursors, chemical warfare agent production facility plans and technical drawings (provided as pesticide production facility plans); chemical warhead filling equipment; biological warfare related materials; missile fabrication equipment; and, missile-system guidance equipment." [1]

"The list of biological material the US provided [to Iraq and which were later stolen by ISIS] was shocking, including anthrax, botulinium, E.Coli as well as human and bacterial DNA.[2] There is credible evidence that when the US invaded Iraq in 1991, US troops were exposed to the very agents that the US had supplied, over and above fighting against the weapons whose acquisition the US had helped to fund and arrange.[2] In the aftermath of the fall of Saddam Hussein, the world was witness to another type of blowback: namely, when an ally is provided arms but fails to stop those arms being stolen by enemies.[3]"

"[...]a 2014 UN Security Council Report noted that in June 2014 alone ISIS seized sufficient Iraqi government stocks from the provinces of Anbar and Salah al-Din to arm and equip more than three Iraqi conventional army divisions.[4] Reviewing the evidence, the same report provided a chilling summary of the range of weapons ISIS has at its disposal:

From social media and other reporting, it is clear that ISIL assets include light weapons, assault rifles, machine guns, heavy weapons, including possible man-portable air defense systems (MANPADS) (SA-7), field and anti-aircraft guns, missiles, rockets, rocket launchers, artillery, aircraft, tanks (including T-55s and T-72s) and vehicles, including high-mobility mobility multipurpose military vehicles." [5]

ISIS took many weapons, almost undoubtedly including chemical weapons, which it probably later deployed in Iraq and Syria, but the United States, which had provided these weapons, later accused the Syrian Government of using chemical weapons, and Trump used this as an excuse to attack Syria militarily.

[1] Source: Holden, Paul. Indefensible (Kindle Locations 978-982). Zed Books. Kindle Edition.

[2] US Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, Second Staff Report on US Chemical and Biological Warfare-Related Dual-Use Exports to Iraq and the Possible Impact on the Health Consequences of the War, 1995. 9Ibid, Chapter 1. 10Ibid, Chapters 2 and 3.

[3] Source: Holden, Paul. Indefensible (Kindle Locations 987-992). Zed Books. Kindle Edition.

[4] The Islamic State and the Levant and the Al-Nusrah Front for the People of Levant: Report and Recommendations Submitted Pursuant to Resolution 2170 (2014), S/2014/815, paragraph 39.

[5] Source: Holden, Paul. Indefensible (Kindle Location 1009-1015). Zed Books. Kindle Edition.

Recording of a timely and important interview with Tony Kevin, author of Return to Moscow UWA 2017. As a young Australian diplomat, Tony Kevin visited Brezhnev's Soviet Union in from 1969-1971. He returned on official business in 1985 when Chernenko was in power, then again, very briefly, in 1990. During these times he was not able to get to know the Russians due to the policy of both governments against fraternisation, thus Russia ironically became a source of growing fascination for him. He continued to inform his fascination from many sources, always at a distance. Concerned today by the threat to peace from US-NATO anti-Russian propaganda, and more fascinated by Russia than ever, he returned on his own to Russia (no longer the Soviet Union, of course) in 2016. Return to Moscow examines past and present attitudes to the people of Russia and to its leaders through empathic eyes and an understanding of the change in geopolitics from cold war to US interventionist.

Recording of a timely and important interview with Tony Kevin, author of Return to Moscow UWA 2017. As a young Australian diplomat, Tony Kevin visited Brezhnev's Soviet Union in from 1969-1971. He returned on official business in 1985 when Chernenko was in power, then again, very briefly, in 1990. During these times he was not able to get to know the Russians due to the policy of both governments against fraternisation, thus Russia ironically became a source of growing fascination for him. He continued to inform his fascination from many sources, always at a distance. Concerned today by the threat to peace from US-NATO anti-Russian propaganda, and more fascinated by Russia than ever, he returned on his own to Russia (no longer the Soviet Union, of course) in 2016. Return to Moscow examines past and present attitudes to the people of Russia and to its leaders through empathic eyes and an understanding of the change in geopolitics from cold war to US interventionist.

On Putin: "Not since Britain's concentrated personal loathing of their great strategic enemy Napoleon in the Napoleonic wars was so much animosity brought to bear on one leader. Propaganda and demeaning language against Putin became more systemic, sustained and near universal in Western foreign policy and media communities than had ever been directed against any Soviet communist leader at the height of the Cold War. This hostile campaign evoked an effective defensive global media strategy by Russia. [...] A new kind of information Cold War took shape, with - paradoxically - Western media voices more and more speaking with one disciplined Soviet-style voice, and Russian counter voices fresher, more diverse and more agile." [Cited from Tony Kevin's book.] The interview in the video took place at Russia House in Fitzroy, Victoria, Australia. It was organised by Claire Woods of the Traveller's Bookstore. The interviewer was Associate Professor Judith Armstrong, former head of European Languages Department at Melbourne University.

An example of the afore-cited disciplined Soviet-style now dictating western newsmedia was to be found in another interview conducted by Australian ABC Victoria's Jon Faine on his Conversation Hour at around 25.25 minutes in: Jon Faine interview: http://mpegmedia.abc.net.au/radio/local_melbourne/audio/201703/abi-2017-03-29.mp3. Faine seems to suggest that Russia is nothing much to worry about because:

JON FAINE: "Russia's found it can't match the west militarily. It can't match the west financially. It can't match the west in industrial design, invention and technology, but it can undo the west through the west's Archilles' heel - democracy."

TONY KEVIN: "No. Russia can match the west militarily. It has a huge nuclear deterrent. We tend to talk among ourselves as though that doesn't exist anymore. It's as if we've all said, 'if we don't talk about nuclear weapons, they won't be there.' But they are there. There are militaries on both sides of the frontier training all the time in how to use tactical weapons. This is the world we live in. And Russia has also gained the great command of this country that used to be clunky and used to be unable to keep up with the west technologically. They're now world leaders in handling information technology, as you know."

Back to the video of the Russia House talk: In response to a question from the audience, Tony Kevin concludes his interview with this statement:

"And I say it here and I say it because of Jon Faine: Syria is one of the points where World War 3 could start. The other two are Ukraine and the Balkan states, on the border of Russia, because, in all these situations, there's a lack of understanding, of comprehension of the other side's point of view. There's a self-righteousness and there's a - I think if Hillary Clinton had been elected president, we would already have war involving the west, Russia, and Syria. That's how bad it is. [...] I know Russia's got a very bad press on Syria, but my position is that Russia is there at the request of a sovereign government, which is run by a man called President Assad, which has a seat in the United Nations, and Russia is trying to help that government hold that country together. And, what are we doing in Syria? We seem to be supporting a change in cast of opposition elements, many of whom we don't really know what their politics are, some of whom are extremely unpleasant people, who do extremely unpleasant things. And, so Syria is a mess. But I'm glad that Russia is trying to help bring about some peace and order in Syria."

Yes, Return to Russia is a very important book, with its author in a position of unique authority, given the perspective of his age and his experience of different epoques in Russia and western deep state international policies. Fortunately it will be hard for the Establishment to completely bury his opinion, so lucidly expressed.

Australian Politics Professor Tim Anderson recently wrote a book entitled, The Dirty war on Syria. In the embedded video, he describes the alarming ignorance of Australians generally about why the West is so down on Syria. This is a fascinating, humane and intelligent interview with Syrian TV. Among the many subjects covered are how the Australian media treats Anderson, how he became interested in the war in Syria, interpreting the propaganda war against Syria, and the future of Syria.

Australian Politics Professor Tim Anderson recently wrote a book entitled, The Dirty war on Syria. In the embedded video, he describes the alarming ignorance of Australians generally about why the West is so down on Syria. This is a fascinating, humane and intelligent interview with Syrian TV. Among the many subjects covered are how the Australian media treats Anderson, how he became interested in the war in Syria, interpreting the propaganda war against Syria, and the future of Syria.

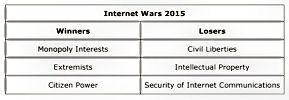

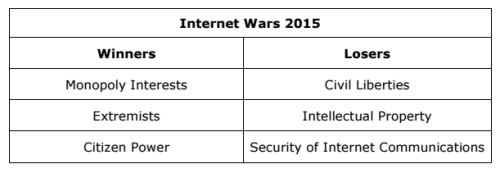

One of the most critical emerging power struggles of the 21st Century is taking place – the battle to control the Internet. The Internet offers up the opportunity for exercising extraordinary political, economic, and military power. Already exploitation of this super-network has helped create the world’s most valuable company, toppled governments, led to the largest wealth transfer in history, and created the most extensive global surveillance system ever So who won the Internet Wars in 2015? E-diplomacy expert and author of the recently released Internet Wars Fergus Hanson has delivered the verdict.

One of the most critical emerging power struggles of the 21st Century is taking place – the battle to control the Internet. The Internet offers up the opportunity for exercising extraordinary political, economic, and military power. Already exploitation of this super-network has helped create the world’s most valuable company, toppled governments, led to the largest wealth transfer in history, and created the most extensive global surveillance system ever So who won the Internet Wars in 2015? E-diplomacy expert and author of the recently released Internet Wars Fergus Hanson has delivered the verdict.

Here are the winners and the losers for 2015 Internet Wars 2015 Winners Losers Monopoly Interests Civil Liberties Extremists Intellectual Property Citizen Power Security of Internet Communications Hanson said 2015 was the year a handful of tech titans consolidated their growing control of key economic chokepoints online, making Monopoly Interests the clear winner in 2015.

Here are the winners and the losers for 2015 Internet Wars 2015 Winners Losers Monopoly Interests Civil Liberties Extremists Intellectual Property Citizen Power Security of Internet Communications Hanson said 2015 was the year a handful of tech titans consolidated their growing control of key economic chokepoints online, making Monopoly Interests the clear winner in 2015.

“In 2013, two tech titans made it into the Fortune 500 top 10 by market “In 2015, there were three in the top five and four in the top 10.

“Apple, the world’s most valuable company, was worth about twice as much as the next two largest companies combined.

“Companies like Apple, Google and Facebook are securing control over key economic chokepoints online.

“This is not to suggest smaller companies will disappear from the Internet, just that to do business, they’ll have to operate through these titans,’ he said.

Hanson said 2015 was also the year extremists ran roughshod over the West “The world’s most powerful militaries, their sophisticated intelligence services and vast financial resources were outmanoeuvred by a relatively tiny number of degenerate fanatics,” said Hanson.

Meanwhile, in the US, the Internet Wars of 2015 have seen the shake up of the Presidential election like never before, shining a light on the aggregating power of the Internet for ordinary citizens.

“Republican voters have flocked in droves to outsider candidates Donald Trump and Ben Carson while, in the Democratic campaign, Hillary Clinton has faced surprisingly strong competition from Bernie Sanders,” said Hanson.

Civil liberties, intellectual property and security of Internet communications are all under siege online, with Hanson declaring them all losers in 2015.

Hanson said the Internet might have extended free speech to many, but in the big picture it has been a double-edged sword.

“Companies like Facebook, with one fifth of the world as users, has begun to exercise an important role as the new moral guardian.

“Its leaked censorship guidelines from 2012 revealed it forbade breastfeeding but gave the thumbs up to crushed heads,” he said.

So is peace possible online?

Hanson said, as a global commons, the Internet will always be open to abuse by individuals, companies, and governments.

“But if broad rules of the road can be agreed, breaches can become the exception rather than the norm, allowing the most important features of the Internet to be preserved.

“This is not an overnight fix. The first step is recognising the turning point we have reached, the critical importance of what’s at stake, and the need to act.

“As an advanced economy and open democracy Australia has a critical interest in securing the Internet’s immense promise into the future.

“Australia should develop a digital foreign policy that identifies our core economic, social and security interests and engage in leading global debates,” he said.

Review of Kenneth Eade's The Involuntary Spy: Who among us realised that Monsanto has huge plans for Ukraine? We learn that Ukraine's current president, Poreschenko, has been in cahoots with the US for years, and that Monsanto has been buying up land and lobbying to change Ukraine's anti-GMO laws, inserting a key clause in an EU Association agreement.

Review of Kenneth Eade's The Involuntary Spy: Who among us realised that Monsanto has huge plans for Ukraine? We learn that Ukraine's current president, Poreschenko, has been in cahoots with the US for years, and that Monsanto has been buying up land and lobbying to change Ukraine's anti-GMO laws, inserting a key clause in an EU Association agreement.

If you wonder what on earth the US is messing around in Ukraine for, this thriller series may actually have some of the inside story.

Kenneth Eade is an international and internet lawyer whose expertise includes the scientific history and laws associated with genetically modified organisms (GMOs). He writes terrific novels around these themes.

Not normally a fan of American spy thrillers, I was, however, intrigued, in light of Edward Snowden, to find that the subject of Eade's spy thriller series, The Involuntary Spy was a US whistleblower who fled to Russia.

Not normally a fan of American spy thrillers, I was, however, intrigued, in light of Edward Snowden, to find that the subject of Eade's spy thriller series, The Involuntary Spy was a US whistleblower who fled to Russia.

Downloading a 'sample' of the book, I was further drawn in by the politics of a car chase through Kiev, as an unsafe place for American whistleblowers in transit to Russia. Hmm, this writer knew a lot about Russia and Ukraine that you don't hear on CNN or read in Murdoch's press. I looked up his biography and discovered that, after practising law for 30 years in the United States, becoming an expert in GMO law, he was disbarred for five years over a disagreement about a Russian goldmine, was married to a Russian woman and lived, apparently more or less in exile, in France. Kenneth Eade's 'faction' novels might have been partly lived as well as derived from real science.

Further reading disclosed that this was an industrial spy novel with a serious ecological and scientific base. Seth, the protagonist, is a genetic biologist attracted to the industry by the ideology of GMOs solving 'world hunger' as well as the prestige and perks of his position. He works for a multinational giant called Germinat, which derives billions from world-wide sales of a pesticide called 'Cleanup Ready' and the promotion of crops it has engineered to be able to survive this ubiquitous and persistant product.

Despite some awareness of French Professor Seralini's (2012-2014) experiments using Monsanto insecticide-resistant GMO sources to feed laboratory rats over a long period of time and how the rats suffered grave consequences which had not happened when they had been fed the actual insecticide, The Reluctant Spy educated me significantly more on the problems with industrial GMOs. I learned that Seralini was not the first scientist to be persecuted for publishing results that put GMOs in a bad light. The author tells us about Arpad Pusztai, who was discredited at first with his 1998 studies (one of the first) on GMO potatoes, showing damage to the gut and immune system.

I knew that Monsanto was extremely powerful and had backed up its patents on genetically modified organisms with legal suits. I did not realise that its position as 'owner' of organisms it has engineered could be used to stop people it did not approve of from testing its scientific claims.[1]

And I learned that, contrary to claims of GMO safe process, organisms used to splice genes have not been limited to the relatively safe unicellular ones; genes from complex organisms with the capacity for multiple and unpredictable outcomes were surrepticiously built into the foundations of today's GMOs.

"It was always thought that bacterial genes were the best form of genes for genetic engineering. Bacterial genes were not as complicated as genes from most plants and animals, because they did not have introns, which could create hundreds or even thousands of different proteins from a single gene, meaning that the gene could not only produce the desired trait, but thousands of others, so there was no chance that the bacterial gene could produce proteins other than the ones it was intended to create. However, when the Bt gene was first introduced into plants, it produced very little Bt protein. So, to pump up production, they added introns because those increased Bt protein production. Instead of testing for whether the introns would also cause the production of other unintended proteins, scientists went with their original assumption that the gene would produce only the Bt protein and nothing else. " Eade, Kenneth (2015-09-15). An Involuntary Spy Series Box Set One: Books one and two (Kindle Locations 857-858). Times Square Publishing. Kindle Edition.)

Seth realises there is a risk that organisms receiving these genes could try to correct what they perceived as a genetic irregularity in themselves and that such an attempted correction could give rise to tumours.

Back at the laboratory, Seth is placed in a position where, like Arpad Pusztai, he is expected to conduct quick and dirty experiments, to back up his employer's dishonest safety claims. His boss, Bill, is 'somewhat of a social climbing stuffed shirt', 'more of an administrator than a scientist' despite 'impressive scientific credentials'. When Seth reports problems, Bill says, irritatingly, "You’re gonna have to do better than shrunken rat’s balls, Seth," and sends him back to the lab.

Typical of the industry, Seth is surrounded by colleagues too fearful of being out of a job to disobey their slickly tyrannical employer, but Seth cannot let go of the truth.

"Genetically modified foods were a grab bag of pesticides, allergens, toxins, dormant viruses and antibiotic resistant molecules that were being consumed by humans for the first time. It was only a matter of time before their immune systems become unable to recognize what to protect against. In this experiment, the entire American public were the test rats and the chemical companies the only winners." Eade, Kenneth (2015-09-15). An Involuntary Spy Series Box Set One: Books one and two (Kindle Locations 1874-1877). Times Square Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Seth discovers more and more apalling things about Germinat, and that people in the United States Government are complicit with its illegal activities. If he goes to the authorities, higher-ups with a stake in Germinat are likely to have him charged as a traitor. He realises his life is in danger. He plans to leave the country. Eventually he has to flee the country. At an unscheduled plane stop in Kiev he narrowly avoids assassination in that state where the elites are so cosy with the US ones.

Half of the book is set in Russia in a seamless and entertaining back and forth. Seth finishes up in a Russian outpost where there is a lot of heavy drinking and promiscuous sex, and he falls in love with a beautiful local. When he tries to negotiate his way back into the United States the author, an international lawyer, gives us some insight into the whistleblower's legal position.

At the end of the first book Kenneth Eade has provided an essay documenting the background to his novel. I cite some highlights here:

[Since 1994] "Genetically engineered foods are in almost all processed food products in the United States. A simple reading of the label will reveal one or more of the following ingredients in every one of them: corn or corn oil, cottonseed oil, canola oil (made from rapeseed oil, a GMO product), soy and/ or soybean oil, and/ or high fructose corn syrup. Genetically engineered corn and soy are used for most of the animal feed in the United States. And GMO sweet corn is now appearing in stores. There are no current federal labeling laws for GMO products, and two labeling measures in California and Washington have been defeated, in the wake of heavy spending of millions of dollars against the measures by Monsanto, Dow Chemical, Bayer, Coca Cola, Kellogg’s, and many others whose name you will see on products on your breakfast, lunch or dinner table. A member of the board of directors of Mc Donalds and one from Sara Lee sit on the board of directors of Monsanto." (Eade, Kenneth (2015-09-15). An Involuntary Spy Series Box Set One: Books one and two (Kindle Locations 786-792). Times Square Publishing. Kindle Edition. ).

In the second book in the series, To Russia for Love, the action takes place in Kiev. It's still about GMOs. Whilst some of you may be aware that Ukraine's location near the Caspian Sea oil reserves and among various oil and gas pipelines thence emanating makes it an object of international interest, who among us realised that Monsanto has huge plans for Ukraine?

We learn that Ukraine's current president, Poreschenko, has been in cahoots with the US for years, and that Monsanto has been buying up land and lobbying to change Ukraine's anti-GMO laws, inserting a key clause in an EU Association agreement. Impoverished Ukraine farmers do not have much defense against financial inducements from Monsanto. Ukraine is the 'bread basket of Europe' with superb soil its main asset, but it is losing control of that last precious resource. And Monsanto benefits from the chaos of US prompted 'regime change' and civil war.

"In late 2013, Victor Yanukovych, the former president of Ukraine, rejected a European Union association agreement tied to a $ 17 billion International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan. Instead, he chose a Russian aid package worth $ 15 billion plus a discount on Russian natural gas. This decision led to his forcible removal from office in February 2014 and the current crisis and devastating civil war. The present government of the Ukraine pursued the IMF loan and a European Union Association Agreement. On July 28, 2014, the Oakland Institute released a report entitled “Walking on the West Side: the World Bank and the IMF in the Ukraine Conflict,” which revealed that the World Bank and the IMF, under the terms of their $ 17 billion loan to Ukraine, would open the country to genetically-modified (GM) crops in agriculture. Because of its rich soil, Ukraine has always been referred to as the “breadbasket of Europe.” According to the Oakland Institute’s report, “Whereas Ukraine does not allow the use of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in agriculture, Article 404 of the EU agreement, which relates to agriculture, includes a clause that has generally gone unnoticed: it indicates, among other things, that both parties will cooperate to extend the use of biotechnologies. There is no doubt that this provision meets the expectations of the agribusiness industry. As observed by Michael Cox, research director at the investment bank Piper Jaffray, ‘Ukraine and, to a wider extent, Eastern Europe, are among the most promising growth markets for farm-equipment giant Deere, as well as seed producers Monsanto and DuPont’. From "Afterword" in Eade, Kenneth (2015-09-15). An Involuntary Spy Series Box Set One: Books one and two, Times Square Publishing. Kindle Edition.