The Business Council of Australia says that the current design of the Government's Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme will force closure of at least three major business, cause four to "fundamentally review their operations", and force others to find ways to cut expenses. It claims to have surveyed 14 businesses over sectors including minerals processing, manufacturing, oil refining, coal mining and sugar milling.

Whilst the problem is real, there is really no avoiding it.

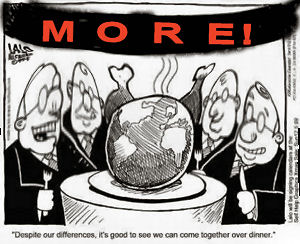

Whilst the problem is real, there is really no avoiding it. The fact is that the kinds of industries and clients that the BCA and similar groups represent cannot expect to survive in their current form. Neither can the tertiary industries that rely on them, such as expensive law firms, frenzied global stock-exchanges, advertising corporations, high-flying consultants and millionaire-salary CEOs.

"Propaganda about a ‘dematerialised economy’ makes it hard to establish the reality that material industrial productivity is not actually less reliant on burning fossil fuels than it was in the 1970s, and that drawdown on fossil fuels has in fact been multiplied by the needs of much greater populations. Similarly the obvious still needs to be pointed out that increasing productivity means burning more fuel and outputting more pollution, accelerating petroleum depletion and adding more greenhouse gases."[1]

We have to face reality. Business and economic structure and expectations have to change.

The Business Council of Australia writes in its recent news release of "The ‘truly dreadful

problem’ of the emissions-intensive, trade-exposed industries." It says, "Professor Ross Garnaut, in his review of emissions trading, accurately describes what he calls the ‘truly dreadful problem’ of EITE industries: so-called ‘carbon leakage’. If we price emissions fully in Australia, emissions-intensive activity might simply relocate overseas. Rather than eliminating emissions, Australia’s regime would move the source of the emissions offshore, most likely to jurisdictions with less stringent environmental standards. Thus a well-intentioned Australian regime could produce the truly perverse effect of actually increasing the level of global emissions."

It is all very well threatening to go overseas, but this will be a very temporary measure; as these industries try to continue to process and sell massive amounts of industrial product, they are going to run into the long-anticipated problem of not having any customers left in the industrialised 'richworld' to sell to, since the people in those 'first world countries', unburdened of corporate accelerated profit-making, will simply slow down and relocalise their activities. Big business will finish up mired in the poverty which it has sought to exploit in its offshore victims.

It adds that, "This problem affects a substantial slice of Australian economic life. The EITE industries contribute 16 per cent of Australian business investment, 51 per cent of exports, 15 per cent of gross value add and employ nearly one in 10 working Australians."

What to do about mass unemployment with the decline of mass production?

Val Yule often says, that it isn't that there isn't any work. It is that the work that needs to be done isn't done because of all the work we do that doesn't need to be done in paid employment which uses up our time and energy.

If we stop working to feed the profit machines, which only expend most of the profits we make for them on more growth, creating more needs for more growth, and less time for everyone, we could, instead, work according to our needs and desires, rather than the hypertrophied needs and desires of a small sector of global power-freaks.

Political commentator and climate activist, Clive Hamilton, writes in Growth Fetish,[1]

Reduction in working hours is the core demand for the transition to post-growth society. Overwork not only propels overconsumption but is the cause of severe social dysfunction, with ramifications for physical and psychological health as well as family and community life. The natural solution to this is the redistribution of work, a process that could benefit both the unemployed and the overworked.

He remarks that

“Moves to limit overwork … directly confront the obsession with growth at all costs,” and talks about the liberation of workers “from the compulsion to earn more than they need.”

Because growth is sustained by a constant ‘barrage of marketing and advertising’ Hamilton wants advertising taxed and removed from the public domain, and television broadcast hours limited so as to

“allow people to cultivate their relationships, especially with children.”

The era of big profits, big business and big government is in terminal decline

The problem is that, with rising fuel costs, the margins for profit are declining. Add this to costs for carbon emissions, and you are looking at a profound challenge for the growthist economy of profit.

We industrialised humans have to change the way we do business and the pace of business.

We are facing global climate change; futures of very unpredictable wind-speeds, temperatures, crop productivity and water availability. We are facing continuous declines in agribusiness productivity because of the decline in availability of fossil fuels. Permaculture will be better able to provide than agribusiness as fossil fuels decline and it will provide better socially as well. See Antony Boy's delightful "Photo essay of a rural Japanese city," for an excellent and entertaining discussion of the problems and solutions.

It is normal for the Business Council and for the Government to be worried, because the necessary changes threaten their systemic hegemony and the whole notion of profit.

If we attempt to go on as we are, Australia faces monolithic power production and government systems, in the effort of the current elite to retain a profit-oriented society, from which the elite themselves are the overwhelming social and financial beneficiaries, at the cost of the greater population. There will be continuous attempts to find finance for huge nuclear power plants to keep up ever less viable industries and giant cities.

The Nuclear route (...) implies total electrification, synthesising, using complex technology, the pattern of settlement and transport which arose from exploitation of the natural endowment of petroleum. It requires massive investment, and in Australia’s case, the investment sought is likely to be private. This implies ongoing loss by citizens of control over the country’s energy systems and all that flows from that – the future of work, the state of the environment, natural amenity. It implies the reshaping of Australian society by corporations with profit alone in mind, for the benefit of a small dominant asset-rich class, with the electorate a mere captive market.[2]

This is a truly unsustainable battle; it will just bring us into feudalism and a much deeper economic depression than a relocalising of all our systems will.

Not only do we not need all the goods we produce for consumption at home or abroad, we do not need the income they bring, and their acquisition is a poor compensation for lives given to industry. Wonderful jobs are few and far between. No-one wants to give those up. Some people also derive much of their social life from work but they would derive similar benefits, and perhaps more status and satisfaction, from other community activities. And plenty of people reach a stage of maturity where childlike obedience to workplace regimes in the cause of producing more and more widgets in different colours, or processing more and more customers a day, with unflinching subservience, challenges every natural instinct.

Instead of those complicated international agreements about percentile reductions in emissions over the years to come, which are hardly enforceable or even measurable, remaining mostly in the control of the corporate emitters, the solution lies much closer at hand, and could ultimately be controlled at grass-roots levels by the masses themselves. Relocalisation is obviously the best way to develop the solidarity and self-sufficiency to reorganize work.

It should be obvious that the slower we work, the more fuel will remain, the less greenhouse gas will be emitted. If the populations which have ballooned to unimaginable proportions since the 1950s were allowed to return (through natural attrition) to more natural sizes by 2050, and the economy permitted to slow, it would take the heat off the planet and us as well. With so much less effort we could make such a positive difference to the planet and to our personal effectiveness.

ENDNOTES

[1] Hamilton, Clive, Growth Fetish, Allen & Unwin, Australia, 2003 and Pluto Press UK, 2005, last chapter, especially, pp.218-220

This article contains extracts from :"101 Views from Hubbert's Peak" in Sheila Newman (Ed.) and from "France and Australia after oil," in Sheila Newman (Ed.) The Final Energy Crisis, Second Edition Pluto Press, UK, 2008 (Available in Australia in late August)

Comments

dave

Mon, 2008-08-25 09:14

Permalink

Externalising costs

Sheila Newman

Mon, 2008-08-25 12:43

Permalink

Tarrifs to protect loyal, sociable Oz industries

Anonymous (not verified)

Fri, 2009-06-19 00:40

Permalink

A poor compensation for lives given to industry

Add comment