Politics of international aid and Syria

Has capitalism, corporatisation and globalisation corrupted big international aid organisations. Is there some way we can boost the grass-roots activists and reinforce whatever is still working within troubled countries like Syria. And what are we doing there, anyway? AMRIS interview inside.

Has capitalism, corporatisation and globalisation corrupted big international aid organisations. Is there some way we can boost the grass-roots activists and reinforce whatever is still working within troubled countries like Syria. And what are we doing there, anyway? AMRIS interview inside.

Vigil for peace, but no forum for discussion

On March 14th 2014 someone convinced me to go to Federation Square to cover the "With Syria" Melbourne Vigil for Peace in Syria. I had thought that this was going to be another politically informative meeting like the 2013 AMRIS forum for peace in Syria, only bigger, involving more groups. It was not until I was on my way that I checked and realised that this was an 'event' rather than a forum and that it was organised by International Aid organisations. But it was too late to turn around.

Highly organised event for spectators

I hoped instead that I would be able to interview any Syrians attending about the worsening situation and the demands by Aid organisations for the UN to get them more penetration into Syria. However, when I arrived, I found that Syrians had stayed away in droves. With the exception of Susan Dirgham (interviewed above) who is the National Co-ordinator for AMRIS, I found no-one there to interview. I did see Bill Shorten, the leader of the Labor Party (currently in opposition in Australia) gliding about in the croud. I thought of going up with my camera and telling him how impressed I was by Anthony Albanese's speech on Syria, and seeing what he had to say, but by the time I had made up my mind, he had appeared and disappeared again like a mirage. In his place, swarms of tee-shirted international aid staff from a variety of organisations buzzed about brightly against the vast grey paved Federation Square, as they set up stalls, red balloons and candles as props for photo opportunities. Officials from international aid organisations spoke repetitively about how Syrians were being turned into refugees, as if no-one there had realised. Why this was happening was not explored. Across Collins Street on the side of the Town Hall was a big electronic announcement saying, "Let's fully welcome the refugees."

Controlling information at the Vigil

I found out that Susan Dirgham had asked organisers at some of the international aid tables for permission to place some of her AMRIS postcards there so that the public could inform themselves about that organisation. She was disappointed to be denied permission to do this. I approached Susan and filmed the interview in the video at the top of this story. Susan told me that the event organisers gave her the reason for her refusal that AMRIS is 'political' with the explanation that International Aid organisations are not. She said she thought that they mean it is 'political' because AMRIS does not support the militarised opposition; it supports efforts for reconciliation in Syria. But, for her, the international aid organisations are political and do support the militarised opposition ('the rebels'). She finds this evident in their failure to condemn the extremist theology of the countries that fund the opposition to the Syrian government and who fight its regular army, supported by outside forces and outside countries, and for not seeing the consequences of this.

For me this was unsurprising, if disappointing, because World Vision, Save the Children, et al, receive financial support from those western external forces that are currently fueling the militarised opposition, and so could hardly be expected to disagree with them and remain in business on the scale at which they operate.

International aid organisations in the global corporate world

Susan noted that people like George Soros and other very very wealthy people fund Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch etc and that these organisations are actually huge corporations in themselves. She added that they have security doors and staff and close their doors to people.

Indeed, they are huge corporations with huge staffs, dependent on vast sums of money to run their affairs and dependent on military forces to give them safe passage into various troubled countries. But they also depend on the mainstream media to publicise their campaigns for finance, so they are not likely to counter the mainstream message. Since most of their funding comes from the West, it is the Western mainstream press they must please.

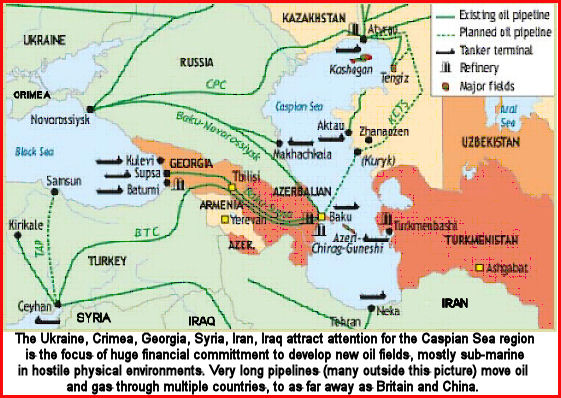

The Anglophone and Western mainstream press, for its part, promotes aggressive pursuit by the US and its allies of geopolitical territory in the Middle East and Eastern Europe, focused on regional oil and gas reserves, notably around the Caspian Sea and outgoing pipelines. International Aid organisations don't talk about this, but then, how could they, when the international mainstream press and the governments supporting war in Syria don't talk about it either.

This geopolitical resource-grabbing is billed as wars against terrorism and for democracy. But democracy in these cases just means capitalism, and foreign investment and take-over of these countries' resources and trading relationships with their neighbours. These wars produce many refugees. Worse, they produce wars in countries which already harbour many refugees from previous wars in other countries. A 2008 survey by ... found that Syria was host to approximately 1,852,300 refugees, with most from Iraq (1,300,000), but many thousands from the former Palestine (543,400) and Somalia (5,200) [1] The refugee influx would have contributed to rapid population growth in Syria, which has swelled from 4.5m in the 1960s to 18m in 2004 and 21.1m in 2011. In October 2013 the UNHCR estimated that 2.1m Syrians had become international refugees, whilst around 7m were displaced, presumably within their own country.

Should the big international aid organisations get out of the area?

Am I suggesting that International Aid organisations should get out of the area entirely? My reading would tell me that those that are incapable of working locally with the Syrian government and by using and shoring up the structures in place, probably should. But what a complex area. The most recent book of many I have read on the question of international aid intervention in disaster was Jonathan M. Katz, The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster, Palgrave McMillan, 2013. Katz made the case that such was the undeserved history of Haiti and foreign intervention that you could not expect an uncorrupted government and that Aid organisations should work with whatever incumbent government and structure exists because if their efforts are independent they undermine the economy, and existing organisational structures.

This is a brilliant book on foreign aid in a disaster among many rivetting books on the subject because of the detailed investigation of the sums raised internationally and where they went. The reporter who wrote it was on the ground there when a major earthquake struck Haiti in 2010 and he stayed several years after. He was present when Clinton and others visited and knew the major Haitian politicians and, most important, both recent and long-term political history. He also spoke the creole language. In his book, he makes several really good points, but the one I want to take up is his criticism of Aid agencies tendency to create their own communications and infrastructure over the top of the government's, thus further undermining all established organisation, however good or bad, and all established business, including local food production.

From this, in addition to my earlier studies, I recognised that it does not matter what you think of a government; any government in a disaster is better than none and you can do a lot to help a country by working through its government, employing nationals and reinforcing and maintaining present infrastructure, institutions and routines.

In Haiti the international aid organisations and foreign dignitaries did not do this and the Haitians got hardly any help. A bunch of foreigners got salaries for going in there and making things worse. That's generally the way of foreign Aid; the money goes on salaries, rent, vehicles, infrastructure, corporate running expenses and public relations. There is not much left over to employ locals with or purchase materials from. Ironically, the big foreign aid organisations are very globalist because they associate with globalist governments and they tend to go along with things like the establishment of cheap garment factories etc. In Haiti, foreign financed factories were planned as part of aid committments where the owners would not pay taxes to the Haitian government. The government was operating with almost no money, yet was held responsible promises not kept by foreign entrepreneurs purporting to be part of the aid effort. This kind of thing destabilised an already fragile government system, but could not replace government. You get the same sorts of people, ex-AID organisation people, sitting on the Committee for Melbourne and dictating to ordinary Australians what kind of infrastructure they should have, who should build it for them, and how fast their populations should grow.

Some questions are asked that raise similar points about a refugee camp in Syria in this article by Kim Wilkinson, "Of Dons and Dust, The Economics of the Zaatari Refugee Camp"

[1] "World Refugee Survey 2008". U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants. 19 June 2008.

How the tragic situation of Haiti's overpopulation and poverty came about? There were not always 9m hungry people there. When this once rich and beautiful island was discovered by Christopher Columbus in 1492, it was inhabited by a population of about 100,000 Amerindians, living in a steady state economy. The Amerindians refused to mine gold for the Spanish, so the Spanish imported many thousands of slaves from Africa. The French took the whole island over in 1697 and it remained their most lucrative possession until 1825, despite the inhabitants claiming independence and freedom from slavery under the French Revolution of 1789. At that time there were few Amerindians but about 400,000 African slaves and 100,000 colonists. Added on 17 Jan 2010. Slavery is ongoing in Haiti.

How the tragic situation of Haiti's overpopulation and poverty came about? There were not always 9m hungry people there. When this once rich and beautiful island was discovered by Christopher Columbus in 1492, it was inhabited by a population of about 100,000 Amerindians, living in a steady state economy. The Amerindians refused to mine gold for the Spanish, so the Spanish imported many thousands of slaves from Africa. The French took the whole island over in 1697 and it remained their most lucrative possession until 1825, despite the inhabitants claiming independence and freedom from slavery under the French Revolution of 1789. At that time there were few Amerindians but about 400,000 African slaves and 100,000 colonists. Added on 17 Jan 2010. Slavery is ongoing in Haiti.

Recent comments