Book Review

A. Peter Klimley, The Secret life of Sharks, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2003.

“There was a massive procession of whales and fish passing by us and moving in the direction of Seamount Espiritu Santo. The first in this animal parade were twenty or so pilot whales. Then came a crescent-shaped formation of dolphin-fish. Then followed a large school of tuna. Were we privileged to be witnessing the slow migration of this whole assemblage toward its next destination, Espiritu Santo? Could this massive assemblage of whales and fishes be using the magnetic lineation on the seafloor below to guide its procession?” Peter Klimley, The Secret Life of Sharks, p.125.

Ichthyologist (fish scientist) Peter Klimley has an ethologist’s eye for communities in the sea. His book describes his own research into shark behaviour, particularly into schooling habits, communication, and navigation methods of particular species. The navigation methods are mind-spinningly different from our own. Klimley concentrates on the navigation skills of schools of hammerhead sharks in the Gulf of Mexico (more below). This focus also leads him to observe ecological communities on the move along the same lines, in the extraordinary procession of whales and fish described above, moving between geological saliences where plant species and therefore fish, aggregate.

Ichthyologist (fish scientist) Peter Klimley has an ethologist’s eye for communities in the sea. His book describes his own research into shark behaviour, particularly into schooling habits, communication, and navigation methods of particular species. The navigation methods are mind-spinningly different from our own. Klimley concentrates on the navigation skills of schools of hammerhead sharks in the Gulf of Mexico (more below). This focus also leads him to observe ecological communities on the move along the same lines, in the extraordinary procession of whales and fish described above, moving between geological saliences where plant species and therefore fish, aggregate.

Repairing the damage from Benchley's Jaws

When I was about 9 years old, my favorite book - long lost - was by Jeannie Lewis, My life as an ichthyologist. This was a rollicking tale of a woman's adventurous career amid the brightly coloured waters of the South Seas. It was illustrated with perky drawings of kinky little animals, like trigger-fish. It also described strange legends of frogs and stones falling from the sky into thatched huts, and revealed some secret women's business.

I wanted to be an ichthyologist because of it, but unfortunately I read Peter Benchley's Jaws Doubleday & Company, NY, 1974, which almost ruined my enjoyment of swimming in the sea. I now see it as a book about developers taking over a town and corrupting its government, but the scene where a huge serrated man-trap silently surges up beneath the slightly drunk swimmer, has imprinted my mind indelibly.

To cope with this after-image of human swimmers as shark cocktails, I have tried to learn more about sharks.

Seeing fish as individuals

What made me buy Peter Klimley's scientifically rich Secret Life of Sharks, as I riffled through its pages in a Brisbane store that markets remaindered books, was noticing how the author made a personal connection with one of the sharks he studied. He had taken Huey, a foot-long baby grey nurse, from the 'Shark Channel' in the Miami Seaquarium, because he felt sorry for him, knowing his certain fate was to be eaten by other sharks in the Channel. The author also has a strong aesthetic sense of nature.

"One day, I couldn't restrain myself from scooping one up in a dip net to keep in an aquarium above my desk at the marine laboratory. The baby shark that I held in my hands was very attractive. It was brown with alternating dark and light bands, each of which merged into the other with a gradual shift in the hue of its color. Speckling his body were small green iridescent spots. Both the bands and spots would gradually disappear as he grew up. Protruding from the forward edge of his nostrils were long barbels. These gave the foot-long nurse shark, whom I named Huey, a comical touch.

Klimley takes the reader on amazing journeys

Klimley is able to take the reader to some amazing places and share with us some unique experiences, such as feeling as if we are also looking up at the sun-silhouetted bodies of sharks above us in the gulf of Mexico. Another strength of this book lies in the author’s skill in relating clearly, but in an interesting and useful way, the details of his experimental work measuring, testing and describing the behaviour of the creatures he swims amongst. We are introduced to a variety of scientific fields and their application in real life. We also get a good picture of the behaviour of the teams of human observers and neighboring fishermen, of the techniques, skills and the risks required to do unusual tasks in unusual environments.

Routine feats of endurance

Feats of endurance were routinely required in much of this marine field-work. These are interesting for the scope they reveal in human performance, especially that of young men, for instance doing repeated free dives to around 100 feet below in order to tag hammerheads. On one occasion, in another situation, the author notices a colleague becoming disoriented and clumsy from fatigue, whilst swimming against a current in choppy waters, and he comments on how unconscious competition between himself and the other swimmer probably contributed to this.

Shark attacks described in accumulated detail

Klimley describes a shark attack on a collegue in the same way he describes shark attacks on seals and other prey. The account is humbling because it is totally unjudgemental, unanthropocentric. (The diver survived.) This doesn’t mean that the author has no feelings for his colleages, for he reveals a strong and appropriate concern in many situations. The difference is that this account falls into a range of accounts from scientific observation of many many feeding behaviours over a period of time off the coast of a remote island where Great White sharks made their living. We are also grateful to learn what turns sharks on and what doesn’t, and the posture they display when they feel challenged.

Klimley outlines his hypotheses and then instructively describes the problems he encounters looking for ways to test these. Any student would benefit from these descriptions. The author shows versatility and breadth in his scientific knowledge, particularly of earth physics.

Stunning findings on undersea animal navigation

Perhaps the most stunning research he describes are his findings on the use of magnetic lineation on the sea-floor to navigate. In this he demonstrates a huge new dimension to life. He shows that some sharks and other sea-creatures have senses which we humans, and most terrestrial animals simply don't suspect exist. He verifies this sensory world through painstakingly devised techniques to measure, repeat, record and locate patterns of behaviour in individuals in hammerhead schools near the Espiritu Santu Seamount in the south western coast of Mexico. He repeats his measurements at night.

"[Salmon] were certainly skilled navigators, but the scalloped hammerheads might be even better: they made nightly migrations far out into the featureless ocean and were able to find the seamount every morning. (…) There was simply no light to guide the shark … Yet she was swimming away from the seamount in a perfectly straight line."

Klimley describes the different forms of magnetization: "The total magnetic field measured at the earth’s surface is the sum of two magnetic sources, the earth’s inner core and its outer crust. Circulation of electrically conductive molten metals in the earth’s core creates the [very strong dipolar magnetic fields of the (…) north and south poles. (…)"

The author explains that magnetic minerals (oxides of iron and titanium) produce smaller dipolar magnetic patterns on the earth, including undersea. Because of the volcanic origin of underwater mountains you often get such dipolar patterns in different locations on the same sea-mount because the north-south poles reversed their polarity between one eruption and the next. This means that the magnetic particles in those eruptions remain aligned according to the prevailing polarity of the north-south poles at the time of eruption.

30 years of diving with sharks tells us another story about ourselves.

People should not be surprised to hear that, as this story of one man's study of sharks is told, over a period of about 30 years, between the early 1970s and the beginning of the 21st century, the numbers of sharks decline markedly.

Sharks are threatened by human predation because it takes them a long time to mature reproductively and they are often taken by fishing well before they reproduce.

Handy tips to avoid the sharp end of sharks

There are many handy tips for those of us concerned to avoid being on a shark's menu.

Here are some humorous ones I have synthesised from Klimley's more sober observations:

Keep your fat to muscle ratio low: To generalize over shark-species, they seem to prefer prey with high fat-content, and will frequently spit humans out because their fat-content compares poorly with preferred prey, such as seals.

Perfect your killer-whale vocalisations: Several shark species have been shown to react with extreme fear to the sound of an orca’s vocalizations.

Wear black and white swimsuits: In some of his early interactions with sharks, Dr Klimley adapted his wetsuit and wore a fin to make himself look like a killer whale (orca) and some species of sharks in certain circumstances made themselves scarce when they saw him. Perhaps this idea might inspire some swimsuit and wet-suit fashion designers.

A. Peter Klimley is an associate professor at the University of Davis, California https://wfcb.ucdavis.edu/www/faculty/Pete

[24reads-to-edit smn]

Apex marine predators choose whom they hang with, researchers reveal. White sharks form communities, researchers have revealed. Although normally solitary predators, white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) gather in large numbers at certain times of year in order to feast on baby seals.

Apex marine predators choose whom they hang with, researchers reveal. White sharks form communities, researchers have revealed. Although normally solitary predators, white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) gather in large numbers at certain times of year in order to feast on baby seals.

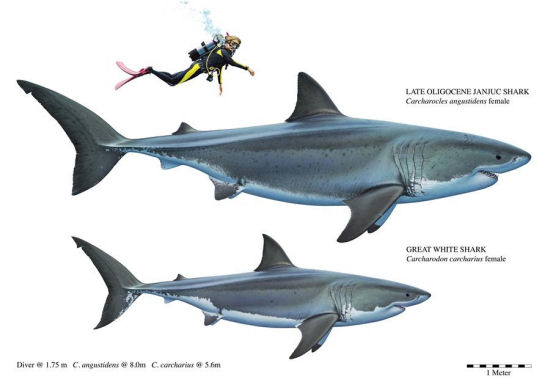

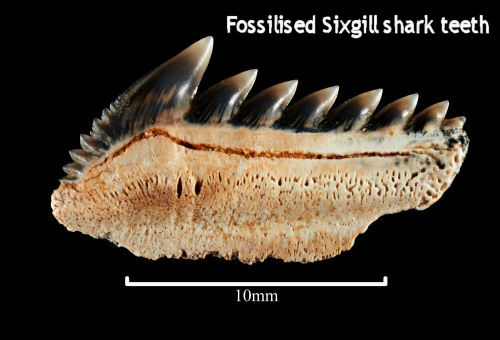

A jaw-full of mega shark teeth – rare evidence that a shark twice the size of a Great White stalked Australia's ancient waters – is to be unveiled at Melbourne Museum on today, Thursday 9 August. Usually shark teeth are found singly, but this time they have the whole set for the gigantic Great Jagged Narrow-Toothed Shark.

A jaw-full of mega shark teeth – rare evidence that a shark twice the size of a Great White stalked Australia's ancient waters – is to be unveiled at Melbourne Museum on today, Thursday 9 August. Usually shark teeth are found singly, but this time they have the whole set for the gigantic Great Jagged Narrow-Toothed Shark.

SYDNEY: Just a week after another fatal shark attack in Australia, University of Sydney PhD candidate and shark policy expert Christopher Neff is leading a world-first project to help reduce the public’s fear of sharks.

SYDNEY: Just a week after another fatal shark attack in Australia, University of Sydney PhD candidate and shark policy expert Christopher Neff is leading a world-first project to help reduce the public’s fear of sharks. The project, entitled ‘Taking the Bite Out of Jaws: An evidence-based look at public fear of sharks’, is part of the Shark Week activities running until Saturday this week at Sea Life Sydney Aquarium.

The project, entitled ‘Taking the Bite Out of Jaws: An evidence-based look at public fear of sharks’, is part of the Shark Week activities running until Saturday this week at Sea Life Sydney Aquarium.

Ichthyologist (fish scientist) Peter Klimley has an ethologist’s eye for communities in the sea. His book describes his own research into shark behaviour, particularly into schooling habits, communication, and navigation methods of particular species. The navigation methods are mind-spinningly different from our own. Klimley concentrates on the navigation skills of schools of hammerhead sharks in the Gulf of Mexico (more below). This focus also leads him to observe ecological communities on the move along the same lines, in the extraordinary procession of whales and fish described above, moving between geological saliences where plant species and therefore fish, aggregate.

Ichthyologist (fish scientist) Peter Klimley has an ethologist’s eye for communities in the sea. His book describes his own research into shark behaviour, particularly into schooling habits, communication, and navigation methods of particular species. The navigation methods are mind-spinningly different from our own. Klimley concentrates on the navigation skills of schools of hammerhead sharks in the Gulf of Mexico (more below). This focus also leads him to observe ecological communities on the move along the same lines, in the extraordinary procession of whales and fish described above, moving between geological saliences where plant species and therefore fish, aggregate.

The final version of Jaws dwarfs all the others. This new monster is eating towns up alive. This is not just a battle to the death; this is WAR! In the novel, Jaws, the monster was not really a white pointer shark, it was the property development lobby, which metastasized with the colonisation of a modest fishing town by rich people from other places. Developers drew power from the wealthy tourists and sea-changers. They took over the original fishing town for their own purposes and democracy seemed fatally wounded. Right to the point of the shark (the developers) trying to eat the boat (symbol of the fishing industry which had begun the town). Until an odd bunch of people had the guts to stand up to the big developers.

The final version of Jaws dwarfs all the others. This new monster is eating towns up alive. This is not just a battle to the death; this is WAR! In the novel, Jaws, the monster was not really a white pointer shark, it was the property development lobby, which metastasized with the colonisation of a modest fishing town by rich people from other places. Developers drew power from the wealthy tourists and sea-changers. They took over the original fishing town for their own purposes and democracy seemed fatally wounded. Right to the point of the shark (the developers) trying to eat the boat (symbol of the fishing industry which had begun the town). Until an odd bunch of people had the guts to stand up to the big developers.

Recent comments