To keep up with global food demand, the UN estimates, six million ha of new farmland will be needed every year. Instead, 12 million ha are lost every year through soil degradation. Australia lost 36 million ha of agricultural land in just the four years from 2005 till 2009. Some of this lost land has occurred because of urban sprawl which is swallowing up some of our best soils close to cities that used to supply the fresh fruit and vegetables. A scathing report by the Royal Commission has gone as far to accuse the Murray-Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) of negligence and being "incapable of acting lawfully," apparently because they overestimated the amount of water returned to the river by a factor of ten. The many warning signs all around us are continually ignored by politicians obsessed with economic theories that defy even the basic laws of mathematics.

To keep up with global food demand, the UN estimates, six million ha of new farmland will be needed every year. Instead, 12 million ha are lost every year through soil degradation. Australia lost 36 million ha of agricultural land in just the four years from 2005 till 2009. Some of this lost land has occurred because of urban sprawl which is swallowing up some of our best soils close to cities that used to supply the fresh fruit and vegetables. A scathing report by the Royal Commission has gone as far to accuse the Murray-Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) of negligence and being "incapable of acting lawfully," apparently because they overestimated the amount of water returned to the river by a factor of ten. The many warning signs all around us are continually ignored by politicians obsessed with economic theories that defy even the basic laws of mathematics.

Australia is mostly a big desert

Australia is the sixth largest country in the world and also the driest inhabited continent on earth, with the least amount of water in rivers, the lowest run-off and the smallest area of permanent wetlands of all the continents.

Its ocean territory is the world's third largest, spanning three oceans and covering around 12 million square kilometers.

One third of the continent produces almost no run-off at all and Australia's rainfall and stream-flow are the most variable in the world.

Soil

Australia also has some of the oldest land surface on earth and, while rich in biodiversity, its soils and seas are among the most nutrient poor and unproductive in the world. This is due mainly to the country's geological stability, which is a major feature of the Australian land mass, and is characterized by, among other things, a lack of significant seismic activity.

Only six per cent of the Australian landmass is arable. As a result, agricultural yields are low compared to other nations: German farms produce over nine metric tonnes/ha compared to Australia's two tonnes.

Australian soils are highly dependent upon vegetation cover and insect biomass to generate nutrients and prevent erosion. It is the native vegetation's long root systems that help break down the sub soil and bring nutrients to the surface, while insects, bacteria, and small animals, reduce ground litter and add nitrogen.

Land clearing, water extraction and poor soil conservation are all causes of a decline in the quality of Australia's soils, now the collapse of insect populations adds another blow. [1]

What causes land-degradation in Australia

The two most significant direct causes of land degradation are the conversion of native vegetation into crop and grazing lands, and unsustainable land-management practices.

Other factors include the effects of climate change and loss of land to urbanization, infrastructure and mining.

However, the underlying driver of all these changes is rising demand from growing populations for food, meat and grains, as well as fibre and energy. This in turn leads to more demand for land and further encroachment into areas with marginal soils.

Market deregulation, which has been a trend since the 1980s, can lead to the destruction of sustainable land management practices in favor of monocultures and can encourage a race to the bottom as far as environmental protection is concerned. The 2016 State of the Environment report noted that:

”Current rates of soil erosion by water across much of Australia now exceed soil formation rates by an order of magnitude or more. As a result, the expected half-life of soils (the time for half the soil to be eroded) in some upland areas used for agriculture has declined to merely decades.”

Our soils are losing their fertility

The carbon content of Australian soils, which is a measure of fertility, is now some five to 10 times lower than when measured in 1845. The UN has warned that there could be as little as 60 harvests remaining before the world's soils in places like Australia reach the limits of agricultural production.

To keep up with global food demand, the UN estimates, six million ha of new farmland will be needed every year. Instead, 12 million ha are lost every year through soil degradation. Australia lost 36 million ha of agricultural land in just the four years from 2005 till 2009. Some of this lost land has occurred because of urban sprawl which is swallowing up some of our best soils close to cities that used to supply the fresh fruit and vegetables.[2]

Despite this, agricultural products accounted for 15 per cent of Australia’s total exports in 2015-16, and the gross value of farm production was more than $63 billion largely because we currently have around two ha of arable land per person, one of the highest rates in the world.

Murray Darling Basin

However 40% of that production came from the Murray Darling irrigation area which had high production based on historic over-allocation of water, something that has now come back to bite us. A scathing report by the Royal Commission has gone as far to accuse the Murray-Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) of negligence and being "incapable of acting lawfully," apparently because they overestimated the amount of water returned to the river by a factor of ten.

Groundwater

With our highly variable surface water supply, groundwater resources are critical for many Australian communities and industries. In some cases, groundwater is the only reliable water supply available to support towns, agriculture and the resources sector. Australia is a very dry country so groundwater is extensively used right across the continent.

Perth relies heavily on the Gnangara Mound aquifer for its water supply, but the water table has been dropping for the past 40 years or more because of reduced rainfall, increased extraction, and decreased recharge.

The Great Artesian Basin, underlying about 1.7 million square kilometres of Australia, contains about 65,000 km3 of water, but it is a “Fossil water”, being up to 2 million years old, so extraction is far faster than replenishment.

It is not widely understood that vegetation and many streams and rivers are supported by the availability of groundwater, either as discharge into streams and rivers or through groundwater uptake by plant roots directly.

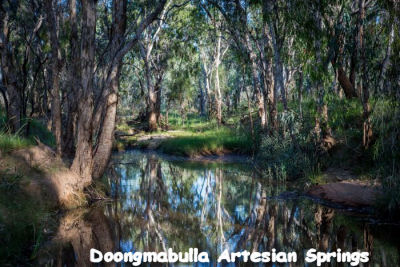

In the Northern Territory, Palm Valley has an average rainfall of only 200mm, but spring fed pools allow its unique flora to survive. The same applies for the Doongmabulla Springs Complex, a one-square-kilometre expanse of nationally important wetlands near the proposed site of the Carmichael coal mine in Queensland, which would probably be destroyed if Adani is allowed to extract the water it needs.

As the pressure in the Great Artesian Basin has declined and the water table drops, mound springs (where groundwater is pushed to the ground surface under pressure) have begun to dry up in South Australia and Queensland.

Associated paperbark swamps and wetlands are also being lost and it gets more and more expensive to extract the groundwater for irrigation and other commercial applications. On average, rates of groundwater extraction across Australia have increased by about 100 per cent between the early 1980s and the early 2000s, reflecting both our increased population size and the associated commercial usage of groundwater stores.

We are also putting these resources at risk from pollution. Already there have been many incidences of ground water being polluted by petroleum products, chemicals, fertilizers, pesticides, salt and even nuclear waste. However the main aquifers are being put at risk from fracking, acid leaching of minerals like uranium and underground coal gasification.

Converting the aquifer’s recharge area into farmland is likely to increase the level of nitrogen compounds while the large blasting used in open cut mining is fracturing rock formations deep underground, allowing contamination of water from above or intermingling with salty water.

Growth economics deaf to reason

All of which explains why scientists have been warning us for years that we cannot continue to grow without doing great damage to our fragile nation, but they are continually ignored by politicians obsessed with economic theories that defy even the basic laws of mathematics.

and......

Underground Coal Gasification was trialed and was proved to have failed in three sites in Queensland with the operator gas company Linc Energy charged with five counts of wilful and unlawful environmental harm. They faced penalties of up to $9 million but were declared bankrupt, leaving the Qld government with a clean up bill of $80m.

Despite this, a similar plant at Leigh creek has been given the green light after a failed challenged by the Adnyamathanha people in the Supreme Court of South Australia. The chairman of Leigh Creek energy claimed that Linc energy was a great company and that there was no environmental damage. Well he would have to say that since he was also chairman of Linc before they went broke.

Add comment