This article, by Dr. Ian Jenkins, was re-published on webofdebt.wordpress.com by Ellen Brown on 11 Sep 2013.

Dr. Ian Jenkins of Arian Cymru (Money Wales) has written two excellent articles on why Wales should have its own bank and how that might be accomplished. The shorter article is reprinted below, and the longer, more technical article is linked here.

Dr. Jenkins is hosting an event in Cardiff on September 26th titled "Banking and Economic Regeneration Wales," at which Marc Armstrong, executive director of the Public Banking Institute, will be speaking, along with Ann Pettifor of the New Economics Foundation and several Welsh leaders. As Dr. Jensen states:

|

This is in an issue on which Wales could provide leadership on an EU-wide level, a matter in which a small nation could make a big difference. |

That is also true for Ireland and Scotland, where interest in public banking is growing. I will be speaking on that subject at a series of seminars in Ireland on October 12th-15th (details here), and I spoke late last year in Scotland on the same subject (see my earlier article here).

Here is Dr. Jenkins' perceptive piece, which applies as well to Ireland and Scotland.

Public Banking for Wales: Escaping the Extractive Model

The economic history of the past 30 years has been, by and large, that of an uncontrolled expansion of the financial sector at the direct expense of the so called 'real' economy' of manufacturing and production. This expansion has been brought about by the hegemony of the free-market doctrines, based principally on fundamentally ideological beliefs in deregulation and privatisation, which have become known as 'neo-Liberal' or 'neo-Classical' economics.

As former US bank regulator William K. Black put it, 'In the world we live in, finance has become the dog instead of the tail [...] They have become a parasite'. The private banks have established themselves in this position through the control of the primary mechanism by which money is created within our system: the issuing of credit. In this paper I will aim to briefly outline how this credit function could be redirected from speculation and bubble creation, which constitute the dominant directions of credit issuance under private banking, towards more stable and sustainable areas which would serve the public interest instead of those of shareholders and bank CEOs. This is not a theoretical method, but rather one which throughout the post-WW II period saw the German Landesbanken facilitate the growth of the mittelstand sector of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs), as well as in the present day constituting the means by which the state-owned Bank of North Dakota (BND) contributes significantly to North Dakota being the only US State to run a budget surplus throughout the post-2008 crisis.

In order for a productive economy to exist there must be adequate streams of affordable credit and it is the absence of such constructive investment which, I would submit, has been a vital contributing factor to the decline of the Welsh economy, and indeed that of the UK, in the past 30 years. Before continuing with this analysis it is worth briefly examining the current banking system and the effect of its operations on the real economy, in Wales as elsewhere.

Banking Now: The Extractive Model of Credit Creation

'What is money and where does it come from?' are, remarkably, questions rarely asked in mainstream economics and even less so by members of the public; yet the answers to these two questions hold one of the keys to understanding the (mal)functioning of our economic system and for devising a new, more democratic direction. As the great American economist G.K. Galbraith observed in his fascinating study of the history of banking Money: Whence It Came, Where It Went, 'The study of money, above all other fields in economics, is the one in which complexity is used to disguise truth or to evade truth, not to reveal it' (Galbraith: 1975, p.1), stating later in the same text that, 'The process by which banks create money is so simple that the mind is repelled' (Galbraith: 1975, p.18). So what is money? The instinctive answer to this question for most people is that money is the physical notes and coins produced by the government; they may even go on to say that this money is produced at the Royal Mint at Llantrisant, ironically making this physical money one of an increasingly diminishing range of Welsh exports. Yet physical money of this sort, in the form of notes and coins, only accounts for approximately 3% of money in circulation. This version of money is indeed the product of government, as under the Bank Charter Act 1844 the power to create banknotes (and coins) became the exclusive preserve of the Bank of England, a power exercised in agreement with Westminster. Since the so-called 'Nixon shock' of 1971 ended the existing Bretton Woods system of international financial exchange by unilaterally cancelling the direct convertibility of the United States dollar to gold the banknotes of the Bank of England/UK government have been essentially what is known as a 'fiat' or 'soft' currency; that is, a monetary unit which is not backed by any 'hard' commodity such as gold and, consequently, is limited in quantity only by the inflationary consequences of overproduction.

So what accounts for the other 97% of money in circulation? To answer this question it is necessary to understand the nature of credit issuance through fractional reserve banking, which is neatly encapsulated by the Statement of Martin Wolf that, 'The essence of the contemporary monetary system is the creation of money, out of nothing, by private banks' often foolish lending' (Wolf: 2010)[i]. This process is profoundly counter-intuitive to most members of the public who would assume that banks lend the deposits they receive, but this is not the case at all: the money issued through the process of creating a loan is created out of nothing, subject only to the rules for capital reserves contained in the Basel Accords. Two publications produced by the Bank of England make the current mechanism of money creation clear:

|

By far the largest role in creating broad money is played by the banking sector [...] When banks make loans they create additional deposits for those that have borrowed the money. (Bank of England: 2007, p.377) |

The second publication, a transcript of speech in 2007 by Paul Tucker the Executive Director (Markets) for the Bank of England and a Member of the Monetary Policy Committee also states that:

|

Subject only but crucially to confidence in their soundness, banks extend credit by simply increasing the borrowing customer's current account [...] That is, banks extend credit by creating money. |

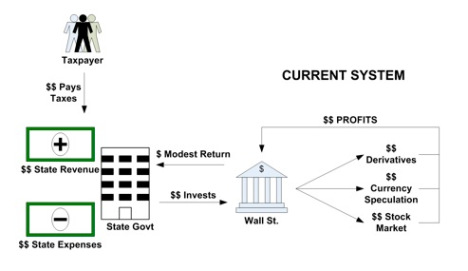

The current system is a product of the fact that the Bank Charter Act 1844 prohibited banks from printing banknotes, but did not prohibit the issuing of money by ledger entry through the making of loans: with the advent of electronic systems in the past thirty years this facility to 'print money' by making entries into borrowers accounts with the stroke of a keypad has expanded significantly. Currently, then, there is a system in place whereby the power of money creation is largely in the hands of private corporations who are able to make sizeable profits through the levying of interest for their performance of this function. This system also leaves the private banks with the decision as to which sectors of the economy should be afforded lines of credit, and in the past thirty years this has moved increasingly away from the productive 'real economy' and towards speculation and bubble creation: with the results we now experience. Part of the deposit base of private banks is the income of local and national government and this leads to a situation wherein private corporations use public money as a deposit base for speculation and lending for speculation (See Fig.1).

The Idea of a State Bank: Re-investment of Interest from Productive Credit Provision

The best current example of a functioning state bank is that of the Bank of North Dakota (BND) in the United States. The way in which the bank functions is best described in its own words:

|

The deposit base of BND is unique. Its primary deposit base is the State of North Dakota. All state funds and funds of state institutions are deposited with Bank of North Dakota, as required by law. Other deposits are accepted from any source, private citizens to the U.S. government. |

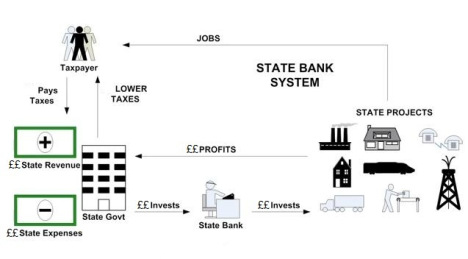

This framework provides the state of North Dakota with what is most needed for a local economy to thrive: affordable (and available) credit for SMEs and resources for the improvement of infrastructure. Under the state banking model the benefit derived from the interest accrued in the credit-issuing process is returned to the state and can be re-invested or spent in accordance with the public interest, instead of being paid to shareholders in dividends or given away in absurd bonuses to bankers who merely carry out a largely mechanical function, however subject to mystification and obfuscation: with myopic incompetence in many cases in the last thirty years (See Fig.2).

In the case of North Dakota this has resulted in the state being the only US state to run a budget surplus throughout the financial crisis post-2008 and this must make their model at least worth considering in a Welsh context.

The Report of the Silk Commission 2012

In Part 1 of its remit The Silk Commission was asked to consider the National Assembly for Wales's current financial powers in relation to taxation and borrowing and its report was produced in November 2012. The commission concluded that the Welsh Assembly government should be granted borrowing powers, basing this conclusion partly on 'international evidence' drawn from a single World Bank publication from 1999: making this 'evidence' neither ideologically neutral, being the product of an organisation which is the éminence grise of global neo-liberalism, nor current, with many of its conclusions being weighed and found wanting by the post-2008 financial crisis. The findings of the commission contains no consideration whatsoever of the role of banks in money creation through credit issuance, and the attendant problems of misallocation of investment, and no investigation of the success of public banking in the international context, for instance in the BRIC economies, or of the potential role of public banking in Wales. For this reason I feel that it is important that these issues be brought into the debate on the Welsh economy, as to ignore it would be to exclude a potentially democratising and sustainable banking system from the national conversation and would merely make any granting of borrowing powers to the Welsh Assembly Government nothing more than a new stream of income for the private banking system. If all that 'responsibility' means in the fiscal context is for Wales as a political unit to submit itself to the 'discipline' of the bond markets, then this is indeed a very sorry direction in which the politicians of the Welsh Assembly are taking both their current constituents, and those yet to be born.

Conclusion

There is a widely perceived need for change to the economic system today and especially for reform of the way in which banking operates, with the majority of the population feeling, rightly, that there is 'something wrong' with the way in which the economy, and particularly banking, currently functions. I believe that a public bank, properly instituted with all due diligence and care for regulation and democratic supervision, can provide one of the possible directions of sustainable change which is so needed in Wales and beyond. The model suggested by the Welsh Conservatives, as it stands, would be no substitute for a real public bank: a bank which would recoup its profits, gleaned from interest on productive loans to the real economy, for the good of the people of Wales. A true Welsh public bank would be in a position to reinvest its profits in socially beneficial areas like education, infrastructure and the health service, instead of funding bonuses and maximising shareholder dividends for a privileged few in the increasingly rarefied world of finance.

______________________________

Bibliography

Ahmad, J (1999) 'Decentralising borrowing powers' World Bank

Berry, S., Harrison, R., Thomas, R., de Weymarn, I. (2007) 'Interpreting movements in Broad Money', Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2007 Q3, p. 377. Available at http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/quarterlybulletin/qb070302.pdf (628K)

The Bank of North Dakota: http://banknd.nd.gov/about_BND/index.html

Brown, Ellen, Web of Debt (Baton Rouge: Third Millenium Press, 2012); The Public Bank Solution (Baton Rouge: Third Millenium Press, 2013).

Commission on Devolution in Wales (Silk Commission) (2012) 'Empowerment and Responsibility: Financial Powers to Strengthen Wales' (full report at: http://commissionondevolutioninwales.independent.gov.uk/)

Tucker, P. (2008). 'Money and Credit: Banking and the macro-economy', speech given at the monetary policy and markets conference, 13 December 2007, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2008, Q1, pp. 96–106. Available at: http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/speeches/2007/speech331.pdf (not there on 12 Sep 2013)

Welsh Conservatives, A Vision for Welsh Investment (January 2013) Available at: http://yourvoiceintheassembly.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Invest-Wales-FINAL.pdf

[i] Wolf, Martin, 'The Fed is right to turn on the tap', The Financial Times, 9/3/2010

Further Information can be found at:

http://publicbankinginstitute.org/home.htm

http://www.positivemoney.org.uk/

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/

Amid Australia's growing conflict over population numbers and democratic planning, we need ideas based on historical and social research, rather than shallow logistics pushed by technocrats. Familiar with these dynamics, I see the challenge of joining this debate with the depth it needs.

Amid Australia's growing conflict over population numbers and democratic planning, we need ideas based on historical and social research, rather than shallow logistics pushed by technocrats. Familiar with these dynamics, I see the challenge of joining this debate with the depth it needs.

Recent comments