Refugees - Living in a media Matrix

The media’s treatment of the recent tragedy of migrants drowning off the Italian island of Lampedusa was predictable. Whenever a local population—whether it be in Greece, Italy, or elsewhere—is inundated with a flood of refugees, a standard news template is applied.

The media’s treatment of the recent tragedy of migrants drowning off the Italian island of Lampedusa was predictable. Whenever a local population—whether it be in Greece, Italy, or elsewhere—is inundated with a flood of refugees, a standard news template is applied.

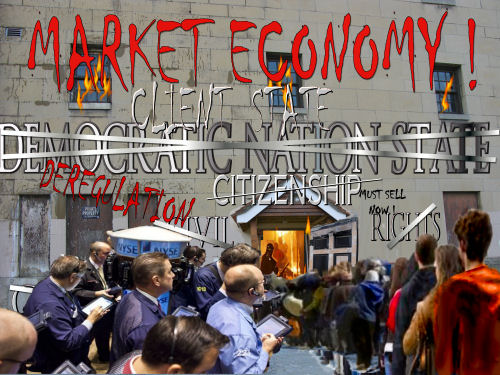

The formula is to convert a broad social calamity into a heart-rending human-interest story that will provoke an emotional response trumping any sober analysis. The intended message is clear. Any number of refugees have an unreserved right to be accommodated by the host society, at whatever the cost.

And the host society and its politicians have an unequivocal moral obligation to meet migrants’ demands, notwithstanding the burdens of preserving a tattered social safety net in the midst of austerity measures and high unemployment in many Mediterranean countries.

And the host society and its politicians have an unequivocal moral obligation to meet migrants’ demands, notwithstanding the burdens of preserving a tattered social safety net in the midst of austerity measures and high unemployment in many Mediterranean countries.

Then we discover that most have fled in the night within a day of being landed on the Italian mainland and being offered six months accommodation, according to Rome Social Services. Many are though to be heading for the more generous benefit cultures in Northern Europe.

The fate of the Lampedusan boat people is tragic, but do the media and politicians seriously think that Europe can take in the populations of Eritrea and sub-Saharan Africa? Where and when will the line be drawn? Do not Europeans—indeed, any people—have the moral right to set limits to their generosity or to husband resources for the primary use of their own citizens?

These are the issues that so many journalists never raise. Apparently the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), the BBC and many others do not acknowledge limits and refugees have rights. That is what we have been told and that is what many of us have come to believe.

Thus it is possible for an indigenous population to see its own displacement as a necessary and vital exercise in humanity, "diversity,” "tolerance,” "pluralism," and democracy rather blatant colonization. In many primary schools in the UK now, virtually 100 per cent of pupils are of foreign origin, where many translators are being hired at public expense to maintain communications in the classroom.

On CBC radio, for example, in a discussion with a French author who expressed concern about growing Islamification of Europe, it was possible for the CBC interviewer to say, without fear of challenge that "we" in Canada are proud of our great diversity of religions and cultures. The multicultural experiment has been a big success. Like the audience, he had lived in the CBC Matrix for so long that he could no longer distinguish between the reality of grassroots concern and the virtual reality that he and others have synthesized over time.

In October and November 2013 the BBC and the UK’s Channel 4 News, did several reports looking at the plight of 'migrant workers looking for a better life' in Athens, southern Italy and Sodertalje - a town south of Stockholm, where the Swedish government's 'remarkable humanity and generous welfare system' has enabled 1000's of immigrants to move in and soon be granted Swedish citizenship.

The Channel 4 news reporter, Matt Frei, noted that they didn't come across any white people while in the town. No mention was made of the views of indigenous Swedes to this social onslaught or whether it was a good policy for Sweden. In the cities of Oslo and Malmo crime rates and attacks on women have gone up significantly. None of this is covered by the international media. The would-be migrants are hardly ever referred to as illegals - always the positive term 'migrant workers', proffering a sense of legitimacy.

Now the Swedish government wants to spread the burden more fairly, pushing other EU countries to take their 'fair share' of this Swedish generosity to would be immigrants. The tone politically and in the media is to unquestioningly accept this continual pressure on the EU, Canada and elsewhere to accept its humanitarian duty, never questioning how this is increasing home grown terrorist threats, food insecurity and infrastructure pressures. It is blatant one-sidedness by a supposedly balanced media.

The migration of Europeans to North America and Australia in the 19th and early 20th century took place in a less crowded world, but large-scale migration now raises vital social, environmental and economic questions about where the world is going and how we deliver reform and a better life for people wherever they are born.

By Tim Murray and Brian McGavin

Recent comments