Little Dorrit: Pensioner Entertainment

Little Dorrit: Pensioner Entertainment

How can we justifiably expect older people to keep working until 70, especially bearing the stresses of physical/manual work? Those without the obligatory hundreds of thousands of dollars in superannuation stored away, likely will be those who are forced to work to 70, and then claim unemployment benefits.

Henry Ergas (The Australian) believes there is a strong case for reforming the age pension. But those changes must be part of a broader restructuring of our retirement incomes system. Unless that?system can provide reasonable income security in old age, the changes will prove neither economically desirable nor politically sustainable.

More Australians are surviving into old age than ever before. But to endorse pension reform is not to echo the doom and gloom about population ageing. It seems to be capitalising on a natural fear of ageing, and of dependency. He says that claims about increases in dependency ratios are wildly exaggerated: while the share of older people in the population is rising, the share of children has fallen, so the ratio of dependence to the working age population is no higher now than at federation.

With longer lives to look forward to, people increase their savings and invest more in education and training, raising productivity. Older people contribute unpaid time to caring for the elderly, the ill and for children. They also provide an army of volunteers for community groups and charities. Longer lives means that retirees and able to spend more money on entertainment, buying consumer goods, and holidays.

Placing income uncertainty is inherently inefficient, and undermines the income predictability that individuals value highly. Raising the eligibility age as longevity increases should provide clear monetary incentives for individuals to continue working by varying the entry level of the pension and its growth rate

It would be politically risky, and unfair, to leave Australians without assurance of incomes is unsustainable, and the public need a retirement system that's fair, efficient and affordable.

What is a dependency ratio?

The total dependency ratio tells us the proportion of the population not in the work-force who are ‘dependent’ on those of working-age, it’s a calculation which groups those aged under 15 with those over 65 years as the ‘dependants’ and classifying those aged 15-64 years as the working-age population.

A study produced by Dr Katherine Betts and published on the Monash University Centre for Population and Urban Research website, says that “if policy makers genuinely want to minimise demographic ageing at the least cost, the most effective way of doing this is to support the two child family and minimise net migration which, in the year ending 30 September 2013, was 241,000.”

Katharine Betts shows that Australia’s labour force participation rate and ratio of dependants to workforce are at record highs, despite an increase in Australia’s median age.

Australia’s average (median) age increased from 28.9 in 1978 to 37.3 in 2013 but, despite this, the proportion of the population aged 15 plus in the labour force has grown. So, high rates of population growth haven't diluted our population's average (median) age.

Data on 31 OECD countries in 2012 show no association between the proportion of the population aged 65 plus and the proportion aged 15 plus in the labour force. These data also show that a number of countries with older populations than Australia’s (such as Switzerland and the Netherlands) have higher labour -force participation rates than ours.

Labour force participation rates among older people are rising and the greater part of government revenue (61 per cent) does not come from taxes on paid labour. So, most of government revenue does not come from paid labour, what's lacking is incoming revenue! The loss of industries, and the slowing of the mining boom, means we've inherited all the “growth” but the economic benefits haven't kept up. Betts says that while the cost of the age pension has grown faster than GDP over the last decade, demographic ageing is not the cause; rising costs have been due to discretionary policy changes.

Data on 31 OECD countries also show that there is no statistically significant association between the proportion of the population aged 65 plus and health-care expenditure as a percentage of GDP.

Demographic Ageing

Demographic ageing is caused by lower fertility (for example a TFR of 2.0, instead of an average family size of 6.5) and longer life expectancy. High net overseas migration (NOM) makes little difference to the median age but a considerable difference to the size of the population, including the size of the population aged 65 and over. An ageing population is an inevitable stage in a community's life cycle. It's a sign that we are heading towards maturity as a nation, and can expect higher living standards, and a sustainable population size.

Productivity Commission

The Productivity Commission report on ageing says that in response to the significant increase in the size of Australian cities, significant investment in transport and other infrastructure is likely to be required. There's no stated aim for this growth!

Betts points out that the infrastructure spending needed to manage population growth over the next 50 years will be five times the total that was needed over the last 50 years. (page 5) Not only this, but illogically, we're doomed to have an even bigger ageing population in the future. Ponzi schemes are self-perpetuating unless there's a deliberate U-turn.

According to the report, Australia’s population is projected to rise to around 38 million by 2060, or around 15million more than the population in 2012

Sydney and Melbourne can be expected to grow by around 3 million each over this period. Australia’s population is projected to increase to more than 38 million by 20 60, more than 15 million above the population in 2012.

.

There's no overall aims or reasons given for this population target, or demographic ambition. The population aged 75 or more years is expected to rise by 4 million from 2012 to 2060, increasing from about 6.4 to 14.4 per cent of the population. So, despite all the immigration that's justified as an effort to keep our population “young”, the proportion of those aged 75 or more will keep rising!

Collectively, it is projected that Australian governments will face additional pressures on their budgets equivalent to a round 6 per cent of national GDP by 2060, principally reflecting the growth of expenditure on health, aged care and the Age Pension.

Australia’s labour and multifactor productivity (MFP) growth has languished in recent years. Without broader policy reforms, it appears that it will be difficult to return to the higher growth rates experienced in the 1990s.

Youth unemployment

At a time when neo-liberals use rising dependency ratios to justify their attacks on budget deficits but then fail to realise that our unemployed youth are a major casualty of the fiscal austerity – that is, our future workforce. (Bill Mitchell)

ABS released a report showing that the number of young people facing long-term unemployment has tripled since the 2008 global depression. The youth ratio dependency ratio is at 28.6% of the population. As such, they are more than half the dependency population because the elderly dependency ratio is 21.5%, with a further 4.2% on support making up the difference.

Australia’s total dependency ratio – defined as the ratio of the non-working population, both children (<20 years old) and the elderly (over 65 years old), to the working age population – is worst under the ABS’ “high growth” scenario, which assumes Australia’s future total fertility rates will reach 2.0 babies per woman by 2026 and then remain constant, life expectancy at birth will continue to increase until 2061 (reaching 92.1 years for males and 93.6 years for females), and NOM will reach 280,000 by 2021 and then remain constant, thereby placing a question mark over claim that high immigration is required to mitigate the impacts of population ageing.

Macrobusiness: Bloxo calls for a bigger Population Ponzi

High rates of welfare unsustainable

Australian families, not specifically the aged, are believed to be receiving more in handouts than they pay in net income tax, new figures reveal.

Modelling for The Daily Telegraph by the National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling at the University of Canberra shows 48 per cent of Australia's 12.2 million "income units" pay no net tax.

The results show as many as 85 per cent of single-parent families pay no tax, once welfare benefits are deducted, while 55 per cent of single-person households pay no tax.

Our ridiculously high rates of population growth, due to “skilled” immigration and family reunion, has outpaced any jobs growth. The “welfare crisis” is a result of lack of government revenues, exacerbated by unemployment, on a landscape of declining industries and productivity.

Monday, 27 April 2015

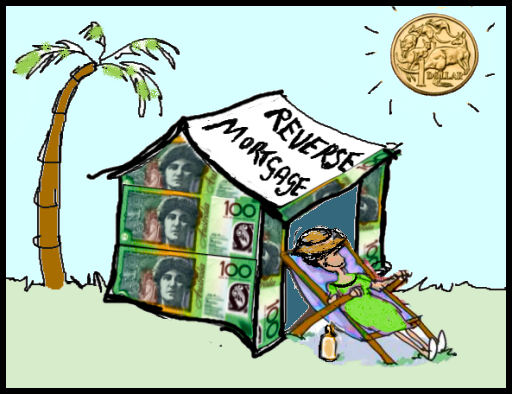

Monday, 27 April 2015  “Government backed reverse mortgages have been investigated in the past for aged care and wholly rejected by Treasury because they effectively make the Federal Government the country’s largest bank.

“Government backed reverse mortgages have been investigated in the past for aged care and wholly rejected by Treasury because they effectively make the Federal Government the country’s largest bank.

Little Dorrit: Pensioner Entertainment

Little Dorrit: Pensioner Entertainment

Recent comments