Why We Need To Talk About Population: Questions and Answers - by Mark Allen

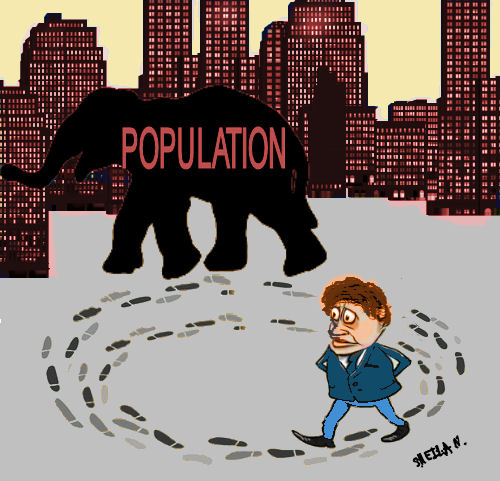

People often ask me why I campaign on population and the reason that I give is that it is an issue that is often overlooked by the environment movement and by the wider world at large. I feel that by ignoring this topic, so much of the other great work done by environmentalists and campaigners is in danger of being severely compromised. Rapid population growth is a worldwide issue and it is also an issue here in Australia. One reason for this is because Australia has one of the highest migration rates in the ‘developed’ world. Due to the way our infrastructure is distributed this is a major reason why an average of 1760 people are added to the population of Melbourne every week and 1600 are added to Sydney. (More by Mark Allen at http://candobetter.net/taxonomy/term/7484)

People often ask me why I campaign on population and the reason that I give is that it is an issue that is often overlooked by the environment movement and by the wider world at large. I feel that by ignoring this topic, so much of the other great work done by environmentalists and campaigners is in danger of being severely compromised. Rapid population growth is a worldwide issue and it is also an issue here in Australia. One reason for this is because Australia has one of the highest migration rates in the ‘developed’ world. Due to the way our infrastructure is distributed this is a major reason why an average of 1760 people are added to the population of Melbourne every week and 1600 are added to Sydney. (More by Mark Allen at http://candobetter.net/taxonomy/term/7484)

As a town planner I cannot ignore the impact that this growth is having in terms of how we can create long-term sustainable communities. This is why I run workshops on suburban sprawl and inappropriate high density and the impact that it has on our changing climate.

With my work I am asked a lot of questions, many on a reoccurring basis, so I thought that I would give my best shot at providing written responses to a number of written questions and comments that I have received over the past twelve months.

Where better to start than the issue of reducing population growth and xenophobia?

Population is not the right factor to focus on. It's a slippery slope to xenophobia and not directly linked to sustainability. It is also very dubious on ethical grounds, no real policy levers, and divisive all around. My suggestion would be to focus on sustainability if that's your objective.

I do understand why people are put off by the topic of population because there are so many people who have hijacked the issue with xenophobic intentions. This is all the more reason why we should embrace the topic with a critical, thinking mindset so that those with narrow minded views can be quickly called out. It is reasoned and rational discussion that will prevent a descent into xenophobia, not ignoring the topic and leaving it in the hands of those who feed off irrational soundbites.

In the meantime, if we continue to ignore the issue here in Australia, we will have to accept that suburban sprawl and unsustainable rates of high density development will continue until the current system breaks. By then we will have greatly reduced our ability to adapt to a low carbon society and we will be left with an environmental and social legacy that may take generations to reverse.

Eventually migrants will want to stop coming here due to the increased commutes and expense as well as services becoming increasingly inaccessible. This is already starting to happen (see The root of Sydney and Melbourne’s housing crisis: we’re building the wrong thing – Bob Birrell The Conversation).

If we wait until migrants stop wanting to come, we will make it so much harder for those migrants who need to come. In short we have to get our planning back into the hands of people who want to build communities.

Population growth has not been sustainable since the Howard era when it was massively increased to increase GDP with deliberately little fanfare. This kind of growth fuels the worst types of development; the type that forces generations of people to live lesser lives, all to justify short term profits. We need to shift our population policy away from growth for the sake of growth model towards one that does what is the most sustainable and the most equitable from a global perspective.

This means using some of the money that would otherwise be spent in trying to reduce the massive infrastructure debt that accompanies rapid population growth to help other countries stabilise their population in a non-coercive way. This money could also be channelled into partnering with them to create permaculture based communities as a way of adapting to and helping to combat climate change.

Secondly, by slowing population growth we can better utilise land that would otherwise be developed to house a rapidly growing population to sequester carbon through regenerative farming practices.

Thirdly, most of our population growth is directed towards the fringes of our cities or in ribbon developments along the coast. As well as being some of our greatest areas of biodiversity, these areas are also have some of our most fertile soils. Therefore slowing population growth in Australia may help us to increase global food security or at the very least reduce our reliance upon importing food from areas of the world who will likely have food security issues of their own.

Lastly, slowing our current rate of population growth will allow us to engage in the slower more considered method of planning that is required to create resilient and meaningful communities that will benefit everyone including incoming refugees and other migrants.

High immigration to Australia doesn't add to net world population so it seems right that Australia should take some of the load.

When you consider that the population of the world is increasing by 80 million a year, the effectiveness of Australia in helping to more evenly distribute global population growth is negligible and it does nothing to stabilise the rate of growth in those regions that are struggling to adapt. It is a reactive approach rather than a proactive one. The fact that Australia’s population centres are situated in some of the most ecologically rich and fertile areas of the continent coupled with the fact that we have a planning system that puts profit before resilience, means that this is having a massive environmental and social impact.

Most of us agree that we need to be reducing our emissions rapidly. Therefore the last thing we need to be doing is compromising our capacity to reduce our food miles by pouring huge amounts of carbon intensive concrete over our inner suburbs and urban fringes. It makes much more sense to reallocate the money that would otherwise be required for all the additional infrastructure into helping people in their own countries adapt to the climate crisis and importantly to partner with them to reduce that crisis. Otherwise we only help a small number of people at a massive environmental and long-term social cost.

We want to be in the best position to provide sustainable resilient communities for those people who cannot stay in their own country for one reason or another. Otherwise incoming refugees will be blown like feathers in the wind into the social isolation of an ever increasing suburban sprawl.

Why not just change the planning system?

We need to work hard to change the planning system and work towards reducing GDP driven population growth. If we do one without the other we will fail because deliberate high population growth is the driver of fast paced suburban sprawl style development as well as prefab concrete apartment developments that are quick to build and quick to age. It is a never ending vicious circle. I saw this with my own eyes when I worked as a planner. Sustainable planning takes time as it is about regenerating wasteland, increasing medium density in the post-war middle suburbs and building new village communities complete with recreation, services and capacity for permaculture. This requires a slower rate of population growth for a slower more considered rate of development.

You seem to be advocating for more development in the middle suburbs. This is where much of our food security could lie and we could end up losing this if we are not careful.

Many of the houses in the middle suburbs are being demolished because they do not meet the perceived needs of 21st century living. Also, because most of them lack heritage appeal, very few people feel the inclination to retrofit them. The middle suburbs (unlike the outer suburbs) are much more connected to public transport and much of the housing stock is within walking distance of public open space. Many of these houses have large backyards. Some of these are well utilised while many are not. So the question is, should we see this 'outdated stock' as an opportunity to encourage increasing the density of these areas (as much of it is likely to be demolished over time) in order to reduce the pressure on the urban fringe? Or should we instead regard these backyards as an underutilised resource which will become all the more relevant as we move towards a low carbon, steady state economy?

Could it be that the larger backyards of the middle suburbs will one day provide the food security that other medium density settlements cannot provide? If so, how much of a willingness is there for the occupants of these areas to become urban farmers? In reality most people see their garden as something that simply needs mowing but resilience is all about the ability of communities to adapt to new social and economic circumstances. In which case those backyards could be seen with a new perspective. I really don't have any firm answers. I believe that we can potentially increase housing diversity in the middle suburbs without threatening their potential as permaculture communities but I know that with the current planning system in place, this will not happen. In reality it will be ad-hoc and many good gardens will be lost and much more besides. Increasing housing diversity in the middle suburbs does make a lot of sense but the potential of these areas to grow food and contribute to local self sustaining economies could be critical in the future. We need to tread very carefully (for more on this issue check out the co-founder of Permaculture, David Holmgren's youtube videos and forthcoming book on retrofitting the suburbs)

Are you not just some privileged white guy trying to protect his way of life?

Anyone who thinks that we should be protecting our way of life is in for a rude awakening sooner rather than later as we are currently living well beyond the planet's capacity to absorb our lifestyle. The only thing that we should be trying to protect is our potential to create sustainable resilient communities that are adaptable to energy descent and that can absorb population growth sustainably. The demographic of the inner suburbs of Melbourne has changed a lot in the past few decades as more and more Greek and Italian migrants are displaced by a white middle class demographic. The irony is that it is this very same demographic that is rejecting a suburban model of living that originated and is still championed by white culture. This will continue under the current paradigm as multicultural areas such as Footscray and Richmond become increasingly gentrified through modern apartment living, all of course under the greenwash banner of urban consolidation*. This forces more communities to be dispersed into the social isolation of the urban fringe. We need to prevent the further gentrification of our existing suburbs while ensuring that new communities are built around a village model, as this is the most socially, ecologically and economically sustainable method of creating communities.

*Urban consolidation (the act of increasing densities within the existing built form as a means of reducing urban sprawl) does not have to be greenwash if:

a) It is not perpetual and ongoing. In other words if the high density is not being constructed to house the endlessly growing population that is needed in order to prop up an over inflated housing market.

b)If a substantial proportion is affordable and within financial reach of those people who would otherwise live on the urban fringe where land is cheaper.

c) A substantial proportion of the units are large enough to be viable for families. This includes being within close proximity to services that are within walking distance, including childcare (most inner suburb areas currently have waiting lists of over a year for childcare services).

d)The apartments are resilient and will last for generations.This includes high quality finishes that will not require constant maintenance and trips to landfill.

e)Apartment developments are incorporated into the fabric of existing neighbourhoods in a way that they do not become the dominant built form and that that their presence is subtle and not detrimental to the overall streetscape. Maintaining the village like feel of our suburbs, including the green spaces within them is essential for long term social and environmental resilience.

Much of the urban consolidation currently taking place in Melbourne fails on all of these points and as result does nothing to reduce urban sprawl whist also compromising much of the existing urban landscape.

You support the Greens policy of increasing our refugee intake but in the future there could be many more refugees as climate change worsens. Where do you draw the line?

Assuming that we do not end up becoming refugees ourselves due to climate change (especially as most Australian cities lie on the coast while the interior is becoming increasingly dry) we could theoretically house an increased number of refugees without increasing sprawl or over developing our existing neighbourhoods. We won't have the economic or environmental justification to build many new towns so the focus will be on retrofitting what we already have and part of this would be retrofitting existing housing stock. In Maroondah alone, at the time of writing there are 3000 empty homes. These are artificial “housing shortages” created by speculators and developers to inflate the value of their investments. Therefore we can provide asylum for people without compromising the ability of our cities to adapt to a low carbon world but of course we have to change the paradigm.

Preserving our capacity to provide food close to and within our cities will however be critical. This is why we need to be focussed on retrofitting what we already have as opposed to creating new development on our precious soils.

New research shows that Melbourne's "food-bowl" supplies 41 per cent of all fresh fruit and vegetables to the city but that is set to plummet to just 18 per cent by 2050 thanks to urban sprawl. It is a similar situation in Sydney.

A major component of reducing our environmental footprint lies in sustainable town planning and that just cannot happen at the current rate of population growth because it is quicker and cheaper to build new estates on the fringe or the unsustainable prefab concrete apartment blocks that we are increasingly seeing in the existing suburbs.

Surely population growth is good because it stimulates change and innovation?

There are some areas of Melbourne that in combination with sound planning and urban design principles could be enriched by a modest increase in population. This however is an issue of poorly distributed growth as opposed to it being an issue of there not being enough growth. Many areas within the wider Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane conurbations are growing much too fast while there are some areas that could benefit from the modest amount of growth that is needed to generate commercial activity (helping to decentralise jobs) while making public transport more economically viable. Therefore we need a slower rate of growth coupled with an improvement on the way that growth is distributed.

We have an ageing population so we must increase our population to compensate.

The drain that older people have on services is over emphasised. Many older people contribute to society well past retirement and if we need to create more jobs to support them, then no problem. It might mean fewer jobs running and maintaining poker machines, a few less real estate agents perhaps, a few less loggers and a few less property developers. And how would we pay for it? The last time I looked there was 452 billion dollars from big corporations and millionaires in Australia that are not being taxed (source: Getup). It is also worth considering that:

1)The average age of a person migrating to Australia is 30. That means they are 30 years older than a newborn baby, which has the affect that in 30 years time the ageing population problem will be even worse than it is now.

2)It is worker-to-dependency ratio that matters, not youth-to-elderly. Australia's un/underemployment is probably over three million people.

3)Demographer Dr Jane O'Sullivan has estimated that it may be costing thirty times more in growing our population to offset ageing than our ageing population is costing.

Migration policy is not the only way of achieving a sustainable population.

Very true. For the answer to this question I will quote Michael Bayliss who is the president of the Victorian/Tasmanian branch of Sustainable Population Australia.

“I envision a future where families with no children are respected as being the societal norm just as much as families with children, and where adoption is seen as a viable and accessible alternative to couples of all sexual and gender identities. The key as always, is through education, empowerment, and allowing people to make their own choices. High schools for example should educate young people into the pros and cons of having children, and with due consideration given to the environmental impacts of having children. I do not advocate fiscal policies that reward large family size, instead this money should be spent on children’s services, such as schools and medical subsidies.”

The questions and answers written above form part of a booklet that is available in electronic format by emailing [email protected]. It is also available as a hard copy from the New International Bookshop in Carlton, Melbourne.

Feel free to contact me at that same email address with your feedback.

Mark Allen is an ex-town planner and environmental activist with a particular interest in population. He runs workshops on Population, Permaculture and Planning across Australia and runs a Facebook group of the same name.

“When discussing population, let your starting point be about finding the issues that you have in common. It could be about congestion, climate change, loss of heritage, the list goes on. It is not about us pushing our view of the world onto people. Instead it is about helping them to see population in a new light by showing how it connects to the issues that are important to them.” This article is based on Mark Allen's speech to the Victorian Branch of Sustainable Population Australia (SPA) Seminar: Attitudes and communication in population and the environment on 23 April 2016. Videos of the event will be available soon.

“When discussing population, let your starting point be about finding the issues that you have in common. It could be about congestion, climate change, loss of heritage, the list goes on. It is not about us pushing our view of the world onto people. Instead it is about helping them to see population in a new light by showing how it connects to the issues that are important to them.” This article is based on Mark Allen's speech to the Victorian Branch of Sustainable Population Australia (SPA) Seminar: Attitudes and communication in population and the environment on 23 April 2016. Videos of the event will be available soon.

Mark Allen from Population Permaculture and Planning locks horns so to speak with West Australian Planning Professor, Professor Newman, over Melbourne's apartment proliferation, in discussion on the Conversation website relating traffic congestion to GDP rather than to population growth, and where the professor has suggested that increasing low cost, low quality, high density appartments would solve housing unaffordability. (If you wish to contribute on The Conversation site, please hit 'newest' on the 'Comments' section to read the latest dialogue at:

Mark Allen from Population Permaculture and Planning locks horns so to speak with West Australian Planning Professor, Professor Newman, over Melbourne's apartment proliferation, in discussion on the Conversation website relating traffic congestion to GDP rather than to population growth, and where the professor has suggested that increasing low cost, low quality, high density appartments would solve housing unaffordability. (If you wish to contribute on The Conversation site, please hit 'newest' on the 'Comments' section to read the latest dialogue at:

Recent comments