Population is a big issue happening in the world today, with our numbers having increased massively from around 1 billion in 1850 to what now looks like 11 billion at the end of the century. Right now, the numbers of the world’s poor increase by 80 million each year and the number of unwanted pregnancies are 210 million per annum. Considering that human population predicts 88% of impact to other animal and plant species (according to the International Union for the Conversation of Nature) human population remains a huge, yet very controversial concern. (This article was written by Michael Bayliss as part of an information booklet with Mark Allen (founder, Population Permaculture and Planning) entitled: 'Why We Need To Talk About Population.' This booklet is designed to engage with a younger, left leaning generation including environmentalists and activists. It will be available at the Sustainable Living Festival Big Weekend at Federation where Mark Allen will also present on town planning and population issues. To find out more, click here.

Population is a big issue happening in the world today, with our numbers having increased massively from around 1 billion in 1850 to what now looks like 11 billion at the end of the century. Right now, the numbers of the world’s poor increase by 80 million each year and the number of unwanted pregnancies are 210 million per annum. Considering that human population predicts 88% of impact to other animal and plant species (according to the International Union for the Conversation of Nature) human population remains a huge, yet very controversial concern. (This article was written by Michael Bayliss as part of an information booklet with Mark Allen (founder, Population Permaculture and Planning) entitled: 'Why We Need To Talk About Population.' This booklet is designed to engage with a younger, left leaning generation including environmentalists and activists. It will be available at the Sustainable Living Festival Big Weekend at Federation where Mark Allen will also present on town planning and population issues. To find out more, click here.

Australia's population numbers

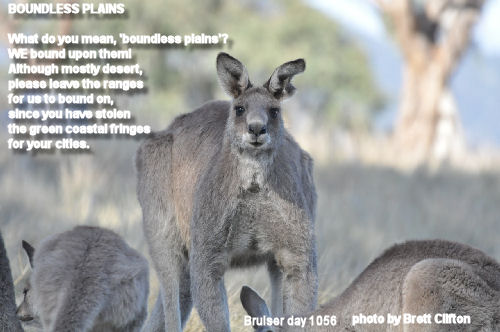

It almost seems absurd to extend these world population concerns to Australia. Australia's a population of just under 24 million (at time of writing) and a density of around 3 people per square kilometre seems minuscule when compared to the demographics of other (mostly densely overpopulated) countries. Surely with miles and miles of free uncharted space, Australia could take its fair share of the world’s load? Isn’t Australia one of the highest per capita fossil fuel guzzling and carbon emitting countries in a society awash with consumerism and materialism? Couldn’t we all consume less, replace those coal industries with renewables, and open up our borders to take in our fair share?

Ecological and logistical considerations

The problem is that when you look at our continent more closely, our vast land of plenty starts to look a bit wanting. Only around 6% of our soil is arable by world standards, with 80% of the land-mass arid or semi-arid. This means that we have an incredibly fragile ecosystem with a very low carrying capacity that has struggled with white occupation for the last 200 years and it is about to get another wallop through climate change. There is every good reason why the south-east coast of Australia is populated and the central and north-west are nearly vacant, and that having large numbers of people live in the interior of Australia makes almost as much sense as populating the Sahara.

Academy of Science opinion on our population

The Australian Academy Of Science has suggested that our capacity to sustain ourselves will be maximised by not exceeding 23 million (whoops, we’ve just done that!) with Jared Diamond and Tim Flannery, painting a bleaker picture - that Australia can only support around 8 million people in the long term for our society’s current level of per capita footprint. This means that to be sustainable, we need to find ways of reducing our per capita and overall consumption by 1/3 at our current population to be sustainable, according to these predictions. However, our population is also growing at a rate of an Adelaide every 3 years, and at this rate our population will double in 35 years time. This will mean reducing our per capita output by 1/6 of current levels in a very short amount of time. What happens after then?...

Breaking taboos

The topic of population has become a taboo in Australia over the past 20 years, partly due to the ongoing perception of us living on an empty continent, and partly due to the mass media promoting the social-demographic arguments of Pauline Hanson, One Nation and others to drown out rational ecologically-based discussion. While there are educated people with no xenophobic agenda currently championing for a sustainable population such as Kelvin Thomson and Dick Smith, there is still confusion in many people's minds between population numbers concerns and racial prejudice. When I ask my friends in the environment movement why they don’t think more about population, the typical reply is: ‘Every time we discuss it, it always ends up with a white guy in his 60s ranting about immigrants.’

Rational discussion

I would like a rational discussion about population to return to the conversations of progressive and socially minded people. Population numbers are intrinsically linked to our economy, and manipulated by our government to fast-track GDP growth (as I shall explain soon) so it is really difficult to talk about the end of neo-liberal capitalism without talking about population numbers at some point. It is hard to talk about cooperative self-resilient communities and eco-villages as the way of the future whilst our town planning system is trying to keep up with an Adelaide’s worth of growth in our major cities every few years. It is hard to share our environment with our native plants and animals for much longer if an end point to our population growth is never debated and if our only option to reduce our per capita footprint infinitely lower is unrealistic. Finally, higher population growth does not automatically mean greater diversity and better outcomes for refugees and asylum seekers. Under our currently societal structure, it can even be the other way around!

Three models and three ideologies

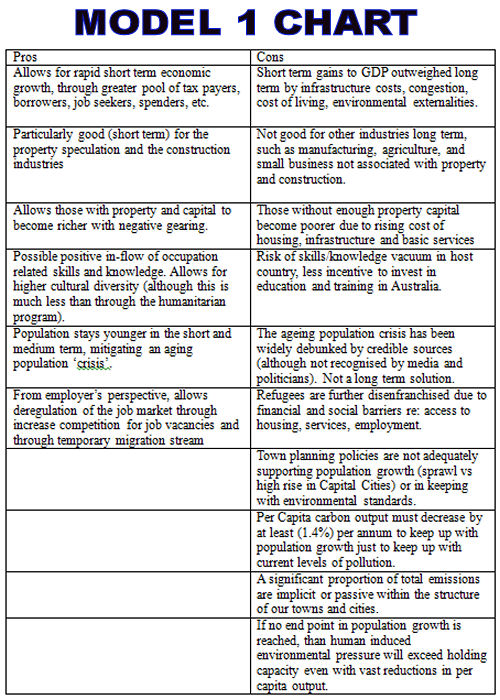

Below are three models of possible population growth in Australia, representing three ideologies, where I want to table the pros and cons with each model. The first is the ‘business as usual’ approach of our current system. The second is an open borders policy, and the third is a sustainable population model.

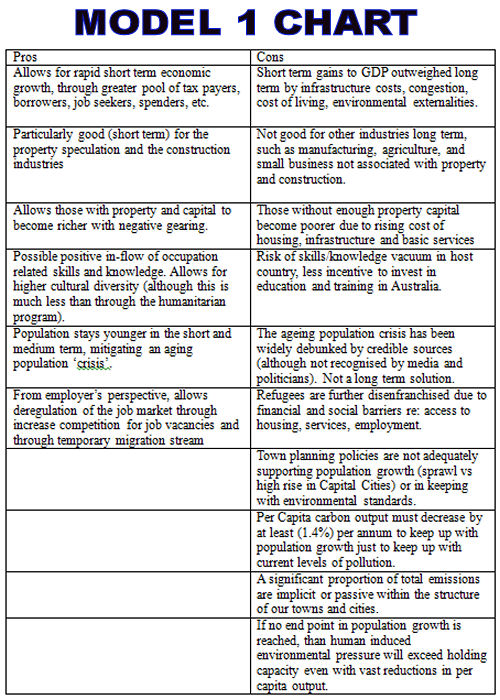

Model 1: Business as usual:

Business as usual with ~1.5% growth per annum, majority of growth policy regulated to raise GDP, and with a current tax system that allows people to pay less tax from owning property (negative gearing).

As can be seen from the chart, our current model of population growth is beneficial for government to raise money through more people paying tax. It is also very beneficial for employers, as it allows an environment for more applicants for jobs, placing downward pressure on wages and conditions. It is most certainly of benefit for those in the property and construction industries, especially for those who invest in property, where a growing customer base ever drives up the demand for the price of properties in established suburbs (for now).

Unfortunately, things become pretty much worse for everyone else. Whilst it is easy enough to deduce the negative effect of this kind of population growth policy has on young job seekers (for example) and in raising general costs of living, it may be surprising to note that refugees, both past and present, are adversely affected by this type of population growth. For example, past generations of migrant market gardeners have been priced out of their area as the urban boundaries of Melbourne and Sydney expand. Likewise, refugee immigrants are being pushed out due to the increased gentrification that comes with high density living in inner city Melbourne suburbs such as Footscray, Carlton, and Richmond that have traditionally been very viable hubs of strong migrant communities. In recent years, new arrivals through the humanitarian program have tended to settle in areas around Broadmeadows, Deer Park, Heidelberg Heights and Dandenong. A far cry from (say) Victoria Street in Richmond, current generations of refugees face social isolation and difficulties in accessing essential services, which makes establishing community or assimilation more difficult. The Multicultural Development Association has reported that refugees in current times are lacking access to essential information, such as what the swimming flags mean on Australian beaches! The fact that Broadmeadows has one of the highest unemployment rates in the country is telling.

Most people are surprised to find out that our humanitarian intake has gone DOWN since the Howard Era, as proportion of our intake, from 25% prior to 1996 down to current levels of around 5-10%. As Howard himself said on 2014 on live radio:

“One of the reasons why it’s so important to maintain that policy is that the more people think our borders are being controlled the more supportive they are in the long term of high levels of immigration. Australia needs a high level of immigration. I’m a high immigration man. I practiced that in government. And one of the ways that you maintain public support for that is to communicate to the Australian people a capacity to control our borders and to decide who and what people and when come to this country.”

In other words, the asylum seeker fiasco during the Howard Government era, Tampa crisis et al, was politically engineered so that people would be complacent to another kind of population growth that the government (and big business) prefers!

Imagine if we traveled to another planet and witnessed and alien society where the government, swayed by big business, had an immigration policy that was based almost entirely on making money for small sectors of society. Imagine this was at the expense of refugees, or people in desperate need from other countries. Imagine the government engineered a border crisis so that refugees were seen as a huge problem so that, once a tough stand seen to be taken towards them, the government used that ruse to bring in population growth policies from other avenues. Imagine, in this society, the the former leader could basically state this word for word and pull the wool over everyone’s eyes. Imagine, in the society where the left were disinclined to call the government out on these policies, for fear of sounding anti-refugee and xenophobic, even when the population policies themselves are discriminatory towards asylum seekers. Imagine if keeping silent perpetuated this growth as a component of the neo-liberalist growth-at-all-costs agenda and if keeping silent on this was a liability on environmental objectives. From an outsider point of view, I’m sure the whole situation would seem more than a little illogical and farcical.

Population has been a very prickly issue for us on the left, particularly in recent decades, with the shadow of Pauline Hanson and One Nation/Reclaim Australia, and particularly when population growth is generally equated in our minds to refugees and open borders policies. However, if we choose to not debate population at all, then our current social and politically engineered population growth policy will continue, the same one that unfairly disfavours refugees and asylum seekers in favour of migration programs that generate short term increases in GDP. This is, to my mind, a very cynical neo-liberalist ideology. We, on the left, have the obligation at the very least to be educated on population policy as it currently stands, and at very least, lobby for a change in policy in favour of the humanitarian program again, even for those of us who are pro-growth. There is also a strong argument that it is very important to support the anti-war movement to prevent the formation of refugees in the first place and that refugee crises are generated by arms manufacture, neo-colonialism and global conflict.

Even if one were recipient to the short-term benefits of this kind of population growth, it must be recognised that the positives are just that - short lived. Eventually, property becomes so expensive that it is not worth investing in anymore. This is called a housing bubble, and has happened to Japan in the late 80s early 90s and currently China and the USA. Coupled with an infrastructure deficit and environmental overshoot, this can only affect everyone in the long term.

So if the current model sounds unfair to most, one might consider a more egalitarian open borders approach. Let’s explore that below, with its associated pros and cons.

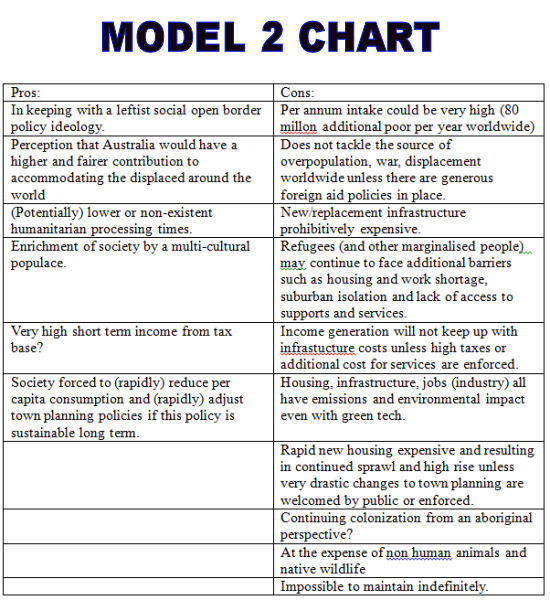

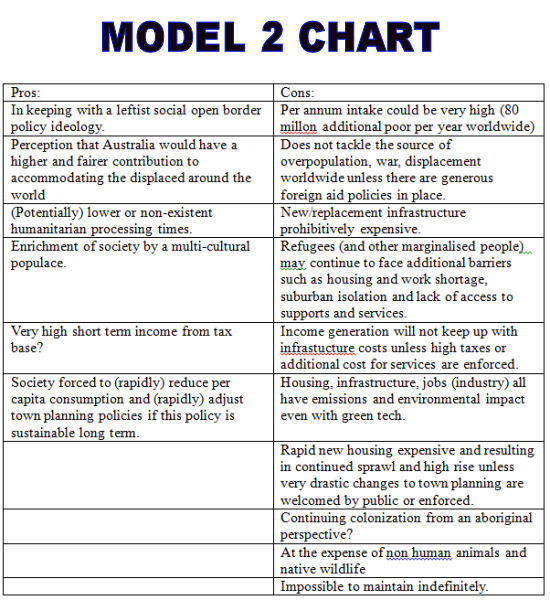

Model 2: Open Borders policy:

Open borders policy, no cap on humanitarian intake, no policy to mitigate natural birth rate or GDP fuelled migration (This is in spirit the policy of the Greens Party). This model assumes growth of 600 000 per annum (250 000 humanitarian, 250 000 GDP, 100 000 natural growth).

This model is conducive to the ideal for many who identify with the social left, as an open border policy provides an unbiased avenue of entry into Australia regardless of race, religion, socio-economic status etc. An opens border policy means that industralised countries such as Australia can play a more definite role in accommodating displaced people from abroad and the idea that everyone is free to move wherever they wish to worldwide. The idea of border restriction or control can be uncomfortable for many as this implies an exclusion from those living in the majority world from the relatively privileged position of Australia. From the political field, many Labor-Left and Greens politicians support this ideology, with perhaps Sarah Hanson-Young of The Greens being the most vocal and well-known advocate of this position.

However, in trying to write the above table objectively, I tried to come up with tangible Pros that were practical rather than ideological. This proved to be more difficult than I was anticipating, and had to put in a few question marks in the pros column as the practical benefits are either tenuous or are a double edged sword with associated cons.

Speaking of the Greens, I’ve observed that many Greens policies cry out for more and more infrastructure (trains, trams, social services, public housing etc). At the same time they generally do not support environmentally destructive mining practices, not least unconventional mining such as fracking. But then, where will all our infrastructure come from? Trains lines, schools, public housing, plumbing - these all require raw materials that need to be dug up from the ground, and processed into tram lines by use of fossil fuels. There really is no way around this unless we learn a way of making train lines out of renewable resources, which isn’t likely. So much of Australia’s per capita consumption is embedded within the town planning system - suburbia and high density apartment living are both inherently resource hungry. Separation of homes and workplaces, and our physical and economic separation from our food sources result in a reliance of our earth’s resources that no amount of wilful reduction of our per capita consumption will mitigate, unless our town planning system changes substantially. If it doesn’t, there is no way we can really put much of a brake on our dependency on resources, and with model 2’s annual growth rate at 600 000 per annum, this could only escalate within our current town planning system. Instead of being able to plan to change the town planning system to accommodate more people in a sustainable way, any government would probably be doomed to play an endless cycle of infrastructure catch up under our current system - at the environment’s expense, even more-so than under our currently system.

I doubt an open borders policy would be practical for any government in the long term. Without an opportunity to transition large scale to a better town planning system, the housing, services and infrastructure costs would be huge. This means either a steep decline in quality of life for residents, or huge taxes or government debt (most likely a combination of all the above). Voters tend to not like those things. Voters on the left would also feel alienated and lied to by a government that would be forced to continue to mine for resources to build the infrastructure with, even if the economy was completely powered by renewable energy. Finally, the huge population growth would have a massive and unavoidable impact to the environment, particularly habitats and water supplies near to the large urban conurbation, even if our per capita footprint were to go down. Any government being elected on an environmental platform would soon let down many of their voters. This is probably a realistic prediction of the Greens if they won government on an open borders platform - they’d soon be shot down. This is also a conundrum that I’m sure many of the left deep down struggle with. That environmental, as well as anti-capitalist objectives, are at odds, at some point, with a human population growth that is not sustainable. Government would survive better, in the long term, if there was some compromise and balance between open borders ideology and the realities of environmental objectives.

Open borders policy only works in the long term if we can work with the world to address the root causes of conflict and displacement that generate high numbers of refugees and asylum seekers. Without this, an open borders policy is great at helping individuals in immediate need for asylum, but can only serve to diffuse the larger problem into the long term. One example is the island of Tuvalu, which made a strong case for evacuating many of its people to Australia and New Zealand in 2003, due to land loss as sea levels rose. New Zealand now has a relocation policy which is very reasonable in those circumstances, however their population is expected to more than double from 12 000 to 28 000 in by 2050. This will mean an endless cycle of relocating people, unless there is a way for Tuvalu to be sustainable in its population growth. Fortunately, according to the UN, non-coercive population sustainability strategies work if women are empowered and educated, and when there is access to family planning and contraceptive strategies (often at odds with the predominating patriarchal religions in host countries). No need for one-child policies or for coercion by the west to the majority world! Mostly grass-roots foreign aid and proactive international cooperation is key.

One final concern with an open borders policy is consideration of the original custodians of our land. My instinct is that any policy to promote population growth without consultation of aboriginal people can be easily argued as more unsolicited colonization of Australia. This belief was certainly shared by some my Noongar identifying friends and community back when I lived in WA, many of whom would be very welcoming to a generous refugee intake, if only their people were consulted on policy. If aboriginal perspective on population issues is hard to find, I imagine this can be attributable to the many other uphill battles that their communities are fighting daily, and poor representation of both aboriginal perspective and the population issue in Australian society. For those willing to search however, there are references in the literature, perhaps most poignantly expressed in the Deaths In Custody Watch Report (1994):

‘Since 1788 the non-Aboriginal powers within our lands have taken upon themselves to increase the population by many millions, meanwhile our population became near to extinction...Australia’s population is bearable at this point in time but further ecocide of this country will leave nothing for no one...Ecologically our land is on its knees: with help it can survive and resuscitate itself, but with any major increase in population this land will die, and we will die with it.’

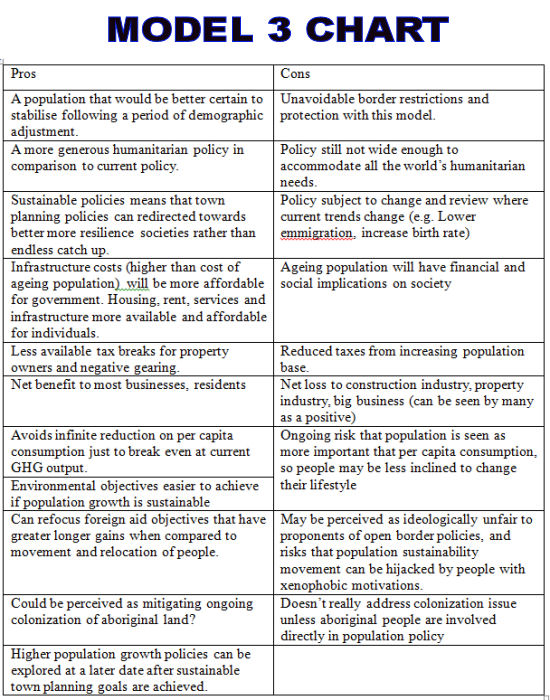

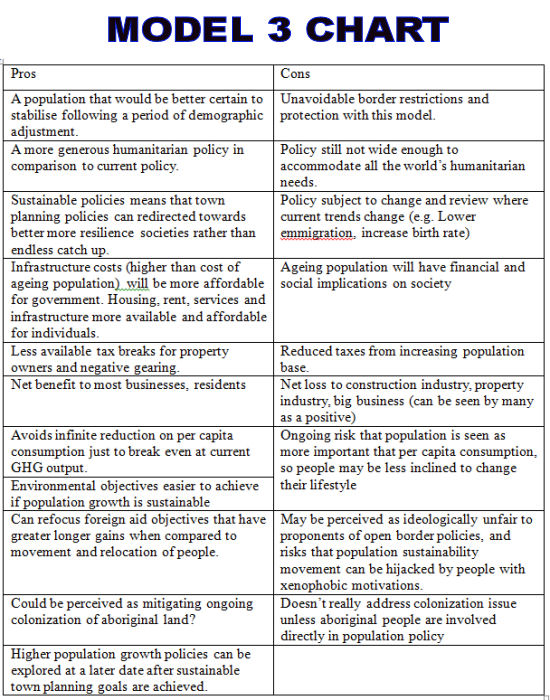

Model 3: Sustainable Population policy:

A medium term sustainable population numbers policy that promotes (1) fiscal policies that do not encourage large family sizes and (2) promotes policies where immigration = emigration (e.g. Between 70 - 80 thousand per annum), with priority given to the humanitarian program (intake of at least 20 000 per annum, with flexibility in times of crisis). An emphasis on foreign aid funding would go to empowering women to make their own life choices, including career decisions, earning capacity and family size.

No model is perfect, and although it is probably self-evident that I advocate for this third model, it would not be objective of me if I did not acknowledge the cons associated with the model. However I would like to highlight that most of the negatives are either risks arising from poor management of the model, or from short term changes as our society goes through adjustments. On balance, this model of population sustainability strikes me as one that allows for the best balance of long term economic objectiveness, environmental and pollution goals, town planning goals, whilst allowing for a defined but generous humanitarian intake. Keep in mind that refugees and asylum seekers would be better off adjusting to a country that had the capacity to provide them with the services that they required to participate fully in their new home. They would not need so much the additional burdens of suburban sprawl, un-affordable housing, and an unforgiving job market that many refugees, along with other disadvantaged groups, face in today’s growth-at-all-cost system. That’s not to say that these problems will disappear, but they will be less and so much easier to address and manage. Currently, many migrants who come to Australia in recent times report feeling very socially isolated in the outer suburbs and miss the greater sense of community that they had back home.

Not that immigration is the only way to a sustainable population - far from it. I envision a future where families with no children are seen as societal norms just as much as families with children, and where adoption is seen as a viable and accessible alternative to couple of all sexual and gender identities. The key, as always is through education, empowerment, and allowing people to make their own choices. High schools, for example, should educate young people into the pros and cons of having children, and with consideration of the environmental impacts of having children, and the implications for future generations with worsening environmental conditions. I do not advocate fiscal policies that reward large family size, instead this money should be spent on children’s services, such as schools and and medical subsidies.

With a sustainable population, more money and energy could go into grass-roots foreign aid instead of more and more infrastructure and more investment could go into transitioning our society and economy into one that less focused on growth and more focused on social and environmental resilience. If our town planning system were to reflect the ideals of eco-villages, intentional communities, and permaculture principles, we would be in a better position to accommodate our current population longer term. We may also be in a better position to assist people in need of asylum or refuge into the future.

Final Words:

I hope this article has helped to disentangle some of the confusion and assumptions that have been barriers for further discussion on population issues for Australia and abroad. Although my own views are currently for population sustainability at this stage, I acknowledge that there will be many differing views and ideas on this topic and I hope my ideas may help to stimulate further thoughtful discussion and debate. I have not yet heard a successful argument for long term high rates of population growth that can also account for positive outcomes for our cities, towns, environment and asylum seekers, however that does not mean that one doesn’t exist! Please let me know if you have any ideas =).

The new Counting Backwards song, Ballad of Yakamia is now out. Yakamia contains the last patch of uncleared bushland in North Albany (Yakamia Forest), West Australia, which is under threat from housing development and road construction. The Council chambers are also located in Yakamia and it is there where decisions about the forest are made.

The new Counting Backwards song, Ballad of Yakamia is now out. Yakamia contains the last patch of uncleared bushland in North Albany (Yakamia Forest), West Australia, which is under threat from housing development and road construction. The Council chambers are also located in Yakamia and it is there where decisions about the forest are made.

The latest film clip by Dr Liz Allen via the ABC explains why we apparently shouldn't be worrying about Australia's population size, because the real issue is in fact social inequality. But what Dr Allen is doing here is creating a false dichotomy. In doing so she is attempting to channel all discussion on what is actually a highly nuanced issue into one where those involved are forced to pick a side.

The latest film clip by Dr Liz Allen via the ABC explains why we apparently shouldn't be worrying about Australia's population size, because the real issue is in fact social inequality. But what Dr Allen is doing here is creating a false dichotomy. In doing so she is attempting to channel all discussion on what is actually a highly nuanced issue into one where those involved are forced to pick a side. I recommend this article by

I recommend this article by  The cartoon by Doug Savage is copyright and comes from www.savagechickens.com.

The cartoon by Doug Savage is copyright and comes from www.savagechickens.com.

'Immigration debate is just left wing racism', according to the headline of Joe Hildebrand's latest article at news.com.au

'Immigration debate is just left wing racism', according to the headline of Joe Hildebrand's latest article at news.com.au  Right now the UK is politically divided on whether or not to leave the European Union and the mood in many quarters is ugly. It seems that there is a very strong chance that the forthcoming Brexit referendum could swing in favour of the Leave vote, something that seemed unimaginable a few years ago. The main reason for most people wanting to leave is because they are concerned with the UK’s rapid rate of population growth. This article is by Michael Bayliss (President of Sustainable Population Australia Victoria and Tasmania Branch) and Mark Allen (Population, Permaculture and Planning)

Right now the UK is politically divided on whether or not to leave the European Union and the mood in many quarters is ugly. It seems that there is a very strong chance that the forthcoming Brexit referendum could swing in favour of the Leave vote, something that seemed unimaginable a few years ago. The main reason for most people wanting to leave is because they are concerned with the UK’s rapid rate of population growth. This article is by Michael Bayliss (President of Sustainable Population Australia Victoria and Tasmania Branch) and Mark Allen (Population, Permaculture and Planning)

People often ask me why I campaign on population and the reason that I give is that it is an issue that is often overlooked by the environment movement and by the wider world at large. I feel that by ignoring this topic, so much of the other great work done by environmentalists and campaigners is in danger of being severely compromised. Rapid population growth is a worldwide issue and it is also an issue here in Australia. One reason for this is because Australia has one of the highest migration rates in the ‘developed’ world. Due to the way our infrastructure is distributed this is a major reason why an average of 1760 people are added to the population of Melbourne every week and 1600 are added to Sydney. (More by Mark Allen at

People often ask me why I campaign on population and the reason that I give is that it is an issue that is often overlooked by the environment movement and by the wider world at large. I feel that by ignoring this topic, so much of the other great work done by environmentalists and campaigners is in danger of being severely compromised. Rapid population growth is a worldwide issue and it is also an issue here in Australia. One reason for this is because Australia has one of the highest migration rates in the ‘developed’ world. Due to the way our infrastructure is distributed this is a major reason why an average of 1760 people are added to the population of Melbourne every week and 1600 are added to Sydney. (More by Mark Allen at

“When discussing population, let your starting point be about finding the issues that you have in common. It could be about congestion, climate change, loss of heritage, the list goes on. It is not about us pushing our view of the world onto people. Instead it is about helping them to see population in a new light by showing how it connects to the issues that are important to them.” This article is based on Mark Allen's speech to the Victorian Branch of Sustainable Population Australia (SPA) Seminar: Attitudes and communication in population and the environment on 23 April 2016. Videos of the event will be available soon.

“When discussing population, let your starting point be about finding the issues that you have in common. It could be about congestion, climate change, loss of heritage, the list goes on. It is not about us pushing our view of the world onto people. Instead it is about helping them to see population in a new light by showing how it connects to the issues that are important to them.” This article is based on Mark Allen's speech to the Victorian Branch of Sustainable Population Australia (SPA) Seminar: Attitudes and communication in population and the environment on 23 April 2016. Videos of the event will be available soon.

Saturday April 23 rd at 1.00pm to 4.00 pm. Venue: Hawthorn Arts Centre, 360 Burwood Rd. Hawthorn Vic 3122. Members and non-members are welcome to attend. Speakers are: Mark Allen, Founder, Population, Permaculture and Planning; Dr Katharine Betts, Population Sociologist, Swinburne University; Hon Kelvin Thomson MP, Environmentalist and high profile sustainable population advocate; Rod Quantock, Environmental activist, Much loved comedian. M.C. SPAVicTas President Michael Bayliss. Audience Q&A and discussion will follow (Free parking behind venue or at nearby Glenferrie Station).

Saturday April 23 rd at 1.00pm to 4.00 pm. Venue: Hawthorn Arts Centre, 360 Burwood Rd. Hawthorn Vic 3122. Members and non-members are welcome to attend. Speakers are: Mark Allen, Founder, Population, Permaculture and Planning; Dr Katharine Betts, Population Sociologist, Swinburne University; Hon Kelvin Thomson MP, Environmentalist and high profile sustainable population advocate; Rod Quantock, Environmental activist, Much loved comedian. M.C. SPAVicTas President Michael Bayliss. Audience Q&A and discussion will follow (Free parking behind venue or at nearby Glenferrie Station).

“So, increasing the population – fast population growth and poor planning – they’re like a vicious circle. When I worked as a planner, I’d go to VCAT and, quite often, development applications would be turned down by councils and the developer’s argument would be, ‘I know, ideally, this isn’t the best place to build this development, but you do know that Melbourne’s population is going to double by 2040-something and so, therefore, we’ve got to start building high-density in areas where we wouldn’t normally build it, because, you know, unless we’re just going to sprawl outwards forever…’. But both are going to happen, so we’ve got to understand that rapid population growth and developers who are making sure that they’re taking control of the planning system - they’re intertwined.” Mark Allen, former planner, of Population, Permaculture and Planning in a speech at the Sustainable Living Festival in Melbourne, 14 February 2016.

“So, increasing the population – fast population growth and poor planning – they’re like a vicious circle. When I worked as a planner, I’d go to VCAT and, quite often, development applications would be turned down by councils and the developer’s argument would be, ‘I know, ideally, this isn’t the best place to build this development, but you do know that Melbourne’s population is going to double by 2040-something and so, therefore, we’ve got to start building high-density in areas where we wouldn’t normally build it, because, you know, unless we’re just going to sprawl outwards forever…’. But both are going to happen, so we’ve got to understand that rapid population growth and developers who are making sure that they’re taking control of the planning system - they’re intertwined.” Mark Allen, former planner, of Population, Permaculture and Planning in a speech at the Sustainable Living Festival in Melbourne, 14 February 2016. Population is a big issue happening in the world today, with our numbers having increased massively from around 1 billion in 1850 to what now looks like 11 billion at the end of the century. Right now, the numbers of the world’s poor increase by 80 million each year and the number of unwanted pregnancies are 210 million per annum. Considering that human population predicts 88% of impact to other animal and plant species (according to the International Union for the Conversation of Nature) human population remains a huge, yet very controversial concern. (This article was written by Michael Bayliss as part of an information booklet with Mark Allen (founder, Population Permaculture and Planning) entitled: 'Why We Need To Talk About Population.' This booklet is designed to engage with a younger, left leaning generation including environmentalists and activists. It will be available at the Sustainable Living Festival Big Weekend at Federation where Mark Allen will also present on town planning and population issues. To

Population is a big issue happening in the world today, with our numbers having increased massively from around 1 billion in 1850 to what now looks like 11 billion at the end of the century. Right now, the numbers of the world’s poor increase by 80 million each year and the number of unwanted pregnancies are 210 million per annum. Considering that human population predicts 88% of impact to other animal and plant species (according to the International Union for the Conversation of Nature) human population remains a huge, yet very controversial concern. (This article was written by Michael Bayliss as part of an information booklet with Mark Allen (founder, Population Permaculture and Planning) entitled: 'Why We Need To Talk About Population.' This booklet is designed to engage with a younger, left leaning generation including environmentalists and activists. It will be available at the Sustainable Living Festival Big Weekend at Federation where Mark Allen will also present on town planning and population issues. To

Sunday 14 Feb 2016 at 12-12.30pm: Mark Allen of

Sunday 14 Feb 2016 at 12-12.30pm: Mark Allen of  Sunday 14 Feb 2016 at 12.30-1pm:

Sunday 14 Feb 2016 at 12.30-1pm:  On Thursday the fifth of November 2015, local, state and federal representatives from The Greens launched their plan for a “Better More Liveable Melbourne” but what impact will this plan have considering Victoria's population is increasing by a hundred thousand a year (especially when most of the growth is in Melbourne)?

On Thursday the fifth of November 2015, local, state and federal representatives from The Greens launched their plan for a “Better More Liveable Melbourne” but what impact will this plan have considering Victoria's population is increasing by a hundred thousand a year (especially when most of the growth is in Melbourne)? At first glance it appears that it would have a major impact, especially as the aim of the plan is to invest heavily in a wide range of projects including three new railway stations, schools in the Docklands, fifty new trams running on 100% renewable energy, a railway line to Doncaster and an upgrade of the train signalling system.

At first glance it appears that it would have a major impact, especially as the aim of the plan is to invest heavily in a wide range of projects including three new railway stations, schools in the Docklands, fifty new trams running on 100% renewable energy, a railway line to Doncaster and an upgrade of the train signalling system.

Mark Allen from Population Permaculture and Planning locks horns so to speak with West Australian Planning Professor, Professor Newman, over Melbourne's apartment proliferation, in discussion on the Conversation website relating traffic congestion to GDP rather than to population growth, and where the professor has suggested that increasing low cost, low quality, high density appartments would solve housing unaffordability. (If you wish to contribute on The Conversation site, please hit 'newest' on the 'Comments' section to read the latest dialogue at:

Mark Allen from Population Permaculture and Planning locks horns so to speak with West Australian Planning Professor, Professor Newman, over Melbourne's apartment proliferation, in discussion on the Conversation website relating traffic congestion to GDP rather than to population growth, and where the professor has suggested that increasing low cost, low quality, high density appartments would solve housing unaffordability. (If you wish to contribute on The Conversation site, please hit 'newest' on the 'Comments' section to read the latest dialogue at:

Recent comments