"Soon all men will be brothers"

We are told that we are in a time of globalisation. Soon all men will be brothers. The Internationale will be the new human race. The sin of Babel is forgiven. The sole language of tomorrow, English, is the chosen one. Already borders no longer protect the bad guys: all the virtuous are united against bin Laden, the butchers of Bosnia are tried in Holland, Interpol hunts burglars. Like Capital, the Proletariat will soon have no country either. The most marvelous thing is that this prodigious work was all done whilst we were sleeping; in the most natural way, apparently; without any special effort.

But then the alarm clock goes off and we open our eyes to a completely different reality.

Walls

Migratory patterns thousands of years old, as vital to human ecology as marine currents are to the life of oceans, have been criminalised. We try to make escape from the human reserves of Africa as difficult and as dangerous as moving from one neighborhood to another in Berlin once was. Sailing northwards, fear of the police, within sight of the Rock of Gibraltar, can pull you to your death. In this street, they have been at war forever with hereditary enemies on the opposite footpath. Europe is, of course, in process of unification, but little Belgium is no longer able to maintain peace between her Flemish and Walloon populations. Sporting matches open with processions of flags and screamed national anthems reminiscent of incitement of hysteria before big military bloodbaths. Indeed, how many peoples have known nothing but war for decades?

So… Are we living in a period dominated by globalisation or by the persistence or even the exacerbation of bellicose sanctification of flags and borders?

The Seven plagues of globalisation

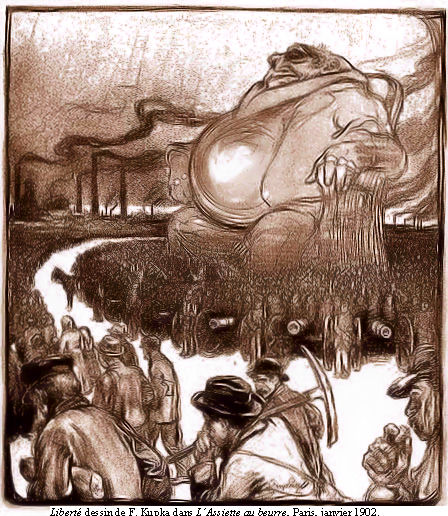

Clearly, we are currently at an early stage of globalisation where only the seven plagues are globalised: globalization of mafias, commerce, financial robbery, man's exploitation of man, subordination of women, ransacking of natural resources and planetary poisoning… Against this background, the economic game is based on the simplest kind of rule: work travels to wherever it costs less. Your wages are not too terrible, you have reasonable social benefits, your government really tries to provide effective public education, health, transport, nature conservation services, DANGER, unemployment awaits! In the countries known as democracies, many people have understood this and have elected governments which are most likely to overturn social progress achieved over a century, and to feign a response to ecological emergencies, without taking the radical measures necessary. The day that British workers return to 19th century conditions, England will once again be the workshop of the world. It’s the law of competition, one of those famous incontrovertible ‘economic laws’.

Utopias

Here and there, however, a few utopians resist this suicidal course.

A utopian is someone who believes that humanity can and must use intelligence to guide his destiny, rather than laws - laws which, since the death of God, are no longer divine - but called ‘natural’ to hide the fact that, in reality, they only exist to protect the interests of the powerful.

Well, as it happens, here are some reflections that globalisation has inspired in one such utopian.

Globalisation is a formidable process which should be intensified.

It is true that competition profits peoples which have the most skillful workers, the most inventive engineers, the rarest minerals, soils and climates specially favourable for particular crops …

But, when the success of a product comes from its low price and that is due to meagre salaries, work done by children or prisoners, at the cost of public health services, education, transport, and to lack of respect towards natural environments, we should say, “We don’t want that money!” and send it back.

We don't want that money

It is relatively easy to work out how much of the cost of a product has been cut through lack of ecological and social policies. Industries which have their products manufactured in places where the costs are smallest, know very well how to do this. They know the value of that “economic and social differential” which causes them to knock on one door rather than another. The price of imported products would then be increased by a sum proportional to that differential, to compensate for the unhealthy basis of their cheapness. No customs taxes, which profit importing countries, would be involved, since the money obtained would be entirely reimbursed to the exporting countries. “We don’t want that money!” It would be up to the exporting countries then, whether they used this money to better the social condition of their population and to preserve their environment, or to add a few diamonds to the crowns of their oligarchies.

According to another – perjorative – meaning, the term ‘utopia’ refers to an absurd, impossible dream. Recent events have shown that nothing could better illustrate that notion of an aberrant utopia than a belief in progress based on the continuing unrestricted freedom of those who have taken all the worlds wealth for themselves.

Francis Ronsin

(Translated by Sheila Newman)

Francis Ronsin was Professor, Department of Contemporary History, at the Université de Bourgogne (Dijon). He has published several books and numerous articles that focus on the relationship between political struggles and private life: La Grève des ventres - Propagande néo-malthusienne et baisse de la natalité en France 19ème-20ème siècles (Aubier, Paris, 1980); Le Contrat sentimental - Débats sur le mariage, l'amour, le divorce, de l'Ancien Régime à la Restauration (Aubier, Paris, 1990) ; Les Divorciaires - Affrontements politiques et conceptions du mariage dans la France du XIXème siècle. (Aubier, Paris, 1992); Le Sexe apprivoisé -Jeanne Humbert et la lutte pour le contrôle des naissances (La Découverte, Paris, 1990) ; and La population de la France de 1789 à nos jours. Données démographiques et affrontements idéologiques (Le Seuil, Paris, 1997); La Guerre et l’oseille (Syllepse, Paris, 2003). He is also the principal organizer of the international research seminar Socialism and Sexuality.

Rights of partial or full reproduction of this article are forbidden without permission from Francis Ronsin.

Add comment