Video and transcript inside

Video and transcript inside This film, made for the conference exposes the lived experience of corrupt, stupid and lethal Victorian forest and fire management, despite and because of the 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission.

The name of the film, "Firebug Economy," comes from Jill Redwood's description of a desperate way of making money out of fires by people in the declining logging business. In the film Jill also talks about the low flammability of old growth forests and the horrible synergy of forest removal, wildlife loss, and global warming, greatly accelerated under Victoria's 'planned burns policy'. Government policy has been stealthily converting old growth forests into plantations. Is the final aim is to sell them for farmland and urban development as Victoria burns?

Please come to the Pause and Review conference in Melbourne 9th Nov 2014 at Kindness House, 288 Brunswick Street, Fitzroy Melbourne. Starts 10am. Contact: Maryland Wilson 0417 148 501. Jill Redwood of Environment East Gippsland is famous for leading the first ever successful case by an environmental organisation against a government logging firm. In this film we find that the trees granted protection in the famous EEG court case against VicForests have since been vengefully felled.

Speakers include:

Speakers include:

Philip Ingamells Victorian National Parks Association

Speaker Bob Mc Donald Naturalist

Joel Wright - Indigenous speaker on traditional Aboriginal fire management.

Michelle Thomas - well-known wildlife rescuer and carer from Animalia shelter

Maryland Wilson (President of AWPC) will lead a discussion and Action Plan from 3-4pm

How does forest-logging increase fire-risk and climate change?

Jill Redwood: Well, we've always thought this, but a study that's just come out from the ANU and Melbourne Uni [Lindenmayer, McCarthy, Taylor, "Non-linear effects of stand age on fire severity," see also "Code of destruction Lindenmayer deplores Victoria's future forest policy][1] shows that where the logging regrowth grows back after total clearfell (which is the only method used around here, even though they might give it a different name of 'seed tree', is pretty well clearfell back to bare-earth burn. And then what comes up is like ... It's converted to a pulpwood farm, basically. You don't get your forest back. What you get back is a tree-crop, and it's perfectly suited for the woodchip industry because they like the nice young white straight uniform predictable trees.

So, where we used to have age-diversity, species diversity, ferns - you know, the different stratas in the forest - you just get the one species coming back, thick as hairs on a cat's back.

As well as very thick regrowth, that's very thick and very flammable, they compete with each other for light, nutrient and water, so you also get a lot of them die off, which are then - it's just like creating a tinderbox. One, of the dead wood to carry the fire and to burn really well, and then, all this young, oil-filled eucalypt foliage. And it's just like a funeral pyre - especially when it's around towns and communities. It really goes up like a bomb. Whereas you get your natural forest and you get your different strata in the forest. You get your canopy from the old growth - really high - very hard for that to carry a crown fire, as in the young forests that carry crown fires. You get the mid-story, you get the tree-fern understory that creates this microclimate, where there's always dampness, there's moss on logs - and it's just very fire-proof. Natural forest is fire-proof and there are a lot of lightening strikes actually hitting those areas and they never go anywhere. But you get a lightening strike on a ridge-top, or a regrowth forest, and it just goes like a bomb! The whole landscape, the hillside, wherever they log, it's drying it out and creating a different forest that's far more flammable.

The government's 'planned burns' policy

[Following the 2009 Victorian bushfires, an inquiry came up with a policy for mandatory burning of 5% of Victoria's forests per annum - that's 100% in 20 years. See under "Land and fuel management", http://www.royalcommission.vic.gov.au/Assets/VBRC-Final-Report-Recommendations.pdf Recommendation 56: "The State fund and commit to implementing a long-term program of prescribed burning based on an annual rolling target of 5 per cent minimum of public land"]

The way I see what's happening with the government planned burns is it gives the community a false sense of security. They have to do something to look after people from big bad fires. It's actually climate change that's creating it, and the logging. Both of those together are a deadly combination.

Sheila Newman, Interviewer: According to some theories the logging is creating the climate change, certainly in the hinterlands. [Text insert reference in film after the interview to Gorshkov and Makarieva's Biotic Pump theory].

Jill RedwoodIt's a feedback loop that's just not going to end unless the government does something to say, 'Right, this is enough. Let's try to get it back to what it was. '

But what they're doing, as a 'solution', is saying, 'we need to burn to stop the burning'. What they're doing is taking out the natural fire-proofing of a forest. And that is all the little hoppers and scratchers and diggers, like the potoroos, the bandicoots, that turn over leaf litter. Lyrebirds. They can cover - turn over - about two and a half tons a year. Each lyrebird. So they're constantly making this compost out of the leaf-litter and twigs on the forest floor. The mosses, the funghi, the termites - all the insects! The moth-larvae that are actually evolved to eat dry gum leaves - not much else is. These are the things that, when they put a fire through, and say, 'Alright, we're safe now, it's all burnt!' They are destroying the very thing that can fire-proof a forest that's been working for millions of years.

[Leaf litter shown in film. It holds a lot of water, as well as nutrients and funghi, so is not flammable, but, as Jill quips, 'It's not flammable, but it's what the public are taught to fear'. If we leave the little animals in there, they will get rid of it; they'll turn it over and digest it and the funghi will eat through it. ]

So they're killing of the little animals, they're exposing them to predation by foxes. They're taking that layer out that shades the forest floor, that keeps the damp ness going. And, if anybody's ever made compost, they know you've got to keep moisture in it and you've got to have your little creepies and bacteria and everything working together to break down that leaf-litter and the twigs. And that's why the old growth forests won't burn. And up here, during the 2014 fires, we saw it roar through a lot of fairly dry open forest that's been logged. Soon as it hit Brown Mountain, it went out. They tried to burn it with - DEPI would try to burn [dog interrupts, barking] ... DEPI being the Department of Enviroment and Primary Industry. And, what they were doing is, not just - they weren't fighting the fire - they were just lighting more fire - and that's a whole other story. The way they managed these fires in [summer].

Sheila Newman, Interviewer: And their intention was to light a fire they could manage, which would mean that, by the time the wildfire got to it, it would run out of fuel? That's their theory?

Overtime and bonuses created through burning off

Jill Redwood: It also created a lot of reall good overtime and bonuses. But... anyway...

Sheila Newman, Interviewer:Well, that's a valid thing to comment on.

Jill Redwood: Oh God, it is!

Sheila Newman, Interviewer:Because it's not like ....

Jill Redwood: And we dare not because, oh my God, you're questioning these brave fire-fighters? Well, I didn't see any fire-fighters actually front a fire with some water. They were just lighting fires, all the time, so the boundary was getting bigger and bigger. And that... You know, the bushfire, probably would have been 'this big' but the way DEPI were managing it, the government fire-fighters, they just kept lighting fires to try and burn back into it, and then they'd escape and jump [indicates fire jumping over boundary] and they'd have to bulldoze and light another fire. And I'm sure about half the size of this fire was due to government initiated bushfires, in the hottest period, in the dry summer.

We had the big one up in Deddick. They didn't jump on that. That was one they could have jumped on immediately. That's the one that got out of control. And they were sort of waiting for it to come out, which, in the mean time it got bigger and bigger, until February the 9th, when it was so big they couldn't do anything about it and it just sort of took out half of Tubbit, Bonang, Goongarah... We were surrounded by fires and that February the 9th, it just burned out the top end of Goongarah and took out so much forest. It just - it was so intense, there wasn't a green thing, a living thing left after it went through. And this is just for miles and miles. To that extent. Somebody said, that they could have got in there, the rappelle crews could have got in, there was actually a way to get in there with four wheel drives. They could have done something about that, but they didn't!

Cienwen Hickey (local wildlife activist): They don't use a strike team anymore, do they, as they used to.

Jill Redwood: No. It's all too dangerous, but - so they just wait for it to come out and make the fires bigger and bigger and bigger. And we, our volunteer fire-brigade here, had to go out at night and put out fires that DEPI had lit the night before, and went back home. You know, they've got bank hours, like nine to five.

Cienwen Hickey (local wildlife activist): Well, they knock off at five o'clock.

Jill Redwood: They're not patrolling at night. They're not doing work on fires at night when they could, when it's cooler, when it's damp and the air's got moisture in it...

Sheila Newman, Interviewer: Is this in the middle of a bushfire they go home at night?

Jill Redwood: They go home at night, and they leave it up to us volunteers - our CFA (Country Fire Authority) to go and patrol at night, at two in the morning, putting their fires out that got away. And then they come back in the morning at nine o'clock and light them all up again for the heat of the day.

(Jill wanted it on record that SOME staff did good and that SOME very strategic and small-scale burning might have been useful to reduce the fire impact on private land before the main blow-up day, but the rest is rightful criticism.)

Sheila Newman, Interviewer: So you're saying that old growth forest ultimately went up? What about the argument though, that old growth forest doesn't usually burn easily and, as we remove it, we're increasing climate change? It seems to me that it would be better to have more old growth forest, less logging, to reduce the speed of climate change, even - and the risk of any forest fires.

Jill Redwood: That's logical! And that's what all the science is saying. But the government would prefer to keep the logging industry making that money, a few jobs - I think there's forty jobs involved in East Gippsland - but we're still destroying what has the ability to moderate our climate and that is forest. They're carbon capture and storage units - you know - the best in the world that we've got is our forests. They're knockign them down and creating these - you know - smoke, just ... ash landscapes with nothing there.

So the more that they log, the more that the climate is actually heating up, the less carbon there is stored in the forest, the less temperature moderation [2] there is over the landscape - and of course our bushfires are going to get much worse.

In the past, there has been - you know, lightening strikes - yes, South East Australia does get a lot of lightening strikes. Historically that's always been the case. Pre-European, pre-Aboriginal.

Sheila Newman, Interviewer: Yet there were very big forests.

Jill Redwood: They were very big forests and they had that structure where, you know, there are all these fire-breaks in the landscape. All the wet gullies, the south-facing slopes. The forest that had a lot of thick undergrowth. Where it wasn't thick undergrowth that stopped that stopped that heat and wind driving fires through, in some areas, just naturally it would open out and become dry sort of grassy understory forest. And that's what a lot of the early settlers described. But it wasn't due to burning. It was due to lack of burning. And that's what a lot of the science is now picking up. And we're [Sarcastically] just saying, 'Oh, no, the Aborigines used to burn so we've got to do the same to be safe!'

DEPI's 'Dangerous trees' policy

Sheila Newman, Interviewer: Coming up this way we've observed in the areas that have been really badly burned piles of fallen logs and tree-litter piled up - obviously by bulldozers and things.

Jill Redwood: What they are - and I've actually questioned this, and I've formally tried to get an answer - What they're doing now they have this 'dangerous trees' policy because all of these trees that are left standing along tracks are 'dangerous'. They might just fall on cars at any moment. So they have to go right along the tracks and cut down every tree that might possibly fall. And I've got photos of ones that are solid as a rock, not any rot in them, not leaning, and they've cut them down. And when they cut them down, of course, where you would have had a tree with a green leafy head and a trunk, you now have this pile of ... It's a tinder-box, waiting to burn, you know. And along the side of the roads. Like, hang on, weren't you trying to make the roads safer? And all they've done is bulldoze all of these trees and tree-heads up along the side of the road. So now, if there's another fire that comes through, they're just going to be this massive big bonfires.

Sheila Newman, Interviewer: How long has that been going on for, this business of cutting them down because they're 'dangerous'?

Jill Redwood: We just had that down here the year before ... yeah, 2013 they started doing that - down along Martin's Creek. In that area. So all of these habitat trees - the ones that are really important for habitat - feed trees for gliders, you know, the nectar producing trees, they're the best - the oldest ones are the best - cut them all down because they're 'dangerous'.

What are governments aiming for here?

Sheila Newman, Interviewer: Is there any idea - does anyone have any idea of what the governments - the successive governments - think they're doing with this area? Are they going to turn it into some plantation forest or, are they going to turn it into farmland? Or are they going to build appartments?

Jill Redwood: They're trying to turn it into plantations. That's what's been happening for the last forty years, it's conversion to plantations. But now the woodchip industry is starting to say, "Naw, we don't want those chips from South East Australia. Too far away. We'll get our woodchips from - you know - Vietnam - or somewhere else that's got the eucalypt plantations growing.

Fire[bug] Economy

So now, DEPI, who's had this agenda to create this wonderful woodchip farm for the Asian woodchip market for forty years, it's starting to fall in a heap. So: 'God, we've got to keep ourselves relevant, somehow - I know! Fire economy! Yes!'

And they call it 'Red gold' now, and the people at Glenaladale ...

Sheila Newman, Interviewer: Fire economy?

Jill Redwood: Fire economy! You know, keep DEPI relevant?

Sheila Newman, Interviewer: So, how are they doing this? What does 'fire economy' mean?

Jill Redwood: Well, it keeps the people employed burning, cutting down trees, bulldozing tracks ...

Sheila Newman, Interviewer: Oh, to 'prevent' bushfires and trees falling on people?

Jill Redwood: And if there is a bushfire - 'You beauty! We've got a lot of, you know, extra income for this, and we could employ our mates on bulldozers at $3000 a day to push tracks and push trees over and - oh, I don't know - you know, it might not be any good, but we've got to keep 'em employed and -

Sheila Newman, Interviewer: You'd think they could employ a few of them as forest rangers, wouldn't you?

Jill Redwood: Oh! Putting in picnic tables and walking tracks maybe might be a better thing but, you know, a lot of these boys do love their matches. And, you know, you look at the profile of a pyromaniac and, my God, I reckon that a lot of them would be perfect for those boys in green overalls and driving around in [?] vehicles.

Rare huge trees protected in EEG court case since felled for revenge

Jill Redwood: (Filmed standing by a huge fallen tree among several lining a fire track) All the way along here to our Brown Mountain forests - which was the test case in this court case - they have cut down every big tree along the way! There is no reason for it, other than -.

Sheila Newman, Interviewer: So these were the trees your court case [which was successful] was defending largely?

Jill Redwood: Yes!

Sheila Newman, Interviewer: They've all been cut down?

Jill Redwood: Yes! It's retribution. That's all it is. It's just absolute senseless destruction of giant big old trees.

Scale of destruction

Jill Redwood: (Back in home). I actually did a comparison between what's happening in the Amazon and what's happening in East Gippsland. And, relative to the area that we've got, and how much is being taken out each year, as clear-fell logs - clear-fell areas - it's pretty much on a par with the Amazon. It's just like ... East Gippsland is no better and here we are saying, 'World's best practice! It all grows back. All renewable!' It's not. It's bullshit! They are destroying what is irreplacable. Irreplacable! We have six hundred year old trees. We radiocarbon dated the wood from near the center of the tree. Six hundred year old trees! And it's just turned into this smokey, ashen landscape, and it goes of to - you know - Asian woodchip factories. If it was anywhere else in the world, they would be valuing these forests as something so rare. It would be the antiques of the natural world. And people would have to be paying big money to come and experience and stand amongst these giants and just be awestruck. But no - paper cups - throwaway paper!

[End transcript from short version of Firebug Economy film ("Pause and review wildlife and fire conf").]

NOTES

[1]

"Code of Destruction - A look at Victoria's future forest policy":

This film Recommends the creation of a "Great Forest National Park", where there would be no logging.

Prof. David Lindenmayer is one of Australia's foremost environmental experts. Over 30 years David has undertaken one of the most comprehensive scientific studies of a forest landscape anywhere in the world. With over 35 scientists and 2,500 volunteers they have painstakingly measured and tracked the Victorian central highlands. Now the state government who manages that forest refuses to reference their study as it presents a conclusion they are unwilling to hear. Without intention - all Victorians putting at risk their water security, biodiversity and the extinction of their fauna emblem - the endangered Leadbeaters Possum.

[2] Regarding the expression 'temperature moderation', this is a reference to more discussion in the longer version of this interview, covering the heat island effect and the cooling effect of forests, (particularly mature ones with big trees) which is noticable to anyone entering them. So, it is not just carbon storage, but the transpirational effects of forests (getting rid of heat and water, but also storing water - keeping the balance) and their shade that is important.

Yes, we’re still alive and kicking at https://eastgippsland.net.au/. We’ve been very preoccupied preparing another legal battle, but the good news is … our Supreme Court case which is arguing for effective Glider detection and protection, will begin this Monday (9th May). It’s scheduled to go for between 6-9 days and will be heard before the Honourable Justice Richards.

Yes, we’re still alive and kicking at https://eastgippsland.net.au/. We’ve been very preoccupied preparing another legal battle, but the good news is … our Supreme Court case which is arguing for effective Glider detection and protection, will begin this Monday (9th May). It’s scheduled to go for between 6-9 days and will be heard before the Honourable Justice Richards.

"Legal update for Gliders... Wildlife Act re-write... Protesters halt log traffic for 5 hours ... Giant tree found – 14m around ... NSW parliament unanimous against biomass burning..." Read the details inside.

"Legal update for Gliders... Wildlife Act re-write... Protesters halt log traffic for 5 hours ... Giant tree found – 14m around ... NSW parliament unanimous against biomass burning..." Read the details inside.

East Gippsland: VicForests is being very cooperative in giving

East Gippsland: VicForests is being very cooperative in giving  While EEG pulls out the legal artillery, GECO held up logging today by a tree-sitter cabled down to 5 machines – immobilising operations.

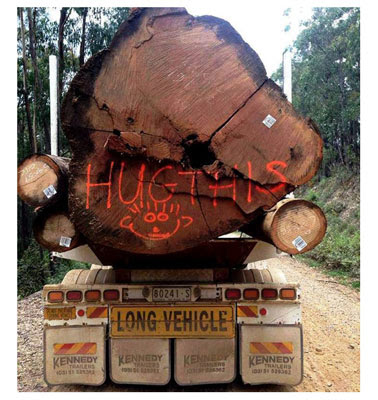

While EEG pulls out the legal artillery, GECO held up logging today by a tree-sitter cabled down to 5 machines – immobilising operations.  A logger recently posted this nasty message to forest activists on a day when they were meeting to negotiate the protection of giant trees.

A logger recently posted this nasty message to forest activists on a day when they were meeting to negotiate the protection of giant trees.

Environment East Gippsland (EEG) has won its fourth successful legal case, in a remarkable series for this David vs the Goliath of logging and destroying habitat. Over 2000 hectares have been set aside for owl habitat in a legal win for the owls. This was EEG's fourth Court case challenging the government's non-adherence to its own environment laws and it was settled on 17 July 2015, in favour of the owls!

Environment East Gippsland (EEG) has won its fourth successful legal case, in a remarkable series for this David vs the Goliath of logging and destroying habitat. Over 2000 hectares have been set aside for owl habitat in a legal win for the owls. This was EEG's fourth Court case challenging the government's non-adherence to its own environment laws and it was settled on 17 July 2015, in favour of the owls! How many more outrageous options for our state’s (planet’s) most valuable climate moderators and wildlife arks can they come up with?! Whole logs to China now. Not even processed (value added!) into woodchips. Has

How many more outrageous options for our state’s (planet’s) most valuable climate moderators and wildlife arks can they come up with?! Whole logs to China now. Not even processed (value added!) into woodchips. Has

Video and transcript inside This film, made for the conference exposes the lived experience of corrupt, stupid and lethal Victorian forest and fire management, despite and because of the 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission. The name of the film, "Firebug Economy," comes from Jill Redwood's description of a desperate way of making money out of fires by people in the declining logging business. In the film Jill also talks about the low flammability of old growth forests and the horrible synergy of forest removal, wildlife loss, and global warming, greatly accelerated under Victoria's 'planned burns policy'. Government policy has been stealthily converting old growth forests into plantations. Is the final aim is to sell them for farmland and urban development as Victoria burns? Please come to the Pause and Review conference in Melbourne 9th Nov 2014 at Kindness House, 288 Brunswick Street, Fitzroy Melbourne. Starts 10am. Contact: Maryland Wilson 0417 148 501. Jill Redwood of Environment East Gippsland is famous for leading the first ever successful case by an environmental organisation against a government logging firm. In this film we find that the trees granted protection in the famous EEG court case against VicForests have since been vengefully felled.

Video and transcript inside This film, made for the conference exposes the lived experience of corrupt, stupid and lethal Victorian forest and fire management, despite and because of the 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission. The name of the film, "Firebug Economy," comes from Jill Redwood's description of a desperate way of making money out of fires by people in the declining logging business. In the film Jill also talks about the low flammability of old growth forests and the horrible synergy of forest removal, wildlife loss, and global warming, greatly accelerated under Victoria's 'planned burns policy'. Government policy has been stealthily converting old growth forests into plantations. Is the final aim is to sell them for farmland and urban development as Victoria burns? Please come to the Pause and Review conference in Melbourne 9th Nov 2014 at Kindness House, 288 Brunswick Street, Fitzroy Melbourne. Starts 10am. Contact: Maryland Wilson 0417 148 501. Jill Redwood of Environment East Gippsland is famous for leading the first ever successful case by an environmental organisation against a government logging firm. In this film we find that the trees granted protection in the famous EEG court case against VicForests have since been vengefully felled.  Speakers include:

Speakers include:

Jill Redwood, as coordinator of Environment East Gippsland, conducted a landmark environmental court case that saw her group awarded damages against the Government Forestry corporation, VicForests, who were told to conduct proper investigations for the presence of threatened species in areas they logged and to design and enact plans to safeguard them according to the law. Three years later the Giant Trees Walk on Brown Mountain, which EEG had created in order to develop awareness of the rape of East Gippsland's forests, has been destroyed by persons unknown, equipped with heavy equipment and chainsaws.

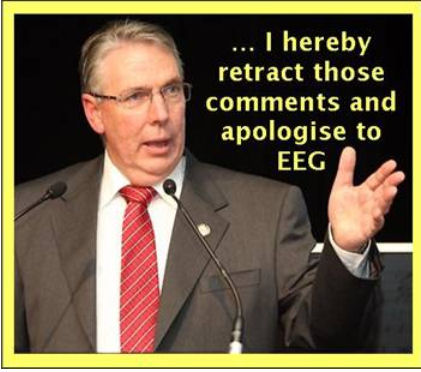

Jill Redwood, as coordinator of Environment East Gippsland, conducted a landmark environmental court case that saw her group awarded damages against the Government Forestry corporation, VicForests, who were told to conduct proper investigations for the presence of threatened species in areas they logged and to design and enact plans to safeguard them according to the law. Three years later the Giant Trees Walk on Brown Mountain, which EEG had created in order to develop awareness of the rape of East Gippsland's forests, has been destroyed by persons unknown, equipped with heavy equipment and chainsaws. Comments made against EEG last October have resulted in Minister Peter Walsh stepping back and making a public apology today, 19 March 2014. The apology to Environment East Gippsland was published on his parliamentary website. Peter Walsh is the Deputy Leader of the Victorian Nationals and Minister for Agriculture, Security and Water.

Comments made against EEG last October have resulted in Minister Peter Walsh stepping back and making a public apology today, 19 March 2014. The apology to Environment East Gippsland was published on his parliamentary website. Peter Walsh is the Deputy Leader of the Victorian Nationals and Minister for Agriculture, Security and Water.

AS I WRITE, the bulldozers and chainsaws are brutalising another superb stand of ancient forest not far from where I am just out of Orbost, south-eastern Victoria. (This article is an extract from one on the ABC. See inside for link.)

AS I WRITE, the bulldozers and chainsaws are brutalising another superb stand of ancient forest not far from where I am just out of Orbost, south-eastern Victoria. (This article is an extract from one on the ABC. See inside for link.)

A rally was held today on the steps of Parliament House in Melbourne " to protest against new laws proposed by the Napthine government which are undeniably bad news for forests.

A rally was held today on the steps of Parliament House in Melbourne " to protest against new laws proposed by the Napthine government which are undeniably bad news for forests.

"Oakeshott has been very vocal about the need to "challenge the power of money in politics" yet he seems to have been strongly influenced by the desperate native forest logging industry to support forest furnaces. We are very disappointed with his actions on this." (Prue Acton, Australian Forests and Climate Alliance.)

"Oakeshott has been very vocal about the need to "challenge the power of money in politics" yet he seems to have been strongly influenced by the desperate native forest logging industry to support forest furnaces. We are very disappointed with his actions on this." (Prue Acton, Australian Forests and Climate Alliance.)

VicForests must this week pay Environment East Gippsland $630,000 in legal costs which it incurred defending its wrong action in planning to destroy wildlife habitat forest in Australia. This, and a pending case also mentioned in this article, is a welcome indication of independence in Victoria's judiciary, despite wide corruption of the democratic system in Victoria and the rest of Australia.

VicForests must this week pay Environment East Gippsland $630,000 in legal costs which it incurred defending its wrong action in planning to destroy wildlife habitat forest in Australia. This, and a pending case also mentioned in this article, is a welcome indication of independence in Victoria's judiciary, despite wide corruption of the democratic system in Victoria and the rest of Australia. As a result of a peculiarity in the way Government works, the motion to call native forest furnace electricity ‘renewable energy’, has been sneakily placed on the 'non-controversial' list. That means that unless the Labor Government decides to force a vote, within days this back-door change in renewable energy policy could sneak through Parliament without there even being a vote!

As a result of a peculiarity in the way Government works, the motion to call native forest furnace electricity ‘renewable energy’, has been sneakily placed on the 'non-controversial' list. That means that unless the Labor Government decides to force a vote, within days this back-door change in renewable energy policy could sneak through Parliament without there even being a vote!

We were successful today! In fact even more so than we expected. The injunction phase was skipped and we’re going straight to trial now. It’ll be heard in April rather than Sept/Oct. as we were planning. This has to be good for us and the forests. This article has been retitled from "Injunction to stop logging of Cobb Hill rainforest Site." The teaser then was, "If this application is successful, it will be the third time VicForests will face the courts to be sued by a community group for what is believed to be illegal logging of protected areas of public forest."

We were successful today! In fact even more so than we expected. The injunction phase was skipped and we’re going straight to trial now. It’ll be heard in April rather than Sept/Oct. as we were planning. This has to be good for us and the forests. This article has been retitled from "Injunction to stop logging of Cobb Hill rainforest Site." The teaser then was, "If this application is successful, it will be the third time VicForests will face the courts to be sued by a community group for what is believed to be illegal logging of protected areas of public forest."

“Recently VicForests was caught out exporting whole logs, before that it was planned destruction of endangered wildlife habitat and currently the Ombudsman is investigating VicForests’ due processes." The industry is "in decline, with jobs on the line as the supply of trees dries up."

“Recently VicForests was caught out exporting whole logs, before that it was planned destruction of endangered wildlife habitat and currently the Ombudsman is investigating VicForests’ due processes." The industry is "in decline, with jobs on the line as the supply of trees dries up."  Radio program on the law and forests, featuring Jill Redwood and Slater and Gordon lawyer. Register for the Forests Forever Ecology Camp 22nd-25th April. How Japanese disasters have impacted on woodchipping industry.

Radio program on the law and forests, featuring Jill Redwood and Slater and Gordon lawyer. Register for the Forests Forever Ecology Camp 22nd-25th April. How Japanese disasters have impacted on woodchipping industry.

The ALP’s 2006 election promise was to protect ‘the last significant stands of old growth planned for logging’. But environment groups say that most of what has recently been identified for protecton was either in existing protection zones, had already been logged or was degraded forest unwanted for logs or woodchips anyway.

The ALP’s 2006 election promise was to protect ‘the last significant stands of old growth planned for logging’. But environment groups say that most of what has recently been identified for protecton was either in existing protection zones, had already been logged or was degraded forest unwanted for logs or woodchips anyway.

Recent comments