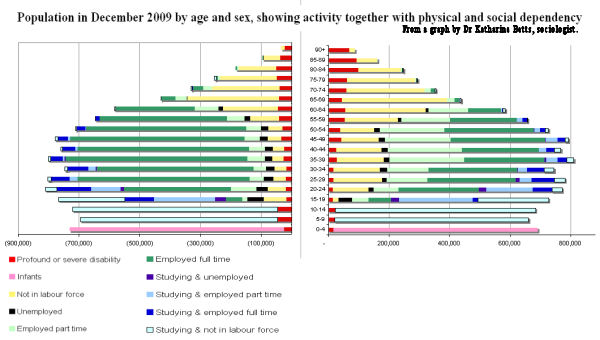

Discussing Australia's Dependency ratio 2009 with graph by Dr Katharine Betts

We look at Dr Katharine Betts's latest graph of ABS statistics on the ratio of working to dependent in Australia, noting that it is both untrue and discriminatory to imply that the 'Aged' are by far the biggest group of 'dependents.' In relation to the graph, we also look at the role of land-use planning and the social division of work in industrial society in creating financial dependencies where none previously existed. We note that established financial and institutional investment in the post-war industrial-contractual model makes it inflexible and resistant to changes in economic feedback, but that change it must as fossil fuels deplete. Left to their own devices, Australians would probably return to the human default social organisation around kin and place, which is flexible and low cost. This will only become possible, however, with cheaper land and an economic system which permits increasing relocalisation and more flexible use of land than the current plans for packed appartments and dense dormitory-suburbs anticipate.

We look at Dr Katharine Betts's latest graph of ABS statistics on the ratio of working to dependent in Australia, noting that it is both untrue and discriminatory to imply that the 'Aged' are by far the biggest group of 'dependents.' In relation to the graph, we also look at the role of land-use planning and the social division of work in industrial society in creating financial dependencies where none previously existed. We note that established financial and institutional investment in the post-war industrial-contractual model makes it inflexible and resistant to changes in economic feedback, but that change it must as fossil fuels deplete. Left to their own devices, Australians would probably return to the human default social organisation around kin and place, which is flexible and low cost. This will only become possible, however, with cheaper land and an economic system which permits increasing relocalisation and more flexible use of land than the current plans for packed appartments and dense dormitory-suburbs anticipate.

Click on above image to see larger full-size graph.

Sources: Disability, Ageing and Carers: Summary of Findings, Australia 2003, Catalogue no. 4430.0, ABS, Canberra, 2004; Labour Force, Australia, Detailed - Electronic Delivery, Catalogue no. 6291.0.55.001; General Social Survey 2006, Confidentialised Unit Record File supplied by the ABS.

Notes: The ABS defines a profound disability as one where the person always needs help with one or more of the activities involved in communication, mobility and self care, and a severe disability as one where the person sometimes needs such help.

The data on labour force participation are for December 2009, but detailed age break downs were only available for June 2009. All of the data have been standardised to the age/sex structure of the population in June 2009.

Graph and "Notes" (above) by Assoc. Prof. Dr Katharine Betts, (Swinburne University, Victoria) author of Immigration Ideology, MUP, 1988 and The Great Divide, Duffy and Snellgrove, 1999. She is also the co-editor, with Bob Birrell, of the Monash demographic quarterly, People and Place.

Introduction: We look here at Dr Katharine Betts's latest graph of ABS statistics on the ratio of working to dependent in Australia, noting that it is both untrue and discriminatory to imply that the 'Aged' are by far the biggest group of 'dependents.' In relation to the graph, we also look at the role of land-use planning and the social division of work in industrial society in creating financial dependencies where none previously existed. We note that established financial and institutional investment in the post-war industrial-contractual model makes it inflexible and resistant to changes in economic feedback. Left to their own devices, Australians would probably return to the human default social organisation around kin and place, which is flexible and low cost. This will only become possible, however, with cheaper land and an economic system which permits increasing relocalisation and more flexible use of land than the current plans for packed appartments and dense dormitory-suburbs anticipate.

Discussion

This is a complicated graph. Rather than start out looking for the greatest number of dependents, it is probably easier to look for the greatest number of full time then of part time workers. What is outside those full-time and part time workers gives you your main 'dependents'. Many of those are defined as dependent simply because they are not working in a paid job or deriving an income from a source in their own name. They may however be receiving support from a partner, such as a husband, while they are rearing children. In addition, many of the students aged 15 and over have paid jobs, some of them full-time.

However the real dependents are those who are literally unable to work.

Dependency is defined economically, by material income and paid work or the ability to participate in getting an income, and it carries a stigma, since it is assumed that 'dependent persons' cost the taxpayer. Although we know that many women do an enormous amount of unpaid work in the home as mothers, partners and grandmothers and as volunteers, if we only count people in paid work as making an economically useful contribution, this unpaid work is overlooked. (The ABS does know about this problem; they don't mean to denigrate domestic work). If dependent means not in paid work, women are the largest 'dependent' category at all ages (even in infancy, because more survive).

How the growth lobby misrepresents the ratio of dependency

Because the growth lobby likes the idea of women having lots of children, there is a tendency to misrepresent dependency as only occurring among the elderly.

We can see, in fact, that the numbers of officially totally dependent people (the red category) remain quite small in all cohorts. These are people who, because of some disability, need help from others in order to cope with tasks of daily living, such as washing and dressing. We can also see that the largest totally dependent category- pink and pale turquoise with border - are not actually classified as such at all. They are classified as infants or students. [Due to possible confusion of similar colours, let us precise here that light blue, as opposed to turquoise with border, represents students who are employed part-time.]

It looks like the government’s and the growth lobby's constant use of 'Aged' as virtually synonymous with 'dependents' is a blatant case of age discrimination, since it implies that elderly people are by far the biggest group of the totally dependent.

There is another group in yellow which isn’t in paid employment. From the age of 60 the yellow category starts to get quite large. That doesn’t mean that it is ‘dependent’. The people in the yellow category are living by some means – probably through superannuation, pension or investments.

Much larger, however, are the pale turquoise and pink categories. These categories extend over the first 15 to 20 years of a person's life. [1]

The non-dependent categories

The green categories – i.e. the ‘employed’ – both part-time and full-time – are considered to be supporting the yellow, the red, the pink and the pale turquoise with border categories. From a purely financial perspective, it doesn't matter if they are generating taxes to support babies, students, homemakers, disabled people or elderly infirm people.

Some people worry that if the number of new babies dwindles, there won't be enough people moving up from the bottom of the pyramid to carry the dependencies that increase at the top. They forget that if a population has a smaller base than middle, that means that by the time the people in the middle stop working and the smaller population base enters the workforce, the competition for land will have reduced, so the cost of living will be much less. This will reduce the cost of funding retirees.

Positive economic impact of decrease in number of young dependents

Also to be considered is the fact that, as the proportions of pink and pale turquoise infants and full-time students decrease, so will the burden on taxpayers. Schools, child-care and health and welfare services for the young are supported by taxpayers, just as are old age pensions. But children also involve heavy private costs for their parents. And often this means that parents have to forgo earned income, as they stay out of the labour force in order to provide care. Of course children bring many intangible benefits to their parents, but from the point of view of time and money, there would be more resources for other needs if we had rather fewer of them.

With regard to the yellow categories, just because they are not in paid employment, it does not mean that they are not doing something useful. Wives or husbands support their working partner by looking after house and garden, growing food, doing accounts, looking after children, and participating in the community. Many grandparents may also look after children so that parents can work, or they provide knowledge, experience and an example to the community. Elderly people are the eyes and ears in a street where everyone else goes to work all day. There are also so many things which need attention in our society and housewives/husbands and elderly people and the unemployed are among the ones free to participate in groups monitoring the environment and political developments at all levels.

Dependency and Variations in the Social division of work and land-use planning systems

Australia's industrial social organisation and its land-use planning system have also come to mean that the extended family, with which the responsibilities of earning a living, raising a family and participating in the politics of one's community were formerly shared, has become disorganised and dysfunctional. This is not, as is often suggested, simply because Australians are 'selfish'. The early and strong continuing urbanisation of Australian society, with drift to big cities in search of work, harsh expectations of relocation along with one's employer, and migration from one country to another or one end of Australia to the other end, splinters clans from their original location, isolates nuclear families and splits up parents and children. This makes most of us ever-more-dependent on the industrial models of salaried employment, bank loans and insurance, new housing, and, notably, contractual nurturing, caring, and nursing arrangements. The industrial state has adapted to try to mitigate this fragmentation and fracture of human social systems, in formal 'social services', which it finances through much higher taxes than in pre-WW2 years. If these professionalised and contractualised services are privately contracted, they need somehow to make a profit, which also raises the costs of dependency, as we see in child-care centers and private nursing homes.

Established financial and institutional investment in this industrial contractual model makes it resistant to change, but change it must, in the face of declining margins of profit associated with declining availability of cheap and abundant fossil fuels. It is not surprising that the state is concerned about its ability to provide for 'dependent' Australians, but it should be able to recognise how the system it relies on has created more dependency and more expensive dependency. Left to their own devices, Australians would probably return to the default social organisation around kin and place, which is flexible and low cost. This will only become possible, however, with cheaper land and an economic system which permits increasing relocalisation and more flexible use of land than the current plans for packed appartments and dense dormitory-suburbs anticipate.

Notes

[1] This span of years of dependency of youth could well expand in the future if the industrial employment model doesn't last as which have tended to last for something like 20 years.

Note that finishing study, around the age of 15 or 20, does not necessarily mean an end to 'dependence'. Dependence, in the form of 'unemployment' could well expand in the future if the industrial employment model doesn't last as depletion of fossil fuel progresses. Partial dependence could expand through categories if median wages are unable to afford unsubsidised accomodation or food, power and water if land-prices continue and push up the cost of everything else.

Recent comments