In her marvellously lucid book, Wilful Blindness, Margaret Heffernan, writes about the institutionalisation of denial in the service of profit, the acquisition of wealth, and the defence of personally comforting ideologies. "Bandura has spent a lifetime dissecting the moral disengagement required for the perpetration of criminal and inhuman acts, a journey that has taken him from the tobacco industry, the gun lobby, the television business to the multiple industries implicated in environmental degradation. He has a deep understanding of the forces at work which encourage employees to be blind to their collusion in these processes. But nothing enrages him more than the economic justifications used to defend continued population growth."

In her marvellously lucid book, Wilful Blindness, Margaret Heffernan, writes about the institutionalisation of denial in the service of profit, the acquisition of wealth, and the defence of personally comforting ideologies. "Bandura has spent a lifetime dissecting the moral disengagement required for the perpetration of criminal and inhuman acts, a journey that has taken him from the tobacco industry, the gun lobby, the television business to the multiple industries implicated in environmental degradation. He has a deep understanding of the forces at work which encourage employees to be blind to their collusion in these processes. But nothing enrages him more than the economic justifications used to defend continued population growth."

'Wilful blindness' is an English legal concept that arose in a 19th century case where a person could not be convicted of stealing government property unless they either knew where the property came from or they had 'wilfully shut their eyes' to its origin. Modern travellers are asked to sign declarations that they are aware of the contents of their suitcases, which may then be used against them if illegal drugs come to light during customs searches. Not knowing was also no defence for the guilty in the Enron trials. Legally it doesn't matter whether or not your knowledge was unconscious, but outside the courts you can still get away with manslaughter and dispossession for commercial purposes by kidding yourself and you will find that most people in the community will back you right up.

An amazing list of almost unbelievable (but well-documented) wilful blindnesses

Heffernan examines a remarkable list of wilful blindnesses that have caused innumerable deaths and other highly adverse circumstances. Most of her cases are huge and massively documented, yet a number were quite unknown to me. Her book is a remarkable document for that reason, of enormous use for the political and social researcher, as well as a jolly good read. Among the cases she examines in detail are:

- childhood cancer and foetal X-rays. The very strong link and occurrence was proven for decades yet doctors continued to X-ray pregnant women until the mid-1980s.

- Enron and how everyone there looked the other way

- asbestosis and how an entire town was moribund but refusing to face the cause in the local mine, instead ill-treating the only woman in the town who tried to fight the mine

- Greenspan before Congress, finally admitting his market-ideology was flawed

- Avoidable collisions of battleships where officers followed a captain's orders even though they knew these would cause two ships to collide

- Hospitals that protected an incompetent surgeon and ostracised the doctor who tried to stop him

- BP's remarkable record of ignoring safety regulations and orders and causing death among workers before it even came to Deepwater Horizon.

Margaret Heffernan asks why whistleblowers and Cassandras are so rare, when they save lives and communities often simply by stating the obvious over and over again. She writes on the several ways individuals become deliberately blind by denial of painful truths, interspersing her political and social case studies with records of psychological experiments and theory.

Wilful Blindness and the Population Growth Lobby

Hearing of this wilful blindness legal concept, before I read the book, I wondered how it might apply to those who maintain the growth lobby for their own and corporate profit against democratic wishes of the majority and in the face of costs it imposes on individuals and communities. On reading the book I was very interested to read the following about overpopulation, in which she quotes another clear thinker, Professor Bandura, of Stanford University.

“No one visiting Stanford University could fail to be impressed by its sheer scale or its wealth. Over twelve square miles, it's ten times larger than Vatican City and the vast avenues of palms leading to fountains and Spanish courtyards are reminiscent more of Renaissance papal power play than 21st-century cutting-edge research. Such lavish public buildings feel brash in their confidence, but their rooms harbour perpetrators of doubt and scepticism. At the heart of the campus, ensconced in an unremarkable lino-floored, booklined room, sits Albert ‘Al’ Bandura. In many respects, Bandura is the grand old man of psychology: its most cited living author, the father of social-learning theory and one of the first people to argue that children's behavior derived not just from reward and punishment but horn what they observed around them. That this seems such an obvious thought to us nowadays is testimony to how profound Bandura's impact has been on our thinking. The very phrase 'role model' would scarcely exist without him.

Much of Bandura's work has so seeped into public consciousness that we are barely aware that it is there, and his work has attracted scores of awards, honours and distinctions. But today, at the age of eighty-five, this hasn't stopped him working, nor has it rendered him complacent. For all his eminence, he's an engaging and accessible man whose mild manner belies a tenacious mind. And one of the issues he has wrestled with for years is the process by which individuals lose sight of morality in their need to preserve their sense of self-worth.

‘People are highly driven to do things that build self-worth; you can't transgress and think of yourself as bad. You need to protect your sense of yourself as good. And so people transform harmful practices into worthy ones, by coming up with social justification, by distancing themselves with euphemisms, by ignoring the long-term consequences of their actions.’

One of the most prominent ways in which people justify their harmful practices is by using arguments about money to obscure moral and social issues. Because we can't and won't acknowledge that some of our choices are socially and morally harmful, we distance ourselves from them by claiming they're necessary for wealth creation. Nowhere is this more dangerous, he argues, than in our attitudes to the environment and population growth. The easiest way for those who resist calls to curb population growth, and who oppose environmental controls, is to represent themselves as the good guys because they just want to make everyone better-off.

'To defend their positions, they can't say "Sure, we're the bad guys and we want to rape and pillage the planet",’ Bandura told me. 'They have to vindicate harmful practices that take such a heavy toll on the environment and the quality of human life-they have to make out that what's harmful is, in fact, good. And one way they do that is to use the notion of nature as, in fact, an economic commodity. So they see nature in terms of its market value rather than its inherent value.'

That's why, Bandura argues, those who claim to love nature can also support, for example, drilling for oil in Alaska. They can't see themselves as destroyers, so they position themselves as the rational liberators of natural wealth. In this vein, Bandura quotes Newt Gingrich: 'To get the best ecosystem for our buck, we should use decentralised and entrepreneurial strategies.' Similarly, when China signed a multi-billion-dollar deal with the Indonesian Government to clearcut four million acres of forest, in order to replace it with palm-oil plantations, a clan elder could not conceive of himself as doing the wrong thing. As he put it succinctly, 'Wood is gold.' It is, says Bandura, the economic justification that makes the environmentally damaging decision possible. Seeing nature as just a source of money blinds such decision makers to the moral consequences of their decisions.

Bandura has spent a lifetime dissecting the moral disengagement required for e perpetration of criminal and inhuman acts, a journey that has taken him from the tobacco industry, the gun lobby, the television business to the multiple industries implicated in environmental degradation. He has a deep understanding of the forces at work which encourage employees to be blind to their collusion in these processes. But nothing enrages him more than the economic justifications used to defend continued population growth.

'I went to a conference in Germany,' Bandura recalled, 'where a young African woman spoke about the tremendous difference that birth control and health education had had on her community. The fact that she and her peers now had control over the number of children that they conceived and raised had transformed their lives. And she spoke of this very eloquently. And there, in that audience of well-heeled Europeans, rich Westerners, she was booed!'

When he recovered from his shock, Bandura analysed what was going on in the minds of the audience. What drove them, he reasoned, was their recognition that Western birth rates won't pay for the pension requirements of the elderly; if the West doesn't produce more children, it can't produce the wealth needed to look after parents when they retire. Therefore, even though consumption and environmental degradation are clearly linked, the needs of the market trump the needs of the planet.

Nor was this a purely Western phenomenon. The need for money effectively positions infants as money-making machines.

In some countries (Bandura writes], the pressure on women to boost their childbearing includes punitive, threats as well. The former prime minister of Japan, Yoshiro Mori, suggested that women who bore no children should be barred from receiving pensions, saying 'It is truly strange to say we have to use tax money to take care of women who don't even give birth once, who grow old living their lives selfishly and singing the praises of freedom.' In this campaign for more babies, childbearing is reduced to a means for economic growth.

In this mindset, children are nothing more than money-makers in the eyes of politicians merely crunching the numbers, blind to the moral, environmental or humanitarian consequences of their policies. Market thinking has obliterated moral thinking on a grand scale.

So persuasive (and pervasive) has the economic argument in favour of population growth become, says Bandura, that all of the major NGOs have had to stand aside from it. Fear of alienating donors, criticism from the progressive left and disparagement by conservative vested interests claiming that overpopulation is a 'myth' served as further incentives to cast off the rising global population as a factor in environmental degradation. Population growth vanished from the agendas of mainstream environmental organisations that previously regarded escalating numbers as a major environmental threat. Greenpeace announced that population ‘is not an issue for us’. Friends of the Earth declared that 'it is unhelpful to enter into a debate about numbers'. The fear of losing money disabled those very organisations best placed to understand the ultimate consequences of thinking only about money.

What money does, Bandura argues, is allow us to disengage from the moral and social effects of our decisions. As long as we can frame everything as an economic argument, we don't have to confront the social or moral consequences of our decisions. That economics has become such a dominant, if not the prevalent, mindset for evaluating social and political choices has been one of the defining characteristics of our age. As long as the numbers work, we feel absolved of the harder, more inchoate ethical choices that face us none the less. We appear to have gone from having a market economy to being a market society (if that isn't an oxymoron) and it's an interesting thought that our obsession with economics has just been one long sustained phase of displacement activity.

Money is just one of the forces that blind us to information and issues which we could pay attention to - but don't. It exacerbates and often rewards all the other drivers of wilful blindness: our preference for the familiar, our love for individuals and for big ideas, a love of busyness and our dislike of conflict and change, the human instinct to obey and conform and our skill at displacing and diffusing responsibility. All of these operate and collaborate with varying intensities at different moments in our lives. The common denominator is that they all make us protect our sense of self-worth, reducing dissonance and conferring a sense of security, however illusory. In some ways, they all act like money: making us feel good at first, with consequences we don't see. We wouldn't be so blind if our blindness didn't deliver rewards: the benefit of comfort and ease.

But in failing to confront the greatest challenge of our age - climate change - all the forces of wilful blindness come together, like synchronised swimmers in a spectacular water ballet. We live with people like ourselves, and sharing consumption habits blinds us to their cost. Like the unwitting spouse of an alcoholic, we know there's something amiss but we don't want to acknowledge that the lifestyles we love may be killing us. The dissonance produced by reading about our environmental impact on the one hand, and living as we do, is resolved by minor alterations in what we buy or eat, but very few significant social shifts. Sometimes we get so anxious we consume more. We keep too busy to confront our worries, a kind of wild displacement activity with schedules that don't allow us to be as green as we'd like. The gravitational pull of the status quo exerts its influence and global conferences end when no one has the stomach for the levels of conflict they engender. In our own countries, no politician shows the nerve for the political battles real change would require.

We're obedient consumers and we might change if we were told to, but we're not. We conform to the consumption patterns we see around us as we all become bystanders, hoping someone else somewhere will intervene. Our governments and corporations grow too complex to communicate or to change and we are left just where we do not want to be, where our only consolation is cash.

This is wilful blindness on a spectacular scale and it would leave us abject with despair, were it not that, all around us, are individuals who aren't blind. That they can and do see more, and act on what they see, offers a possibility that we can be wilfully sighted too.”

Most interesting and alarming of all, despite all of these cases and situations being well known and recognised at academic or legal level, the general public remains in the dark because somehow, these lessons learned are never institutionalised for our collective good. With rare exceptions politicians, governments and the mass media, continue to maintain fictions blown apart time and again, because they have a vested interest. Somehow, somewhere, this time, they maintain, it will be different.

I was particularly struck, as an Australian, by how the following statement sums up what is happening in Australia:

"In this mindset, children are nothing more than money-makers in the eyes of politicians merely crunching the numbers, blind to the moral, environmental or humanitarian consequences of their policies. Market thinking has obliterated moral thinking on a grand scale."

And it has obliterated democracy in Australia - aided and abetted by 'moral' books that seem wilfully blind to the focused benefits that population growth brings to the growth lobby, like Ian Angus and Simon Butler's, Too many people, Haymarket Books, Chicago, 2011, published with the help of the US-based Lannan Foundation and the Wallace Global Fund. It seems true to say that, if you'll defend controlling population upwards, you can always find a wealthy sponsor.

Some wealthy homemakers are being allowed to do the opposite of what the rest of us are being told to do. They have been given permission to turn an area where there were six households into one - theirs. Such significant destruction and prioritization of certain interests in the face of so much homelessness and the loss of democracy for all Victorians through authoritarian planning is shocking.

Some wealthy homemakers are being allowed to do the opposite of what the rest of us are being told to do. They have been given permission to turn an area where there were six households into one - theirs. Such significant destruction and prioritization of certain interests in the face of so much homelessness and the loss of democracy for all Victorians through authoritarian planning is shocking.

A predictably

A predictably  One of the many, many signs that Australia is nothing more than a US military and intelligence asset is the way its government has consistently refused to intervene to protect Australian citizen Julian Assange from political persecution at the hands of the US empire.

One of the many, many signs that Australia is nothing more than a US military and intelligence asset is the way its government has consistently refused to intervene to protect Australian citizen Julian Assange from political persecution at the hands of the US empire.

"Official Western institutions have never recognised Assange as a prisoner of conscience,why do you think that is?" Oksana asks Greg Barnes. After almost a decade in confinement, Julian Assange is still fighting against extradition requests to the United States, at cost to his physical and mental health, while also compromising WikiLeaks’ ability to continue its operations.

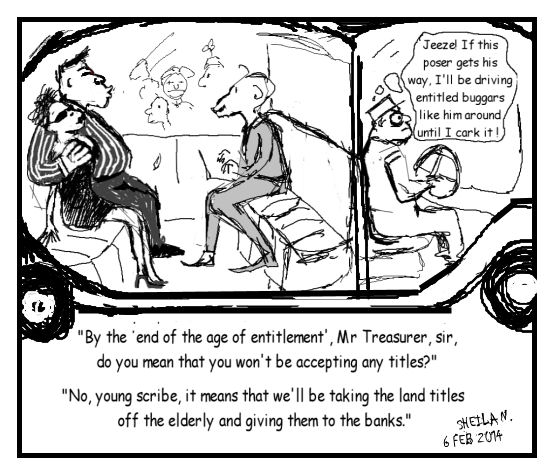

"Official Western institutions have never recognised Assange as a prisoner of conscience,why do you think that is?" Oksana asks Greg Barnes. After almost a decade in confinement, Julian Assange is still fighting against extradition requests to the United States, at cost to his physical and mental health, while also compromising WikiLeaks’ ability to continue its operations. “Merely adding more people isn’t a sustainable economic strategy. We can’t pretend that high immigration comes without a cost and growth should not impose an unfair burden on those who are already here. Excessively rapid growth puts downward pressure on wages and upward pressure on housing prices, both of which have sorely stung workers and aspiring home-owners in Sydney and other parts of NSW for a decade. When you look at the numbers, it’s no surprise communities in Sydney are feeling the pressure. In 2006, annual net overseas migration to Australia increased to roughly double its pace across the preceding 25 years.” (Dominique Perrottet as Treasurer in 2018)

“Merely adding more people isn’t a sustainable economic strategy. We can’t pretend that high immigration comes without a cost and growth should not impose an unfair burden on those who are already here. Excessively rapid growth puts downward pressure on wages and upward pressure on housing prices, both of which have sorely stung workers and aspiring home-owners in Sydney and other parts of NSW for a decade. When you look at the numbers, it’s no surprise communities in Sydney are feeling the pressure. In 2006, annual net overseas migration to Australia increased to roughly double its pace across the preceding 25 years.” (Dominique Perrottet as Treasurer in 2018)

In this video, BBC journalist Orla Guerin interviews Azerbaijan President Aliyev, assuming that Azerbaijan press and politics are heavily censored, and presses him on that. He denies the accusation, then asks her why Julian Assange has been held inhumanely for years, if the British and western press are so free. The BBC journalist simply won't acknowledge the situation for journalists and the media in her own country, kind of proving the president's point.

In this video, BBC journalist Orla Guerin interviews Azerbaijan President Aliyev, assuming that Azerbaijan press and politics are heavily censored, and presses him on that. He denies the accusation, then asks her why Julian Assange has been held inhumanely for years, if the British and western press are so free. The BBC journalist simply won't acknowledge the situation for journalists and the media in her own country, kind of proving the president's point. Scott Morrison

Scott Morrison

GetUp is seeking donations to fund its unscientific campaign to magically transform one of the world's most rapidly expanding and extreme carbon based economies by adopting Renewable Energy Targets and other forms of financial incentives to encourage use of alternative energy while fully supporting the extreme population growth that is the driving force behind the rapid expansion of Australia's carbon emissions.

GetUp is seeking donations to fund its unscientific campaign to magically transform one of the world's most rapidly expanding and extreme carbon based economies by adopting Renewable Energy Targets and other forms of financial incentives to encourage use of alternative energy while fully supporting the extreme population growth that is the driving force behind the rapid expansion of Australia's carbon emissions.

It is said that Marie Antoinette, wife of King Louis XVI, when confronted with the fact that people had no bread, said, "Let them eat cake, then." This story is supposed to illustrate how out of touch Marie-Antoinette was - so much so that she could not see the absurdity of her pronouncement - which was that she was rich but the people were starving. Australia has a whole slew of Marie-Antoinettesque politicians who peddle fundamentalist global economic policies, apparently with no idea at all of how angry people are becoming about being treated like children with no rights to self-government at all.

It is said that Marie Antoinette, wife of King Louis XVI, when confronted with the fact that people had no bread, said, "Let them eat cake, then." This story is supposed to illustrate how out of touch Marie-Antoinette was - so much so that she could not see the absurdity of her pronouncement - which was that she was rich but the people were starving. Australia has a whole slew of Marie-Antoinettesque politicians who peddle fundamentalist global economic policies, apparently with no idea at all of how angry people are becoming about being treated like children with no rights to self-government at all.

In her marvellously lucid book,

In her marvellously lucid book,

October 31st, 2011, was a "teachable" moment, one of those moments that come so infrequently that they must therefore be seized and exploited to the fullest extent to increase public awareness. That was the day that, according to demographers, we reached an awful milestone, the day that our species became 7 billion in number. If you expected David Suzuki to use that event to highlight the problem of overpopulation, your expectations would have been cruelly dashed. Dr. Suzuki instead chose to spout the Monbiot line. Overpopulation is not the problem, you see. Its overconsumption by you know who.

October 31st, 2011, was a "teachable" moment, one of those moments that come so infrequently that they must therefore be seized and exploited to the fullest extent to increase public awareness. That was the day that, according to demographers, we reached an awful milestone, the day that our species became 7 billion in number. If you expected David Suzuki to use that event to highlight the problem of overpopulation, your expectations would have been cruelly dashed. Dr. Suzuki instead chose to spout the Monbiot line. Overpopulation is not the problem, you see. Its overconsumption by you know who.

The Canadian federal election cries out for an alternative to BAU growthism. It cries out for a party which would present a coherent and distinctive alternative to the system of economic growth. Canadians need a place on the ballot where they can mark an "X" beside "no more growth". In fact they need an opportunity for vote for "de-growth". But the Green Party of Canada is not providing them with that opportunity or alternative. Instead, what they are providing is meaningless rhetoric and platitudes. Shall we lend credence to their approach by voting for them? Shall we allow them to say that they have our support for their direction? Shall we allow them to say, after receiving our vote, that they have a mandate to push for hyper immigration and a foreign aid policy that would continue to promote global overpopulation? I say no. I say that casting a vote can sometimes be worse than spoiling a ballot. There are many things one can do to promote change that voting in a sham election. Writing, petitioning, demonstrating and educating the grassroots come to mind.

The Canadian federal election cries out for an alternative to BAU growthism. It cries out for a party which would present a coherent and distinctive alternative to the system of economic growth. Canadians need a place on the ballot where they can mark an "X" beside "no more growth". In fact they need an opportunity for vote for "de-growth". But the Green Party of Canada is not providing them with that opportunity or alternative. Instead, what they are providing is meaningless rhetoric and platitudes. Shall we lend credence to their approach by voting for them? Shall we allow them to say that they have our support for their direction? Shall we allow them to say, after receiving our vote, that they have a mandate to push for hyper immigration and a foreign aid policy that would continue to promote global overpopulation? I say no. I say that casting a vote can sometimes be worse than spoiling a ballot. There are many things one can do to promote change that voting in a sham election. Writing, petitioning, demonstrating and educating the grassroots come to mind. The Canadian federal election is upon us and the Green Party claims to offer a "significantly different approach to governance" (see below). Really? Let's take a look:

The Canadian federal election is upon us and the Green Party claims to offer a "significantly different approach to governance" (see below). Really? Let's take a look:

Recent comments