Churches are part of politics and usually back the establishment, as much through investment in property assets as through political policy. It is therefore inspiring to see this honorable departure from the mainstream church and mass-media-led arguments for population growth. In March 2009 the Public Affairs Commission released this discussion paper on key issues for Australia’s future, which recommended some responses to global and national environmental stresses. A summary of this paper is attached, with a reference to the General Synod web site where the whole paper may be accessed.

The author of this paper is John Langmore, an Anglican and ex-ALP senator ffrom the ACT. It is a very worthy contribution to the "Population Debate". We present here the original document that gave rise to some sensational reporting, such as "Anglican Church accused of paganism, advocating genocide". Our publishing of this paper does not mean that candobetter.org has any religious affiliation or belief. (Candobetter.org editor)

Prepared by the Public Affairs Commission

of the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Australia

March 2010

In March 2009 the Public Affairs Commission released a discussion paper on key issues for Australia’s future, which recommended some responses to global and national environmental stresses. A summary of this paper is attached, with a reference to the General Synod web site where the whole paper may be accessed.

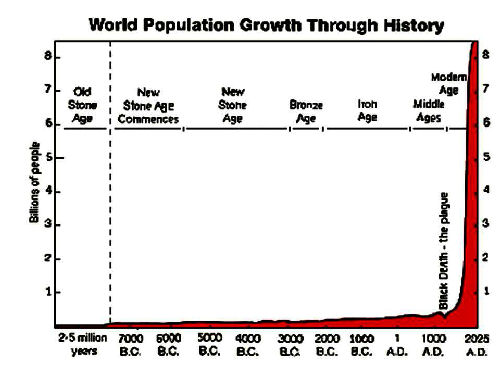

Now the Commission seeks to assist consideration of population growth in a way that is consistent with our Christian faith and it is hoped will encourage integrated responses. Population growth is a controversial and sensitive topic, and one about which many fear to speak publicly, but it is fundamental to the challenges we face, globally and in Australia. Globally there is concern about the projected increase in population from 6.8 billion now to 9.2 billion by 2050 (1). In Australia there is concern about the recent official projection that Australia’s population will increase from 22 million now to 35 million by 2050. Consumption and environmental impact increase with population. These population increases will be taking place in a finite world that has not yet been able to agree on reducing greenhouse gas emissions enough to avoid potentially catastrophic temperature increase and climate change. There is hope: a serious debate about population growth has very recently begun in Australia. This paper provides a brief overview and encouragement for Christians to become informed on the issue and to contribute to the debate.

1. What responsibility do we bear as Christians?

Most people in developed countries, including Australia, have benefited hugely from the resources of the Earth. Until recently we did not have compelling evidence of the problems caused by the growth in human numbers and consumption, but now we do. Our awareness makes us responsible to do our best for the future. This is not about guilt for the past, but about responsibility for the future. We continue to celebrate the joys of children, families, communities, and the wonderful natural world around us but now, in words from Lambeth, with a much clearer awareness of our <‘God given mandate to care for, look after and protect God's creation’ (see below), and a focus on the beautiful expression of Thanksgiving 5 in our Prayer Book:

‘Loving God, we thank you for this world of wonder and delight,

You have given it to us to care for, so that all your creatures may enjoy its bounty,

Lord our God, we give you thanks and praise.’

The Commission commends the following statement prepared by the Environment Working Group of the Australian Anglican General Synod, in the context of action concerning the Canon for Protection of the Environment which was passed by the 14th General Synod (2007), accessible on the General Synod web site and attached to this paper.

‘The bond between Creator and creation underlies our whole relationship with God and it is clear from scripture that this bond is not just with humanity but with the whole of creation (e.g. John 1: 3; Romans 8: 20-21). As a consequence, it is essential that the Church takes this relationship seriously and seeks to express it rightly and fully, remembering that those whose words result in relevant action are blessed (James 1: 22-25). Our generation is faced with the dual threats of human induced climate change and the highest extinction rate in human history. In recognising that God sustains and saves all creation, and appoints people as stewards, we are called to honour God through acting with care and respect not only for other people but for all the earth. As the declaration to the Anglican Communion of the 2002 Global Congress on the Stewardship of Creation argues, “We come together as a community of faith. Creation calls us, our vocation as God's redeemed drives us, the Spirit in our midst enlivens us, scripture compels us.” This is echoed in the 2007 Canon for the Protection of the Environment, which points out that “In Genesis it says that ‘The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till and to keep it’. In 1990 the Anglican Consultative Council gave modern form to this when it declared that one of the five marks of the mission of the church was ‘to strive to safeguard the integrity of creation, and to sustain and renew the life of the Earth’.’

To this may be added that unless we take account of the needs of future life on Earth, there is a case that we break the eighth commandment – ‘Thou shalt not steal’. Christians are sometimes regarded by those outside the church as caring only about their own spiritual wellbeing to the exclusion of valuing and caring for the whole of life on Earth (2, pp. 5-6). In contrast, we draw attention here to very clear statements on the public record from our church leadership at the highest level:

The resolutions from the 1998 Lambeth Conference (of the Bishops of the world-wide Anglican Communion, convened by the Archbishop of Canterbury) included the following strong statement:

i. that unless human beings take responsibility for caring for the earth, the consequences will be catastrophic because of:

overpopulation

unsustainable levels of consumption by the rich

poor quality and shortage of water

air pollution

eroded and impoverished soil

forest destruction

plant and animal extinction;

ii. that the loss of natural habitats is a direct cause of genocide amongst millions of indigenous peoples and is causing the extinction of thousands of plant and animal species. Unbridled capitalism, selfishness and greed cannot continue to be allowed to pollute, exploit and destroy what remains of the earth's indigenous habitats;

iii. that the future of human beings and all life on earth hangs in balance as a consequence of the present unjust economic structures, the injustice existing between the rich and the poor, the continuing exploitation of the natural environment and the threat of nuclear self-destruction;

iv. that the servant-hood to God's creation is becoming the most important responsibility facing humankind and that we should work together with people of all faiths in the implementation of our responsibilities;

v. that we as Christians have a God given mandate to care for, look after and protect God's creation.

In this Resolution, ‘overpopulation’ is the first-named reason for concern about the risks of catastrophic consequences for the earth. Resolutions from the Lambeth Conferences reaffirm the Biblical vision of Creation as a ‘web of inter-dependent relationships bound together in the Covenant which God has established with the whole earth and every living being’. They state that ‘human beings are …. co-partners with the rest of Creation ….with responsibility to make personal and corporate sacrifices for the common good of all Creation’. Relevant resolutions from the 1998 and 2008 Lambeth Conferences are attached in full to the March 2009 PAC paper.

On 13 October 2009 in the lead-up to the Copenhagen conference on climate change, the Archbishop of Canterbury set out a Christian vision of how people can respond to the looming environmental crisis (3). He said that ‘living in a way that honours rather than threatens the planet is living out what it means to be made in the image of God. We do justice to what we are as human beings when we seek to do justice to the diversity of life around us; we become what we are supposed to be when we assume our responsibility for life continuing on earth. And that call to do justice brings with it the call to re-examine what we mean by growth and wealth.’ Then ‘Our response to the crisis needs to be, in the most basic sense, a reality check, a re-acquaintance with the facts of our interdependence with the material world and a rediscovery of our responsibility for it. And this is why the apparently small-scale action that changes personal habits and local possibilities is so crucial. When we believe in transformation at the local and personal level, we are laying the surest foundations for change at the national and international level.’ Part of this is to ‘change our habits enough to make us more aware of the diversity of life around us’, make sure we watch the changing of the seasons on the earth’s surface, and ‘ask constantly how we can restore a sense of association with the material place and time and climate we inhabit and are part of…. The Christian story lays out a model of reconnection with an alienated world’.

In tune with this is the earlier writing of the cultural historian and eco-theologian Thomas Berry, offering a new perspective that recasts our understanding of science, technology, politics, religion, ecology and education. He shows why it is important for us to respond to the need for renewal of the earth, and suggests what we must do (particularly through education) to break free of the drive for a misguided dream of progress. His book ‘ The Dream of the Earth’(4) shows how the convergence of modern science and spiritual and religious affinity for creation can lead to a new covenant of ethical responsibility for the natural world. In this, science is seen not in its familiar role of taking the earth apart so as to manipulate it, but as synthesizer, providing the basis for a metareligious vision and enabling us to see ‘the integral majesty of the natural world’ and the wonder of the universe (pp. 95,98). This underpins the creative future he sees for humankind.

There is a wide appreciation in Christian traditions of our need to be better stewards. A number of Diocesan documents and resources are available to inspire liturgy and help towards action. The Environment Working Group of the General Synod is compiling liturgical and theological resource lists for ready access, and will be facilitating the sharing of action plans. Some examples of evangelical contributions are ‘Environment – A Christian Response’ and ‘Christian Ministry in a Changing Climate – Report to Synod’ (both at http://www.sie.org.au/tag/environment and awaiting an update) and the Declaration on Creation Stewardship and Climate Change from the Micah Network, July 2009.

However, to change mindset and act accordingly is an enormous challenge. On 13 December 2009 during the Copenhagen conference on climate change the Archbishop of Canterbury preached on casting out fear and acting for the sake of love (5). He said that ‘we cannot show the right kind of love for our fellow-humans unless we also work at keeping the earth as a place that is a secure home for all people for future generations.’ ‘We are faced with the consequences of generations of failure to love the earth as we should.’ ‘We are not doomed to carry on in a downward spiral of the greedy, addictive, loveless behaviour that has helped to bring us to this point. Yet it seems that fear still rules our hearts and imaginations. We have not yet been able to embrace the cost of the decisions we know we must make. We are afraid because we don’t know how we can survive without the comforts of our existing lifestyle. We are afraid that new policies will be unpopular with the national electorate. We are afraid that younger and more vigorous economies will take advantage of us – or we are afraid that older, historically dominant economies will use the excuse of ecological responsibility to deny us our right to proper and just development.’ The Archbishop ended by emphasizing that love casts out fear and with a plea not to be afraid, but to ask how we show that we love God’s creation, and how we learn to trust one another in a world of limited resources through justice and caring for our neighbour.

Moving directly to the topic of this paper, the theologian John Painter was invited to address the Commission in June 2008 to provide a theological vision that might stimulate and assist it to develop its work agenda. The paper he presented, ‘An Anglican approach to Public Affairs in a Global context’, has now been re-shaped for publication (6). In it he recognises that we are inextricably part of one world, and that human activity in one place affects life in every place. Earth is the fragile web of life of which we, and all life, are part. The narrative of the creation in Genesis contains within it an affirmation of the intrinsic worth of the creation as a whole and of its component parts; Psalms such as 24, 95 and 104 celebrate the value of the Earth and its parts; and the Prologue of the Gospel of John sets both the creation of the world and the incarnation of the Word in the context of God’s love for the world. The paper expresses the need for us to hear the call for justice for the Earth and all its creatures, and to celebrate the marvels and mysteries of creation and of the loving Creator whose bounties we enjoy, while also ensuring that all of Earth’s creatures share in this bounty.

With the burgeoning human population now posing a threat to all life on the planet, Professor Painter considers there is a need to develop ‘a more adequate theology of sexuality’. (He observes that churches and religious groups generally have not given a constructive lead on the issue of human population growth, and confesses that he can see no solution to the threat to all life if this growth is not checked. In his view, while human sexuality will continue to find expression in a deep and abiding human love as a basis of community or family, and procreation and the birth of children in the context of a loving relationship remain very important, these need to be within limits that allow other species to flourish. He concludes that only then will there be a rich and diverse Earth for our children and our children’s children to live on.)

Given all these expressions, it is very sobering to realize that the United Nations projects another 2.4 billion people to be living on the Earth by about 2050 (1). As yet there is no agreement on enough action to safeguard the wellbeing of the Earth, and the current rates of extinction of life forms are comparable with the five great extinctions of the distant past, the last being 65 million years ago when the dinosaurs disappeared.

2. Why is it so difficult to discuss population issues? Some reasons and responses

Population is an emotive and controversial topic. It has been virtually a taboo subject, the ‘elephant in the room’. Reasons why people prefer to be silent about it include:

. Many benefit from population growth in the short term – businesses sell more products and make more profit, builders build and sell more homes, but demand still outstrips housing supply and anyone who owns a home benefits because the value of the home increases.

- However those who do not own their own homes, particularly young people and the poorer members of our community, will find it increasingly difficult to achieve ownership. This is a serious social justice issue.

.Population growth readily translates to economic growth, which is a prime goal of governments.

-However, economic growth for a nation does not necessarily mean growth in individual incomes. Over the past seven financial years, real GDP has grown by 23% but real GDP per person has grown by less than half that (7). Questions need to be asked – Who really are the beneficiaries of economic growth once a certain (and not particularly high) level of personal/family financial security has been achieved? Should ongoing economic growth be an end in itself - and increase in population used as a means to achieve it? Does the community as a whole benefit from it? Are there alternative economic paradigms?

.Some consider that a bigger population makes Australia more secure and gives the nation more international influence, though it may not be diplomatically attractive to express such motivation. These kinds of considerations will have contributed to the increase in the immigration rate, and also to the introduction by the previous Government of a Baby Bonus, which has been continued and even increased by the current Government.

-There are good counter examples of nations with significantly smaller populations who contribute strongly to civilization and carry much international influence (8, p. 117 ).

. Some consider that an increased birth rate is a necessary means of helping to compensate for the ageing of population which is now taking place in Australia. The introduction of the Baby Bonus may well be an outcome of such thinking. One of the world’s leading thinkers and activists in economic development, Jeffrey Sachs, addresses this concern which is basically that the social security systems of the rich world will collapse as more retirees live longer and have fewer workers to support them. He points out that in the high-income world the ratio of those older than 65 to those aged 15 to 65, called the old-age dependency ratio, will increase from 23% to 46% by 2050, and that this will indeed impose stresses on pension systems, but ‘it is simply not true that the costs are likely to be large’. First, with slower population growth or even decline, there will be large social savings in major infrastructure investment that was previously needed to keep up with population; second, retirement ages are likely to rise gradually by a few years, particularly as older people enjoy more healthy life years; and continued improvements in productivity may well mean we can work less in total, some of the returns being taken as greater leisure time (9, pp. 200-202).

- In the context of unsustainable global population growth it is inconsistent and arguably irresponsible to provide financial incentives for population increase.

. Some business leaders seek substantial skilled immigration to provide a good selection of potential employees with skills needed for their companies. Governments may also find this an attractive way to overcome shortfalls in essential services personnel such as health workers.

- The far more constructive alternative is to plan ahead and train current citizens in the fields that are needed, so improving total employment prospects for existing Australians and also the opportunities for more skilled and satisfying work. Risks associated with oversupply in the job market include unemployment of both skilled and unskilled people, with personal trauma and unproductive costs to the national budget. There is also a need to be concerned about depriving less developed countries, from which many skilled migrants come, of people who are needed in their home countries.

. Some consider that the basic problem is consumption, and growth in consumption, not population growth.

- Consumption does indeed need to be restrained, but that cannot take the pressure off population as a key underlying issue. With global population growth continuing at a very significant rate, reductions in consumption per person in developed countries (with total population about 1.2 billion out of 6.8 billion globally) are unlikely to be sufficient to achieve reduced global consumption as population, incomes and consumption per person rise in rapidly developing countries with their much higher populations. The total impact on the environment arises from average consumption per person multiplied by total number of people. Both consumption and population need to be addressed, and very sensitively, given the benefits received by rich nations from their use of global resources.

. Many Australians have migrated here and they do not feel it is fair to ‘pull up the drawbridge’ when others want to come.

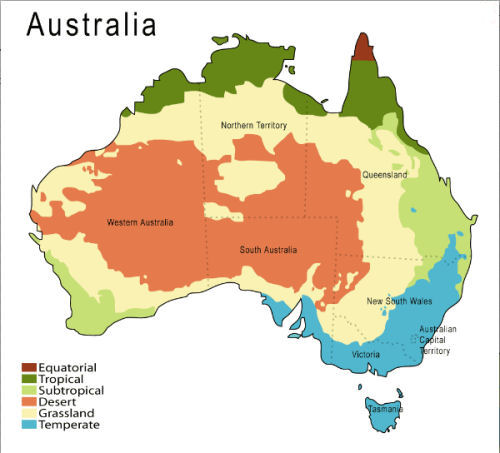

-In response, it is not expected that Australia would want or need to close off immigration. Our country has been greatly enriched by migrants over a long period, and we are a successful multicultural society. There is scope to increase our intake of genuine refugees (which is very small compared with total immigration – see next section) and continue to enable family reunion, while decreasing total immigration to a level consistent with scientific advice on the long term carrying capacity and preservation of the biodiversity of the Australian continent.

. Australia has obligations to other nations, particularly island nations, who will be adversely affected by climate change.

- True. However, it is also true that Australia will be one of the nations affected most severely by climate change and that some of the island nations have high population growth which will be unsustainable on their land area regardless of climate change. This is part of the global population picture and, in addition to accepting refugees, we need to support such countries in restraining their population growth to achieve balance with their countries’ natural resources.

. Immigration is a topic on which some extreme views have been expressed in Australia in the past, and people are very afraid of being perceived as selfish, racist or xenophobic; some extend this to express the view that, although they recognize the overarching significance of population growth, the church should not speak about population for fear of being misinterpreted.

- If fear prevents us from speaking the truth for the greater good, out of love for the whole earth including all our fellow human beings, are we being true to our faith? Again, the words of the Archbishop of Canterbury encourage us not to be afraid, but to ask how we show that we love God’s creation, and how we learn to trust one another in a world of limited resources through justice and caring for our neighbour (5). Justice and care take many forms.

- Crispin Hull writes ‘Very few people who oppose higher population and high immigration want a Hansonite revival. Indeed, many would happily see more refugees and much lower general immigration. But we do want to see some sense and some moral purpose in Australia’s population policy’ (9).

. Birth control education and facilities are sensitive for some church members because they disagree with the extent of services offered, in Australia and overseas, especially in developing countries with large family sizes and burgeoning populations.

- Balancing such matters can be very hard, but the big picture is of overpopulation. Isn’t it important to support those seeking to enable women and men to choose family size - those who, through voluntary means, are trying to achieve the greatest good – for the individual woman, for the wellbeing of all her children, for her nation and for the world as a whole - through education and reproductive health services including contraceptives - as advocated by Sachs (9, Chapter 8).

. Some church members wish to avoid discomfort in relation to colleagues of other denominations or faiths, whom they expect to reject birth control measures, and they do not want to cause tension on this account.

- The big picture is of over-population and the need to care for the future of all life on earth. Love needs to drive out fear so that those who recognise the population problem speak out about it, in love. The responses of some of our colleagues may surprise. Some of them, too, may be fearing to acknowledge publicly what they recognize in their hearts.

3. Where to from here?

Briefly, the facts:

. The resources of the Earth are being used unsustainably

. Global human population is huge and still increasing rapidly

. Human activity is the root cause of current environmental stress and climate change; these threaten

- the survival of poorer people, and

- major extinctions of other life forms by the end of this century.

The fundamental problem:

. Global population growth is unsustainable. On a finite planet, if the rate is not reduced rapidly, there will be huge problems for humanity and other life forms.

This paper offers a brief overview of issues and some responses, globally and for Australia.

3.1 The broad costs of overpopulation

Many of the costs of overpopulation are not directly concerned with money, but involve changes in society and its interaction with the natural world. These and a wide range of other issues are discussed by O’Connor and Lines (8), and they have been addressed in the special series of ABC TV 7.30 Reports centering around Australia Day 2010 (25 – 29 January 2010, accessible on the internet, ref.10). The growing congestion of cities, destined to become worse, means much time lost in commuting, more polluted suburbs, denser housing and the loss for many of suburban gardens in which to relax and still have some frequent communion with nature – which in turn means children and future citizens are likely to have less empathy with the natural world. Other consequences include the build-up and crowding of Australia’s narrow and beautiful coastal strip, with destruction of most of its natural forest adjacent to beaches, and the forgoing of good arable land because it is being built upon. Water supply is already a major challenge for many parts of Australia and it will become an even greater challenge as climate change intensifies and population increases; restrictions apply now in nearly all major population centres as well as agricultural areas. The public in general do not want these kinds of negative changes to their quality of life. Polls have also shown that the majority of people do not want large immigration programs. O’Connor and Lines put the view that minimizing individual consumption is a poor answer if population is not stabilised. They say that if citizens save water, for example, it will not mean that their neighbours get more water for their gardens, or that tougher restrictions will be postponed. Rather it will enable the population to be increased, and even lead eventually to worse shortages of water and other environmental disasters (8, p.182). A challenging thought.

3.2 Global population issues

The human population grew from about 230 million when Christ was born (9, p.60, 64) to 6.8 billion now. Factors such as better living conditions, nutrition and health care have ensured steadily improving life expectancy. According to the United Nations’ most recent revision of World Population Prospects (2006, ref. 1), total global population is projected to reach 9.2 billion before there is likelihood of overall stabilization and then decline. The medium variant projected increase from now to 2050 is approximately equivalent to the size of the world population in 1950 (1).

The UN Report confirms the diversity of demographic dynamics among the different world regions. The population of the more developed regions is expected to remain largely unchanged at 1.2 billion, and this population is ageing, while virtually all population growth is occurring in the less developed regions and especially in the group of the 50 least developed countries, many of which are expected to age only moderately over the foreseeable future. There are distinct trends in fertility and mortality underlying these varied patterns of growth and changes in age structure. Below-replacement fertility prevails in the more developed regions and is expected to continue to 2050. Fertility is still high in most of the least developed countries and although it is expected to decline it will remain higher than the rest of the world. In the rest of the developing countries, fertility has declined markedly since the late 1960s and is expected to reach below-replacement levels by 2050 in the majority of them.

Realisation of the medium variant projections contained in the UN 2006 Revision Report depends urgently on ensuring that fertility continues to decline in developing countries. These projections assume that in the less developed countries as a whole, fertility will decrease from 2.75 to 2.05 children per woman from 2005-2010 to 2045-2050; and in the 50 least developed countries, from 4.63 to 2.50 children per woman. The UN states (1 , p.6) that to achieve such reductions it is essential that access to family planning expands in the poorest countries of the world; otherwise, if fertility were to remain constant at the levels estimated for 2000-2005, the population of the less developed regions would increase to 10.6 billion (instead of the 7.9 billion projected by assuming that fertility declines). World population would then rise to 11.8 billion. That would mean world population increasing by twice as many people as were alive in 1950.

There is no certainty of well-managed decline unless significant change in human behaviour takes place. The ‘green revolution’ initiated some decades ago may have kept pace with increased human need for food so far, but there are serious doubts that the peak number of people could be fed by means of more increases in production (11). An October 2009 report under the auspices of the Royal Society says that many and major changes would be required if this were to be achieved (12). Agricultural productivity currently depends on fertilizers based on fossil fuels, there are severe limitations on increases in agricultural land and water for crops and increases come at the expense of other forms of life. Up to 50% of the Earth’s photosynthetic potential is directly appropriated for human use, and land that is being cleared now is either increasingly inhospitable or home to precious and unique stocks of biodiversity, such as tropical rainforests (9, p. 68). We are approaching the limits of what science can realistically achieve, and the technologies needed now may well be as much the social technologies of policy and administration in adapting to limitations as they are about technologies of production itself (11).

A wide range of issues relevant to this paper are addressed by Jeffrey Sachs in his book ‘Common Wealth – Economics for a Crowded Planet’ (9). Basic observations are that the scale of human economic activity has risen eight times since 1950, will rise possibly another six times by 2050, and is causing environmental destruction on a scale that was impossible at any earlier stage of human history (9, p.29). Scientists have estimated that if habitat conversion and other destructive human activities continue at their present rates (which is hard to avoid if population keeps increasing, poor people in the poorest countries struggle to survive, and standard of living increases in newly industrialising nations), half the species on Earth could be extinct or unsaveable by the end of this century (2, pp.4-5 and Chapter 8). And we are causing this in the face of evidence that a decline of biological diversity may render many parts of the world less hospitable, less resilient and less productive for human beings as well (9, p.29).

In response Sachs names three basic goals: environmental sustainability, population stabilization, and ending extreme poverty. These are the essence of the Millenium Development Goals (9, p.32). Here we concentrate on what he has to say about population stabilization (which is strongly linked to the other two goals).

. He notes the ‘tyranny of the present’ when it comes to population growth. For example, impoverished parents often have many children to ensure their old age security or perhaps in the hope of obtaining more communal land or other resources, but this may well come at the expense of the children’s own wellbeing – the parents cannot provide effectively for the nutritional, health and educational needs of six or seven children, a not uncommon family size (9, p.41). A household’s decision on fertility also depends on widespread cultural norms, the availability of education and contraceptive means through public health facilities, and other matters determined by public policy. Decentralised decision-making of individual households can easily lead to excessive population growth. Sachs argues that the rapid growth of populations in poor countries (commonly a doubling in a generation) hinders their economic development, condemns the children to continued poverty and threatens global political stability (9, Chapter 7).

. Global population dynamics are complex (9, Chapter 7, pp 159-182). There is nothing automatic about a transition to lower fertility following a decline in child mortality and, when it does occur, the total fertility rate declines with a lag leading to a population bulge before a low fertility/low mortality stage can be reached. Governments have played a key role in the rapid decline of child mortality, and they have also had to step in, or need to, to promote a rapid decline in fertility to accompany the decline in mortality.

. He gives four compelling reasons why the poorest countries need to speed up the demographic transition and why we need to help them do it: families cannot surmount extreme poverty without a decline in the fertility rate; neither can poor countries; the ecological and closely related income consequences of rapid population growth are devastating; and finally there are threats to the rest of the world, raising pressure for mass migration, and increasing risks of local conflict, violence and war (9, pp.175-6).

. There is hope. Public policies designed to promote a voluntary reduction of fertility rates can have ‘an enormous effect’, benefiting both present and future generations. Sachs names nine factors that have proved time and again to be important in leading to a rapid decline in fertility rates, while noting that not all are needed: improving child survival, education of girls, empowerment of women, access to reproductive health services, green revolution, urbanization, legal abortion, old age security, and public leadership. His basic advice is that development policy for a high fertility region should integrate aid for economic development with aid for family planning (9, p.184).

. Nevertheless, it has been difficult to obtain support from rich countries to help poor countries speed up their demographic transition. Sachs outlines (9, p177 – 182) the way in which support and results have waxed and waned with political change. Intergovernmental conferences on population and development were held in 1974, 1984 and 1994, and the multidimensional plan of action from the last of these forms one of the most important Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The UN Millennium Project’s special report on sexual and reproductive health (2006) came up with an estimate of the scale of donor effort needed to ensure broad coverage of contraception and family planning, also safe childbirth, and it was approximately 0.06% of the income of the donor countries. But the financial goals have not yet been met. Contributing much more to this cause would be a very effective and compassionate way for Australia to help people in poor nations, and their environments.

3.3 Australian population issues

The book ‘Overloading Australia’ provides a wealth of information, insight and references (8).

In Australia, for people who have currently lived their three score years and ten, there were approximately:

- 4.4 million people when their parents were born (1910)

- 7.0 million when they were born (1940)

- 12.5 million when their children were born (1970)

- 19.2 million when their grandchildren were born (2000)

(ABS, Australian Historical Population Statistics Catalogue 3105.0.65.001). There are more than 22 million now, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics population clock. That growth has kept accelerating. Our population growth rate in percentage terms is the highest in the developed world (2.1% for the year to June 2009, ABS, Australian Demographic Statistics, Catalogue 3101.0), and is now at a level typical of developing countries. It is higher than growth rates in eg Indonesia, China and India. We in Australia are part of the global overpopulation issue.

In 2008 when the Australian population exceeded 21 million there was no significant public comment or policy discussion. A startling official projection for increase in Australia’s population, to 35 million people in the next four decades, was publicised in September 2009 prior to the formal release of the 2010 Intergenerational Report of the Department of the Treasury (13). This was significantly higher than the previous official projection from 2007, only two years previously; and Dr Ken Henry, Secretary of the Treasury, expressed personal pessimism on 22 October 2009 (at a Business Leaders’ Forum at the Queensland University of Technology) about Australia’s capacity to be able to deal with environmental sustainability while housing and absorbing this big population. Meanwhile the Prime Minister, on the ABC 7.30 Report of 22 October 2009, said initially that he thought it was good news that Australia’s population is growing – good for national security long term and for what Australia can sustain as a nation; recently he has been more cautious, having acknowledged that the demands for coping with substantial increases will be ‘massive’. The current Opposition Leader has been quoted as saying that he would like to see as many people are possible given the chance to live in Australia (14).

The composition of Australia’s population increase is food for thought. In the most recent year for which the full data are available on the ABS web site (2007-2008, ABS Catalogue 3412.0 released 28 July 2009):

the population grew by 1.71% or 359,300 people, to reach a total of 21.431 million (note that this rate increased to 2.1% in the year to June 2009, Cat. 3101.0)

net overseas migration added about 213,700 (and this is excluding people on student and work visas, many of whom become eligible to stay), while

natural increase added 145,600 per year (births minus deaths).

It was the third year in which net overseas migration had exceeded natural increase. The numbers carry major implications for the growth of the Australian population well into the future. While rapid growth is being encouraged by key political leaders, expressions of concern are now coming from a serving politician, the Federal MP for Wills, Kelvin Thomson, who has put forward a 14 point plan for population reform (15), and the Federal MP for Menzies, Kevin Andrews, who has called for a national discussion about population, noting that planning, infrastructure, transport, health, education etc share population as a critical element (16). Concern has been expressed for many years from the scientific community (eg 17, 18, which both indicate the Australian population is already around the level of what can be sustained), some public figures such as the former Australian of the Year Tim Flannery (19, 20), former Premier of NSW Bob Carr (21) , and from bodies such as Sustainable Population Australia and the Australian Conservation Foundation (22). But until very recently the discussion did not appear to have traction. This has changed following the Treasury’s 2010 Intergenerational Report projection of 36 million by 2050 and a debate is now taking place. Population projection is not simple and the projection of 35 or 36 million has been queried as inconsistent with underlying facts and hence too low (23). Furthermore, what happens after 2050 also needs to be in mind, because there would be momentum to continue growing.

The question must be asked whether our current and projected population growth is fair to future generations of Australians and to other life in the environments our descendants will have to inhabit. This does not imply a lack of concern for those in need in other countries – on the contrary. Compared with total immigration, humanitarian migration into Australia has been very small – about 14,000 per year, but of these only about 4000 to 6000 were refugees by the United Nations’ definition (8, p.73). There is scope for Australia to respond more generously in humanitarian immigration, and it is likely to become necessary as population around the world continues to increase. Looking at the global situation of political, ethnic, religious and environmental refugees, numbers can be expected to increase and the manifold causes often include or centre around population pressure (ibid., p.74).

The Public Affairs Commission is of the view that the risks are too high to allow the numbers to run away in Australia without very serious consideration of the risks and the alternatives. In this very thirsty and thin-soiled continent there is a need for a national debate on Australia’s population, leading to a population policy consistent with the big picture for national and global environment and population, while supporting those in need. The debate has recently become lively and there have been many comments from knowledgeable people about the serious issues Australia must address if the nation is to absorb a major increase in population, including water shortages, land shortages, higher food and housing costs, stressed infrastructure in cities, degraded rivers (eg 10, the ABC 7.30 Report special series, 25 – 29 January 2009, archived and available on line).

It is not the role of this paper to prescribe population policy in detail. That is a responsibility for elected politicians, taking account of factors such as congestion, infrastructure and amenity, expert advice on Australia’s environmentally sustainable carrying capacity, and views in the electorate. We ask that our Government fulfil the responsibility to determine sustainable population policy and ensure that there would be no significant increases in environmental and social stress from any major increase.

Reflecting the debate, a responsible course would include:

. taking full account of Australia’s role in contributing to the global overpopulation/overconsumption problem, with its implications for greenhouse gas emissions and devastation of the global environment;

. reduction in total immigration rates while increasing the proportion of refugees and family reunion migrants in the total and

. removal of public incentives aimed at increasing the birth rate and replacing them with support for improvements in the capacity of parents to be fully attentive to their babies, eg by increasing paid maternal and paternal leave.

In addressing population policy, the following values are important to us:

Justice, not only for current Australians, but for our descendants and the other life on this land in all its beauty and diversity

Care for those in need and for the broadest wellbeing of human and other life, and

Sharing in a world of finite resources, building trust by showing justice and care (and love!) for our neighbours in other parts of the world.

4. To speak or not, from a Christian’s viewpoint

Remaining silent about population issues, although one has concerns about them, is little different from supporting further overpopulation and ecological degradation. If people are not prepared to speak up, these things will happen. Given the high risks from global and national population growth, can any of the above reasons justify saying nothing while numbers continue to climb? Out of care for the whole Creation, particularly the poorest of humanity and the life forms who cannot speak for themselves, this paper argues that it is not responsible to stand by and remain silent.

It is, however, a challenge to participate in the debate. People with vested interests, who may not see the whole picture, can put forward plausible partial views. None of us particularly want to give up things we like, or expose ourselves to dismissive or angry reactions. This paper can only try to emphasise the big picture. It is sometimes difficult to keep the whole picture in view – but there is danger that a partial view, adopted for reasons that appeal in the short term, can lead to avoidance of long term responsibility.

5. What can we do?

We can each act individually, but to have an impact on the fundamental issue of population growth it is essential that governments establish sustainable population policy. Based on the big picture, it is hoped that this paper will encourage people to communicate to our Government their concerns about global and national population growth. We owe it to the whole Creation, including our own descendants. There is no time to lose.

Reinforcing recommendations from the March 2009 PAC discussion paper, we need as individuals to

. Grow in understanding of global and national environmental challenges, become acutely aware of the issues, and address them as a whole, with integrity.

. Be prepared to make personal and corporate sacrifices for the common good of all Creation: Change our own ways individually and collectively to reduce our own consumption, helped by others including Diocesan Environment Commissions and Registries.

But beyond that we need to communicate big picture population concerns to our Governments, asking them to

. Recognise the fundamental role of burgeoning population growth and related human consumption in causing unsustainable environmental stress globally and in Australia

Determine a sustainable population policy for Australia, which is fair and just for current and future Australians and for other life on this land and aims for the broad wellbeing of all

. Halt any policy that provides an incentive specifically and primarily to increase Australia’s population, notably the Baby Bonus, while increasing paid maternal and paternal leave ; and reduce the overall level of immigration to fit with expert advice on the sustainable capacity of this land, while being more generous in our programs for refugees and family reunion.

. Effectively and compassionately improve the welfare of people in poor nations, and hence their environments, by contributing much more to restraining global population growth through voluntary means, via appropriate international channels including those of the United Nations. For high fertility regions, aid for family planning needs to be integrated with aid for development.

. Reject any assumption, clearly untenable in the longer term, that there has to be ongoing population growth in order to maintain economic growth as a prerequisite for human wellbeing.

**********

References (in addition to those in the March 2009 Public Affairs Commission paper referred to in the attachment)

1. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, ‘World Population Prospects – the 2006 Revision’, http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/wpp2006/English.pdf

2. Wilson, Edward O, The Creation – An Appeal To Save Life On Earth, W W Norton & Co, New York and London, 2006, 175 pages.

3. Williams, Rowan (Archbishop of Canterbury), ‘The Climate Crisis: Fashioning a Christian Response’, Lecture at Southwark Cathedral sponsored by the Christian environment group Operation Noah, 13 October 2009 (http://www.archbishopofcanterbury.org/2565)

4. Berry, Thomas, The Dream of the Earth, Sierra Club Books, San Francisco, 1988, 247 pages.

5. Williams, Rowan (Archbishop of Canterbury), ‘Act for the sake of Love’, Sermon in Copenhagen Cathedral, 13 December 2009 ( http://www.archbishopofcanterbury.org/2673)

6. Painter, John, ‘An Anglican Approach to Public Affairs in a Global Context’, to be published in St Mark’s Review, 2010 (2) No. 211.

7. Gittins, Ross, ‘Let’s think twice about growth by immigration’, Economics Editor, Sydney Morning Herald, 28 September 2009.

8. Mark O’Connor and William J Lines, Overloading Australia, published by Envirobook, Canterbury NSW 2008, and second edition 2010, 241pages.

9. Sachs, Jeffrey D, Common Wealth – Economics for a Crowded Planet, Penguin Books printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives, 2009, 386 pages.

10. ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation), The 7.30 Report, special series of programs 25 – 29 January 2010, http://www.abc.net.au/7.30/archives/2010/730_201001.htm

11. Stewart, Jenny, ‘Limit to what science can do’, The Canberra Times, 26 October 2009.

12. Royal Society, London, ‘Reaping the Benefits: Science and the sustainable intensification of global agriculture’ October 2009, 86pages, http://royalsociety.org/Reapingthebenefits/

13. Department of the Treasury, Intergenerational Report 2010, http://www.apo.org.au/research/intergenerational-report-2010

14. Hull, Crispin, ‘Watch this space of ours, or we may just populate and perish’, The Canberra Times, Forum p.19, 30 January 2010.

15. Thomson, Kelvin, Federal Member for Wills, ‘There is an alternative to runaway population – Kelvin Thomson’s 14 Point Plan for population Reform’, 11 November 2009, http://www.kelvinthomson.com.au/speeches.php

16. Thomson, Kevin, Federal Member for Menzies, ‘How many people do we need’, presentation to the Australian Environment Foundation Conference, Canberra 20 October 2009, http://aefweb.info/data/Kevin%20Andrews%20presentation.doc

17. Australian Academy of Science and authors, Population 2040 Australia’s Choice, published by the Australian Academy of Science, Canberra, 1995, 144 pages.

18. Ten Commitments – Reshaping the Lucky Country’s Environment, Editors David Lindenmayer, Stephen Dovers, Molly Harriss Olson and Steve Morton, CSIRO Publishing, 2008, 237 pages.

19. Flannery, Tim, ‘Now or Never – A sustainable future for Australia’, Quarterly Essay Issue 31, 2008, pp.1-66.

20. Flannery, Tim, ‘Beautiful Lies – Population and Development in Australia’, Quarterly Essay Issue 9, 2003, pp. 1-73.

21. Carr, Bob, ‘Perish the thought that we can handle a bigger population’, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age, 19 November 2009.

22. Australian Conservation Foundation, ‘Population and Demographic Change’, http://www.acfonline.org.au/articles/news.asp?news_id=2110

23. Hull, Crispin, ‘Population projection not so simple’, The Canberra Times 6 October 2009.

*********

Attachment

Responses to Global and National Environmental Stresses *

The facts

. The resources of the Earth are being used unsustainably – fossil fuels will run out, land cannot be cleared indefinitely for agriculture, fresh water used on the crops to feed more people cannot be drunk or available to other life

. Global population has increased from about 300 million when Christ was born to more than 6.8 billion now, and is still rising rapidly; Australia’s own population has increased three-fold in the last 70 years, and continues to increase rapidly

. Consumption is increasing with population

. Consumption (directly or indirectly) causes environmental stresses and increases greenhouse gas concentrations

. Greenhouse gas increases cause climate change

. Increased human activity is the root cause of environmental stress/climate change

. Environmental stress and climate change threaten

the welfare and even survival of poorer people

major extinctions of other life forms by the end of this century

. We have already passed the ‘tipping point’ of greenhouse gas concentrations for serious climate change, and with concentrations continuing to rise, the Earth is approaching a ‘point of no return’, which cannot be predicted accurately, from which no action we take would be able to avert catastrophe.

The fundamental cause

Global population growth is unsustainable.

Australia’s rate of population growth is one of the highest in the developed world.

What responsibility do we bear?

Resolutions from the Lambeth Conference 1998 reaffirm the Biblical vision of Creation as a ‘web of inter-dependent relationships bound together in the Covenant which God has established with the whole earth and every living being’. They state that ‘humans beings are both co-partners with the rest of Creation and living bridges between heaven and earth, with responsibility to make personal and corporate sacrifices for the common good of all Creation’. The conference recognized that ‘unless human beings take responsibility for caring for the earth, the consequences will be catastrophic’.

What can we do?

It is within the power of each of us to do the following:

change our own ways substantially and quickly to lessen our impact as individuals and as the church, using the Diocesan resources prepared by the Environment Commission and the Registry, educating ourselves also in other ways about reducing our consumption, and encouraging each other to action along the way support conservation of life forms and ecosystems in our own environment and work for environmental causes that do so nationally and internationally, and become acutely aware and talk to others, in our parishes and in the wider community, about the kinds of issues addressed in the Public Affairs Commission paper.*

And importantly we can, as individuals and collectively, encourage our Government(s) to:

Apply integrated thinking to environmental issues, recognizing that pressures linked to increases in population are the fundamental cause of them.

Place economic policy firmly in the overall framework of environmental management and well-being, not the other way around, and recognize that population policy is necessary to achieving balance.

Set policy with incentives and regulations that will rapidly achieve much greater environmental sensitivity and efficiency in the use of energy, water and land for agriculture.

Give very high priority to fostering large scale use of technologies that will enable major greenhouse gas emission reductions.

Reject the assumption that there has to be population growth in order to maintain economic growth as a pre-requisite for human wellbeing.

Do the utmost towards cutting greenhouse gas emissions by 90% by 2050 and 25% below 2000 levels by 2020 (a fair share for Australia of a global target of 450 parts per million carbon dioxide equivalents, which might for example enable the three-dimensional structure of the Great Barrier Reef to survive)

And internationally:

Play a leading role with increased funding to protect the hottest spots of biodiversity in the world, ensuring that this investment improves long term living standards of people who would otherwise find it necessary to convert more habitat and thus destroy more of the other life forms with which we share the Earth

Work vigorously at the climate summit in Copenhagen in December 2009 for agreement on global and national targets that will avert global catastrophe

Contribute further to restraining global population growth through the UN Fund for Population Activities and other appropriate international channels.

Australia’s share of distressed people needs to be welcomed warmly, but the main focus needs to be on aid for improvements in other countries. There is a powerful case for a substantial increase in aid by our Government and by individuals in Australia. Education broadly underpins human wellbeing and continues to deserve strong support, but there is a special case now for an aid focus that enables conservation of biodiversity at the same time as it enables people to achieve appropriate and sustainable living standards.

* This brochure is based on a paper released early in 2009 by the Public Affairs Commission of the Anglican General Synod, for discussion within the Church and the wider community. The full paper with references and bibliography is accessible on the General Synod web site at http://www.anglican.org.au/governance.cfm?SID=2

CANON NO. 11, 2007

PROTECTION OF THE ENVIRONMENT CANON 2007

A Canon to assist in the protection of the environment

The General Synod prescribes as follows:

Preamble

A. This Church acknowledges God’s sovereignty over his creation through the Lord

Jesus Christ.

B. In Genesis it says that “The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of

Eden to till it and keep it.” In 1990 the Anglican Consultative Council gave modern

form to this task when it declared that one of the five marks of the mission of the

Church was "to strive to safeguard the integrity of creation, and to sustain and renew

the life of the earth”.

C. This Canon gives form to this mark of mission in the life of the Anglican Church of

Australia.

D. This Church recognises the importance of the place of creation in the history of

salvation.

E. This Church acknowledges the custodianship of the indigenous peoples of this land .

F. This Church recognizes that climate change is a most serious threat to the lives of the

present and future generations. Accordingly, this Canon seeks to reduce the release

of greenhouse gases by this Church and its agencies.

Short title and principal canon

1. This Canon may be cited as the “Protection of the Environment Canon 2007”.

Mechanisms to assist in protecti ng the environment

2. (1) Every diocese which adopts this Canon undertakes to reduce its

environmental footprint by increasing the water and energy efficiency of its

current facilities and operations and by ensuring that environmental

sustainability is an essential consideration in the development of any new

facilities and operations, with a view to ensuring that the diocese minimalises

its contribution to the mean global surface temperature rise .

(2) Every diocese which adopts this Canon undertakes to est ablish such

procedures and process such as an environment commission, or similar body

as are necessary to assist the diocese and its agencies to:

(a) give leadership to the Church and its people in the way in which they

can care for the environment,

(b) use the resources of God’s creation appropriately and to consider and

act responsibly about the effect of human activity on God’s creation,

(c) facilitate and encourage the education of Church members and others

about the need to care for the environment, use the resources of God’s

creation properly and act responsibly about the effect of human activity

on God’s creation, and,

(d) advise and update the diocese on the targets needed to meet the

commitment made in sub-section (1);

(e) urge its people to pray in regard to these matters.

Reporting

3. (1) Every diocese which adopts this Canon undertakes to report to each ordinary

session of the General Synod as to its progress in reducing its environmental

footprint in order to reach the undertaking made in acco rdance with subsection

(1) of section 2.

(2) Any report will outline the targets that were set, the achievements made, and

difficulties encountered.

Adoption of Canon by Diocese

4. The provisions of this Canon affect the order and good government of the C hurch

within a diocese and the Canon shall not come into force in any diocese unless and

until the diocese by ordinance adopts the Canon.

On Ockham's Razor on ABC Australia, today, 30 October 2011, hundreds of thousands of people would have heard 24 year old Fiona Heinrichs blast the mainstream media's failure to provide a voice for the younger generation and its promotion of of an ideology of unending growth. Fiona also delivered a blistering critique of Bernard Salt's unscientific promotion of population growth and his failure to respond to her challenge to debate him, which was recently the subject of an article on OnLineOpinion. This is the text of the talk. You can also download the podcast here.

On Ockham's Razor on ABC Australia, today, 30 October 2011, hundreds of thousands of people would have heard 24 year old Fiona Heinrichs blast the mainstream media's failure to provide a voice for the younger generation and its promotion of of an ideology of unending growth. Fiona also delivered a blistering critique of Bernard Salt's unscientific promotion of population growth and his failure to respond to her challenge to debate him, which was recently the subject of an article on OnLineOpinion. This is the text of the talk. You can also download the podcast here. On Ockham's Razor on ABC Australia, today, 30 October 2011, hundreds of thousands of people would have heard 24 year old Fiona Heinrichs blast the mainstream media's failure to provide a voice for the younger generation and its promotion of of an ideology of unending growth. Fiona also delivered a blistering critique of Bernard Salt's unscientific promotion of population growth and his failure to respond to her challenge to debate him, which was recently the subject of an article on OnLineOpinion. This is the text of the talk. You can also download the podcast here.(This introduction by Sheila Newman)

On Ockham's Razor on ABC Australia, today, 30 October 2011, hundreds of thousands of people would have heard 24 year old Fiona Heinrichs blast the mainstream media's failure to provide a voice for the younger generation and its promotion of of an ideology of unending growth. Fiona also delivered a blistering critique of Bernard Salt's unscientific promotion of population growth and his failure to respond to her challenge to debate him, which was recently the subject of an article on OnLineOpinion. This is the text of the talk. You can also download the podcast here.(This introduction by Sheila Newman)

According to WWF UK and most other environmental organisations like Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth, it is demand from wealthy nations that is the real problem and the world’s unsustainable population growth is not a fundamental concern, merely something to ignore, because it is an ‘inconvenient truth’.

According to WWF UK and most other environmental organisations like Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth, it is demand from wealthy nations that is the real problem and the world’s unsustainable population growth is not a fundamental concern, merely something to ignore, because it is an ‘inconvenient truth’.

"Despite this grim picture, unlike global population growth, our own population future is very much under our control and we need not be overwhelmed. Stability of population numbers is within our reach this century. We owe it to Victorians who will be born 50 years from now to take control so that those who come after us can enjoy what we have enjoyed – clean air and water and reliable food and housing supplies. To do nothing is the real crime against humanity." Jill Quirk, President, Sustainable Population Australia (SPA) Victoria.

"Despite this grim picture, unlike global population growth, our own population future is very much under our control and we need not be overwhelmed. Stability of population numbers is within our reach this century. We owe it to Victorians who will be born 50 years from now to take control so that those who come after us can enjoy what we have enjoyed – clean air and water and reliable food and housing supplies. To do nothing is the real crime against humanity." Jill Quirk, President, Sustainable Population Australia (SPA) Victoria.

Film and text of speech now available inside article. Speech given at Planning Backlash Forum of 7 Nov 2010: "In July last year I made a 22 page submission to the Victorian Government titled “5 Million is too many: Securing the Social and Environmental Future of Melbourne”. So given that I think 5 million would be too many, you can imagine what I think of the idea of doubling Melbourne’s population to 8 million. Melbourne’s population is growing on a scale not seen in Australia before, swelling by almost 150,000 people in the last two years. Melbourne’s population is growing by more than 200 people per day, 1500 per week, 75,000 per year. This is much faster than all other major Australian cities. It will give us another million people in 15 years."

Film and text of speech now available inside article. Speech given at Planning Backlash Forum of 7 Nov 2010: "In July last year I made a 22 page submission to the Victorian Government titled “5 Million is too many: Securing the Social and Environmental Future of Melbourne”. So given that I think 5 million would be too many, you can imagine what I think of the idea of doubling Melbourne’s population to 8 million. Melbourne’s population is growing on a scale not seen in Australia before, swelling by almost 150,000 people in the last two years. Melbourne’s population is growing by more than 200 people per day, 1500 per week, 75,000 per year. This is much faster than all other major Australian cities. It will give us another million people in 15 years."

There is an unrelenting media campaign to tell Canadians that we must grow our population. We need more babies and more immigrants or very bad things will happen. But there are voices that question this assumption. They are heard on the streets, in the pubs and at the dining room table. But they are seldom heard in the media. Especially not on the airways of the CBC, that vehicle of growthist PC propaganda which all taxpayers are forced to endow.

There is an unrelenting media campaign to tell Canadians that we must grow our population. We need more babies and more immigrants or very bad things will happen. But there are voices that question this assumption. They are heard on the streets, in the pubs and at the dining room table. But they are seldom heard in the media. Especially not on the airways of the CBC, that vehicle of growthist PC propaganda which all taxpayers are forced to endow.  "The growth lobbyists will tell us that we can solve our problems by converting to “clean coal” technologies or nuclear power, building more high rise, producing desalinated water at $10 litre (who knows?), installing “smart” electricity meters, piping water from the Northern Victoria to Melbourne, importing more food on more and bigger ships etc." Federal Candidate, Jenny Warfe writes, "I'm looking forward to a different way of 'moving forward.'"

"The growth lobbyists will tell us that we can solve our problems by converting to “clean coal” technologies or nuclear power, building more high rise, producing desalinated water at $10 litre (who knows?), installing “smart” electricity meters, piping water from the Northern Victoria to Melbourne, importing more food on more and bigger ships etc." Federal Candidate, Jenny Warfe writes, "I'm looking forward to a different way of 'moving forward.'"

Quark writes about how the mainstream press is becoming increasingly hysterical in its promotion of growth lobby propaganda, particularly since the Australian Federal election in August 2010.

Quark writes about how the mainstream press is becoming increasingly hysterical in its promotion of growth lobby propaganda, particularly since the Australian Federal election in August 2010. Population sociologist Sheila Newman's talk, "Stable Population dynamic demystified," presented fascinating original material using social and biological research showing how most animals, including humans, can maintain steady state populations in different environments and conditions. Whilst showing how small populations can be maintained, it failed to bear out Hobbs' dismal prognostications.

Population sociologist Sheila Newman's talk, "Stable Population dynamic demystified," presented fascinating original material using social and biological research showing how most animals, including humans, can maintain steady state populations in different environments and conditions. Whilst showing how small populations can be maintained, it failed to bear out Hobbs' dismal prognostications.

On Monday 17 May I interviewed William Bourke about himself and his party and his views on the politics of the current population debate. He described concerns about the impact of population numbers since the 1990s, but said that reading the book,

On Monday 17 May I interviewed William Bourke about himself and his party and his views on the politics of the current population debate. He described concerns about the impact of population numbers since the 1990s, but said that reading the book,

Recent comments