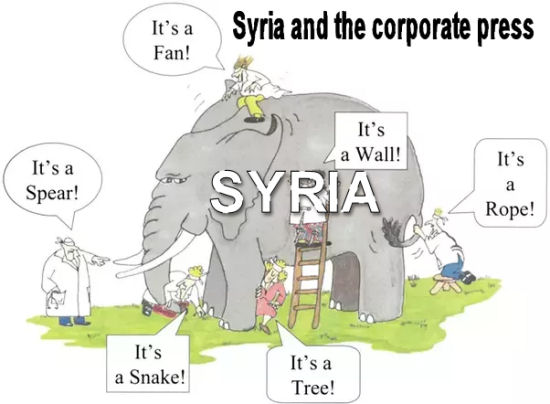

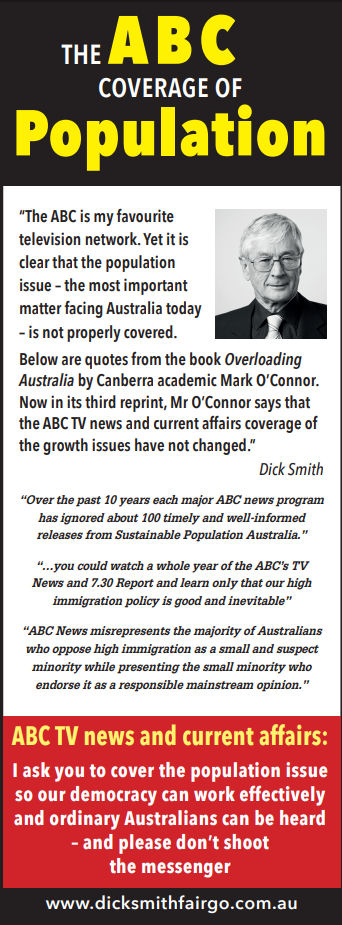

Growth lobbyists outnumbered environment and democracy proponents three to two on Last Monday's Q and A on ABC 1, with Jane Fitzgerald (Property Council of Australia), Jonathan Daley (Grattan Institute) and Dr Jay Song (Immigration professional who arrived here two years ago) and Tony Jones (Compere) vs Tim Flannery (Population scientist and author of the famous Future Eaters) and Bob Carr, (journalist, environmentalist, and former Premier of New South Wales). The show started with a brilliant question from audience member, Matthew Bryan. He read it off his mobile phone, with a steely emotional intensity that only someone blinded by dollar values could have ignored, and all the growthists did, of course. Nonetheless since the ABC almost never invites representatives of the non-growth side, we could call this an improvement. Read on for a commentary on some of the highlights and lowlights of this historic confrontation between truth and lies and ignorance.

Growth lobbyists outnumbered environment and democracy proponents three to two on Last Monday's Q and A on ABC 1, with Jane Fitzgerald (Property Council of Australia), Jonathan Daley (Grattan Institute) and Dr Jay Song (Immigration professional who arrived here two years ago) and Tony Jones (Compere) vs Tim Flannery (Population scientist and author of the famous Future Eaters) and Bob Carr, (journalist, environmentalist, and former Premier of New South Wales). The show started with a brilliant question from audience member, Matthew Bryan. He read it off his mobile phone, with a steely emotional intensity that only someone blinded by dollar values could have ignored, and all the growthists did, of course. Nonetheless since the ABC almost never invites representatives of the non-growth side, we could call this an improvement. Read on for a commentary on some of the highlights and lowlights of this historic confrontation between truth and lies and ignorance.

Most egregious in argument technique and substance was Dr Jay Song, described as an 'Immigration Expert'. Property Council of Australia's Jane Fitzgerald seemed to know enough to underplay the almost absolute power of the Property Council of Australia, which is on the way to running and ruining this country. Grattan Institute representative Jonathan Daley urbanely projected a dispassionate acceptance of growth as a given, and significant expertise in growth cliches.

Tim Flannery waved his hand like a man drowning at sea, yet often failed to get the attention of the moderator who seemed unaccountably fascinated by Dr Jay Song.

Water and the NBN

Flannery's suggestions for democratic decisions and common sense about Australia's vital resource poverty may have been overly sophisticated for the growthists and the commentator, who seemed unaware of the fact that we are 30% desert, 30% rangeland and only 4% truly fertile land. On the other hand, maybe they understand, but just didn't want to discuss anything real. Tony Jones actually implied that lack of water could be overcome by the rolling out of the NBN. Will we ever know if he was joking or serious?

TIM FLANNERY

Look, the history of Australia has been really telling in that regard because we have seen a relative shrinkage of many of those inland cities. And I think the reason is that the resource base is just so limited. So, even the agricultural resource base in many of those areas, even our rich irrigation areas, is really small compared with the resource base over much of North America or Europe or East Asia. There’s just...it’s really hard to marshal enough resources – even with education as being one of those things – and mass to break through. And, yet, in Melbourne and Sydney, we’re part of a global community, really. A lot of our wealth comes from that international trade. Once you get into real Australia, outside that, the...

TONY JONES

Well, if the NBN is in those places, anyone can do anything, can’t they?

(LAUGHTER)

The Aging population furphy

Bob Car similarly, despite performing like an agile intellectual seal in his home element, about to nail his position to perfection, had whole sentences clipped off, with Tony Jones abruptly seeking Miss Song's opinion, which came out like a word-salad, bearing no relationship to the question. Is Dr Song a professional filibusterer? She has a long, diverse, academic record, so, although Australian university standards are plummeting, it seems to me that, either they have collapsed completely or her job on the panel was expressly to confuse.

BOB CARR

Yeah, that’s the argument about the ageing of the population. The truth is, the age profile of the migrant intake ain’t that much different from that of your existing population. As one demographer said, you would have to run immigration at very high levels – higher than we’ve got now – and for a very long time to make a significant difference to a factor that’s touching every country in the world.

TONY JONES

Bob, I’m not sure that everyone in this panel will agree with that point. I’m just going to go to Jay Song.

BOB CARR

Let me just... Let me just...

TONY JONES

I just want to pick you up on that point first.

BOB CARR

Just another sentence.

TONY JONES

I’ll come back to you.

(LAUGHTER)

BOB CARR

OK. I’ll hold you to that.

TONY JONES

Alright, I’ll come back to you. But is that correct? I mean, looking at the migration intake, I would have thought it skews young.

Dr JAY SONG

I mean, Australia has done a fantastic policy on migration management. I mean, it’s a very well-designed policy and also a well-managed one, ‘cause it’s targeting the skills and the qualifications they have, and then they choose very carefully who can contribute, who can come here and contribute to the economy. Not just the economy, but also the social capital they’re bringing from their home towns, and also the connection they are making between Australia and the country of origin they are originally coming from.

And these migrants are chosen... First of all, you need to have skills and qualifications in the degrees or other technical capabilities. Second of all, you need to pass the character test. So there is no security concern, national security concern. They are not a threat to national security. Third of all, they have to be healthy...and employable, and they also come here and pay huge tax. And the average income among these skilled migrants is actually $5,000 more than the average Australian taxpayer. And lastly, they also make efforts to be integrated into Australian society, because they value the same democracy, equal opportunity, and also the concern for environmental protection and, yeah, diversity.

It was somewhat disappointing that Bob Carr, who so expertly conveyed his message and argued his position, only advocated a political solution of halving the immigration program.

BOB CARR: Do we really want to be adding 1 million to our population every 3.5 years? Would it be such a departure from God’s eternal plan for this continent if we took six years about acquiring an extra million?

In light of the absolute democratic breakdown and planning and environment chaos that came though clearly, it made more sense to argue for zero net.

The whole thing started with a brilliant question from audience member, Matthew Bryan. He read it off his mobile phone, with a steely emotional intensity that only someone blinded by dollar values could have ignored, and all the growthists did, of course. Meanwhile, for many watching their screens, he was a hero, as he conveyed their message to those who have declared war on Australia, using bulldozers instead of guns.

Do the growthists understand how angry we are?

MATTHEW BRYAN

MATTHEW BRYAN

We’ve seen a sharp decline in our living standards in the past five to 10 years. Unaffordable housing, overdevelopment, low wage growth, increase in traffic congestion and pollution, and overcrowded schools, hospitals and public transport are now part of life in Sydney and Melbourne, and our other cities will soon be the same. Australians aren’t stupid. They realise that the root cause is our rapid population growth driven by the highest immigration rate in the developed world, currently at over 200,000 per year, and that the main advocates of this unsustainable immigration are corporate and political elites who love being able to boost their profits and brag about GDP growth via an ever-increasing consumer base. Do you think our politicians understand how angry Australians are about our mass immigration program?

In response, Bob Carr appropriately cited the TAPRI "poll that shows 74% of Australians think there is enough of us already."

Jane Fitzgerald, Property Council of Australia, managed to make it sound as if the effects of immigration-induced rapid population growth were not related to immigration, suggesting that "Australians welcome migration, generally," but said she hoped that our political leaders were listening. Yes, they are listening - to the Property Council of Australia.

JANE FITZGERALD

I don’t know, Tony, if people are angry about migration, or if they’re angry because it takes a long time to get around the city and the transport... Getting around the city – a city like Sydney or Melbourne – is tough. I think Australians welcome migration, generally. Now, I’m not talking about population increases, necessarily, in that context, but I don’t know if the anger is about migration. I do hope – I do hope – that our political leaders are listening, though, and I understand the frustration, as I said, if you’re struggling to get around your city...

Tim Flannery reflected the many years he has been debating and writing about Australia's undemocratic and unmanagable rate of population growth and the promises that have never been fulfilled.

TIM FLANNERY, CHIEF COUNCILLOR, CLIMATE COUNCIL

Look, Matthew, the problems you pointed to are not new problems. I have lived through government after government that’s promised to fix them with decentralisation, or new projects, or whatever – transport projects. It’s never happened, and I don’t think it will happen because the costs involved to keep up with this very rapid growth are large indeed.

Now, you asked, you know, “Are politicians...? Do they understand how angry people are?” There’s an underlying issue there, which is about, why has this problem occurred? And it’s because politicians, with very few exceptions, such as Bob, none of them want a smaller constituency. None of our church leaders want a smaller congregation. None of our businesses want to sell fewer things. So, unless we, the people, speak up on this, and are heard, and control the agenda, special interest groups will see population growth continue.

Jones then zoomed over to Jay Song who went onto seemingly automatic pilot in a ramble of cliches about what immigrants bring to Australia, and emphasizing the high quality of these immigrants as ensured by strict testing, with an additional plus being that they earn more than Australians!

She then added irrelevant and hard to substantiate claims that immigrants value democracy, equal opportunity, environmental protection [which is poor and deteriorating in Australia as it sacrifices habitat for people] lastly adding "yeah, diversity," presumably referring to human cultural linguistic , religious, racial, rather than ecological. She threw in the "You can't stop them coming," argument, which Tim Flannery would later answer and which would be Bob Carr's last word. She also sounded very much as if she was attempting to summon up Pauline Hanson as a strawman responsible for [74% of Australians being jack of the immigration tsunami]: "I think there is some responsibility, some part on the politicians’ side. I think they’re creating some fearmongering and finger-pointing – the migrant as a problem." Fortunately she did not get away with it.

Dr JAY SONG, MIGRATION POLICY EXPERT

Yeah, Matthew, I mean, I understand your concerns. I’m not sure whether Australians are angry about the incoming migration. Like myself, I’m one of those recent immigrants. I came to Australia two years ago as a temporary 457 skilled migration, um, skilled migrant. But then I work with Australians. I respect the Australian values. It’s a mature democracy. I respect diversity, multiculturalism. The working environment is fantastic, so I decided to apply for permanent residency, and then I’ve got it six months ago. And I really appreciate, first of all, to be on this show as a migrant – a recent migrant – and I feel very fortunate and privileged to be on this show to contribute my thoughts and opinions and my expertise to the population debate, which is a very important conversation that Australia, as well as migrants, are all having.

Um, while population is growing – that’s the trend in the world – we can’t stop that from happening. It is something happening not just in Australia, but worldwide. We can’t stop people from coming. I understand the pressure on the infrastructure. I understand that there is a congestion issue, there is a housing affordability issue, and also the pressure on schools and hospitals. But I think the question is not about the number of migrants. When you look at the data, 60% of those permanent migrants are actually skilled migrants who are contributing to the economy and society and the diversity in the community. 30% of those permanent migration are family migrants, who are also contributing to building the families and strengthening the families. Only less than 10% of those permanent migration are humanitarian migrants.

I think there is some responsibility, some part on the politicians’ side. I think they’re creating some fearmongering and finger-pointing – the migrant as a problem. But I think, what we all, as Australian, also recent immigrants, permanent residents, we altogether... What Australians want is also what migrants want too. We don’t want the congested, you know, heavy traffic when we go to work. We also respect the clean environment, a sustainable environment, and we all want to grow together as a nation.

Bob Carr and Tony Jones vie for the last word

Here is Bob Carr's last word:

BOB CARR

If you say the test of our migrant policy is our obligation to the world, our moral obligation to the world that that is how we’ll run immigration, there’d be no limit. We’d certainly be saying we would take a million people a year.

Our obligation to the world is best expressed by us managing sustainably this vast and remarkable and beautiful continent we’ve got and making ourselves so prosperous that through our overseas development assistance program, we can be regarded as the most generous of the world’s wealthy countries. And not least by running an aid program with the most important feature in it being funding of family planning. Because that is the contribution that can make the most decisive difference in elevating a country out of the misery of mass poverty and on to the trajectory of becoming a middle-income nation.

But it was drawn out a little by Tony Jones:

TONY JONES

I don’t want quite want to end on a prophylactic effect. So, let me just ask a political question to you.

BOB CARR

You can’t run a program about population and not run that risk.

And Tony then tried to tar Bob Carr with the unfortunateTony Abbott brush, but Carr is a lot smarter than Tony:

TONY JONES

Just before we go out, Tony Abbott – and you seem to be on the same page with him on this – made the same case you are making, halving the migration policy, a couple of weeks ago. His Cabinet colleagues all jumped on him and silenced him quickly. What do you think is going on?

BOB CARR

You’re asking me to analyse Tony Abbott’s motivation in this?

TONY JONES

No, no, only since you agree with him on the migration?

BOB CARR

Well, he agrees with me.

(LAUGHTER)

BOB CARR

I’ve been saying this longer than him. Look, Tony, I rest my case with this proposition – we can achieve all the decent effects we want for ourselves and for others by running an immigration program just markedly less ambitious than it’s been, giving us time to recover, to get things right. Don’t shrug it off and say, “It’s all a matter of planning, it’s all a matter of infrastructure.” That’s too easy. That’s an easy way out. Let’s get it right by giving ourselves a bit of planning space, by just seeing that the level comes down appreciably. That’s the position that 74% of Australians have reached. And I think, on this, they’re absolutely right.

Full transcript below

TONY JONES

Good evening, and welcome to Q&A. I’m Tony Jones. Tonight’s Four Corners examined Australia’s booming population, but now we’d like to take that conversation further. To help us do that, nearly one-third of our audience tonight come from two critical areas of Western Sydney, both at the coalface of rapid development – Parramatta, which is destined to be Sydney’s second CBD, and Camden and Wilton, the sites of massive new housing developments.

Here to answer your questions, the head of the Climate Council, Tim Flannery, the CEO of the Grattan Institute, John Daley, migration policy expert from the University of Melbourne, Dr Jay Song, the executive director of the New South Wales Property Council, Jane Fitzgerald, and former foreign minister and New South Wales premier Bob Carr. Please welcome our panel.

(APPLAUSE)

TONY JONES

Thank you very much. Our first question tonight comes from Matthew Bryan.

MASS MIGRATION ANGER

MATTHEW BRYAN

We’ve seen a sharp decline in our living standards in the past five to 10 years. Unaffordable housing, overdevelopment, low wage growth, increase in traffic congestion and pollution, and overcrowded schools, hospitals and public transport are now part of life in Sydney and Melbourne, and our other cities will soon be the same. Australians aren’t stupid. They realise that the root cause is our rapid population growth driven by the highest immigration rate in the developed world, currently at over 200,000 per year, and that the main advocates of this unsustainable immigration are corporate and political elites who love being able to boost their profits and brag about GDP growth via an ever-increasing consumer base. Do you think our politicians understand how angry Australians are about our mass immigration program?

TONY JONES

Let’s start with one of the former political elites, Bob Carr.

BOB CARR, FORMER NSW PREMIER

Well, I’m interested that the first poll I’ve seen that indicates a big shift in public attitudes on this came out in recent months. It shows 74% of Australians think there is enough of us already, and as someone who’s been talking on ecological and economic grounds for less immigration rather than more, I find that interesting. It’s the first breakthrough.

And I think politicians and business leaders ought to be acknowledging that it has finally sunk in. I thought I was a lonely voice for a long time, but I think in recent... I would say in the last 12 months, the message has sunk in, and the key message is this – immigration is good.

We are a migrant nation. Our character derives from the fact that so many of us were born overseas. But would it be such a tragedy if, instead of adding 1 million to our population every 3.5 years, we took six years about it? Could we achieve the benefits of immigration with a more manageable annual intake?

TONY JONES

So, Bob, just to interrupt for a moment. Well, former political elite, that is former prime minister Tony Abbott, recently came out and asked for the migration intake to be cut in half. It sounds like you’re on song with him. Is that what you’re saying?

BOB CARR

Yeah, more or less. I would leave it to the experts to work out and to address the different categories. But I think... I think the majority of Australians, especially those who live in the big, stressed cities – Sydney and Melbourne receive 90% of the migrant intake – would be saying, “Just give us a bit more to absorb the increase.” Immigration is our character. 37% of the population of Sydney was born overseas. We’re proud of it. We celebrate it. But even those people – those born overseas – are still asking whether we can achieve the same benefits at a less dramatic pace.

It is the highest in the world. It is the highest in the world. Do we really want to be adding 1 million to our population every 3.5 years? Would it be such... Would it be such a departure from God’s eternal plan for this continent if we took six years about acquiring an extra million?

TONY JONES

Jane Fitzgerald?

JANE FITZGERALD, PROPERTY COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA, NSW

I think the reality of the situation is that Australia has always grown. Every Commonwealth government, including the one that Bob was part of, has set this country on a trajectory for growth. Whether that growth is 0.6% or 1%, if we don’t plan for growth, we won’t solve the problems that are currently out there. So, I think we need to think about how we can do this collaboratively and constructively.

We need to think about how we learn the lessons of the past 20 years, where we’ve grown by 6 million already. And for all of the struggles that we face in a city like Sydney, or a city like Melbourne, they’re undoubtedly better cities than they were 20 years ago. Now, I’m not saying that that’s... it’s not a challenge catching the train that’s crowded. I do that every morning myself. But if we plan for and we deliver infrastructure in the way that we can confidently, then we will be OK. And if we believe that we’re not going to grow, we will only repeat the problems of the past 20 years.

TONY JONES

Jane, I’ll quickly bring you to the question that was asked there. Do you think our politicians understand how angry Australians are about our mass migration program? That was the question. Do you think there is anger out there? Do you think politicians get it, if that’s true?

JANE FITZGERALD

I don’t know, Tony, if people are angry about migration, or if they’re angry because it takes a long time to get around the city and the transport... Getting around the city – a city like Sydney or Melbourne – is tough. I think Australians welcome migration, generally. Now, I’m not talking about population increases, necessarily, in that context, but I don’t know if the anger is about migration. I do hope – I do hope – that our political leaders are listening, though, and I understand the frustration, as I said, if you’re struggling to get around your city...

TONY JONES

Jane, we’ll come to some specific questions on those issues in a minute. I’ll just pass around to the panel. Tim Flannery?

TIM FLANNERY, CHIEF COUNCILLOR, CLIMATE COUNCIL

Look, Matthew, the problems you pointed to are not new problems. I have lived through government after government that’s promised to fix them with decentralisation, or new projects, or whatever – transport projects. It’s never happened, and I don’t think it will happen because the costs involved to keep up with this very rapid growth are large indeed.

Now, you asked, you know, “Are politicians...? Do they understand how angry people are?” There’s an underlying issue there, which is about, why has this problem occurred? And it’s because politicians, with very few exceptions, such as Bob, none of them want a smaller constituency. None of our church leaders want a smaller congregation. None of our businesses want to sell fewer things. So, unless we, the people, speak up on this, and are heard, and control the agenda, special interest groups will see population growth continue.

TONY JONES

Jay Song?

Dr JAY SONG, MIGRATION POLICY EXPERT

Yeah, Matthew, I mean, I understand your concerns. I’m not sure whether Australians are angry about the incoming migration. Like myself, I’m one of those recent immigrants. I came to Australia two years ago as a temporary 457 skilled migration, um, skilled migrant. But then I work with Australians. I respect the Australian values. It’s a mature democracy. I respect diversity, multiculturalism. The working environment is fantastic, so I decided to apply for permanent residency, and then I’ve got it six months ago. And I really appreciate, first of all, to be on this show as a migrant – a recent migrant – and I feel very fortunate and privileged to be on this show to contribute my thoughts and opinions and my expertise to the population debate, which is a very important conversation that Australia, as well as migrants, are all having.

Um, while population is growing – that’s the trend in the world – we can’t stop that from happening. It is something happening not just in Australia, but worldwide. We can’t stop people from coming. I understand the pressure on the infrastructure. I understand that there is a congestion issue, there is a housing affordability issue, and also the pressure on schools and hospitals. But I think the question is not about the number of migrants. When you look at the data, 60% of those permanent migrants are actually skilled migrants who are contributing to the economy and society and the diversity in the community. 30% of those permanent migration are family migrants, who are also contributing to building the families and strengthening the families. Only less than 10% of those permanent migration are humanitarian migrants.

I think there is some responsibility, some part on the politicians’ side. I think they’re creating some fearmongering and finger-pointing – the migrant as a problem. But I think, what we all, as Australian, also recent immigrants, permanent residents, we altogether... What Australians want is also what migrants want too. We don’t want the congested, you know, heavy traffic when we go to work. We also respect the clean environment, a sustainable environment, and we all want to grow together as a nation.

TONY JONES

Jay, I’m going to interrupt there because we’re going to come to a lot of those issues as we go along. John Daley? And keep it reasonably tight, if you can.

JOHN DALEY, CEO, GRATTAN INSTITUTE

So, Matthew, I think, if you look at the numbers, it suggests that people are not putting migration as the top worries. But they are, for example, now citing housing affordability as the thing that they are second most concerned about, just after health. They’re clearly very concerned about congestion in traffic.

So, all of those things are, at least in part, the consequence of migration, but they are also the consequence of government policy on what we’ve done about planning or haven’t, what we’ve done about transport or haven’t. And so I think what people are reacting to is the effects. And I think what it does is that it illustrates that the key issue here is, in part, what number do we want for migration? But it’s also, and just as importantly, what policies do we put in place to deal with that growth? And if we’re not going to get those policies in place, how do we adjust migration given that?

TONY JONES

Very briefly, you’re talking about anger really generated by poor planning?

JOHN DALEY

Well, I think anger by the consequences of poor planning, which is that, essentially, houses are, and apartments are, much more expensive than they should be.

TONY JONES

OK. Let’s move to our next question from John McGregor. Go ahead.

MIGRATION/POP GROWTH

JOHN McGREGOR

Thank you. For some people, the perception is that strong population growth means strong economic growth, and therefore a big Australia is a strong Australia. The fears some people have is that any nation that decides to stabilise or even reduce its population is risking its economic resilience and vitality. My question is to those on the panel advocating population limits – how do you respond to the fears of those Australians who have concerns that their economic security is threatened by any move to stabilise or reduce Australia’s population?

TONY JONES

OK, Bob Carr, back to you.

BOB CARR

Well, I don’t know whether that is the accurate description of Australian public opinion. As I said, the poll shows that 74% of Australians think we don’t need more people. So, I’m... I mean, that’s where we... that’s where we’re starting with. We’re starting with a public concern about the notion that going on increasing our population every year and doing so at the most ambitious level of any developed country in the world is the right path forward.

But Australia’s going to have a secure and prosperous future, even if we were to run immigration at roughly half the level it is now. The markets of Asia are opening up for us. Whatever Trump does on protection, we’ve got free trade agreements with the nations that are producing the world’s biggest middle class. In South-East Asia, there will be a billion new middle-class consumers. In this era, having a big domestic market has got no advantage in the way it did for us back in the 1950s or the 1970s. The world is our market, and a smart, highly-educated, highly-skilled people – yes, a small population, in world terms – can be world-beaters given these conditions.

TONY JONES

Bob, your own former colleague, Lindsay Tanner, once the finance minister, says that Australia will struggle to pay for health, education, and all of the things that we’ve come to expect in this country without a larger population to help pay for it, especially with the huge ageing burden that we have.

BOB CARR

Yeah, that’s the argument about the ageing of the population. The truth is, the age profile of the migrant intake ain’t that much different from that of your existing population. As one demographer said, you would have to run immigration at very high levels – higher than we’ve got now – and for a very long time to make a significant difference to a factor that’s touching every country in the world.

TONY JONES

Bob, I’m not sure that everyone in this panel will agree with that point. I’m just going to go to Jay Song.

BOB CARR

Let me just... Let me just...

TONY JONES

I just want to pick you up on that point first.

BOB CARR

Just another sentence.

TONY JONES

I’ll come back to you.

(LAUGHTER)

BOB CARR

OK. I’ll hold you to that.

TONY JONES

Alright, I’ll come back to you. But is that correct? I mean, looking at the migration intake, I would have thought it skews young.

Dr JAY SONG

I mean, Australia has done a fantastic policy on migration management. I mean, it’s a very well-designed policy and also a well-managed one, ‘cause it’s targeting the skills and the qualifications they have, and then they choose very carefully who can contribute, who can come here and contribute to the economy. Not just the economy, but also the social capital they’re bringing from their home towns, and also the connection they are making between Australia and the country of origin they are originally coming from.

And these migrants are chosen... First of all, you need to have skills and qualifications in the degrees or other technical capabilities. Second of all, you need to pass the character test. So there is no security concern, national security concern. They are not a threat to national security. Third of all, they have to be healthy...and employable, and they also come here and pay huge tax. And the average income among these skilled migrants is actually $5,000 more than the average Australian taxpayer. And lastly, they also make efforts to be integrated into Australian society, because they value the same democracy, equal opportunity, and also the concern for environmental protection and, yeah, diversity.

JOHN DALEY

Tony, if I can add to that, we’ve actually had a big shift in our migration policy over the last decade. So, if you go back before about 2006, many of the migrants who came were older, and the age profile relative to the age profile of the population was not that different. But if you look at the last 10 years in particular, we have seen a substantial increase in the number of migrants, and they have been skewed very young. So, the vast majority have been under the age of 45. And that’s a big shift in...

TONY JONES

OK, let’s leave that point there so I can go back to Bob, because that’s... You said they were skewed old, and I believed the figures say they’re skewed young. So I just want to pick you up on that point. I think we’ve heard from John Daley that what you said was not correct.

BOB CARR

Yeah. No, the overall pattern is that migration can produce an age profile in the intake not that different from the existing population. So, you’ve got some relief in recent years, but before that, with dependents, and other considerations, it wasn’t that different. And the conclusion would be that if we... We simply can’t...

TONY JONES

He’s talking about the past 10 years...

BOB CARR

Yes, if I can put it this way...

TONY JONES

..in which we got six million more people.

BOB CARR

We can’t avoid the ageing of the population. No country in the world is going to avoid it. But just notice what has happened since 2000. People have adjusted their working lives and you’ve had a 2% increase in the participation in the workforce of people in their 60s and 70s. These matters are capable of resolving themselves without this weird experiment Australia is currently conducting in having an immigration intake greater than any other advanced country in the world, with a population growth that resembles that of a Third World country, of a developing country. This is peculiar. It’s unique to Australia. It’s producing enormous stress, especially in our two biggest cities, or our three biggest cities, and there are alternatives. In fact...

TONY JONES

Bob, I’m going to ask you to just pause some of your thoughts there...

BOB CARR

Sure.

TONY JONES

..because you’ll get a chance to answer more of that. And, Tim Flannery, the questioner actually put it to those who would rather see a smaller population, and you’re certainly one of those.

TIM FLANNERY

Well, John was asking about defence and comparative issues around security, national security, and, you know, Australia is going to be a small nation by Asian standards. I mean, you know, Indonesia, our nearest neighbour, will always be multiple times bigger than us. We have to cope with that sort of world. But it’s also important to realise that global population growth is slowing, yeah? And by the second half of the century, we hope it’ll be stabilised.

So, the whole world is going to be in this boat, of dealing with ageing, of dealing with all of the issues that come about with this. And I don’t see it as something exceptional for us. You know, the big questions for us, really, are what do we, as Australians, want? How big a population do we want? You know, how are we going to satisfy our security needs, given that we’ll always be small?

Dr JAY SONG

I agree with him. I mean, it’s not about the number or the rate of immigration. But I think what we really need to have as a discussion today is how we want to grow as a nation together.

TONY JONES

But the interesting thing is, we haven’t had that debate.

Dr JAY SONG

Exactly.

TONY JONES

Quite a long time ago, we had a debate, and now we find the population is going to be much, much bigger than we thought, but we haven’t had a debate. That’s why we’re here tonight, and actually we’ve got a lot of people in the audience who are at the cutting-edge of this debate. Let’s go to one of those now. Sue Johnson.

TRANSPORT BEFORE DEVELOPMENT

SUE JOHNSON

Thank you. If great urban design and sustainability comes from high-density living near railways with viable... Sorry, near transport with viable and reliable options for transport, and close proximity to employment and key services, what risks are there in applying population growth and high density into the peri-urban areas of metropolitan... of the greater metropolitan areas such as the Blue Mountains and Wollondilly? I’m asking this question in the context of the Wilton Priority Precinct, which aims to build a new city of 50,000 people with no access to public transport.

TONY JONES

Jane Fitzgerald, no access to public transport, yet we’re going to build an extra 50,000 people into this community. How does that work and how does that happen? How is it allowed to happen?

JANE FITZGERALD

Tony, I think the issues that Sue is raising are really important ones and I think the bottom line is we’ve got some choices here. Infrastructure Australia put out a report a couple of weeks ago, a week or so before John did with the Grattan report that came out, about how we want Sydney to grow in particular – do we want to keep sprawling, do we want to have more high density around railway lines and the type of things that you’re talking about, or do we want to try and share the load more equitably across the city.

I think the answer is that we need to share the growth across the city as much... as equitably as we possibly can. I think in areas like yours, there is some good news relating to things like the Western Sydney City Deal which was announced only last Sunday week, where, for the first time, Sue, what you’ve actually got are eight local governments, the state government, and the Commonwealth government – and I hasten to add, a bipartisan policy position at both Commonwealth and state level – where they’ve agreed to work together to try and plan that part of Western Sydney better than they have in the past. So, what that means...

TONY JONES

Can I just ask a question? Why do all the houses get built before the public transport is put in place?

(LAUGHTER)

TONY JONES

It’s pretty obvious...

JANE FITZGERALD

It’s a great question.

It’s a great question.

TONY JONES

Should there be rules to stop that from happening?

JANE FITZGERALD

Absolutely.

TONY JONES

I mean, you’re with the property developers.

JANE FITZGERALD

Absolutely. There should be rules.

TONY JONES

You’re talking on their behalf. So, shouldn’t they just say, “We’re not going to build there until you put a rail line”?

JANE FITZGERALD

It’s absolutely a no-brainer, and you’d think that we would have done it before now, but we haven’t done it that way in the past, and that’s all there is to it.

BOB CARR

It happens precisely when you run immigration at double the rate it ought to be run, because the infrastructure, the infrastructure struggles to keep up. And what government pours into infrastructure is adequate to cope with an existing population, but struggles to cope with the needs when it’s the highest rate of immigration in the developed world.

TONY JONES

But, Bob, I’m going to have to say this. You were premier for 10 years, ‘95 to 2005. Why didn’t you build a world-class railway system out to all these suburbs?

BOB CARR

Let me answer that question. Let me answer that question.

TONY JONES

A lot of people would like to hear the answer.

BOB CARR

Let me answer that question. I’m proud of the fact that according to a treasury assessment I received last week – because I asked a former head of state treasury to give it to me – that during my time as premier we increased capital work spending by the whole of government in the 10 years I was premier by a total of 40%. Now, that’s in real terms. And enabled some huge projects. And I will simply tweet to Q&A a list of them now so they go up and everyone can have access to them. It would have been impossible for any premier, not just this one, during 10 years to have increased capital works outlay by above 40% in real terms.

TONY JONES

Unless you were looking into the future. Because we’re always going to grow very fast.

BOB CARR

We were running at a pretty bold level, Tony. And we were criticised in the media not for spending too little, but we were criticised in the media because we were the last of the big spenders.

TONY JONES

Alright. Sorry about the retrospective critique. We’re going to move on to the present. Back to Jane.

BOB CARR

Can I just make a point to Jane?

TONY JONES

Quickly.

BOB CARR

That when you’re running immigration this high, no matter what the intentions of government, and its boldness in committing money to infrastructure, you will struggle to keep up. That is a fact of life.

TONY JONES

OK, Jane.

JANE FITZGERALD

Sue, I think the difference now, apart from the fact that you’ve actually got all levels of government, which I’m sure wasn’t the case, Bob, back then. I’m sure that there wasn’t a compact between the federal government, the state government, eight local government areas, to work together to make sure that the infrastructure goes in there first. What you need out there in Western Sydney under the City Deal is you need, I think, 1,300 classrooms, you need about 200,000 jobs. All of these things are built in to the City Deal.

TONY JONES

Jane, can I just pause you there? Because Sue had her hand up. We’ll go back to her question.

SUE JOHNSON

I just wanted to ask Jane how far does she think $15 million from the City Deal will take us in solving the problem.

JANE FITZGERALD

I think, Sue, that you’ve got to acknowledge that in New South Wales at the moment there’s about $80 billion being spent on road and rail infrastructure. There’s always a challenge, there is a catch-up that we’re doing at the moment. Regardless of what Bob says, we’re having to catch up in some parts of the city in relation to rail and infrastructure. But if we keep planning forward-looking... We have bodies now like Infrastructure Australia, that I mentioned before.

BOB CARR

Yeah, but, Jane, a very quick comment. Since 2011 there hasn’t been in New South Wales a single new transport project opened. There hasn’t been the cutting of a ribbon on a single one.

TONY JONES

OK, Bob, I’m going to pause you because we want to hear from the other the panellists, and we also want to hear from other questioners. And we’ve got a question from Camden. Another one of those cutting-edge areas. Bill Parker.

OUR ROADS ARE MESSED UP

BILL PARKER

Thanks, Tony. I have lived in the Camden area for about 20 years, and I’ve noticed a recurring pattern with traffic congestion. So, it gets to the point where it’s intolerable, the existing roads are widened. Six to 12 months later, they’re clogged up again. And then the pattern repeats every few years. People spend more time commuting, and there’s no integration out there. I know there’s no plan.

Our politicians now tell us regularly that there are budget constraints and we hear more about what we can’t do and what we can’t get. So, my question is, what will it take for our leaders to show vision to give our young nation a world-class integrated suburban transport network that will enrich our economies, our society, our quality of life, and still meet the future needs of urban sprawl?

TONY JONES

I’m going to start on this side of the panel. John Daley.

JOHN DALEY

Well, unfortunately, it’s going to take our politicians to have a lot more courage, because, so far, the way they’ve mainly tried to deal with that problem is by building more stuff. And, as you say, almost inevitably, when we build a new road, it pretty quickly gets congested. Now, if you go to a place that has a lot of people living in a very small area, but with very little congestion, you go to Singapore. Why is there so little congestion in Singapore? Well, partly, they’ve got more restrictions on buying a car, but largely because they essentially charge you to drive on the road, and they charge you a lot more to drive on the road when everybody else wants to drive on the road.

What’s known as road pricing. Now, it’s not wildly popular, would be a fair summary. The idea that we should pay, and particularly pay more, to go on our roads when we drive at peak hour is something that intuitively most people are a bit suspicious about. But the evidence is overwhelming that if you’re serious about actually trying to reduce congestion, that’s the kind of thing that works.

TONY JONES

But, John, it only works if you’ve got a first-class transport system. There’s no point stopping people driving their cars if there’s no other way to get to the city.

JOHN DALEY

But I would suggest, you know, Australia’s transport system is not that bad. There are plenty of roads, there are plenty of large roads. The issue is how much road space have we got relative to how many cars are trying to get...

TONY JONES

Let’s go back to our questioner. Do you have many other alternatives other than using...?

BILL PARKER

To go and live in Singapore, because we’ve discussed that. That’s how much we love the train system, but that’s as a tourist on a day-to-day basis. We see people commuting quite regularly on the train system.

Dr JAY SONG

I lived in Singapore for five years. I was born in South Korea, lived in the UK. Bob, you talk about the population growth rate in Australia is growing fast compared to other developed countries, but the other developed countries, they have a huge population. So, they don’t have to grow more, but we are a big country. Big, Australia, land-size wise. But population wise, we are quite small. 25 million people only. So we still have room to grow and to have more people who can come here willingly and to contribute to our society.

TONY JONES

Jay, I’m going to go to Tim Flannery there, because I suspect he might disagree with the general position. But what do you think, first of all, Tim, about the whole argument we are hearing that people would be much more likely to accept higher population growth if the infrastructure was there?

TIM FLANNERY

Well, our permission to allow that growth should be conditional upon that infrastructure actually being embarked upon. Why always the other way around? So, you know, there’s no trust in this. So, just to go to that issue of, yes, we’re a big country, and Canada is a big country and Antarctica is a big continent as well, there’s a lot of big places in the world, but the habitability is the thing. And around Australia, if you look at our capital cities, you can see the stress we are already under.

So in Perth and Adelaide, for example, 40% of their water supply already comes from desalinisation, yeah? Melbourne with its huge desal plant has bought itself about a decade of grace, of water security. Beyond that, things are going to get difficult again. We grow enough food to feed about 60 million people, but we export a lot of that, and high-quality food like seafood we import quite a lot. So, it’s a big land, but it is not a very fertile land. And its water resources are limited.

Dr JAY SONG

Of course, yes.

TIM FLANNERY

So we have to look at all of those factors as we grow. And with the impacts of climate change, places like Western Sydney are going to really start feeling the heat, because the heatwaves are getting longer, hotter and more frequent. The infrastructure we are building isn’t fit for purpose for that future. And I think we are going to struggle, I really do.

TONY JONES

Jay, do you accept that Australia may not be in the same category as the big population Asian countries because the climate is different?

Dr JAY SONG

I believe in Australians. Australia is a very innovative country. And Australia is investing a lot of money on R&D and renewable energy and can build better infrastructure, so that it can accommodate more people coming, so there is a great deal of potential and improvement for future generations.

TONY JONES

I’m going to go to our next question, it’s from Ruth Wallace. Once again, it’s about the pressures the infrastructure lack. So, Ruth, go ahead.

HOUSING DENSITY SCHOOLS

RUTH WALLACE

Yes. Like many schools in Sydney, my children’s primary school has grown from 350 children 10 years ago to over 1,000 children this year. The continued approval of high-density housing developments and the desirability of those suburbs in which these are places pressure on local services. Is state government courageous enough to place limits on housing density or make it a priority to fund new schools?

TONY JONES

John Daley, I’ll go to you, because obviously you’ve studied this, the Grattan Institute has looked at this very closely in Melbourne and, actually, around the country.

JOHN DALEY

Well, I hope that what our state governments do is get their act together on schools. Because the evidence is overwhelming – if we want our cities to be affordable and our housing to be affordable, we need more of that medium and high-density development. But the reality is most of the jobs we are creating are towards the centre of our cities and if you’re trying to commute to those jobs from the very far edge of those cities, it’s a very hard thing to do.

And, of course, Australian cities are very sparsely populated by global standards. I mean, obviously relative to old cities like Berlin and Rome. But even if you take a city like Toronto which is substantially larger in terms of population than Sydney and Melbourne, it’s smaller in terms of footprint, essentially because it is built up more. It doesn’t mean it’s got to be 30 storeys as far as the eye can see. It’s worth remembering that Paris is one of the densest cities in the world and most of it is only four storeys. So we can make our cities much denser, but you are absolutely right, we need to build the schools behind them.

TONY JONES

Just put some of the figures around it. From your report, we need 220 new schools in Victoria in the next 10 years. I think it’s 213 in New South Wales, nearly 200 in Queensland.

JOHN DALEY

Yeah, and most of them, towards the middle of our cities, and the middle ring suburbs of our cities, essentially because we are seeing an increase in density, particularly in Sydney, in the middle ring and in Melbourne right in the centre. And I don’t think that people 15 years ago believed that they would be families. Now, things have changed. A lot more families are prepared to live there, and so we need to make sure that politicians get behind that and invest the money in schools.

Why don’t they? Because there is a real pressure to build the new school wherever the people are yelling the loudest. So, certainly Victoria has had a pretty sensible-looking plan for a long time about what the priorities were given the actual population movements, but we often didn’t follow the plan, as the Auditor-General found. And so it’s something where you need discipline, you need to put the money into it and you need to actually stick with the priorities that go with the population rather than wherever there happens to be a local lobby group that’s a bit louder than all the other local lobby groups.

TONY JONES

OK. I’ll go to Bob.

BOB CARR

A bit of honesty on rezoning, on densities, would be much appreciated. A lot of the advocates of Big Australia seem to be concentrated in suburbs that don’t feel any of the pressure the rest of us feel. I’ve made the point – I made it just to be a bit cheeky – about Point Piper. If you went through the streets of Point Piper, every house would tell you – because they’re investors and one famous politician – they would tell you that they believe in a Big Australia. But they’re not getting any of the pleasure of the Big Australia. There’s no high-rise being planned there.

I’ll give you another example of dishonesty. Barry O’Farrell declared, when he was premier of New South Wales, he was a great supporter of a Big Australia, he wanted more ambitious immigration. One of his first planning acts as premier was to cancel plans for high-rise in his electorate along the North Shore rail line in Ku-ring-gai. Now, you can’t have that sort of dishonesty. You have got to say – here is one idea for a population plan for Australia, and that is...

TONY JONES

Which we don’t have, Bob.

BOB CARR

Exactly. Well, here’s one notion that belongs in it, to link increases in immigration to results in rezonings and let the Australian people understand the linkage that exists here. If you are running immigration at the levels we’ve seen, you are going to be living a high-density future. If you want to be honest about that and say, “We will live at Singapore densities or Hong Kong densities,” then you are being far more honest than the people in Canberra who set these immigration levels and have nothing to say about money for infrastructure or the resultant rezonings required.

TONY JONES

Jane wants to get in here.

JANE FITZGERALD

I think, again, to focus on the good news and what’s changed and what’s actually happening in Sydney right now, right now the Greater Sydney Commission, who are a bunch of planning experts, they’re not a bunch of politicians, are sitting down and looking at every part of Sydney and drawing up a plan. They’re drawing up a plan with housing targets that doesn’t include a high-density apartment block for every suburb, but it might include more town houses, more four-storey blocks of apartments in suburbs that I live in, or suburbs that you live in as well.

It will also include, hopefully, better retirement living for our ageing population, so people can age in place within their suburbs and it will also include, no doubt, fabulous, sustainable residential communities on the urban fringe as well.

BOB CARR

What about Point Piper?

TONY JONES

I’m going to pause all of you, because I’m gonna just tell my colleagues we’re gonna jump ahead to question number eight, and that is Jeanette Brokman, because it’s right on topic. Go ahead, Jeanette.

DEVELOPERS VS NIMBYS

JEANETTE BROKMAN

In our brave new world in New South Wales, we are seeing high-rise schools funded by developers and transport systems privatised, while jobs are casualised and suburbs turned into a developers’ paradise. Government slogans tell us “We’re Building Tomorrow’s Sydney” while taxpayer-funded projects go off the rails and the equity divide ever increases. With communities that fight back branded NIMBYs and government employees prevented from speaking out, what can we do to stop this Gordon Gekko type of world?

TONY JONES

John Daley, I’ll start with you. Are we living in a Gordon Gekko type of world?

JOHN DALEY

Well, that depends how we manage it. And I think one of the issues is if you want your children to be able to afford to buy housing, you will need to build more housing. It is pretty simple. And so it is all very well to say, well, I agree that there should be more building, but just not in my suburb, in the suburb next door, and then my children can live in the suburb next door, then we wind up in a world that is not far from where we have been for much of the period between about 2007 and 2013 in which population growth got well ahead of building growth.

Now, that said, there are plenty of things that we can have a look at, so for example, a lot of the time at the moment we rezone land, we change the rules so that you can build a lot more on it and we, essentially, just give that away. And whoever happens to own it at the time gets a huge windfall, and some very elegant work has been done in Queensland that shows that very disproportionately it’s property developers who own land at the time it gets rezoned which might just be coincidence, but I’m guessing not! The ACT has actually solved this. What the ACT does is that it has a whole series of rules that says every time the land gets rezoned, we know that creates a big uplift in value and essentially we take a lot of that back in tax. And that is something we need to look a lot more at. When we are going to rezone places to accommodate this growth, we say that’s not just a free kick for whoever happens to own it, that is something that we effectively take some of the value back so that it’s not just a game for Gordon Gekkos to get rich, not by actually building houses, but by holding land in the right places at the time it gets rezoned.

TONY JONES

John, let’s pick up on another point in the question, then I’ll come to Tim. You are the one, essentially, telling governments that people should not be able to say, “Not in my backyard.” You are warning about the Nimbyism. Our questioner, who’s got her hand up. Go ahead.

JEANETTE BROKMAN

I guess I just wanted to respond to John. I live in a suburb that has its fair share of heavy lifting and what’s happened is that incomes have declined because properties are very tiny now and they are very high vertical villages and incomes have declined, yet the land values have soared, because of the high densification. As a consequence, the suburb has become more expensive and has priced out the market and so I guess that was my question was – it is becoming a kind of Gordon Gekko type of world, with those that have and those that don’t have.

TONY JONES

OK. John, should people be fighting harder to say, “No, I don’t want that in my backyard?”

JOHN DALEY

Look, I hope not. I think you’re right, land values have probably gone up, but the cost of an individual dwelling is probably much lower than it would be otherwise. Now, I also agree, if your suburb is the only one that is seeing all of this development happening and Point Piper, or wherever, is not, then obviously that’s unfair. And we did...

TONY JONES

Why? Because, like, 50 people could live in Malcolm Turnbull’s house?

JOHN DALEY

Well, it’s also... If you certainly look at what’s been happening in Melbourne where we could actually get the data on this, what’s been happening is that the suburbs with the highest incomes have by and large been the ones that have been most successful at preventing development and slowing it down.

BOB CARR

Exactly.

JOHN DALEY

They are also the ones where, according to the Reserve Bank, the premiums are highest for the right to develop. Now, that’s a problem. And in a world in which politicians, at least in some states, have essentially said – “You can do it in the suburbs where the people vote for the other side, but you can’t do it in the suburbs that vote for my side of politics” – that’s a problem.

TONY JONES

OK, I’m going to come to the Property Council in a moment, but Tim wants to get in.

TIM FLANNERY

Yeah, look, Jeanette, that vision you just outlined of Australia is what I feel too. And it really worries me. And I just feel that our... We have left it to the experts, we have left it to politicians and we have ended up with a mess. And it’s...I have got enormous faith in the common sense of just average Australians. And I can’t think of a better way of dealing with this than to put the power back into the hands of well-informed average Australians, through something like a jury system. You know, 200 of us chosen at random and given access to all the facts and asked to make a decision and given a time to do it and paid to do it would come up with a decision that would be representative, I believe, of what Australians want.

TONY JONES

How would the Property Council deal with the jury deciding where the developments go?

(LAUGHTER)

JANE FITZGERALD

Look, I think that it would be better than local politicians campaigning on the basis that they’re going to stop growth in a suburb, when they actually aren’t well placed to do that, or shouldn’t do that to house our kids. We know in Sydney from the Reserve Bank last week released a report that said zoning restrictions in Sydney are adding $489,000 to the price of a home. That’s extraordinary. If we don’t try to do density well, if we don’t try to do density better, and we don’t look at each suburb, with its existing built form in place, I’m not suggesting there should be apartment blocks in every suburb in Sydney. What I’m saying is that every suburb in Sydney, every community in Sydney, if you want your kids to be able to live within 100km of where you live, it needs to be part of a conversation about how we do density well. And that’s what’s missing. That requires some serious political leadership. Otherwise, you’re paying $490,000 extra for the price of a home. The Reserve Bank data, not the Property Council.

TONY JONES

OK. I just want to hear from Jay on this. You have lived in Singapore, you know the situation in very high-density cities with high populations. Do they just give up on the idea of having leafy suburbs and backyards and all of those sort of things, and is life any better or worse as a result?

Dr JAY SONG

Well, before I moved to Singapore, I thought Singapore was just all grey high-rise buildings. But actually, they planned it very well. So patches of green areas, so there is a great mixture of, you know, high-rise buildings. But Singapore has a policy, you know, to give the public housing to their citizens so most of the Singaporean citizens own their house. Public housing also have a quota for a certain number of Chinese citizens and the Malay and Indian so that they can have racial harmony in one apartment block. Singapore is a high-density, you know, it’s a city state. But I don’t think Sydney or Melbourne is going to be like Singapore or Hong Kong. I think we are more likely to be New York, London...

TONY JONES

So how many people in Singapore?

Dr JAY SONG

Five million.

TONY JONES

OK, Sydney is going to have eight million, Melbourne is going to have more than eight million...

Dr JAY SONG

Yeah, London has eight.

TONY JONES

Are you sure we won’t look like those cities?

Dr JAY SONG

This is why we are having this conversation today, isn’t it?

JOHN DALEY

And bear in mind, Tony, I don’t know precisely what it is, but I would guess that Sydney and Melbourne have something like 20 times the footprint of Singapore.

BOB CARR

Exactly.

JOHN DALEY

You do not need to make Melbourne and Sydney look like Singapore or Hong Kong in order to double their population. Nothing like it.

TONY JONES

OK, nonetheless, a good deal of frustration out there. Let’s got to Jed Smith. Jed?

RENTS AND WORKING PEOPLE

JED SMITH

Yeah, I was raised by a single mother in inner city Sydney. She is in her 50s now, and those people are doing it pretty tough, she’s barely hanging on by a thread to the rental market. My question is, who or what decides how much we should pay for the privilege of having a roof over our heads? Who or what decided that the working-class in this country should have to work six days a week and commute between two to five hours a day for 40 years, just so they can afford a home? Who decided that we should get little more than an hour a night, and one full day a week to spend with our loved ones doing the things that bring us joy and happiness?

TONY JONES

Bob Carr. I mean, did you hear this kind of...?

(APPLAUSE)

TONY JONES

It’s a sense you get, and you hear it in the audience, that life has changed underneath us while we weren’t watching.

BOB CARR

Yeah, and to a large extent, it’s determined by raw market forces that we’ve opted to allow to determine the way we live, by the laws of supply and demand. And if we say, if we say there are going to be 100,000 extra residents in a Sydney, in a Melbourne each and every year, we will have an effect on how we live. We can’t alter that. On journey times and on wages, on wages. We haven’t discussed, one of the impacts of high immigration, and that is downward pressure on wages. We had the Reserve Bank tell us that wages are too low. There is not enough growth in wages. And the reason is, the reason is, we’ve got extraordinarily high immigration as part of our economic system. The upward pressure on housing prices, that has had a huge impact on how Australians live now.

TONY JONES

Bob, I’ve got a few heads shaking over this side. I’m going to hear from...

BOB CARR

I’m sure you have!

TONY JONES

I’m going to hear from Jay and then go to John. So are migrants bringing down wages?

Dr JAY SONG

You keep going on about migration, and finger-pointing migration as an issue. The issue is the infrastructure. You have to keep up...

BOB CARR

Not with wages. That’s got nothing to do with infrastructure. We are talking about wages. We are talking about downward pressure on wages.

Dr JAY SONG

Migrants create jobs, Bob. They pay tax, they also create jobs...

BOB CARR

That is not the issue. That’s not the issue.

Dr JAY SONG

What’s the issue, then?

TONY JONES

Hang on, Bob. Hang on, Bob. I’ll come back to you. But we’re going to hear from Jay.

Dr JAY SONG

The issue is not about immigration. I mean, they come in, most of them, 60% of them, as I said, at the beginning of my conversation, are skilled migrants. And they are regularly, the occupation list is regularly updated by the Department of Industry and together with the Department of... used to be Immigration and Border Protection, now it’s the Home Office, so they are doing a good job to keep checking the Australian businesses who need skills shortages in certain industries. We still need those skilled migrants who can contribute to our society.

BOB CARR

Jay, with respect, not according to the latest...

TONY JONES

Hang on, Bob. Hang on, Bob, please. I said I’d go to John. I want to hear from him.

JOHN DALEY

So, Bob, there is lots of OECD research. This is something that people have looked at a lot. And the consensus of that essentially seems to be that immigrants by and large do not push down wages. And particularly not when, as Australia has, those migrants are skewed young and skilled. In fact, in that world, they probably, if anything, push average wages up a little bit. That is what the evidence says, both in the OECD, and the Productivity Commission has come to more or less the same conclusion. Now, that said, you are absolutely right that migrants do, all other things being equal, increase house prices, but that depends on, what do you do about construction? So, Sydney, this year, is going to deliver in the order of about 35,000 extra dwellings, that, I think, is the highest on record. It needs to be, because population growth is almost the highest, is the highest on record in Sydney. But at that level, we would essentially be building enough housing given the increase in population. The catch is we didn’t do that for the last ten years. We ran migration at this level, we did not see substantial increase in housing, largely because the planning system locked it up, and that’s why we saw house prices go through the roof.

TONY JONES

OK, Bob, a quick response, ‘cause I’ve got to go to another question.

BOB CARR

A very quick response is about the failure of our Skilled Migration Program. The most recent study that I read by Bob Birrell, shows that you could abolish it tomorrow without any employers seeing the difference. We are importing professionals, we are importing professionals who are unemployed. Now, we’ve got to reassess the notion we hold that the Skilled Migration Program as we make it work is delivering relief from skill shortages.

TONY JONES

Jane wants to respond to that, a quick response. And then I’ll move on.

JANE FITZGERALD

I actually want to come back to Jed’s question. Because I think it’s a really valid one in terms of how we make our lives, as a whole, work better. And part of the answer, a big part of the answer, Jed, is that we have to do the planning that’s currently going on now. But then we have to actually implement it so that you can have a job that is near where you live so you are not commuting for two hours and not getting time to spend with your mum or your kids, or whatever it might be. We need to do that, we need to make sure they are real jobs, we need to make sure that the transport between those two locations is good, but we also need to make sure that you’ve got a park that you can go and kick a footy around.

TONY JONES

And we probably need to make sure that houses don’t cost a million dollars.

JANE FITZGERALD

Absolutely. And I completely agree with John’s point. His report made it incredibly eloquently last week, as did the RBA report, that if we don’t fix the planning system, and, sure, we delivered a record number of houses last year and we need to deliver 725,000 more by 2036. We’re going to have to do it better for decades.

TONY JONES

OK. We’ve got some people with some slightly different ideas on how you can fix this. One is Bob Beckett. Go ahead, Bob.

REGIONAL SOLUTION/HIGH SPEED RAIL

BOB BECKETT

So far we have talked a lot about solutions that are Sydney-centric. So they involve increasing density in infrastructure within Sydney and the current vision is one of three cities between the current CBD, Parramatta and around Western Sydney airport. My question is, is it not also time to seriously consider improving high-speed transportation with nearby regional centres, such as Newcastle, Gosford and Wollongong, to put them within a realistic commutable distance and relieve some of the pressure from Sydney itself?

(APPLAUSE)

TONY JONES

Bob... John, I beg your pardon. John Daley, it seems we are talking about infrastructure, and this is one of the big ones, we’ve got these huge mega-cities coming, but why not just expand the populations in regional centres and create proper transport connections between them?

JOHN DALEY

Well, it depends what we think we are doing. If what we think we’re doing is creating a whole bunch of extra jobs in regional centres, then I think we’re going to be disappointed. We have 117 years of official policy to do that, and so far, 117 years of failure. So I’d be surprised if this time is different. If we think we’re doing it because we are essentially making Newcastle and Wollongong, to some extent, dormitory towns for Sydney, well, that’s doable. But you’ve got to ask, well, why would I bother doing that rather than just making sure that the rail link works from the edge of Sydney, which is by definition, closer than either Newcastle or Wollongong? And better still, why wouldn’t I increase the density in the middle rings of Sydney, where, inherently, I’m only about half an hour’s commuting distance from the centre of Sydney using existing transport networks?

TONY JONES

Why not...? John, why not do both things? And then you’ve got the opportunity to develop regional Australia whilst simultaneously developing the inner rings or the middle rings, as you call them.

JOHN DALEY

You might well do both but I think what you’ll find is that commuting all the way to Sydney from Newcastle and from Wollongong is actually a lot harder than it sounds. I have staff members who commute from Castlemaine which is, you know, it’s about an hour’s commute, it’s probably a bit similar, and they’ve rapidly got to the point, after a year and a half, of saying, you know, “John, I never get home before dark, it’s just too hard.”

TONY JONES

They don’t do it by high-speed rail, which was the question. So, Tim.

TIM FLANNERY

Whether you do it by high-speed rail or by some other means, high-speed rail just pushes it out further, I think. And what John’s saying is absolutely right. You look at towns like Ballarat and some of the areas around Melbourne, where they’re sort of dormitory suburbs, it’s actually had a big effect on the town and life in those towns. You know, I think we’ve got so many infrastructure problems at the moment that are crying out to be fixed. Let’s start with the stuff we really need to do now, to serve the populations that are already really struggling, rather than looking at these sort of projects.

TONY JONES

I’m going to move on quickly to another question from Rachel Chiu. Rachel is in the middle there. Go ahead, Rachel. Thank you very much.

REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT - MIGRATION

RACHEL CHIU

So, my question is do you think it’s viable to develop Australia’s regional centre as a way of alleviating the pressure on our major cities? And if so, would it create...if we create industry by directing migration or refugee settlements to these regional centres?

TONY JONES

I’ll start with Jay. What do you think? We talked about high-speed rail – you can come in on that as well – because, obviously, there’s huge infrastructure in high-speed rail in China, in Japan and many other Asian countries. But also, that’s a question really saying, should we send migrants to regional centres? Should we make it compulsory?

Dr JAY SONG

Sure. Our government has tried already to settle those 150 Karen refugees from Myanmar to settle in Victoria, regional Victoria, called Nhill, and that was very successful. They did it with the local community, who had a plan, who can hire those newly arriving refugees to give them job and give them livelihood and it worked very well.

And there is a study by Regional Australia Institute that migrants stay in those regional states and regional areas and it works for them...also for the community, the local community, to grow. So, yeah, I mean, growing in not just the big cities, but spreading out and giving more job and housing opportunities for those incoming migrants, or the temporary migrants, to move to...relocate to those regional cities, that would be a great solution.

TONY JONES

Bob, I’ll bring you in here – decentralisation was one of the big plans of the Whitlam government back in the early ‘70s. It just never happened, did it?

BOB CARR

It’s part of Australia’s DNA. We love the idea. But America is the continent where that can happen. Inland cities based on strong river systems, rivers flowing down the Rocky Mountains. We haven’t got that. Two problems...

TONY JONES

We don’t have the Rocky Mountains. Plenty of rivers.

BOB CARR

Two problems... Well, every river on the Australian continent would fit in the Mississippi and the Mississippi wouldn’t notice it. There are geographic limits about Australia and two really do undermine the happy faith we, as Australians, have sometimes invested in decentralisation.

One is water. Don’t forget, in the last drought, that you had inland cities running out of water. It was particularly acute in Goulburn and Canberra, for example. And that is really a restraint on how you could build population in those centres. And, second, decentralisation only works where you have some terrific value-adding industry. An efficient abattoir, for example, or a mine, like the Cadia gold and copper mine in Orange.

TONY JONES

Or the Federal Government, like in Canberra, where there’s no high-speed rail.

BOB CARR

Exactly. Beautiful example. And by the way, talking so fondly as we are of Canberra, Canberra, the city, where immigration targets are set for all of Australia, the targets that Sydney and Melbourne have got to cope with, Canberra has the lowest population densities of any capital city in Australia.

TONY JONES

OK, Bob, you mentioned America and we have a question picking up on this idea of smaller cities from Jennifer Crawford.

SMALL CITIES

JENNIFER CRAWFORD

Why don’t we do small cities in Australia? Outside the capital cities and their associated conurbations, the largest inland city in New South Wales is Albury-Wodonga, with a population of just under 90,000. Next is Coffs Harbour with 69,000 and Wagga with 56,000. If you look around the world, there are many famous small cities. York in the UK has 200,000, Bristol in the UK has 428,000, Lyon in France is 480,000, Portland in the USA is 640,000 and even Seattle in the USA is only 700,000 people. How much more pleasant would life be in small Australian cities of between 250,000 to 500,000 people? As an architect, I’m really excited by the idea. Why can’t we seem to do it?

(APPLAUSE)

TONY JONES

Jane, why can’t we do it? Bob said we don’t have the big rivers, but what do you think?

JANE FITZGERALD

I think that when we’re talking about planning cities of tomorrow, smart cities of the future, there are some things that we know that work, and I was just thinking about Newcastle and Wollongong. And one of the things that both of those cities have are world-class universities, which are very much an attracter for innovation, for students, and that is why Newcastle and Wollongong are actually on a really good growth trajectory at the moment, that I think what you need to be able to do, apart from getting the transport links right, is you need to have that attracter, as Bob mentioned.

But also a part of it is about branding and about selling yourself to the world. And I know that we’ve got members in Newcastle and Wollongong who are working through that process with the universities in those towns.

TONY JONES

I’d just like to quickly go back to our questioner, who has her hand up. Jennifer, go ahead.

JENNIFER CRAWFORD

Well, Bathurst has Charles Sturt University and there’s also the University of England in Armidale. My aunty lived in Armidale. It’s quite a pleasant town and not as hot as other towns in western New South Wales. So, I’m kind of wondering why can’t we, as you suggest, piggyback off those university towns and make them grow to a size that can sustain theatre, good coffee, yoga classes, and all the stuff that us Inner-West hipsters want to move to?

TONY JONES

Actually, I’ll go to Tim there. Could we do that in Australia? Could we have lots of smaller cities that still had reasonable populations and be good places to live?

TIM FLANNERY