The Transition Towns Movement; its huge significance and a friendly criticism

Source of illustration

The only way the global sustainability and justice predicament can be solved is via something like the inspiring Transition Towns movement. However thought needs to be given to a number of themes or it might fail to achieve significant goals.

The Transition Towns movement began only about 2005 and is growing rapidly. It emerged in the UK mainly in response to the realisation that the coming of “peak oil” is likely to leave towns in a desperate situation, and therefore that it is very important that they strive to develop local economic self sufficiency.

What many within the movement probably don’t know is that for decades some of us in the “deep green” camp have been arguing that the key element in a sustainable and just world has to be small, highly self sufficient, localised economies under local cooperative control. (See my Abandon Affluence, published in1985, and The Conserver Society, 1995.)

It is therefore immensely encouraging to find that this kind of initiative is not only underway but booming. I have not the slightest hesitation in saying that if this planet makes it through the next 50 years to sustainable and just ways it will be via some kind of Transition Towns process. However I also want to argue that if the movement is to have this outcome there are some very important issues it must think carefully about or it could actually come to little or nothing of any social significance. I want to suggest l below that there is a need for a much more focused and detailed action strategy, giving clearer guidance to newcomers, and following a much more radical vision than seems to be informing the movement at present.

My comments won’t make much sense unless I first make clear the perspective on the global situation my comments derive from. Most people would reject this view as being too extreme.

Where we are, and the way out.

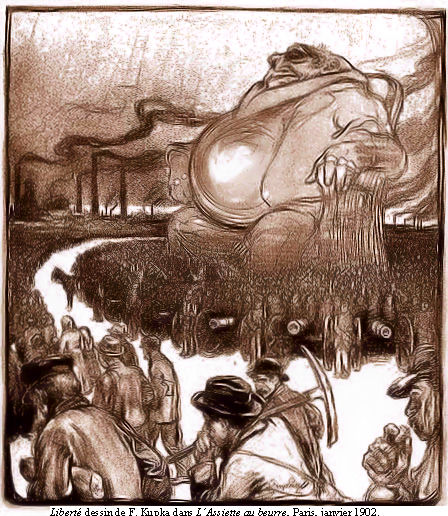

The many alarming global problems now crowding in and threatening to destroy us are so big and serious that they cannot be solved within or by consumer-capitalist society. The way of life we have in rich countries is grossly unsustainable and unjust. There is no possibility of the “living standards” of all people on earth ever rising to rich world per capita levels of consumption of energy, minerals, timber, water, food, phosphorous etc. These rates of consumption are generating the numerous alarming global problems now threatening our survival. Yet most people have no idea of the magnitude of the overshoot, of how far we are beyond a sustainable levels of resource use and environmental impact. ln addition our way of life would not be possible if rich countries were not taking far more than their fair share of world resources, via an extremely unjust global economy, and thereby condemning most of the world’s people to deprivation.

Given this analysis of out situation, there must be transition to a very different kind of society, one not based on globalisation, market forces, the profit motive, centralisation, representative democracy, or competitive, individualistic acquisitiveness. Above all it must be a zero-growth economy, and most difficult of all, it cannot be an affluent society.

However almost everyone in the mainstream, from politicians, economists and bureaucrats down to ordinary people, totally fails to recognise any of this and proceeds on the comforting delusion that with more effort and technical advance we can solve problems like greenhouse without jeopardising our high “living standards” or the market economy or the obsession with growth. Our fundamental problem therefore is one of ideology or consciousness. Most people in this society are a very long way from having the understandings and values required for transition. Most seem not to know or care that they live as well as they do because the global economy is extremely unjust, or that affluence and growth are incompatible with ecological survival. Changing that consciousness is the key to transition.

I have appendixed some of the support for this perspective on out global situation. A more detailed account can be found at http://ssis.arts.unsw.edu.au/tsw/

Given the above view of our situation, we must work for transition to a very different kind of society. I refer to it as The Simpler Way. Its core principles must be

- Far simpler material living standards

- High levels of self-sufficiency at household, national and especially neighbourhood and town levels, with relatively little travel, transport or trade. There must be mostly small, local economies in which most of the things we need are produced by local labour from local resources.

- Basically cooperative and participatory local systems,

- A quite different economic system, one not driven by market forces and profit, and in which there is far less work, production, and consumption, and a large cashless sector, including many free goods from local commons. There must be no economic growth at all. There must be mostly small local economies, under our control via participatory systems.

- Most problematic, a radically different culture, in which competitive and acquisitive individualism is replaced by frugal, self-sufficient collectivism.

Some of the elements within The Simpler Way are, -- mostly small and highly self-sufficient local economies with many little firms, ponds, animals, farms, forests throughout settlements – participatory democracy via town assemblies – neighbourhood workshops – many roads dug up – “edible landscapes” providing free fruit and nuts – being able to get to decentralised workplaces by bicycle or on foot voluntary community working bees – committees - many productive commons in the town (fruit, timber, bamboo, herbs…) – having to work for money only one or two days a week – no unemployment – living with many artists and crafts people – strong community --small communities making many of the important development and administration decisions.

Simple traditional alternative technologies will be quite sufficient for many purposes, especially for producing houses, furniture, food and pottery. Much production will take place via hobbies and crafts, small farms and family enterprises. However modern/high technologies and mass production can be used extensively where appropriate, including IT. The Simpler Way will free many more resources for purposes like medical research than are devoted to these at present, because most of the present vast quantity of unnecessary production will be phased out.

There could still be many small private firms, and market forces could have a role, but the economy must be under firm social control, via local participatory processes. Thus local town meetings would make the important economic decisions in terms of what’s best for the town and its people and environment. Rational assessments of basic necessities would be the main determinants of economic activity. We would not allow market forces to bankrupt any firm or dump anyone into unemployment. We would make sure everyone had a livelihood. The town would have to work out how to adjust its economy in the best interests of all.

Thus only an Anarchist form of government could work. Only if all participate in making the decisions and implementing them without authoritarian institutions will people enthusiastically contribute to effective town functioning. (There would still be some functions for state and national governments.)

Because we will be highly dependent on our local ecosystems and on our social cohesion, e.g., for most water and food, and for effective committees and working bees, all will have a strong incentive to focus on what is best for the town, rather than on what is best for themselves as competing individuals. Cooperation and conscientiousness will therefore tend to be automatically rewarded, whereas in consumer society competitive individualism is required and rewarded.

What we will be doing is building a new economy, Economy B, under the old one. Economy B will give us the power to produce the basic goods and services we need not just to survive as the old economy increasingly fails to provide, but to give all a high quality of life. The old economy could collapse and we would still be able to provide for ourselves.

Advocates of the Simpler Way believe that its many benefits and sources of satisfaction would provide a much higher quality of life than most people experience in consumer society.

It must be emphasised that The Simpler Way is not optional. If our global situation is as has been argued then a sustainable and just society in the coming era of scarcity has to be some kind of Simpler Way.

The Transition.

In my view the contradiction between consumer-capitalist society and The Simpler Way is so enormous that we are unlikely to make it. Nevertheless it is clear what we must try to do. Following are a few of the key points to consider in the discussion of transition strategy.

There is not much to be gained by trying to fight against the present system directly. Not only is it far too powerful and the dissenting forces far too weak, there isn’t time to beat it in head-on conflict. More importantly, even if we could for instance take state power, either by violent revolution or green parliamentary action, it would not be of any value to us whatsoever. State power cannot build self sufficient, self-governing local economies full of conscientious, responsible, creative, happy citizens. If the old industrial centralised system was still a viable model for a post-revolutionary society then maybe coups and revolutions and rule from the top might be relevant – but that model is irrelevant now.

Transition must therefore be a grass roots process whereby people slowly develop the consciousness, the skills, the local systems and infrastructures that will enable ordinary people to come together to run their own local communities. Much diminished state governments could have a valuable although secondary role, but we will have to do most of the thinking, work and learning ourselves in the towns and suburbs where we live. This is a basically Anarchist vision, and given the need for localism, frugality, participation, cooperation etc. set by the coming era of intense scarcity, we will have no choice about this.

The good society can and must be, as the Anarchists say, “prefigured”. We can begin now building aspects of it here within the failing old system, and indeed there is no other way to get from where we are to the kinds of settlements and systems we must have eventually.

There is no chance of significant change while the supermarket shelves remain well-stocked. Almost everyone will stolidly plod on purchasing, watching sport and playing electronic games until scarcity hits with a jolt. However, as the old systems run into more serious problems, people will come across to join us, realising that we are enjoying the benefits of the new ways. When oil starts to get seriously scarce people will see that they must either take up our examples or starve.

This revolution could therefore be smooth and non-violent. If we are lucky the old system will more or less just die away as people “ignore it to death”. The super-rich will resist desperately but without oil and confronted by millions of scattered people in their towns and suburbs doing their own thing they will have little capacity to stop us.

It is therefore of the utmost importance that we get the alternative examples up and running. Nothing will be more persuasive than pockets here and there where The Simpler Way can be seen as being lived and enjoyed within mainstream towns and suburbs.

Until around 2000 the basic pioneering work had been done by the Global Eco-village Movement. It’s possibly thousands of small communities have shown that a better way is possible. However the world’s soon-to-be 9 billion people cannot all form Eco-villages on green field sites. What they can do, however is transform the settlements they are living in into Eco-villages. And this is what the Transition Towns movement is in principle about.

The Transition Towns Movement.

The Transition Towns movement has emerged very rapidly and is spreading around the world. Towns in the UK have led the way, the best known being Totness. Although Rob Hopkins and his colleagues seems rightly to receive most of the credit for getting the movement going, its rapid spread testifies to a strong general grass roots readiness to take up the idea. There are now towns in several other countries joining the movement, including Australia and New Zealand. The website is inspiring, linking to many towns and projects, reflecting energy and enthusiasm. A handbook and other documents have been published.

The key concept referred to is building town “resilience” in the face of the coming peak oil crisis. The kinds of activities being taken up include, “re-skilling” whereby courses are run on things like bread baking, the planting of commons, e.g., nut trees on public land, local food production and marketing, especially community supported agriculture, and the encouragement of volunteering. These are not new ideas of course, but it is important that they are being linked together in whole town strategies for resilience. Notable is the fact that these initiatives have not come from states, governments or official bodies, but from ordinary people.

Concerns.

Despite my enthusiasm, I have serious concerns about the movement and I want to suggest some issues that require careful thought. If we do not get them right the movement could very easily end up making no significant contribution to solving the global problem.

Goals? Only building havens?

First there is the danger that it will only be a Not-In-My-Backyard phenomenon, that it will be about towns trying to insulate themselves from the coming time of scarcities and troubles. This is a quite different goal to working to replace consumer-capitalist society. It is not much good if your town bakes its own bread or even generates much of its own electricity, while it goes on importing hardware and appliances produced in China and taking holidays abroad. It will still indirectly be using considerable amounts of coal and oil in the goods it imports. The wider national society on which it depends for law, postal services, security etc. cannot continue as it is unless it maintains the Third World empire from which it draws so much wealth. Unless we eventually change all that then our Transition Towns will remain part of consumer-capitalist society, and will go down when it goes down.

In other words, given the view of the global situation sketched above the top concern must be to work to make sure the movement is explicitly, consciously and primarily about nothing less than contributing to global transition away from consumer-capitalist society. That kind of society is the cause of our problems, it is leading us to catastrophe, it is not possible for all, it is only possible for us because the Third World is plundered, and it destroys the environment. It condemns billions to dreadful conditions. Our top priority must be to replace it, as distinct from making our town “resilient” in the face of the trouble it is causing. This vision is not evident in the Transition Towns movement literature or in its web sites. If it was the movement would probably be much less popular.

Does this mean I should accept that I want to see a quite different movement, one that is for quite different goals, and therefore I should back off and not lecture the existing movement that its goals are mistaken, and go form my own? Perhaps this is so, but my hope obviously is that the existing movement will be willing to endorse goals that are wider and more critical/radical than they are at present. If it doesn’t then I don’t think it will make much difference to the fate of the planet. I have thought in terms of a Simpler Way Transition Strategy whereby we try to work within Transition Towns initiatives to get the broader vision and goals accepted. The practical involvement in building town self-sufficiency is the best means for doing that.

What are the sub-goals? The lack of guidance.

The website, the handbook and especially the 12 Steps document are valuable, but they are predominantly about procedure and it is remarkably difficult to find clear guidance as to what the sub-goals of the movement are, the actual structures and systems and projects that we should be trying to undertake if our town is to achieve transition or resilience. What we desperately need to know is what things should we start trying to set up, what should we avoid, what should come first. Especially important is that we need to be able to see

The advice and suggestions you do find in the literature are almost entirely about how to establish the movement (e.g., “Awareness raising”, “Form subgroups”, “Build a bridge to local government”), as distinct from how to establish things that will actually, obviously make the town more resilient. There is some reference to possibilities, such as set up community supported agriculture schemes, but we are told little more than that we should establish committees to look into what might be done in areas such as energy, food, education and health.

The authors of these documents seem to be anxious to avoid prescription and dogma, and it is likely that no one can give certain guidance at this early stage, but that does not mean that advice regarding probably valuable projects should not be offered. The lack is most evident in The Kinsale Energy Descent Plan, which does little more than repeat the process ideas in the 12 steps documents and contains virtually no information or projects to do with energy technology or strategies. It lists some possibilities, such as exploring insulation and the possibility of local energy generation, and reducing the need for transport, but again there is no advice as to what precisely can or might be set up. We need more than this; we need to know l how and why a particular project will make the town more resilient, and we need to know what projects we should start with, what the difficulties and costs might be, etc. Just being told “Create an energy descent plan” (Step 12) doesn’t help much when what we need to know how might we do that.

I suggest some possible concrete projects below, drawn from my tentative thoughts on The Simpler Way Transition Strategy. We might eventually realise this is not a good approach, but they indicate the kind or guidance people coming to the movement must be given. Otherwise we run the risk of people not having much idea what to set up, and rushing into exciting activities that are a waste of time, or becoming disenchanted with the failure to make much difference to the town’s situation.

What should be the top goal? Build a new economy, and run it!

I want to argue that the focal concern of the movement should not be energy and its coming scarcity. Yes all that sets the scene and the imperative, but the solution is not primarily to do with energy. It is to do with developing town economic self-sufficiency. The supreme need is for us to build a radically new economy within our town, and then for us to run it to meet our needs.

It is not oil that sets your greatest insecurity; it is the global economy. lt doesn’t need your town. It will relocate your jobs where profits are greatest. It can flip into recession overnight and dump you and billions of others into unemployment and poverty. It will only deliver to you whatever benefits trickle down from the ventures which maximise corporate profits. It loots the Third World to stock your supermarket shelves. It has condemned much of your town to idleness, in the form of unemployment and wasted time and resources that could be being devoted to meeting urgent needs there. ln the coming time of scarcity it will not look after you. You will only escape that fate if you build a radically new economy in your region, and run it to provide for the people who live there.

All this flatly contradicts the conventional economy. We have to build a local economy, not a national or globalised economy, an economy designed to meet needs not to maximise profits, an economy under participatory social control and not driven by corporate profit, and one guided by rational planning as distinct from leaving everything to the market. This is the antithesis of capitalism, markets, profit motivation and corporate control. Nothing could be more revolutionary. If we don’t plunge into building such an economy we will probably not survive in the coming age of scarcity. The Transition Towns movement will come to nothing of great significance if it does not set itself to build such economies. Either your town will get control of its own affairs and organise local productive capacity to provide for you, or it will remain within and dependent on the mainstream economy, and be dumped.

In other words, the goal here is to build Economy B, a new local economy enabling the people who live in the town to guarantee the provision of basic necessities by applying their labour, land and skills to local resources…all under our control. The old economy A can then drop /dead and we will still be able to provide for ourselves. This kind of vision and goal is not evident in the TT literature and reports I have read. There is no concept of a Community Development Cooperative setting out to eventually run the town economy for the benefit of the people via participatory means. The movement at present implicitly accepts the normal consumer-capitalist economy and merely seeks to become more resilient within it.

The need for coordination, priorities and planning – by a Community Development Co-op

If we focus on the goal of local economic developed run by us to meet our needs we realise we must somehow set up mechanisms which enable us to work out and operate a plan. It will not be ideal if we proclaim the importance of town self-sufficiency and then all run off as individuals to set up a bakery here and a garden there. It is important that there be continual discussion about what the town needs to set up to achieve its goals, what should be done first, what is feasible, how we might proceed to get the first and the main things done, what are the most important ventures to set up? Of course individual initiatives are to be encouraged but much more important are likely to be bigger projects requiring whole-town effort.

This means that from the early stages we should set up some kind of Community Development Cooperative, a process whereby we can come together often to discuss and think about the town plan and our progress, towards having a coordinated and unified approach that will then help us decide on sub-goals and priorities, and especially on the purposes to which the early working bees will be put. Obviously this would not need to be elaborate or prescriptive and would not mean people would be discouraged from pursuing ventures other than those endorsed by the CDC.

My impression from the Transition Town literature is that this is something that needs urgent attention. Often it seems that inspired and energetic people are doing good things, but as independent “entrepreneurs” and according to their individual interests and skills. There will always be plenty of scope for this and every reason to encourage it, but the most important projects will be collective, public works which provide crucial services for the town. For instance the building of community gardens, sheds, premises for little firms, orchards, ponds, woodlots and the commons from which free food will come are whole-town projects that will be carried out by voluntary committees and working bees. Before these projects could sensibly begin we would need to have thought out at least an indicative plan which included priority, logistical, geographical, feasibility, research, resource etc. considerations.

What should the CDC actually do?

Following is an indication of the kind of projects that I think of as making up The Simpler Way Transition Strategy. These are the kinds of actual projects I had hoped to find in the TTR literature (and some are there).

• Identify the unmet needs of the town, and the unused productive capacities of the town, and bring them together. Set up the many simple cooperatives enabling all the unemployed, homeless, bored, retired, etc. people to get into the community gardens etc. that would enable them to start producing many of the basic things they need. Can we set up co-ops to run a bakery, bike repair shop, home help service, insulating operation, clothes making and repairing operation.... Especially important are the cooperatives to organise leisure resources, the concerts, picnics, dances, festivals? Can we organise a market day?

One of the worst contradictions in the present economy is that it dumps many people into unemployment, boredom, homelessness, "retirement", mental illness and depression – and in the US, watching 4+ hours of TV every day. These are huge productive capacities left idle land wasted. The CDC can pounce on these resources and harness them and enable dumped people to start producing to meet some of their on needs, thereby moving towards the elimination of employment. To do this is to have begun to set up Economy B. We simply record contributions and these entitle people to proportionate shares of the output. (This is to have initiated our own new currency; see below.)

This mechanism puts us in a position to eventually get rid of unemployment – to make sure all who want work and "incomes" and livelihoods can have them. It is absurd and annoying that governments, (and the people in your neighbourhood) tolerate people suffering depression and boredom when we could so easily set up the cooperatives that would enable them to produce things they need and enjoy purpose and solidarity. (Of course any move to do this would be rejected as “socialism”, which we all know does not work.)

• Help existing small firms to move to activities the town needs, setting up little firms and farms and markets. Establish a town bank to finance these ventures. Making sure no one goes bankrupt and no one is left without a livelihood.

• Organise Business Incubators; the voluntary panels of experts and advisers on gardening, small business, arts etc., so that we can get new ventures up and running well.

• Organise the working bees to plant and maintain the community orchards and other commons, build the premises for the bee keeper...and organise the committees to run the concerts and look after old people...

• Research what the town is importing, and the scope for local firms or new co-ops to start substituting local products.

• Decide what things will emphatically not be left for market forces to determine – such as unemployment, what firms we will have, whether fast food outlets will be patronised if they set up. We will not let market forces deprive anyone of a livelihood; if we have too many bakeries we will work out how to redirect one of them. The town gets together to decide what it needs, and to establish these things regardless of what market forces and the profit motive would have done.

• Stress the importance of reducing consumption, living more simply, making, growing, rep-airing, old things… The less we consume in the town the less we must produce or import. Remember, the world can't consume at anything like the rate rich countries average. As well as explaining the importance of reducing consumption the CDC must stress alternative satisfactions and develop these (e.g., the concerts, festivals, crafts…) It can also develop recipes for cheap but nutritious meals, teaching craft and gardening skills, preserving etc. The household economy should be upheld as the centre of our lives and the main source of life satisfaction, more important than career.

• Work towards the procedures for making good town decisions about these developments, the referenda, consensus processes, town meetings.

• Throughout all these activities recognise that our primary concern is to raise consciousness regarding the nature, functioning and unacceptability of consumer-capitalist society and the existence of better ways.

One concern the CDC would have is what not to try to do, or not yet. For instance in my view it is not at all clear that in the early states towns should make much effort to produce their own energy. Producing most forms of renewable energy in significant quantities is difficult and costly. Further, its significance for town independence or resilience is questionable. For instance if your town builds a wind farm this will benefit the nation but is not likely to be of much benefit to the town, other than as an export industry (sending surplus electricity to the grid…without which it could not function.) When the wind is down the town would have to draw from the grid.

More significant however would be the effort to reduce energy consumption, as distinct from increase production, by for instance insulating houses, cutting down on unnecessary production, localising work, cutting town imports, increasing local leisure resources and especially increasing local food production. (The Kinsale Energy Descent Plan recognises this.) Town resilience is going to depend more on the capacity to get to work and produce necessities without using much energy, than on whether the town can produce energy.

The introduction of local currencies.

Although the introduction of our own local currency is very important there is much confusion about local currencies and often proposed schemes would not have desirable effects. There is a tendency to proceed as if just creating a local currency would do wonders, without any thinking through of how it is supposed to work. lt will not have desirable effects unless it is carefully designed to do so. I have serious concerns about the currency schemes being adopted by the Transition Towns movement and I do not think the initiatives I am aware of are going to make significant contributions to the achievement of town resilience. It is not evident that they are based on a rationale that makes sense and enables one to see why they will have desirable effects.

It is most important that we are able to see precisely what general effect the form of currency we have opted for is going to have; we must be able to explain why we are implementing it in view of the beneficial effects it designed to have. To me the main purpose in introducing a currency is to contribute to getting the unused productive capacity of the town into action, i.e., stimulating/enabling increase in output to meet needs. (Another purpose is to avoid the interest charges when normal money is borrowed, but this can’t be done unless the new money is to be used to pay for inputs available in the town; it can’t pay for imported cement for instance.)

Following is the strategy that I think is most valuable. Consider again what happens in the above scenario, when our CDC sets up a community garden and invites people to come and work in it. When time contributions are recorded with the intention of sharing produce later in proportion to contributions, these slips of paper function like an IOU or “promissory note” (although that’s not what they are.). They can be used to “buy” garden produce when it becomes available. They are a form of money which enables everyone to keep track of how much work, producing and providing they have done and how great a claim they have on what’s been produced. The extremely important point about the design and use of this currency is that it helps in getting those idle people into producing to meet some of their own needs. Obviously the introduction of the currency was not the most important element in the process; organising the “firm” was the key factor. Also obvious is the way the currency works; you can see what its desirable effects are. So just introducing a currency of some kind does not necessarily have any desirable effect and it is crucial to do it in a way that you know will have definite and valuable effects.

At a later stage we can use our currency to start trading with firms in the old economy. We can find restaurants for instance willing to sell us meals which we can pay for with our money. They will accept payment in our money if they can then spend that money buying vegetables and labour from us in Economy B. But note that the normal shops in the town cannot accept our money and we in Economy B cannot buy from them, unless there is something we can sell to them. They can’t sell things to us, accepting our money, unless they can use that money. Nothing significant can be achieved unless people acquire the capacity to produce and sell things that others want. So the crucial task here for the Community Development co-op look for things we in Economy B might sell to the normal firms in the town.

Councils can facilitate this process, for example by accepting our new money in part payment of their rates—but again only if there is something they can spend the money on, that is, goods and services they need that we in Economy B can provide. Therefore the CDC must look for these possibilities.

Sometimes it makes sense for a council to issue a currency to enable use of local resources, especially labour, to build an infrastructure without having to borrow and pay interest to external banks. This can only be done for those inputs that are available locally. If for instance the cement for the swimming pool has to be imported then it will have to be paid for in national currency, but it would be a mistake to borrow normal money to pay the workers if they are available in the town. They can be paid in specially printed new money with which they are able to pay (part of) their rates. Note however that the council then has the problem of what to do with these payments. If it burns them the council has actually paid for the pool via reduced normal money rate income, and will have to reduce services to the town accordingly. Better to keep the money perpetually in use within a new Economy B, so those workers and the council can go on providing things to each other.

Now consider some ways of introducing a new currency that will not have desirable effects.

What would happen if the council or a charity just gave a lot of new money to poor people, and got some shops to agree to accept it as payment for goods they sell? The recipients would soon spend it…and be without jobs and poor again. The shops would hold lots of new money…but not be able to spend it buying anything they need. (They could use it to buy from each other, but would have no need to do this, because they were already able to buy the few things they needed from each other using normal money.) Again if things are not to gum up it must be possible for the shopkeepers in the old economy to use their new money purchasing something from those poor people, and that’s not possible unless they can produce things within a new Economy B.

Sometimes the arrangement is for people to buy new notes using normal money. This is just substituting, and achieves nothing for the town economy. What’s the point of people who would have used dollars now buying using “eco”s they have bought? Again there is no effect of bringing unused productive capacity into action.

What about the argument that local currencies encourage local purchasing because they can’t be spent outside the town? This reveals confusion. Anyone who understands the importance of buying local will do so as much as they can, regardless of what currency they have. Anyone who doesn’t will buy what’s cheapest, which is typically an imported item. Obviously what matters here is getting people to understand why it’s important to buy local; just issuing a local currency will make no significant difference.

Similarly, currencies which depreciate with time miss the point and are unnecessary. Anyone who understands the situation does not need to be penalised for holding new money and not spending it. In any case it’s wrong-headed to set out to encourage spending; people should buy as little as they can, and any economy in which you feel an obligation to spend to make work for someone else is not an acceptable economy. In a sensible economy there is only enough work, producing and spending and use of money as is necessary to ensure all have sufficient for a good quality of life.

Conclusion

The TransitionTowns movement is characterised by a remarkable level of enthusiasm and energy. I think this reflects the long pent up disenchantment with consomer-capitalist society and a desire for something better. There is a powerful case that the only way out of the alarming global predicament we are in has to be via a Transition Towns movement of some kind. To our great good fortune one has burst on the scene. But I worry that it could very easily fail to make a significant difference. My hope is that the foregoing thoughts will help to ensure that it does become the means whereby we get through to a sustainable and just world.

Appendix: An indication of the limits to growth case re the global

situation.

Consider some basic aspects of our situation. I have detailed this case in several sources including http://ssis.arts.unsw.edu.au/tsw/ and will only refer here to a few of the main themes.

• If all the estimated 9 billion people likely to be living on earth after 2050 were to consume resources at the present per capita rate in rich countries, world annual resource production rates would have to be about 8 times as great as they are now.

• It is now widely thought that global petroleum supply will peak within a decade, and be down to half the present level by about 2030.

• “Footprint analysis” indicates that the amount of productive land required to provide one person in Australia with food, water, energy and settlement area is about 7- 8 ha. The US figure is closer to 12 ha. If 9 billion people were to live as Australians do, approximately 70 billion ha of productive land would be required. However the total amount available on the planet is only in the region of 8 billion ha. In other words our rich world footprint is about 10 times as big as it will ever be possible for all people to have.

• It is increasingly being thought that in order to prevent dangerous increase in global warming all CO2 emissions will have to be totally eliminated by 2050. There are good reasons for concluding that this is not possible in a consumer society, firstly because the alternative energy sources such as the sun and wind cannot meet demand, (Trainer, 2008) and even if they could there isn’t time to do so.

The point which such figures makes glaringly obvious is that it is totally impossible for all to have the ”living standards” we have taken for granted in rich countries like Australia. We are not just a little beyond sustainable levels of resource demand and ecological impact – we are far beyond sustainable levels.

However the main worry is not the present levels of resource use and ecological impact discussed above, it is the levels we will rise to given the obsession with constantly increasing volumes of production. The supreme goal in all countries is to raise incomes, “living standards” and the GDP as much as possible, constantly and without any idea of a limit. That is, the most important goal is economic growth.

If we assume a) a 3% p.a. economic growth, b) a population of 9 billion, c) all the world’s people rising to the “living standards” we in the rich world would have in 2070 given 3% growth until then, the total volume of world economic output would be 60 times as great as it is now.

So even though the present levels of production and consumption are grossly unsustainable the determination to have continual increase in income and economic output will multiply these towards absurdly impossible levels in coming decades.

Such enormous multiples rule out any possibility that technical advance can enable us to continue the pursuit of growth and affluence while greater energy efficiency, recycling effort, pollution control etc. deals with the resulting resource and ecological impacts.

The second major fault built into our society is that its economic system is massively unjust. We in rich countries could not have anywhere near our present “living standards” if we were not taking far more than our fair share of world resources. Our per capita consumption of items such as petroleum is around 17 times that of the poorest half of the world’s people. The rich 1/5 of the world’s people are consuming around 3/4 of the resources produced. Many people get so little that 800 million are hungry and more than that number have dangerously dirty water to drink. Three billion live on $2 per day or less.

This grotesque injustice is primarily due to the fact that the global economy operates on market principles. In a market need is totally irrelevant and is ignored. Resources and goods go mostly to those who are richer, because they can offer to pay more for them. Thus we in rich countries get almost all of the scarce oil and timber traded, while billions of people in desperate need get none.

Even more importantly, the market system explains why Third World development is so very inappropriate to the needs of Third World people. What is developed is not what is needed; it is always what will make most profit for the few people with capital to invest. Thus there is development of export plantations and cosmetic factories but not development of farms and firms in which poor people can produce for themselves the things they need. Many countries such as Haiti get no development at all because it does not suit anyone with capital to develop anything there…even though they have the land, water, talent and labour to produce most of the things they need for a good quality of life.

These are some of the reasons why conventional development can be regarded as a form of plunder. The Third World has been developed into a state whereby its land and labour benefit the rich, not Third World people. Rich world “living standards” could not be anywhere near as high as they are if the global economy was just.

These considerations of sustainability and global economic justice show that our predicament is extreme and cannot be solved in consumer-capitalist society. The problems are caused by some of the fundamental structures and processes of this society. There is no possibility of having an ecologically sustainable, just, peaceful and morally satisfactory society if we allow market forces and the profit motive to be the major determinant of what happens, or if we seek economic growth and ever-higher “living standards” without limit. Many people who claim to be concerned about the fate of the planet refuse to face up to the fact that this society cannot be fixed. The problems can only be solved by vast and radical change to some very different systems.

Ted Trainer

18.5.09

Recent comments