"The Victorian government appears to be bent on creating ‘rent-seeking’ opportunities for construction companies and financial institutions rather than meeting the transport needs of the community." (Kenneth Davidson) The following article is the text of a speech given by Kenneth Davidson at the Protectors of Public Lands Victoria AGM 10 May 2014 (Emphases and heading by candobetter.net editor.)

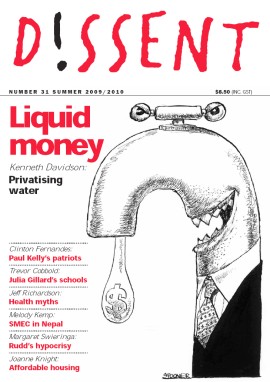

"The Victorian government appears to be bent on creating ‘rent-seeking’ opportunities for construction companies and financial institutions rather than meeting the transport needs of the community." (Kenneth Davidson) The following article is the text of a speech given by Kenneth Davidson at the Protectors of Public Lands Victoria AGM 10 May 2014 (Emphases and heading by candobetter.net editor.) The last time I spoke to Protectors of Public Lands Victoria at the AGM in 2011 I made the subject of my talk ‘how PPPs can make you sick as well as poor’. I looked at the financing costs of building three hospitals – The Royal Children’s Hospital, the Royal Women’s Hospital and Bendigo General Hospital - and the difference between funding exactly the same hospitals, using exactly the same architects and builders but financing them with government debt rather than as a PPP would save the Victorian taxpayer $90 million a year or $3.5 billion over the 25 year life of the PPPs.

The last time I spoke to Protectors of Public Lands Victoria at the AGM in 2011 I made the subject of my talk ‘how PPPs can make you sick as well as poor’. I looked at the financing costs of building three hospitals – The Royal Children’s Hospital, the Royal Women’s Hospital and Bendigo General Hospital - and the difference between funding exactly the same hospitals, using exactly the same architects and builders but financing them with government debt rather than as a PPP would save the Victorian taxpayer $90 million a year or $3.5 billion over the 25 year life of the PPPs.

Those figures were based on official interest rates of 5.5 per cent. The cost would be even higher today when the state government could use its AAA rating to borrow at 3.6 per cent. I pointed out the $90 million in unnecessary payments compared to government borrowings would be sufficient to pay a salary increase to public hospital nurses an additional $3,000 a year – a 5 per cent increase. This is far better than chiselling their conditions and undermining hospital safety by increasing patient ratios and replacing professional nurses with nurse assistants in the name of productivity offsets.

When you multiply these sort of deals through the financing of government schools, the desalination plant, Southern Cross (Spencer Street) Station and roads and now prisons, rail links, rail corridors and Metro Rail Link (redesigned without a business case to facilitate Crown Casino and a new real estate development at Fisherman’s Bend), you are beginning to talk real money.

According to the budget papers, PPPs, listed under long-term borrowings as finance lease liabilities, now total $7.8 billion. The interest expense on these leases, listed as finance charges on finance leases, total $770 million. This is equal to an interest expense of just under 10 per cent.

In money terms this amounts to about $500 million or half a billion a year more than if the leases had been financed by the issue of state government bonds, currently yielding 3.6 per cent interest.

Neoliberal mythology

The banks and superannuation funds which profit from investing in PPPs rather than public debt promote the neoliberal mythology that governments can’t ‘afford’ debt, even though there are numerous examples of social and economic infrastructure which can yield returns well in excess of the cost of borrowing.

In their own businesses, if directors took the same approach to financial management as they demand from government, to minimise debt to the point where they were missing out on profitable investments, the directors and senior managers would be threatened with dismissal for running a ‘lazy balance sheet’ either through a takeover or shareholder revolt.

But, in Australia the politicians who facilitate the PPP industry are seen generally as wise leaders whose financial rectitude, while promoting ‘tough’ decisions, is in the public interest.

The former Member for Melbourne and Finance minister in the Rudd government, together with former Labor Prime Minister, Paul Keating, are senior financial advisors with the investment bank, Lazard.

When Tanner joined the bank shortly after the 2010 election his job description included working on how to improve the PPP tender process. Lazard has already made one submission to the Victorian government offering to manage the PPP process for both sections of the East West Link Project last year. The proposal was rejected.

The peak industry lobby for the PPP industry, Infrastructure Partnerships Australia, sponsored a conference in March 2012 at the Crown Casino on the subject “user pays, exploring the myths of free infrastructure”. As could be expected the conference wasn’t about the cheapest and most effective ways of financing infrastructure, but how to make PPPs risk free to the private investors to avoid recent losses, particularly involving toll roads.

Tanner was the Keynote speaker. He said that there have to be more innovative ways of financing PPPs to restore confidence in the PPP vehicle following the success of the City Link. He gave the example of the Peninsular Link which substituted an “availability charge” yielding an assured 11.5 per cent for tolls because there was no way the $760 million investment could be sustained on tolls given the likely traffic volumes.

His citing these two examples of successful PPPs makes it clear that the proponents of PPPs are primarily interested in a contract which guarantees a stream of earnings over two to three decades at interest rates two to three times the long-term bond rate without any risk to the proponents.

The background to these successful examples of the PPP method of financing infrastructure shows that PPPs amount to rorts.

It is a moot point whether City Link should have been built. A rail connection to the airport could have provided greater benefit to Melbourne at a fraction of the cost. In terms of passenger numbers Tullamarine Airport is the biggest in the world without a rail link to the city.

Toll charges are at least three times the level which would be needed if the road had been funded by government debt. City Link is one of the most profitable toll roads in the world. In 2012-13 City Link toll revenue totalled $499 million. The operator, Transurban, is allowed to increase toll rates by 4.5 per cent a year or the inflation rate, whichever is the greater. The toll growth compounds at a greater rate than inflation so that a Tulla 24 hour pass is 110 per cent higher now than when the tollway opened in 2000.

The project cost was $1.8 billion but $600 million was mainly capital costs associated with the PPP. For instance $171 million was allocated to Equity Infrastructure Bond distributions during the construction phase before one car had passed under a transponder. Another $350 million was allocated to items such as Consultancy and Sponsor Recovery Costs, Corporate Overheads and Marketing (during construction), and Capitalised Interest Expense.

The Design and Construction Contract was $1.2 billion. This is the main cost which would have been associated with the building of exactly the same road, using the same designers and construction contractors, if City Link had been let out to public tender and financed by public borrowings at the long-term bond rate.

The gross return of $499 million in 2012-13 on $1.2 billion is about 42 per cent. On the assumption that operating expenses, maintenance and taxes more than halved the gross return to 20 per cent, this is still five times the return from tolls needed to fund public borrowings at 4 per cent.

In 1999, Alan Stockdale, Treasurer at the time of City Link negotiations, later announced his retirement from Parliament and his intention to join Macquarie bank as the chairman of the bank’s asset and infrastructure group after the election but before he handed in his commission as Treasurer to the Victorian Governor.

The Australian Financial Review (7th October 1999) said: “As a non-executive director, he was likely to receive a remuneration package in the order of $500,000 a year. Mr Stockdale joins an inner circle of executives at Macquarie whose main role has been described in the banking fraternity as to essentially ‘meet and greet’.”

But PPPs became on the nose after a spate of infrastructure projects financed as PPPs in Queensland, NSW and in Victoria’s case, the EastLink, failed to live up to the optimistic forecasts of toll revenues and investors in the Connect East franchise (set up to build, own and operate EastLink) lost money.

In order to restore investor confidence in these vehicles, the main rationale for the higher returns on PPPs compared to the cost of financing infrastructure with government debt, namely that the ‘risk’ would be transferred from the taxpayer to the private partners, was turned on its head.

The Peninsular Link PPP was developed in the wake of the failure of the EastLink to meet its traffic projections. EastLink was the road from nowhere to nowhere.

It was clear only months after EastLink began operations that the franchise was dying under its burden of debt. Hence the urgency to connect EastLink up to additional traffic to keep its backers from pulling the plug, as had occurred with toll roads financed as PPPs in Sydney and Brisbane. The banks refused to finance the construction of the bypass unless the risk was transferred from the private partners to the government.

Instead of the PPP revenue being derived from tolls it was decided the revenue would be paid by the government via an ‘availability charge’ This meant that providing the Peninsula Link is fit for purpose - i.e. it is maintained in a condition sufficient to carry the volume of traffic for which is was designed - an ‘availability’ payment of $92 million a year will be paid over the 25 years of the franchise, irrespective of how many vehicles use the freeway. It is equivalent to a return of 11.7 per cent on the $760 million cost to build the bypass.

The reader might ask why the government did not borrow the money itself at the long-term bond rate, which was about 5 per cent at the time the road was built and saved $54 million a year or $1.4 billion over the 25 year life of the PPP. The savings would have been sufficient to finance borrowings of $800 million, sufficient to build a public hospital or finance 5,000 elective surgery operations in public hospitals.

But there’s more. The capital cost of $760 million of the four lane tollway, mainly over flat reserve land, works out at $28 million a km. The Abigroup built the Peninsular link. The Abigroup also built 41 km four-lane Geelong Bypass freeway for $19 million per km and it includes a railway station and 100 metre bridge over the Barwon River involving major earthworks. The construction cost of the Peninsula Link is 67 per cent more expensive per km than the Geelong Bypass. Why?

The reason is the Commonwealth put up most of the money for the Geelong Bypass. It refused to put up money for the Peninsular Link because it couldn’t pass a Benefit Cost test required by Infrastructure Australia. As the Commonwealth put up the money for the Geelong Bypass, it ensured it got value for money.

The Victorian government appears to be bent on creating ‘rent-seeking’ opportunities for construction companies and financial institutions rather than meeting the transport needs of the community.

The Mornington Peninsula and the Hastings area are public transport deprived and both the catchment areas include some of the poorest households in Greater Melbourne with acute, unmet public transport needs. But there is already a further study extending the road capacity to relieve congestion on Point Nepean Road completed in 2013 with no consideration of mode shift to public or active transport. Remember, the Peninsular Link was set up by a Labor government.

'Sovereign risk'

Labor has not changed its spots in opposition. In a desperate attempt to win back the Melbourne seat from the Greens it promised to oppose the EWL but it would not refinance the debt because it would create ‘sovereign risk’. Garbage! There is no difference between a government refinancing debt to take advantage of lower interest rates than a mortgagor taking advantage of lower interest rates to refinance the house mortgage.

The major parties were as one in refusing to consider refinancing the AquaSure desalination PPP contract on the grounds of ‘Sovereign risk’.

To add insult to injury, Aquasure received permission from the government to renegotiate the debt for its own interests. It has taken advantage of the lower rates to increase its own profits.

Shadow Treasurer, Tim Pallas, has since backed down in the face of the talk by adjunct professor of Law at the ANU College of Law and author of a standard text on government contracts, who pointed out anybody, including governments, can break contracts subject to damages.

The cost of damages would be miniscule compared to the cost of going ahead with an EWL PPP, especially if the Labor opposition made its intentions clear before any contract is signed so that the private partners would know the risks before entering into the contract.

Protectors of Public Lands say that notice has been received that the “Greens” Mayor Samantha Ratnam will, tomorrow at 4:30 pm, preside over a “Sod-Turning Ceremony” to mark the start of construction of a monster Moreland Council-funded community/medical centre on Rogers Memorial Reserve in Pascoe Vale. If you can come to the "sod turning ceremony" we will be having a silent vigil of protest. Bring a sign. Come to the Rogers Memorial Reserve on Prospect Street (off Cumberland Road) in the parking area near the Pascoe Vale Swimming Pool. Melways Page 17 A8.

Protectors of Public Lands say that notice has been received that the “Greens” Mayor Samantha Ratnam will, tomorrow at 4:30 pm, preside over a “Sod-Turning Ceremony” to mark the start of construction of a monster Moreland Council-funded community/medical centre on Rogers Memorial Reserve in Pascoe Vale. If you can come to the "sod turning ceremony" we will be having a silent vigil of protest. Bring a sign. Come to the Rogers Memorial Reserve on Prospect Street (off Cumberland Road) in the parking area near the Pascoe Vale Swimming Pool. Melways Page 17 A8.

"The Victorian government appears to be bent on creating ‘rent-seeking’ opportunities for construction companies and financial institutions rather than meeting the transport needs of the community." (Kenneth Davidson) The following article is the text of a speech given by Kenneth Davidson at the Protectors of Public Lands Victoria AGM 10 May 2014 (Emphases and heading by candobetter.net editor.)

"The Victorian government appears to be bent on creating ‘rent-seeking’ opportunities for construction companies and financial institutions rather than meeting the transport needs of the community." (Kenneth Davidson) The following article is the text of a speech given by Kenneth Davidson at the Protectors of Public Lands Victoria AGM 10 May 2014 (Emphases and heading by candobetter.net editor.) The last time I spoke to Protectors of Public Lands Victoria at the AGM in 2011 I made the subject of my talk ‘how PPPs can make you sick as well as poor’. I looked at the financing costs of building three hospitals – The Royal Children’s Hospital, the Royal Women’s Hospital and Bendigo General Hospital - and the difference between funding exactly the same hospitals, using exactly the same architects and builders but financing them with government debt rather than as a PPP would save the Victorian taxpayer $90 million a year or $3.5 billion over the 25 year life of the PPPs.

The last time I spoke to Protectors of Public Lands Victoria at the AGM in 2011 I made the subject of my talk ‘how PPPs can make you sick as well as poor’. I looked at the financing costs of building three hospitals – The Royal Children’s Hospital, the Royal Women’s Hospital and Bendigo General Hospital - and the difference between funding exactly the same hospitals, using exactly the same architects and builders but financing them with government debt rather than as a PPP would save the Victorian taxpayer $90 million a year or $3.5 billion over the 25 year life of the PPPs. The consideration of the Planning Zones Review should have been referred to the Parliamentary Committee for Environment and Planning which has considerable resources to put the 2,000 submissions on the Parliamentary website and then record on Hansard the hearings of some of the submitters before the Parliamentary Committee.

The consideration of the Planning Zones Review should have been referred to the Parliamentary Committee for Environment and Planning which has considerable resources to put the 2,000 submissions on the Parliamentary website and then record on Hansard the hearings of some of the submitters before the Parliamentary Committee.

In her submission to the Victorian State Department of Planning and Community Services, Julianne Bell, Secretary of

In her submission to the Victorian State Department of Planning and Community Services, Julianne Bell, Secretary of

Threats to Royal Park: East West link, Children's Hospital expansion onto public land under Royal Children’s Hospital (Land) Act 2007, large new obtrusive metal public toilet known as "Doyle's dunny" after the Lord Mayor prioritised its installation. Meaningful community events planned to combat proposed outrages. Turn up to meet an energetic and politicised crew of public land activists with a taste for local environment and democracy.

Threats to Royal Park: East West link, Children's Hospital expansion onto public land under Royal Children’s Hospital (Land) Act 2007, large new obtrusive metal public toilet known as "Doyle's dunny" after the Lord Mayor prioritised its installation. Meaningful community events planned to combat proposed outrages. Turn up to meet an energetic and politicised crew of public land activists with a taste for local environment and democracy.

Good news! The Federal Budget did not provide funds to Premier Baillieu for the East West Link. Julianne Bell thanks those 16 community groups for supporting PPL VIC and the Royal Park Protection Group for Ian Hundley's and her mission to Canberra on 27 March 2012 to present their submission to Infrastructure Minister Albanese in which they requested the Federal Government NOT fund the EW Link but support public transport projects. Ian Hundley and Julianne briefed staff. Thanks also go to the Greens "for their principled stand against the East West Link and for their advocacy for Doncaster Rail Link."

Good news! The Federal Budget did not provide funds to Premier Baillieu for the East West Link. Julianne Bell thanks those 16 community groups for supporting PPL VIC and the Royal Park Protection Group for Ian Hundley's and her mission to Canberra on 27 March 2012 to present their submission to Infrastructure Minister Albanese in which they requested the Federal Government NOT fund the EW Link but support public transport projects. Ian Hundley and Julianne briefed staff. Thanks also go to the Greens "for their principled stand against the East West Link and for their advocacy for Doncaster Rail Link."

Call for Victorians to write to the Hon. Anthony Albanese, Minister for Infrastructure and Transport at A.Albanese, to oppose funding of the East West Link and to support funding public transport instead, especially the Doncaster Rail Link along the Eastern Freeway.

Call for Victorians to write to the Hon. Anthony Albanese, Minister for Infrastructure and Transport at A.Albanese, to oppose funding of the East West Link and to support funding public transport instead, especially the Doncaster Rail Link along the Eastern Freeway.

The guest speaker at the AGM will be Kelvin Thomson, Federal Member of Parliament for Wills and advocate of sustainable population. He will speak on: "A bigger Melbourne is not a better Melbourne”. All are very welcome to the meeting.

The guest speaker at the AGM will be Kelvin Thomson, Federal Member of Parliament for Wills and advocate of sustainable population. He will speak on: "A bigger Melbourne is not a better Melbourne”. All are very welcome to the meeting.

This threat to clearfell half of Melbourne's street and park trees because they are supposedly "nearing the end of their lives" is an unprecedented threat to Melbourne's heritage. I regard the threat to Melbourne's trees as one of greatest threats to Melbourne and its livability. Plus the revival of the East West Link tollway-in-a-tunnel through the inner suburbs and parks. Can you imagine what this tree clearance of elms and plane trees will do to tourism? And what about living conditions in the city - the "heat island effect" will be extraordinary if half the city's trees are to be removed. Just as they are looking fantastic with recent good rainfall! - Julianne Bell, Protectors of Public Lands Victoria

This threat to clearfell half of Melbourne's street and park trees because they are supposedly "nearing the end of their lives" is an unprecedented threat to Melbourne's heritage. I regard the threat to Melbourne's trees as one of greatest threats to Melbourne and its livability. Plus the revival of the East West Link tollway-in-a-tunnel through the inner suburbs and parks. Can you imagine what this tree clearance of elms and plane trees will do to tourism? And what about living conditions in the city - the "heat island effect" will be extraordinary if half the city's trees are to be removed. Just as they are looking fantastic with recent good rainfall! - Julianne Bell, Protectors of Public Lands Victoria

Overspending Brimbank City Council is trying to sell off 14 - yes, fourteen- parks and open space against the reasonable objections of Brimbank Residents, who they are supposed to serve. Have you ever heard the like? How dare they? If other Victorian fail to stand up to support the residents of Brimbank on this, such processes could be normalised - and we will all be living in a concrete wasteland, not just Brimbank residents. For some history of Brimbank profligacy and corruption, see "

Overspending Brimbank City Council is trying to sell off 14 - yes, fourteen- parks and open space against the reasonable objections of Brimbank Residents, who they are supposed to serve. Have you ever heard the like? How dare they? If other Victorian fail to stand up to support the residents of Brimbank on this, such processes could be normalised - and we will all be living in a concrete wasteland, not just Brimbank residents. For some history of Brimbank profligacy and corruption, see "

Boroondara Council has proposed development of 48 “Neighbourhood Activity Centres” (NAC’s) over, on and around strip shopping centres or villages throughout the municipality of Boroondara. This is a fatally flawed policy having been developed before the last election and is based on the Brumby Government’s Housing Capacity Strategy under which each metropolitan Council was given a target population figure to accommodate. The new Coalition Government has renounced this policy and has scrapped the Brumby blueprints - Melbourne 2030 and Melbourne @ 5 million. Boroondara Council is proceeding regardless.

Boroondara Council has proposed development of 48 “Neighbourhood Activity Centres” (NAC’s) over, on and around strip shopping centres or villages throughout the municipality of Boroondara. This is a fatally flawed policy having been developed before the last election and is based on the Brumby Government’s Housing Capacity Strategy under which each metropolitan Council was given a target population figure to accommodate. The new Coalition Government has renounced this policy and has scrapped the Brumby blueprints - Melbourne 2030 and Melbourne @ 5 million. Boroondara Council is proceeding regardless.

When the Standing Committee on Finance and Public Administration hearing convened to hear from Peta Duke on 12 March 2010, she did not attend in answer to the summons. She had written the notorious Media Plan proposing a sham public consultation process to earn favour with the electorate. Mr Madden, who had not been summoned, sat in the chair reserved for the witness – his former Ministerial adviser - and said that he would answer questions. This was a blatant attempt to take over the inquiry being carried out by Parliament into his office’s conduct. - Protectors of Public Lands (Victoria)

When the Standing Committee on Finance and Public Administration hearing convened to hear from Peta Duke on 12 March 2010, she did not attend in answer to the summons. She had written the notorious Media Plan proposing a sham public consultation process to earn favour with the electorate. Mr Madden, who had not been summoned, sat in the chair reserved for the witness – his former Ministerial adviser - and said that he would answer questions. This was a blatant attempt to take over the inquiry being carried out by Parliament into his office’s conduct. - Protectors of Public Lands (Victoria)

Recent comments