Australia's cultural problem of foreigners outnumbering Australians began back in 1853 when thousands of Chinese rocked up in their droves at the gold field along Victoria's Buckland River in north east Victoria in the 1850s and local violence erupted.

'Following the election of a coalition of the Liberal and Country parties in 1949, Immigration Minister Harold Holt allowed 800 non-European refugees to remain in Australia and Japanese war brides to enter Australia. Over subsequent years, Australian governments gradually dismantled the policy, with the final vestiges being removed in 1973 by the new Labor government.' [Read More].

Where are traditional Australians today? Many are marginalised and have hit underclass status and are victims of substance abuse.

Australians need to call for reform to our Immigration Act and the Australian Citizenship Act to automatically revoke citizenship and deport foreigners invited to our shores but who subsequently commit serious crimes and end up in Australian gaols.

Despite Australia's tolerance, generosity, freedoms, opportunities and its high standard of living, immigrants who go on to commit serious crimes demonstrate that they don't value what Australia has to offer them. Such people seem not to want to integrate with Australians but perpetuate their foreign life here and bring their foreign baggage with them. They have elected to bring their violent past and ethnic troubles with them.

Immigrants to our shores who flout Australian laws forfeit the right to live in Australia. Immigrant criminals downgrade Australian society and are an unwelcome burden.

MEDIA REPORTING OF CRIME BIASED AGAINST AUSTRALIANS

Almost invariably a week does not pass without a news report of some serious criminal activity in each of these cities and almost invariably committed by an immigrant.

Yet the mass media hush the ethnicity for dubious political correctness. However, when the offender is Caucasian Australian or Aboriginal Australian in appearance the media are more than happy to report as such. In the media there is an immigrant bias against Australians. Why? Is it a cultural superiority complex that perceives traditional Australians (those born here and with ancestral heritage here) to be so privileged a demographic as to be accepting of bias against them? Does that same cultural superiority complex permit immigrants to receive special favouritism because they are perceived as the underprivileged?

ANTI-ASSIMILATION POLICY BEHIND AUSTRALIA'S DIVISIVE ETHNIC ENCLAVES

Australia's immigration has concentrated in its capital cities. Why? The standard justification is 'jobs'. Most jobs are in the cities and many of these jobs are in government which at local, state and federal levels has actively encouraged immigrants in employment.

Subsequent immigrant arrivals so too target the cities, naturally preferring the familiarity of their own kind. This is a primitive animal trait that pervades all human cultures. English prefer to be with English, Irish with Irish, Americans with Americans, and if one travels overseas such as to Bali or Thailand or the UK, one will see Australians clustered with other Australians who have preceded them.

But ethnic clustering delays and inhibits integration with the broader traditional local community. It is integration that makes immigration work to the mutual benefit of both the immigrant and the incumbent broader population. Integration works when the local language is actively learned, practiced and adopted; when choice of place to live is outside the comfort of the ethnic enclave; when choice of work is with others outside the same ethnic demographic; when one chooses to send children to an ordinary school, when one actively seeks social and leisure pursuits that engage with the general population.

Idealistic Laboral governments since Whitlam have similarly perpetuated anti-assimilation and so ethnic clustering has exploded to the extent that now whole suburbs are dominated by single by a single ethnic immigrant group, effectively displacing the original inhabitants. It is like British colonisation of early Australia which pushed out the native Aborigines.

This rise of ethnic enclaves continues to have a divisive impact on the cohesiveness of Australia's urban societies between the ethnic groups themselves and between ethnic groups and traditional Australians. The 2005 Cronulla Riots are a case in point.

A WAVE OF IMMIGRANT CRIME SCOURGING URBAN AUSTRALIA

In Australia's innocent early 1970s before Whitlam's Muliculturalism Manifesto of 1972, crime in Australia was very low. Like any developed country although Australia had its share of crime, there were no drive-by shootings, no home invasions, no ethnic violence, no racial rioting, no employment slavery, no honour crimes against women, no criminal doctors, no tit-for-tat homicides between warring families, no gangland murders and even political assassinations!

The wave of such heinous crimes, previously foreign to Australia, were what we only read about happening in gun-toting American and in backward societies in the Middle East, African and Asia. But now those backward violent societies have been allowed to settle and continue their backward violent ways in urban Australia.

Anti-assimilation idealism has turned its back on traditional Australian values and instead encouraged new immigrants to retain their ethnicity and set up their foreign cultures and traditions here. Immigrants have done so and in so doing have had a harder time becoming accepted into Australian society. At the extreme where ethnic culture is clustered enclaves, where they don't speak English, where there is little interaction with the broader Australian community, such immigrants are disadvantaged socially and financially. Youths of immigrants are shunned and disaffected and many out of frustration and boredom turn to petty crime.

A great portion of foreigners (old word for 'immigrant') who commit crimes in Australia habitually have taken up residence in urban Australia, particularly in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth.

South West Sydney for instance has become a ghetto for ethnic violence, drive-by shootings, home invasions, racial rioting, employment slavery, honour crimes against women, criminal doctors, tit-for-tat homicides between warring families, gangland murders and even political assassinations! South West Sydney since Whitam's mass immigration of the 1970s has transformed what was once working class areas of south western Sydney like Cabramatta, Liverpool, Lakemba and Bankstown into ethnic enclaves of violence. At night many males from these areas take to the streets of Sydney's CBD.

In Melbourne, it's the suburbs of the inner west, the north and outer west, where immigrants have clustered and eventually demographically have dominated. Suburbs like Maribyrnong, Broadmeadows, Dallas, Altona, Dandenong, and Springvale.

In Brisbane, the crime suburbs are Fortitude Valley and South Brisbane,;while in the south Beenleigh, Woodridge, Upper Mount Gravatt, Annerley, Browns Plains, Kingston, and Loganlea; in the south-west Goodna, Inala, Wacol and Redbank Plains; Aspley in the north, and Wynnum and Alexandra Hills in the east. [Wikipedia]

In Perth, the ethnic crime enclaves are Mirrabooka [Read about Somali crime wave], Balga, Bayswater, Beechboro, Kingsley and a good deal of Perth's northern sprawl suburbia.

Australia's state police forces are overwhelmed.

In New South Wales in 2005 there were '21 murders in 37 days: homicide police overwhelmed' [by John Kidman, Eamonn Duff and Erin O'Dwyer in Sydney Morning Herald, 12th February 2006] which made it "the worst new year on record"

'Homicide squad investigators are unable to cope, forcing the recruitment of officers normally assigned exclusively to unsolved cases.'

While the NSW Police Association believes about 3000 extra officers are needed statewide on any given day, as many as one in four top detectives are unavailable to investigate major sexual assaults, major robberies, drug deals and fraud cases.'

"There are armed hold-ups, rapes, homicides and extortions going on and we're being forced to cut back on the vital work of dealing with them."

CASES IN POINT

Drive-by Shootings

1st September 2010 - Drive-by Shootings in Merrylands

'Woman injured in drive-by shooting' [The Daily Telegraph]

'A WOMAN suffered wounds to her head after shots were fired into a house in Sydney's west last night.

The woman, 40, was in a bedroom of a house in Desmond St, Merrylands West when it was peppered with bullets about 11.25pm.

A police spokeswoman said the woman suffered "superficial" wounds to her head but they were unable to say if it was from a projectile or flying shrapnel.'

If the culprits were immigrants - deport them to from whence they came!

'Sydney erupts with 3 shootings in 6 hours' by Chelsea White, Daily Telegraph, 2nd August 2010.

'A YOUNG man is dead and two others injured after a spate of shootings across Sydney yesterday.

A man, believed in his late twenties, was gunned down in broad daylight in a suburban park in Greenacre.

The man was shot several times under a picnic shelter in Roberts Park, near Waterloo and Napoleon Streets at 4.20pm.'

'Drive-by shooting in Sydney park' - August 28, 2010, AAP.

'A man has been shot in the leg in a drive-by shooting in a park in Sydney's west.

Witnesses told police the man was with a group in a park in Warwick Farm about 3.40am (AEST) today when a number of cars drove past and a shot was fired from one of them.'

'Drive-by shooting in Kingsley(Perth) by Lee Rondganger, The West Australian, 11th April 2010.

'Police are investigating the possibility that a drive-by shooting at a house in Kingsley last night was gang related.

A gunman opened fire at a house in Dalmain Street shortly after 9pm. The house was hit by bullets four times.

Police spokesman, Insp. Bill Munee said the attack was targeted and it was not a random shooting. It is believed the incident is related to a fight that occurred a few weeks ago between two groups.'

Home invasions

'Victim critical after Sydney home invasion by Georgina Robinson, 2nd July 2010.

'A man is fighting for life in hospital after having his wrists and ankles slashed during a terrifying home invasion in Sydney’s south-west last night.

The 25-year-old was at home with his girlfriend, mother and stepfather when four men armed with a machete, an axe and a knife burst into the family's Clingan Avenue, Lurnea, house about 11.45pm, police said.'

'Three men invade home in Sydney's west BigPond News, 26th October 2010.

'Three men forced their way into a home in Sydney's south west and demanded money from the occupants.

Police are investigating the home invasion which happened at 8.30pm (AEDT) on Monday at Lime Street in Cabramatta. One of the men, who was armed with a shotgun, confronted a 25-year-old man, a woman aged 20, a three-year-old girl and a three-month-old girl, police said on Tuesday.'

'Machete brandished in Perth home invasion by AAP, 29th October 2010.

'Police are searching for a man and a woman after a home invasion in Perth in which a machete was brandished and a man assaulted. The incident happened around 2am (WST) in the northern suburb of Ocean Reef, police said.

A young woman phoned police to say her stepfather was being beaten up but the offenders had fled by the time police arrived, a spokesman said.

The young woman received a cut during the incident but neither occupants of the house were badly injured and nothing was taken, he said.

In another incident around 5am in the southern suburb of Maddington a woman going to work at a Coles store was approached by two men who demanded she hand over her car keys.

She was grabbed by the neck but fought back and escaped into the store where she set off the alarm, the police spokesman said.

Police are seeking two dark-skinned men of thin build.'

Somalis again...?

Ethnic violence

'Australian Open explodes into ethnic violence by Terry Brown, Herald Sun 24th January 2009.

'A young woman was knocked out by a flying chair as the Australian Open again exploded into ethnic violence yesterday. Chairs were hurled around busy Garden Square and punches were thrown in the latest ugly incident.

Police believe the woman was an innocent bystander caught in the crossfire when tensions between groups of Bosnian and Serb men and teenagers boiled over. The groups had been watching Serb Novak Djokovic beat Bosnian American Amer Delic in a tight four-set match, and baiting each other. Witnesses said the trouble started about 4pm when a drink was thrown....The stoush is the second involving Bosnian supporters this week.

'

'< href="http://www.abc.net.au/lateline/stories/s351038.htm">Ethnic crime under Sydney scrutiny on late night news & current affairs TV programme hosted by Tony Jones on the ABC, 22nd August 2001.

'TONY JONES: Tomorrow, four young men will be sentenced over a gang rape which has ignited an explosive race debate in Sydney. There are claims that a group of men of Lebanese ancestry from the suburb of Bankstown, has targeted Caucasian women to rape.It is a community crisis which some say has been exaggerated.

LYNNE MINION: Reports of Lebanese men preying on young Caucasian women, gang-raping them in planned, horrific attacks, has caused an outcry, leading all the way to the highest levels.

BOB CARR, NSW PREMIER: They are criminals, they are committing criminal acts, they can't blame the ethnic community they come from, and they can't blame the Australian society, I won't accept that.

LYNNE MINION: The NSW Police Commissioner agrees, saying: "this is the largest immigrant population of (mixed) races in the world. It's going to be extraordinarily difficult to settle that melting pot down."

The scene of the crime, the melting pot of Sydney's Bankstown, is at boiling point now, with Caucasians responding.

Violence against the Middle Eastern community is skyrocketing and there have been threats of retaliatory rapes.

HELEN WESTWOOD, BANKSTOWN COUNCILLOR: Some women have reported being spat at, and having derogatory comments made towards them, and abusive comments and obviously that's because Islamic women are very easily identified because of their clothing.

LYNNE MINION: The Lebanese community is calling for calm, saying ethnicity does not predispose an individual to gang-rape, society does.

PHILLIP RIZK, AUSTRALIAN LEBANESE ASSOCIATION: Put them away for good, regardless of what nationality they came from.

I don't believe that plays any part whatsoever. It's the product of Australian society, the streets of Sydney. No more, no less.

LYNNE MINION: The Ethnic Communities Council says it's a political issue which dispels the image of an harmonious multicultural Australia, replacing it with an image of a society of different races -- and other ones are easy to blame.

SALVATORE SCEVOLA, ETHNIC COMMUNITIES COUNCIL: It's becoming prolific in society, this sort of behaviour, This sort of mentality is settling into the minds of Australians to the extent where they are being suspicious of their fellow Australian.

LYNNE MINION: The NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics has weighed into the story, releasing details saying 70 sexual offences were committed in Bankstown in 1999, but they were the work of one man.

One gang-rape has occurred in the Bankstown area this year, and in 2000, it rated below the State average for sexual assault.

The deepening concern on the streets of Sydney has lead to the police spokesperson on sexual assault appearing at odds with her boss.

CMDR LOLA SCOTT, NSW POLICE SERVICE: If we're naive or someone's out there thinking that it only will occur if you live in a particular area, that's putting other women at risk.

LYNNE MINION: Those who work with the victims say that politicising this issue has missed the point -- that 17 per cent of all sexual assaults are gang-rapes and we need to stop it -- society-wide.

JULIE BLYTHE, SEXUAL ASSAULT COUNSELLOR: Perpetrators come from all racial groups, all socioeconomic groups, class, culture, quite across the board.

LYNNE MINION: The one certainty in south-west Sydney, at least, is that the anger and fear generated by the gang-rape reports have triggered a vicious chain-reaction that looks set to go on and on, as will the trauma of the victims of the rapes themselves.

Lynn Minion, Lateline.'

Racial rioting

'2005 Cronulla riots

Employment slavery

Foreign students exploited as slaves by

Nick O'Malley, Heath Gilmore and Erik Jensen of Sydney Morning Herald, 15th July 2009.

'Thousands of overseas students are being made to work free - or even to pay to work - by businesses exploiting loopholes in immigration and education laws in what experts describe as a system of economic slavery.

The vast pool of unpaid labour was created in 2005 when vocational students were required to do 900 hours' work experience. There was no requirement that they be paid.

Overseas students remained bound to the system as completion of such courses became a near-guaranteed pathway to permanent residency.

Since then the number of foreign students enrolled in the vocational training sector has leapt from 65,120 to 173,432 last year - about half of all our overseas students.

The changes have created a $15 billion industry - comparable countries do not offer residency - but experts, teachers and students say many of the private college courses are little more than visa mills. Since 2001 the number of private colleges has leapt from 664 to 4892.

One university-educated overseas student told the Herald she spent $22,000 and two years doing a hairdressing course she will never use, to secure her residency. She did her 900 hours' work experience in a salon linked to the college, where students were required to pay a $1000 non-refundable bond to use the equipment.

Other colleges charge students thousands of dollars in "placement fees" only to advertise their supply of free labour to local business. A black market has sprung up in fraudulent letters of completion.

"If you wanted to make a corrupt system, this is absolutely how you would do it," said an immigration agent, Karl Konrad.'

Other ethnic crimes inflicted upon Australia involve Islamic so-called 'honour' crimes against women, foreign medical doctors committing criminal acts intentionally or negligently against trusting patients, vengeance Killings between warring families, the advent of gangland murders and narcotic drug importation as the following recent case of a Vietnamese on 6th November 2010 highlights:

'41 drug balloons removed from woman's stomach' [ABC, 6th Nov 2010]

If she is found guilty and was born overseas (possibly Vietnam) - deport her!

AUSTRALIAN GAOLS OVERCROWDED WITH IMMIGRANTS

Australian gaols are full and new ones are being built to cope. In 2008, the Alexander Maconochie Centre at Hume cost more than $430,000 per bed, making it the second most expensive prison ever built in Australia.

[,strong>'New prison 'second most expensive' ever built', ABC, 4th March 2008].

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, back in 2003 Australia collectively housed some 23,555 prisoners and at the time the imprisonment rate was 153 prisoners per 100,000 adult population.

[Source: PRISONERS IN AUSTRALIA, ABS CATALOGUE NO. 4517.0, 30 JUNE 2003].

Some insightful statistics are provided by the ABS in the following year, 2004:

* The prisoner population in Australia has increased by more than 40% over the decade to June 2004, which is proportionately higher than the 15% growth in the Australian adult population in the same period.

* The female prisoner population doubled to 1,672 over the decade.

* The male prison population had increased by 40% to 22,499 during the same time.

* Overall, the adult imprisonment rate increased from 127 to 157 prisoners per 100,000 adult population over the period.

* The mean age of prisoners has increased from 31 years to 34 years.

* The proportion of unsentenced prisoners has increased from 12% to 20%.

* The proportion of sentenced prisoners serving an aggregate sentence length of 10 years or more has increased from 10% to 13%.

* Sentenced prisoners with a most serious offence of 'homicide and related offences' increased from 9% to 10% and 'acts intended to cause injury' (including assault) from 11% to 14%.

* At June 2004, there were 24,171 prisoners in Australia, an increase of 3% since 30 June 2003. The median aggregate sentence length was 3.2 years and the median expected time to serve was two years.

* Over 50% of prisoners were males aged 20-34 years.

* Females represented 7% of the total prisoner population.

* Almost 60% of male prisoners and 50% of female prisoners are known to have prior imprisonment.

* Nearly 1 in 2 sentenced prisoners had a most serious offence involving violence or the threat of violence.

[Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, File: '4517.0 - Prisoners in Australia', 23rd December,2004.]

Of the above statistics, three are of most relevance here:

1. The last statistic about the high proportion of prisoners having committed a violent offence

2. The fact that the published prison statistics available from the ABS is six years old (2004)

3. The fact that ethnicity or demography is conspicuous by its absence.

So how many immigrants make up Australia's gaols?

Australian and State governments in their politically correct guise refuse to disclose this statistic. Why? Is it because the proportion is so high as to shock Australian society and likely spark ethnic tension?

WHAT IS THE FULL COST OF IMMIGRATION ON SOCIETY?

Immigration costs local society - processing, financial support, preferential selection of immigrants in government agencies, demand driving costs of living such as inner urban rents and residential property prices, congestion of public services, infrastructure congestion (roads, public transport, hospitals, schools, childcare), cost pressures on utilities - water, electricity, gas, council rates), you name it! The cost of immigration is deeper than many realise.

But the full cost of immigration is not measured and it is certainly not politically correct nor convenient to report it.

Immigration harm is not perceived by government and business's short-term selfish economic benefits - jobs filled by foreigners.

TIME TO AUTO-DEPORT CONVICTED IMMIGRANTS

Auto deportation of immigrants convicted of serious crimes is long overdue. It must not matter if the person has residency status or has been granted citizenship. If they then commit a serious crime and are convicted they have breached their residency conditions.

Anyone born overseas who is convicted in Australia of a serious crime needs to be automatically deported - residency status, citizenship status - either made null and void - and ousted never to return!

As if Australia doesn't have enough criminals of its own? Who needs more?

Indeed all countries should reciprocate - deport criminal Australians back to Australia to serve their time at Australian taxpayer expense. Quid Pro Quo! All is needed is for the Australian Government to negotiate bilateral standing agreements with the relevant countries.

Had we had this Aussie-respectful policy in place, Corby and the Bali Nine would be in Australian gaols now - rightly or wrongly. But we'd have only Australians in Australian gaols!

Australia has enough of its own criminal element without inviting more!

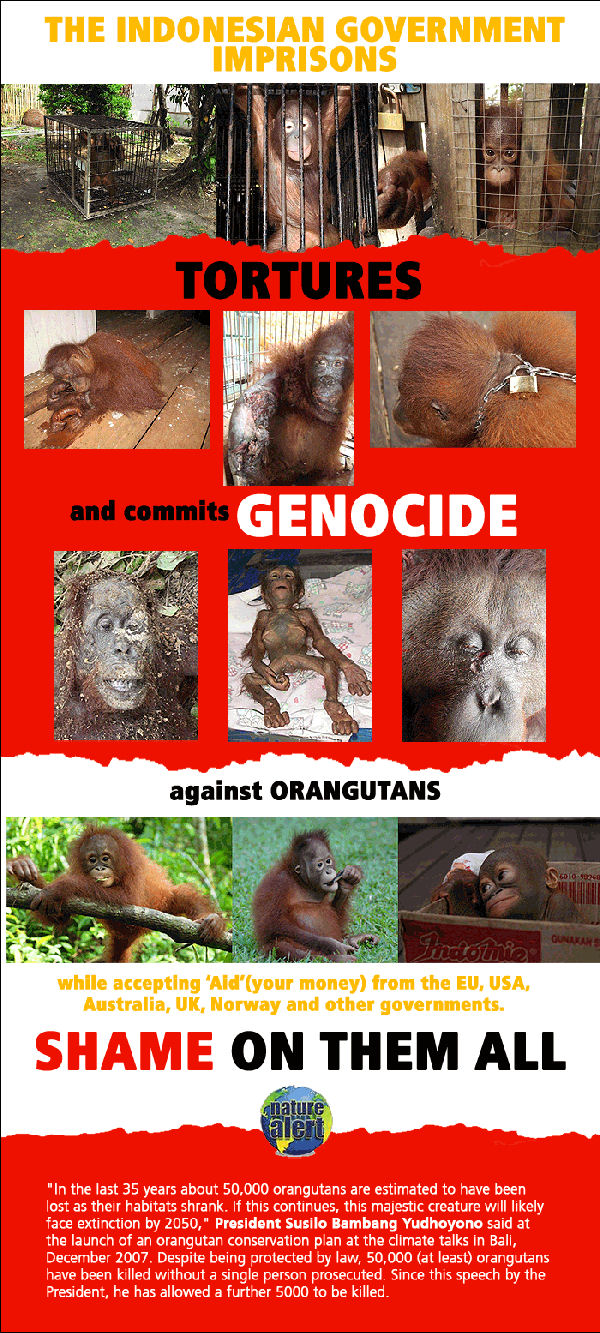

Frodo still has pellets in the stomach. Condemnation from the Queensland government is rather shallow when biodiversity in southeast Queensland is under pressure from habitat loss primarily due to increased urbanisation, driven by population growth, a fact stated in the State Government’s State of the Region (SEQ) report.

Frodo still has pellets in the stomach. Condemnation from the Queensland government is rather shallow when biodiversity in southeast Queensland is under pressure from habitat loss primarily due to increased urbanisation, driven by population growth, a fact stated in the State Government’s State of the Region (SEQ) report.

Unless there's economic growth, we're not making progress

Unless there's economic growth, we're not making progress

Whatever you think about 9 11, this story is so revealing of the contempt our public media and our Primeminister have for public opinion and free expression and for that reason needs to be promoted. (Ed.) The interview by Jon Faine of Kevin Bracken about 9/11 on 20 October 2010 was "possibly the most biased ever heard in Australia on radio broadcast by the tax payer funded Australian Broadcasting Corporation. This attack by Faine of Bracken's questioning the 9/11 events included a torrent of ad hominem slurs and an absolute refusal to discuss any evidence that the events were anything but what we have been told by our governments. Interesting to note that John Faine is now complaining that the ABC has been

Whatever you think about 9 11, this story is so revealing of the contempt our public media and our Primeminister have for public opinion and free expression and for that reason needs to be promoted. (Ed.) The interview by Jon Faine of Kevin Bracken about 9/11 on 20 October 2010 was "possibly the most biased ever heard in Australia on radio broadcast by the tax payer funded Australian Broadcasting Corporation. This attack by Faine of Bracken's questioning the 9/11 events included a torrent of ad hominem slurs and an absolute refusal to discuss any evidence that the events were anything but what we have been told by our governments. Interesting to note that John Faine is now complaining that the ABC has been

Mayor Robert Doyle has recommended that powerful owls be encouraged back to Melbourne's parks in order to reduce the possum population. He may be desperate for publicity, but he is giving a poor example. It sounds mean to possums, which he misrepresents as 'vermin' and might encourage still more cruelty to them by ignorant people. An anonymous contributor writes, "Mayor Robert Doyle is focusing on the wrong pest. ..." (This article first appeared as a comment by Nimby,

Mayor Robert Doyle has recommended that powerful owls be encouraged back to Melbourne's parks in order to reduce the possum population. He may be desperate for publicity, but he is giving a poor example. It sounds mean to possums, which he misrepresents as 'vermin' and might encourage still more cruelty to them by ignorant people. An anonymous contributor writes, "Mayor Robert Doyle is focusing on the wrong pest. ..." (This article first appeared as a comment by Nimby,

To many, xmas has become an annual social pressure. The thought of each looming xmas heralds anxiety and stress and an imposed orthodox dogma. To a great number it brings on depression.

To many, xmas has become an annual social pressure. The thought of each looming xmas heralds anxiety and stress and an imposed orthodox dogma. To a great number it brings on depression.

URGENT: Please lend your support by attending at Supreme Court to Victorian Government prosecution of Brown Mountain protesters. Tomorrow, Wednesday at 10:00am, (10 November 2010) the Department of Sustainability and Environment will proceed with its prosecution of the individuals charged with protesting at Brown Mountain. meet outside the Magistrates’ Court at 9:15am, corner of Williams and Lonsdale Street Melbourne. I will be there to meet you and direct you to the relevant Court room. This is a political cause of deepest importance. The Victorian Government and the ALP's involvement in forest crimes goes back years. The forest protesters are our bravest democratic and environmental activists. We must support them for all that they do for the rest of us.

URGENT: Please lend your support by attending at Supreme Court to Victorian Government prosecution of Brown Mountain protesters. Tomorrow, Wednesday at 10:00am, (10 November 2010) the Department of Sustainability and Environment will proceed with its prosecution of the individuals charged with protesting at Brown Mountain. meet outside the Magistrates’ Court at 9:15am, corner of Williams and Lonsdale Street Melbourne. I will be there to meet you and direct you to the relevant Court room. This is a political cause of deepest importance. The Victorian Government and the ALP's involvement in forest crimes goes back years. The forest protesters are our bravest democratic and environmental activists. We must support them for all that they do for the rest of us. Victoria needs independent candidates. Please consider standing if you opposed to the Government and the Opposition's policies on land-use planning, energy and population. Send us information and we will do our best to publicise your campaign. We value independents at candobetter.org Good luck!

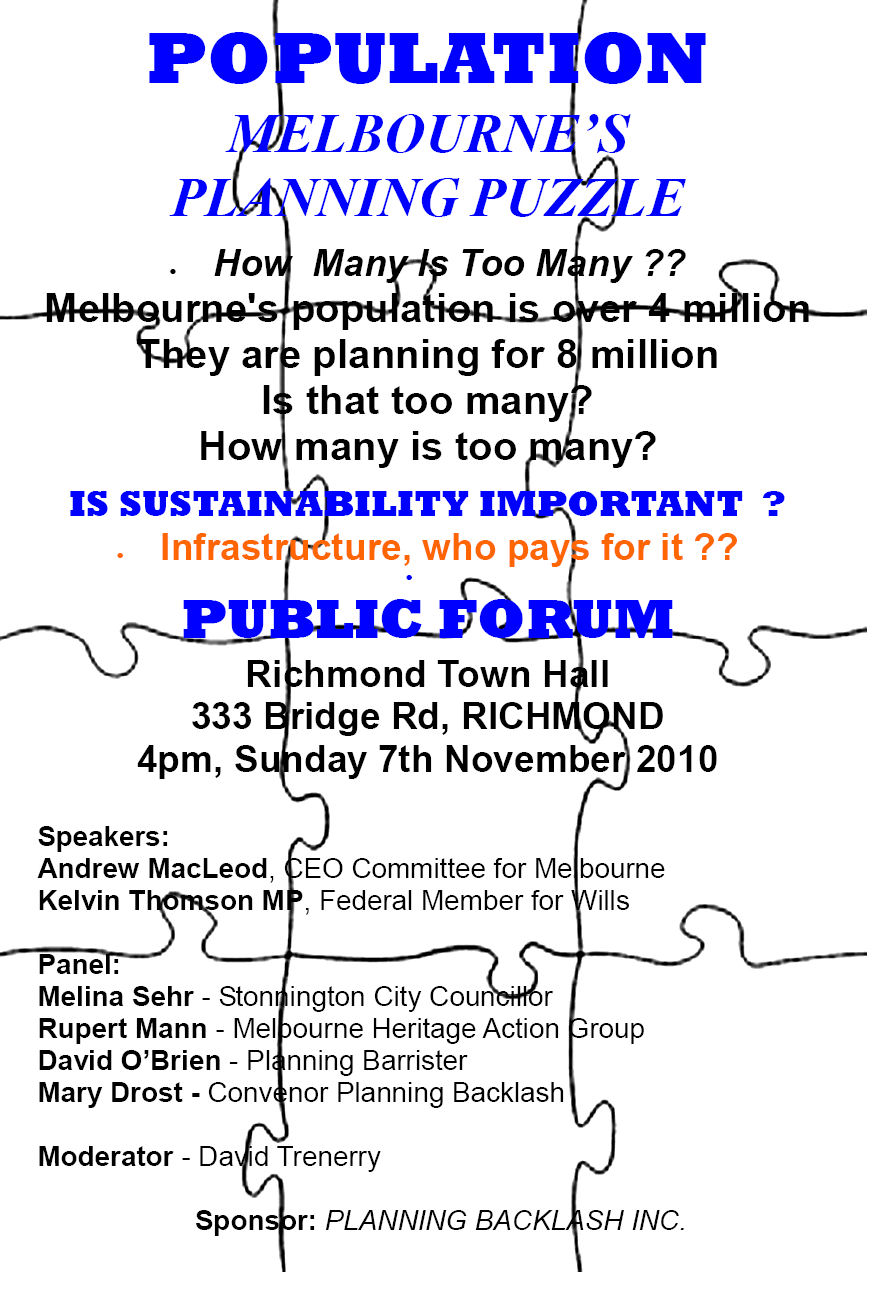

Victoria needs independent candidates. Please consider standing if you opposed to the Government and the Opposition's policies on land-use planning, energy and population. Send us information and we will do our best to publicise your campaign. We value independents at candobetter.org Good luck! Film and text of speech now available inside article. Speech given at Planning Backlash Forum of 7 Nov 2010: "In July last year I made a 22 page submission to the Victorian Government titled “5 Million is too many: Securing the Social and Environmental Future of Melbourne”. So given that I think 5 million would be too many, you can imagine what I think of the idea of doubling Melbourne’s population to 8 million. Melbourne’s population is growing on a scale not seen in Australia before, swelling by almost 150,000 people in the last two years. Melbourne’s population is growing by more than 200 people per day, 1500 per week, 75,000 per year. This is much faster than all other major Australian cities. It will give us another million people in 15 years."

Film and text of speech now available inside article. Speech given at Planning Backlash Forum of 7 Nov 2010: "In July last year I made a 22 page submission to the Victorian Government titled “5 Million is too many: Securing the Social and Environmental Future of Melbourne”. So given that I think 5 million would be too many, you can imagine what I think of the idea of doubling Melbourne’s population to 8 million. Melbourne’s population is growing on a scale not seen in Australia before, swelling by almost 150,000 people in the last two years. Melbourne’s population is growing by more than 200 people per day, 1500 per week, 75,000 per year. This is much faster than all other major Australian cities. It will give us another million people in 15 years."

There is an unrelenting media campaign to tell Canadians that we must grow our population. We need more babies and more immigrants or very bad things will happen. But there are voices that question this assumption. They are heard on the streets, in the pubs and at the dining room table. But they are seldom heard in the media. Especially not on the airways of the CBC, that vehicle of growthist PC propaganda which all taxpayers are forced to endow.

There is an unrelenting media campaign to tell Canadians that we must grow our population. We need more babies and more immigrants or very bad things will happen. But there are voices that question this assumption. They are heard on the streets, in the pubs and at the dining room table. But they are seldom heard in the media. Especially not on the airways of the CBC, that vehicle of growthist PC propaganda which all taxpayers are forced to endow.

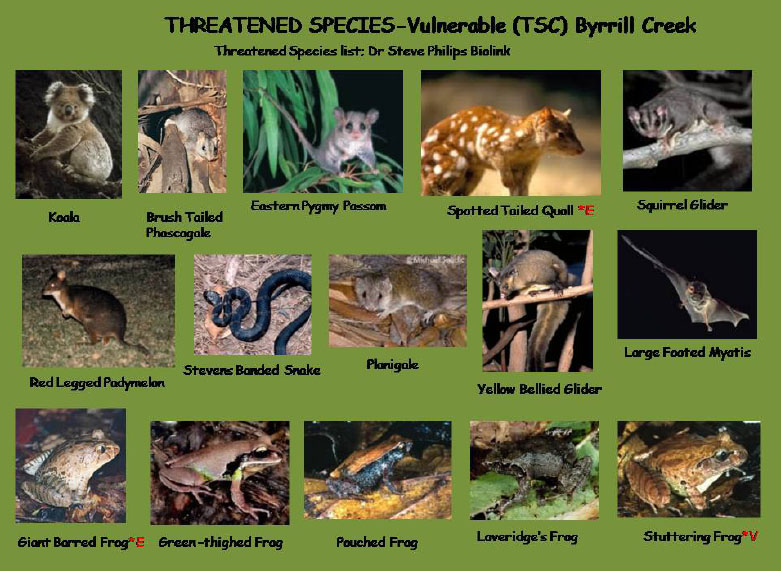

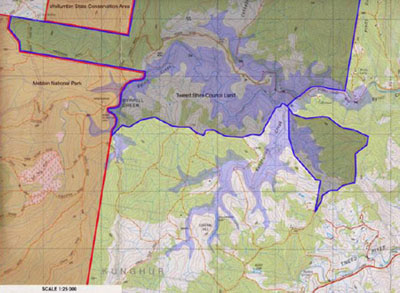

Controversial Tweed Shire Council has a history of making poor environmental decisions that are hugely unpopular with the largely Green-oriented residents. It is the second most complained about council in New South Wales. However in November 2010 the councillors voted for the worst possible blunder which will be recorded as a major crime against Nature.

Controversial Tweed Shire Council has a history of making poor environmental decisions that are hugely unpopular with the largely Green-oriented residents. It is the second most complained about council in New South Wales. However in November 2010 the councillors voted for the worst possible blunder which will be recorded as a major crime against Nature.

(Cr Skinner, Cr Polglase and Cr Youngblutt)On November 1st, Mayor Kevin ‘Green’ Skinner (who declared on his election his commitment to 'preserving this lovely pristine environment'(see http://www.tweednews.com.au/story/2010/09/21/skinner-tweeds-new-mayor/ ) used his casting vote to push the motion for a dam through, contrary to convention to vote with staff recommendations. The ‘Three Stooges’ pro-development councillors who voted for the dam, also dogged a motion for an independent review of water demand management for the shire.

(Cr Skinner, Cr Polglase and Cr Youngblutt)On November 1st, Mayor Kevin ‘Green’ Skinner (who declared on his election his commitment to 'preserving this lovely pristine environment'(see http://www.tweednews.com.au/story/2010/09/21/skinner-tweeds-new-mayor/ ) used his casting vote to push the motion for a dam through, contrary to convention to vote with staff recommendations. The ‘Three Stooges’ pro-development councillors who voted for the dam, also dogged a motion for an independent review of water demand management for the shire.

Mt Warning is a sacred site to the local aboriginal population and contains numerous cultural heritage sites within the Byrrill Creek area. There was a 3-day indigenous study showing 26 registered sites confined to the original aboriginal inhabitants (camp sites etc). In 2009 4 new sites were found. A dam would cut highly significant pathways. These sites are significant and important to the indigenous people living here.

Mt Warning is a sacred site to the local aboriginal population and contains numerous cultural heritage sites within the Byrrill Creek area. There was a 3-day indigenous study showing 26 registered sites confined to the original aboriginal inhabitants (camp sites etc). In 2009 4 new sites were found. A dam would cut highly significant pathways. These sites are significant and important to the indigenous people living here.

* Of countries containing large endowments of biodiversity, Australia is unique in another very significant way. Of all the countries classified as megadiverse, Australia is one of only two countries in the high income category. This position carries a special responsibility and implies that a high standard of biodiversity protection can be expected in Australia. It also carries with it an opportunity too for world leadership”. (Aust Govt website: State of Environment report 2001)

* Of countries containing large endowments of biodiversity, Australia is unique in another very significant way. Of all the countries classified as megadiverse, Australia is one of only two countries in the high income category. This position carries a special responsibility and implies that a high standard of biodiversity protection can be expected in Australia. It also carries with it an opportunity too for world leadership”. (Aust Govt website: State of Environment report 2001)

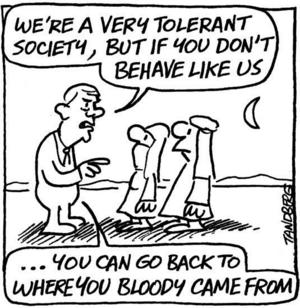

Australians have found it very hard to protest against high immigration because of constant subtle messages from government and media implying that they had no right to object. They have been given the idea that there was nothing special about them that gave them the right to object. They only lived here. Although only Australians might vote in governments, the importance of this was subsumed to a cult of plutocracy, where governments prioritised commercial and corporate demands over the wishes of the actual electorate. The mainstream press (the ABC, the Murdoch Press, the Fairfax Press) promoted a cult of elite authoritarianism and the official alternative press never really encouraged questioning of this process on issues of real dissent. And the elite authorities all endorsed 'multiculturalism'. One has only to glance at the

Australians have found it very hard to protest against high immigration because of constant subtle messages from government and media implying that they had no right to object. They have been given the idea that there was nothing special about them that gave them the right to object. They only lived here. Although only Australians might vote in governments, the importance of this was subsumed to a cult of plutocracy, where governments prioritised commercial and corporate demands over the wishes of the actual electorate. The mainstream press (the ABC, the Murdoch Press, the Fairfax Press) promoted a cult of elite authoritarianism and the official alternative press never really encouraged questioning of this process on issues of real dissent. And the elite authorities all endorsed 'multiculturalism'. One has only to glance at the

Recent comments