The Queensland Government's Draft South East Queensland Regional Plan, far from achieving its lofty claimed goals of "protect(ing) and enhanc(ing) the quality of life", landscape values, biodiversity and natural assets of the region, will, instead, turn even much of that region into an economically depressed, crowded and ecologically unsustainable slum for no better purpose than to keep profits flowing into the pockets of developers who largely bankroll the ruling Queensland Labor Party.

An earlier unfinished draft of submission was mistakenly published on 17 Mar 09.

Dr. Jane N. O'Sullivan

Chelmer Qld

Draft SEQ Regional Plan Submission

Department of Infrastructure and Planning

Reply Paid 15009

City East Qld 4002

General comments

The current draft SEQ Regional Plan 2009-2031 (the Plan) is a travesty against the people of South East Queensland. It should be withdrawn, and a new process undertaken which addresses its shortcomings.

- It does not achieve its own stated goals. It does not "protect and enhance the quality of life", landscape values, biodiversity and natural assets of the region, but accelerates the development processes which have demonstrably undermined them to date. It fails to acknowledge fundamental conflicts between stated goals (such as biodiversity preservation and population growth) nor does it provide any process or guidelines for resolving such conflicts.

- It fails to achieve key elements of a regional plan, required under the Integrated Planning Act S.2.5A.11, to identify key regional environmental, economic and cultural resources to be preserved, maintained or developed, and define how that is to be achieved.

- It conflicts with the National Strategy for Ecologically Sustainable Development. The goal, core objectives and guiding principles of this strategy should be integral to the Plan. Instead, its regulatory provisions directly undermine existing controls that defend these principles.

- It ignores the findings of the State of the Region Report for SEQ (2008), which showed biodiversity loss and climate change impacts as grave problems in the region. It makes only token attempts to reduce the intensity of pressures known to be exacerbating these vulnerabilities, while significantly increasing their scale. The outcome will certainly be increased biodiversity loss, greater greenhouse gas emissions and greater vulnerability to climate change impacts.

- It pre-empts the findings of a number of studies and policies currently underway, thus failing to integrate their conclusions, and limiting capacity to incorporate changes that may be recommended by these processes. These include SEQ Natural Resource Management, Water Strategy, Rural Futures Strategy, Biodiversity Value Assessments, Climate Change Response, Peak Oil Response, and the SEQ Infrastructure Plan and Programs.

- It undermines a core component of quality of life, namely the self-determination of communities through open and equitable democratic processes.

- The Plan limits and overrides capacity of local councils to control development.

- It compromises the Desired Environmental Outcomes of local government planning schemes.

- It increases discretionary power of the Minister for Planning to gazette areas for any level of development without opportunity for community consultation or appeal.

- It increases the scope of landholder rights of use without referral or environmental impact assessment, on land outside the urban footprint.

- Importantly, it fails to provide complete and balanced data on both the resource base and the impacts of the proposed development, to enable informed public response.

All these travesties are done in the name of one single goal, that of incorporating an additional 1.6 Million people into SE Queensland.

If that growth were inevitable, the best that could be said of the Plan is that it is an attempt at damage mitigation, dressed up (deceitfully) as progress.

However, neither the inevitability nor the costs and benefits of this population growth have been explored.

In the first instance, it is important to acknowledge the extent to which the Plan itself acts to attract more population. Land releases, removal of regulatory barriers, and the commitment of State Government to fund the infrastructure requirements of new residents (through the Metropolitan Development Program), all fuel the rate of growth. It is argued that these things are needed to improve housing affordability, but in fact they do the opposite by fueling property speculation. [DRO 8, Policy 8.4.1: the Queensland Housing Affordability Strategy is misguided and entrenches outdated patterns of urban sprawl and socioeconomic stratification.]

Secondly, it must be noted that there are no new sources of funding identified in the Plan. The ideals of good urban planning and infrastructure espoused in the Plan are not new, but to date funding has not been adequate to achieve these goals. There is no basis to expect that an increased rate of demand growth will make the provision of good services any easier than it has been in the past.

Part B: regional vision and strategic directions

"The regional vision for SEQ is a future that is sustainable, affordable, prosperous, liveable and resilient to climate change."

If the Plan, as currently drafted, were to take effect, NOT ONE of those criteria would be greater in 2031 than today.

The document avoids saying SEQ will be safer, healthier, more accessible, more inclusive, more affordable, more livable or more resilient to climate change. The authors know that these objectives cannot be delivered. This entire section is an exercise in weasel words.

It is noted that no comparative adjectives are used in the vision statement. Communities may indeed be described as safe, healthy, accessible and inclusive, depending on what you are comparing them with. The document avoids saying SEQ will be safer, healthier, more accessible, more inclusive, more affordable, more livable or more resilient to climate change. The authors know that these objectives cannot be delivered. This entire section is an exercise in weasel words.

The strategic directions do claim that the plan intends to create a more sustainable future. However, there is no doubt that the 2031 SEQ envisaged will consume more energy and water than the current SEQ. Only aspirational reference is made of improved building standards to reduce energy requirements and withstand extreme weather events [DRO 1: Policy 1.3.5 and Program 1.4.5], but no evidence is given that these gains will off-set the increase in dwelling number. Little attempt is made to restrict development on low-lying coastal plains or forest fringe areas at increasing risk of bushfire, indeed several such areas are inappropriately included in the urban footprint.

Perverted Economic Priorities

Anna Bligh has said that population growth is needed to maintain jobs in the building sector1. This irrational statement is on a par with Maurice Iemma's claim (in relation to climate change response) that there is no point saving the environment if doing it harms the economy. Both show an alarming lack of understanding of the extent to which our quality of life depends on our natural resource base.

If the Premier wants to preserve these jobs, we could employ people to dig holes and fill them in again. This would have equal benefit to existing Queenslanders (none but the salaries involved), and far less adverse impact. It would be cheaper than the publicly funded infrastructure needed to service the extra dwellings. But if completely futile activity is an improvement on current proposals, it's easy to see that we could achieve a far better outcome employing the same people to implement the changes we need to transform into a low-carbon economy. We need green jobs, replacing unsustainable activities, not brown jobs adding to them.

In other words, the proposed population trajectory is part of a model of economic development for the region, which is inherently unsustainable. It places construction as a priority focus, to the detriment of tourism (through crowding and degradation of our natural attractions), manufacturing (through uneconomic land values and increased costs of services), and the cost of living and quality of life (reversing the stated intention of economic growth). I do not need to justify the statement that population growth is unsustainable. All sensible people agree that there must be a limit to the number of people we can accommodate in the region, and that quality of life will erode as we approach that limit. That the limit is near if not surpassed, and that quality of life is already eroding through overdevelopment, is apparent to all. There can be no doubt that climate change will further reduce the region's carrying capacity. Therefore, to increase our economic dependence on the growth process, knowing that it must soon end, is foolhardy. It is the antithesis of "sustainable economic development".

What is it that the planners are aiming to create? What is the vision for SEQ's future? The only constant offered seems to be the rate of change. The Plan gives an idea of what the region might look like with 4 million people, but what about 6 million? Or 10 million? Such numbers are only a few decades away at current growth rates. What will be our legacy in 200 years? [DRO 1 and DRO 2 are oxymoronic and incompatible with the scale and style of growth proposed. These objectives can only be conceived with a steady-state future in mind, but the Plan offers no route towards population stability.]

However, limits to growth seem to be far from the minds of both politicians and media. We are frequently invited to celebrate that Queensland's growth has surpassed Victoria's, or that we will soon be Australia's second biggest State. I cannot help being reminded of Yertle the Turtle.

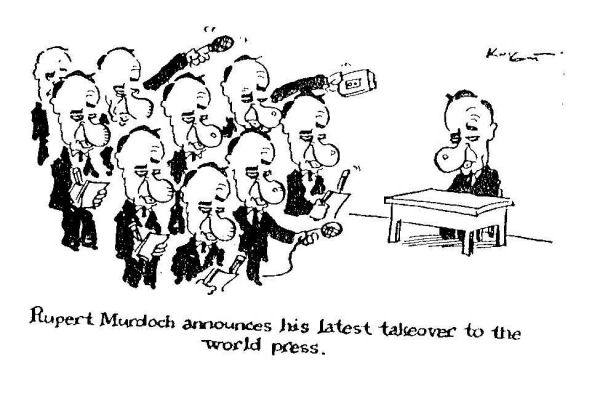

It is not difficult to see how the Premier has come to this perspective. The property industry has the ear of government, because they fund both main political parties. It is up to informed citizens to protest at this corruption of public interest in the name of short-sighted private interests. I make this submission in the spirit of such protest, but also to propose that there are achievable alternatives, both in process and outcome.

The Costs of Growth

Both State and Federal Governments champion the importance of population growth for our economic progress. However, they fail to relate the resulting growth in GDP to per capita wealth.

The Productivity Commission's 2006 research report, Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth2 modeled a 50% increase in skilled immigration, and found that, while GDP increased 4.6% over 21 years (a small proportion of the expected GDP growth), per capita income increased only 0.71% (about 0.03% per annum). Most of the gain accrued to the skilled migrants themselves and to capital owners, and the effect on incomes of existing residents was negative. The report further commented that a range of impacts on living standards and environment are also likely, but these were not economically quantifiable. It left open to the reader to interpret whether the net effect on wealth and wellbeing was positive or negative.

A further omission from this GDP-based analysis is the fact that a considerable proportion of the economic activity in a growing population does not enrich the current population, but is undertaken on behalf of future population at a cost to the current population. For a stable population, the same quality of life could be delivered for a lower per capita GDP.

Increased costs are most easily quantified in the areas of skills and infrastructure.

Skills shortages have been used as a primary argument for the need for high immigration levels. However, immigration is more likely to have exacerbated than relieved skills shortages. Consider that in a stable population, post-secondary training in trades and professions is needed to replace retiring skilled workers. Assuming an average working life in the order of 33 years for each skilled worker, the annual graduation needs to be around 3% of the total workforce in each skill area. In a growing population, graduations also have to grow the total workforce (not the population of graduates) proportionally. For Australia's current growth rate of 1.8% per annum, graduate requirements increase from 3% to 4.8% of the workforce: a 60% higher training burden than in a stable population. Over the past decade, as Australian population growth has increased, spending on higher education has not increased to accommodate this extra burden. It is little wonder that skills shortages have intensified. Immigration may have alleviated shortages in selected areas, but has increased them across the board. Stabilizing population would make a far more cost-effective contribution to aligning training capacity with training needs.

Given that growth requires us to replace still-functional infrastructure with higher capacity versions, the cost may be even higher.

The working life of individual items of infrastructure may vary over a wider range than that of people, but a similar average of about 33 years is plausible, if conservative. The longer the actual lifespan, the greater the extra burden from growth. Therefore, a similar or greater increase in the total infrastructure burden exists, as a result of our rate of population growth. Given that growth requires us to replace still-functional infrastructure with higher capacity versions, the cost may be even higher.

In Queensland, the growth rate is much higher than the national average. At 2.5% annual growth, the increase in infrastructure and training burden is likely to be in the order of 85% higher than a stable population.

If public expenditure does not increase to cover the burden of our increased growth rate, then the capacity of public facilities and services cannot keep pace with the increased demands on them. We do not stand still -- we rapidly go backwards, eroding quality of life particularly for the most vulnerable, who rely most on public services. This is exactly what we have witnessed in Queensland, in health, education, transport, water, and other services. It is a direct consequence of our growth. Yet growth is pursued as the solution.

It is very difficult to estimate the exact cost of infrastructure for each additional person. Government does not collate and publish appropriate data. A colleague of mine attempted to make such an estimate, and arrived at a figure in the order of $200,000. This is not implausible: a cost of $2 Billion to provide all the facilities for 10,000 people, including schools and universities, hospitals and health clinics, roads, sewage, water supply, electricity generation, storm water management, recreational facilities, offices and equipment for public servants and publicly funded NGOs, port and rail infrastructure, waste transfer stations, public transport rolling stock etc. If the Government wants to dispute this figure, I welcome it to do the accounting and publish the actual cost.

Imagine if the State were to levy each additional dwelling with a fee of $427,000, to cover the increased infrastructure for 2.14 people (the average household size anticipated in the Plan). Would people still be flocking to our region?

Our tax base is overstretched. But the Government contrives to hide this cost from us all.

However, by not doing this, the Government is levying each of its existing tax payers to subsidize the newcomers. That this levy is unaffordable is demonstrated by the crises in our hospitals, schools, water and transport systems. Our tax base is overstretched. But the Government contrives to hide this cost from us all.

The Plan has acknowledged the particular challenge of broadhectare infrastructure provision [DRO 10], and states that "contributions may be achieved through other mechanisms such as third party financing". This is extremely worrying. Privatization of public infrastructure, especially when this provides a monopoly, has failed to deliver public benefit wherever it has been used. It should be explicitly ruled out as part of the Plan. Instead, the affordability of infrastructure should feed back to regulate the rate of growth we can afford.

It may be argued that the State Government does not control our national immigration policy, and the consequent inflow of people to SEQ. Yet no attempt has been made by the State to challenge it.

If the State Government were to point out to the Federal Government that each additional Queenslander costs it $200,000, and suggest that extra tax revenue is essential to cover this, it is unlikely that the current immigration policy would be sustained.

It may be argued that the State Government does not control our national immigration policy, and the consequent inflow of people to SEQ. Yet no attempt has been made by the State to challenge it. Instead, the Queensland Government has acted to suppress the choice of local councils to cap their populations. If the State Government were to point out to the Federal Government that each additional Queenslander costs it $200,000, and suggest that extra tax revenue is essential to cover this, it is unlikely that the current immigration policy would be sustained.

Part D8: smart growth

Urban Footprint and Urban Infill

The Plan purports to "manage" growth, through defined additions to the urban footprint, and a focus on "smart" infill development to achieve compact urban development, in theory reducing car dependence by concentrating growth close to public transport nodes and employment opportunities.

In practice, these claims fall short of the spin.

The attraction of broadhectare development over infill is that it is cheaper for developers. However, this is because the State (i.e. the existing tax payers) subsidizes the development with the provision of public infrastructure and services. For the State, infill development is cheaper up to a point, as it is cheaper to increase the capacity of existing services than to duplicate them in new locations. This cost of broadhectare development is acknowledged in the Plan, and mechanisms for planning the infrastructure are discussed. However, it is not apparent how better planning will actually deliver better infrastructure, when we are unable to fund our current infrastructure needs.

The main area for broadhectare development, the western corridor, has little to recommend it for either residence or business. If it was a desirable location, it would have developed already. It is chosen only as the area least likely to arouse significant protest. Its existing residents enjoy spacious semirural settings, to off-set their not-yet-too-onerous commuting costs. These values will be lost by the proposed density of development. Forcing new growth into this area will create a new slum. Mostly, those with the least options will choose to live there. Goodness knows what level of public funding will be needed to build desirable public facilities and subsidize the establishment of local businesses, in a probably futile attempt to prevent the area turning into a low-socioeconomic enclave. This has not been costed as part of the Plan. [DRO 8: Policy 8.4.1: note that the Queensland Housing Affordability Strategy specifically directs low-cost housing to new broadhectare developments where they have least access to services.]

Would Sydney, with the benefit of hindsight, choose to add a Western Sydney, with all its socioeconomic problems, if it could possibly be avoided?

Would Sydney, with the benefit of hindsight, choose to add a Western Sydney, with all its socioeconomic problems, if it could possibly be avoided? Brisbane is now at that point in history, about to launch into a massive project to create our own Western socioeconomic millstone.

The claim that the new areas will "accommodate appropriate employment capacities" ignores the drivers of population growth into the region [Policy 8.2.4]. People come for employment opportunities in existing areas. They look for housing in outer suburbs because of its affordability, availability or utility compared with housing closer to their employment. The jobs that are likely to be created in the neighbourhood are only a fraction of the suburb's economy: the people needed to service the new population. They illustrate the multiplier effect of population growth, and this effect is greater in more disbursed outer suburbs than in higher density areas, as the latter have greater economies of scale for service provision.

It is unclear how the Plan proposes to influence the proportion of infill to broadhectare. One must assume that the projection of 44% infill is only an extrapolation of current rates of subdivision. It is implied that this is an optimal rate, to achieve "smart development". However, if infill is acknowledged to provide lower environmental impacts, the best way to encourage it is to limit the release of broadhectare land. This is not proposed. On the contrary, the rate of land release is to be accelerated.

As for urban infill, the impression is given that most development will be high-density housing around transport and employment nodes [Policy 8.1.1]. But the Plan contains no effective measures to ensure this happens. It may only serve to encourage local councils to lift density limits around those nodes. A recently published study from Monash University3 demonstrated that similar intentions in the Melbourne 2030 plan have not been realized in the City of Monash. Instead they observed that "redevelopment proposals are more opportunistic than systemic" and "activity centres are not the magnet for high density development as originally envisaged by the Melbourne 2030 policy". They conclude:

"The City of Monash infill pattern resulting is one mapped as a dispersed pattern of dual occupancy and unit development. The resulting redevelopment is thus unlikely to deliver many benefits of the type most sought under the Melbourne 2030 planning scheme. Rather, the existing pattern of transport within established suburbia, which involves a heavy reliance on the private car, will be adopted by those living in the new infill developments."

Public transport proximity commands a premium in the real estate market, so if development at the nodes is left to developers, it will target the high end of the market, in direct competition with detached housing, rather than providing small units at affordable prices.

The only way the Government could implement the sort of "smart development" outlined in the Plan, would be by compulsorily acquiring extensive areas of land at the transport nodes, and commissioning their redevelopment. Not such an unattractive proposition, when compared with the cost of servicing new broadhectare developments. Perhaps politicians fear local protest -- from voters less expendable than those in the Mary Valley. Yet, if done well, the outcome is likely to be far better than the continuation of pragmatic infill, with its accompanying loss of green space, increased local traffic and heat island effect. It may be an effective way to achieve affordable housing with adequate mobility for the elderly to sustain independent living. Public transport proximity commands a premium in the real estate market, so if development at the nodes is left to developers, it will target the high end of the market, in direct competition with detached housing, rather than providing small units at affordable prices.

If high density development could only be built on State-acquired land, it would take a lot of heat out of the property market, and improve housing affordability far more than the release of broadhectare land.

Of course, it would be immensely unpopular with developers and land speculators, who receive an enormous windfall benefit when height or density restrictions are lifted. If high density development could only be built on State-acquired land, it would take a lot of heat out of the property market, and improve housing affordability far more than the release of broadhectare land.

There has been some recent media debate, particularly in Melbourne, about proposals to build "up instead of out".4 Note that this is not what I am suggesting, although there are elements in common. The aim of redeveloped precincts would be to limit the impact of urban infill on the surrounding leafy suburban streets by providing for unavoidable growth in an orderly way, as well as providing less car-dependent housing options and ensuring affordable housing is near transport and services. This strategy will only provide a sustainable solution in the context of transitioning to a stable population. It is not intended as the first stage of a cancerous growth that would spread across the urban landscape, but a way of giving a viable focal point to neighbourhoods and achieving a housing mix better suited to our future demographic profile. Building height should be limited to a walkable 5 levels, and open spaces should be traffic free. The style would be more like old European town centres, rather than the towering and alienating unit developments hemmed in by busy roads, that are beginning to surround Brisbane city [see photographs on p 5 and 13 of Part E].

Policies 8.7.1 and 8.7.3 favour street-frontage retail development rather than enclosed malls. This is regressive and results in traffic-dominated public spaces. Internationally, the most successful centres combine open malls (traffic-free streets) with enclosed malls containing or adjoining rail stations.

[DRO 12] There also needs to be a far greater integration of programs. If car dependence is to be reduced, new high density housing units should be encouraged not to accommodate cars. A limited number of car park spaces might be available for hire . However, for people to choose not only to commute without a car, but to not own a car, is a difficult choice in our current system. Numerous international examples offer alternatives to remedy this difficulty. In Switzerland, the railways run a car pool system, where subscribers can pick up a car at most railway stations, and use it for a nominated time. The fee is modest, and compares favorably with owning a car for infrequent use. Clients can secure their booking by mobile phone, and this locks the car to any but their personal access card. I have recently learned that such car pool systems have been established in Sydney and Melbourne, but have been impeded in Brisbane due to refusal of the Council to provide dedicated parking space for the pool cars. Bus routes need to offer far more local neighbourhood access, and routes between the main radial corridors rather than forcing clients to go via the city. Also in Switzerland, in neighbourhoods where it is not economic to run frequent regular bus routes, buses can be booked with 20 minutes notice, to take clients door-to-door, via other pick-ups as needed. The fee is a standard bus fee, much more attractive than a taxi but still cheaper for the municipality than running low-occupancy routes. Thus bus drivers and their clients are free to negotiate their own schedule and routes.

The Queensland petrol rebate constitutes a perverse incentive, acting against emissions reductions. In place of the rebate, the State should provide a no-fault road trauma compensation scheme and end compulsory third-party insurance by indemnifying licensed drivers from third-party claims. The current scheme, in which every vehicle owner is required to have a separate insurance policy individually negotiated with an insurer but providing identical cover, is entirely unnecessary, a honey-pot for insurance providers, and a significant further stress for road trauma victims facing the complications and expense of making claims. Insurance is a means of risk-spreading, but the aggregate risk to the State is relatively predictable and does not need spreading. Importantly, the State would receive the benefit of increasing road safety and reducing road use. The value to the average driver, and the cost to the State, would be similar to the petrol rebate, but those who drive less would be rewarded. [This would be a State-wide initiative, but is relevant to the demand-management goals of the Regional Plan -- D10.3]

Bicycles have even lower environmental impact than public transport, and have added advantages of freedom from routes and schedules, and promoting healthy exercise. However, personal safety of cyclists on our congested roads forms a major deterrent for many people from taking up cycling. If this is to be remedied, much more serious efforts need to be made to balance cycle and car priorities on our roads. The on-road cycle lanes currently used do not provide sufficient connectivity for commuter routes, and do not significantly improve safety for cyclists. They tend to encourage cyclists to ride too close to parked cars, putting them at greater risk of car door incidents. All parking should be removed from on-road cycle lanes. Off-road bikeways need to be designed for commuters, who wish to travel at efficient speeds, rather than the winding and out-of-the-way recreational routes that currently dominate Brisbane's off-road cycle paths. Queensland driving licence tests should incorporate questions relating to cyclists' rights to share roads, and expected etiquette and safety measures for cars to respond to cyclists. [Currently the Plan has no substantive policies to support bicycle use. Policy 12.2.2 does not address the existing barriers to cycling as a means of transport.]

Despite the Plan's intention to promote sustainable travel options [Policy 12.2.2 and 12.2.3], it is difficult to see how these options can flourish in a landscape increasingly congested with cars. Increasing population density through either pragmatic infill or broadhectare sprawl will increase traffic volumes, with a positive feedback effect that roads become less friendly to active transport, and people choose cars instead. A partial solution is to restrict car access to activity centres, offering park-and-ride options instead. But without limiting population growth, reclaiming the streets from the car will be an uphill battle.

Clearly the Plan is not written with the intention of achieving best outcomes for SE Queensland's people. It is a plan written to deliver maximum benefit to developers.

There are many fine sentiments expressed in the Plan, but they lack a realistic means of achievement, and avoid quantitative goals or benchmarks. Clearly the Plan is not written with the intention of achieving best outcomes for SE Queensland's people. It is a plan written to deliver maximum benefit to developers.

Recommendations

I have no illusions that the following suggestions will be embraced by State Government. However, I wish to make the point that there are realistic, affordable alternatives to the pragmatic, developer-driven growth rush that we currently endure.

- [Part B] Acknowledge openly that additional population threatens the biodiversity and quality of life in South East Queensland. Emphasize that the plan's aim is to minimize the negative impacts of growth, and to ensure that the process of accommodating growth does not attract growth. Outline the steps the State Government intends to take to reduce immigration to the region, and explain the benefit that such reduction will yield by freeing up revenue to enhance quality of existing services and facilities.

- [Part C] Provide an accurate inventory of natural resources, including natural vegetation on both public and private land, and truthful incidence mapping of endangered species (unlike the convenient omissions of known koala habitat from the koala distribution in the current Plan). Map areas of impact from various possible (explicitly and quantitatively defined) scenarios of sea level rise, increased coastal storm intensity and increased bushfire risk, and define and justify the boundary of acceptable development to limit future climate change vulnerability. Remove areas of climate change vulnerability and remaining natural vegetation from the urban footprint, removing any current development entitlement on them. Recognize the exceptional ecological and productive value of the red soils of Redlands and the Sunshine Coast Hinterland, and prevent further urban development on them.

- [Part D8] Prohibit further subdivision of private land. Redevelopment of double-title blocks, and intensification on blocks within designated zones, would continue.

- [Part D8] Increase the mandatory environmental standards for new buildings to at least a 5 star rating, mandate minimum proportions of roof to be oriented for solar and water collection (I suggest at least 50% of roof area for solar, more for water), and limit new high-density development to a walkable 5 levels to remove residential dependence on lifts and to ensure open spaces between buildings enjoy sunshine and vegetation.

- [Part F] Reinforce local council powers to prohibit development on land of environmental significance, and to dictate the standard of impact assessment required on development applications. Do not allow developers to bypass council requirements by claiming they are stalling tactics.

- [Part D12] Do not support further road capacity expansion projects. Road development should focus on improving safety and efficiency, and better accommodating buses and small, low speed vehicles (including bicycles, but possibly accommodating next-generation light electric vehicles). Congestion should be allowed to motivate people to opt out of private car use. Rather than increasing capacity, it could be controlled via a congestion tax which increases this motivation (if carefully designed to avoid inequitable impacts, and only after provision of realistic public transport alternatives).

- [Part D12] Extend the metropolitan rail network to Gold Coast and Sunshine Coast activity centres. Extend the Ferny Grove5 and Cleveland lines to Samford and Redlands respectively, and create a spur from Oxley to the south-west suburbs. Provide regular passenger services Open the Exhibition line for regular use, with a station providing access to the Royal Brisbane Hospital precinct (in terms of car-kilometers saved per dollar spent, this would rate very highly).

- [Part D12] Provide for innovative transport options such as car pooling, on-call buses, and school buses that provide a realistic option for parents by accepting responsible custody of children and designing routes annually based on addresses of enrolled children, to pick up children within a block from their home.

- [Part D8] Acquire substantial areas of land precincts around selected suburban public transport nodes, for the purpose of redeveloping activity centres and meeting housing demand in an orderly way that avoids property speculation and population pull-factors. Apart from limited intensification on existing titles, aim for all new housing to be in walking distance of an activity centre and transport node. Precincts could be up to 400m radius, but could be staged to transition existing services and businesses to new accommodation, and may incorporate heritage features to be preserved. Tender for precinct redevelopment under best-practice standards of environmental impact, energy efficiency and social equity. Developments should combine residential, commercial and recreational functions, with traffic-free open spaces. They should not aim to provide expansive prestige accommodation, in competition with detached housing, but cater specifically for singles and couples, leaving surrounding detached housing for the larger households it serves best. Housing for people with restricted mobility should be prioritized. The sale price of units need not pay for the entire development, as it would include components that would have otherwise been publicly funded in the form of infrastructure to broadhectare subdivisions and suburban centre renewal projects. So it should be possible to provide relatively affordable housing and viable commercial rents. Such projects would attract prestigious international design bids, and would put Brisbane on the map in terms of sustainable urban design.

My proposal may be seen as authoritarian, even socialist, among free-market thinkers. I do not mean to argue against the role of private capital in a stable, well-balanced society, in which the sum of private interests approximates to public interest. However, when faced with the need for a substantial transition, requiring remodeling of many of our societal systems to accommodate peak oil and climate change, severe conflicts arise between vested private interests and long-term public interest. In such a situation, government needs to take a greater role, in controlling resources and shaping development in the public interest. This is a strategy for transition, not a socialist manifesto.

Thank you for the opportunity to comment on the Plan. I sincerely hope that its next iteration is substantially improved, as a result of this consultation process.

Jane O'Sullivan

Footnotes

1. ↑ www.theage.com.au/news/NATIONAL/Qld-govt-rejects-population-cap/2007/04/22/1177180460654.html.

2. ↑ Productivity Commission 2006. Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth www.pc.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/9438/migrationandpopulation.pdf.

3. ↑ Phan T, Peterson J and Chandra S, 2008. Urban Infill: extent and implications in the City of Monash. People and Place 16(4), 23-31.

4. ↑ The proposal from Jason Black, president of the Planning Institute of Australia's Victorian division, has probably been sensationalized in its media coverage, such as Peter Familari's article "Planning expert says Melbourne must destroy leafy eastern suburbs" in the Herald Sun, 29 April 2009.

5. ↑ This is a good suggestion, but for this to happen, built-up residential blocks that occupy land immediately adjacent to Ferney Grove Station over which the extension railway line would have to be built would have to be bought and the houses demolished. How such an astonishingly irresponsible decision as to allow such land to be built upon was arrived at would be very interesting to learn.

uses his existing powers and declares it clearly unacceptable under the provisions of the EPBC act (Section 74 B)

uses his existing powers and declares it clearly unacceptable under the provisions of the EPBC act (Section 74 B)

Recent comments