We are letting our resources luck turn to dust

Paul Cleary’s book Too Much Luck: The Mining Boom and Australia’s Future, is a timely appraisal of the dramatic economic and social impacts, as well as the political ramifications of the current resource boom.

(The reviewed work covers much of the same ground as Dirty Money of 2011 by Matthew Benns, which I am currently reading and can also recommend.) This review of Paul Cleary's book by Professor Kerry Carrington, Head of School of Justice at Queensland University of Technology was originally published on theconversation.edu.au on 25 November. It is being reprinted here with her kind permission. Professor Carrington asked that this review be republished as widely as possible.

Paul Cleary’s book Too Much Luck: The Mining Boom and Australia’s Future, is a timely appraisal of the dramatic economic and social impacts, as well as the political ramifications of the current resource boom.

Cleary argues that the resource investment stampede is squandering Australia’s precious non-renewable fossil fuels, leading to a high dollar, inflation and interest rates, at the expense of manufacturing, education and tourism industries.

There is, he argues, a strong case for a more measured approach to harvesting these resources in the long-term interests of all Australians through better taxation, saving and regulation of the resource sector. This book is not anti-mining and does not argue that resources should be left in the ground, as Stephen Kirchner would have us believe.

Cleary coins the phrase “investment stampede” to capture the seismic shifts at work. The sector is growing fast – too fast – at 15% per annum, with a pipeline investment of $174 billion. Global demand especially from Asia has fuelled this boom. Current economic returns for the mining corporations and their shareholders are staggering.

Cleary coins the phrase “investment stampede” to capture the seismic shifts at work. The sector is growing fast – too fast – at 15% per annum, with a pipeline investment of $174 billion. Global demand especially from Asia has fuelled this boom. Current economic returns for the mining corporations and their shareholders are staggering.

In August 2011 BHP announced an annual net profit of $23.5 billion, while earlier in the year Rio Tinto had announced an annual profit of $14.3 billion.

Cleary’s book analyses an array of adverse impacts resulting from an investment stampede, including the growth of fly-in, fly-out (FIFO) workforces. Until the 1970s, mining leases tended to be issued by governments subject to conditions that companies build or substantially finance local community infrastructure, including housing, streets, transport, schools, hospitals and recreation facilities. Townships and communities went hand in hand with mining development.

Not any more. The haste of this extraction process has become increasingly reliant on a continuous production cycle of 12-hour shifts, seven days a week, and one increasingly reliant on fly-in, fly-out or drive-in, drive-out (non-resident) workers who typically work block rosters, and reside in work camps adjacent to existing rural communities.

There are estimated to be around 150,000 non-resident workers directly employed by the resources sector, anticipated to rise to around 200,000 by 2015, but no government body appears to be counting and projected growth is equally elusive.

This is an odd oversight given the rapid growth of reliance on non-resident workers in the resources sector carries significant impacts for individual workers and their families and host communities, as evidenced by the many submissions to the Australian Parliament House inquiry into FIFO/DIDO work practices, chaired by the Independent MP Tony Windsor. Some of the significant impacts include:

- A sudden influx in high risk populations (young single males with large disposable incomes) exacerbating crime and alcohol-related social disorder problems

- The creation of new lucrative unregulated drug markets and markets in commercial sex work.

- Rises in traffic congestion and road accidents.

- Stretch on infrastructure.

- The erosion of community wellbeing.

- Heightened risk of protracted social protest over coal-seam gas extraction.

- Ongoing widespread social protest against the erection of camps in close proximity to established rural communities.

- Increasing burden on local services.

- Soaring housing costs and other local costs of living

- “Fly over effects” on the local economy, and an ever-decreasing permanent resident workforce

- Increasing rates of staff turnover,

- Reversal of the trend of women entering the mining industry (down from 15.7 to 12.6% according to the most recent ABS statistics)

- Increases in the average hours worked each week exacerbating fatigue related car accidents and work injury as they commute either end of work cycles than in the workplace (an average of hours 45 hours as at August 2011, with 1 in 3 working over 60 hours per week).

These impacts undermine the long-term sustainable community development of rural Australia. It is troubling therefore that dramatic socio-demographic processes have been unleashed by this boom without concerted attempts to accurately research, measure or account for the numbers of non-resident workers involved and their nation-changing impact on the Australian society and economy.

Just as the number of non-resident workers is not being researched or counted, Cleary draws our attention to how the rapid depletion of natural non-renewable resources is not being counted either. Again, the long term social and environmental costs, including the time value of Australia’s natural resources and the opportunity costs of squandering them through an investment stampede are not being measured.

Instead, the gaze of most state politicians in particular has been transfixed on the short-term economic benefits shared by so few. Cleary draws attention to the dominance of a short-term economic view which frames the current resources boom – a view to which Kirchner appears wedded.

The real challenge for a government of and for the people – and not just a government at the beck and call and in the pocket of the powerful mining industry lobby – is to recalibrate the frame of reference for assessing and responding to the social and ecological impacts of the mining boom in the long term interests of the nation.

The corporate power of the mining industry, especially to lobby governments, state and commonwealth to influence policy making in Australia is alarming. As Cleary points out, “Not only did the miners change the prime minister and change government policy, they went on to brag about how their coup had stopped similar schemes from spreading around the world.”

State governments who grant mining licenses and regulate the industry also earn a share of the minerals extracted through royalties. Last year Queensland and Western Australian governments collected around $6 billion.

The Queensland government’s endorsement of the BHP Billiton Mitsubishi Alliance proposal at Moranbah to allow up 100% of workers to be non-resident is a more recent example of Cleary’s complaint about the impact of corporate power. It even contradicts Queensland’s own resource sector housing policy that workers should be allowed the choice where the live and work industry. The Moranbah mining community, with its long history of communal solidarity, is now destined to become surrounded by thousands of non-resident workers housed in dongas.

While the Queensland government introduced social impact assessment processes as part of the Environmental Impact Assessment approval process in Sept 2010 in part to address these concerns, it has failed to regulate the long term cumulative impacts of resource development. Why? State governments have a fundamental conflict of interest in setting themselves up as the arbiters in disputes over access to agricultural land, the granters of exploration licenses and the approvers of environmental and social impact statements, precursors to project development consent from which royalty payment to the state flow

Cleary’s book offers a much needed critique of the collision of self-interest between state governments and mining companies which both profit handsomely from the speedy extraction of resources.

Given the state governments’ conflict of interest and susceptibility to being courted by corporate power, the need for a commonwealth power to over-ride state powers in the interests of the more effective long-term regulation of the mining industry is long overdue. This week, Australia got one thanks the insistence of independent MPs Tony Windsor and Rob Oakeshott, who supported the Mineral Resources Rent Tax (MRRT) in return for the overhaul of the environmental approval processes and legislation.

Given the state governments’ conflict of interest and susceptibility to being courted by corporate power, the need for a commonwealth power to over-ride state powers in the interests of the more effective long-term regulation of the mining industry is long overdue. This week, Australia got one thanks the insistence of independent MPs Tony Windsor and Rob Oakeshott, who supported the Mineral Resources Rent Tax (MRRT) in return for the overhaul of the environmental approval processes and legislation.

Too Much Luck can be credited for fanning the shift in public opinion and political climate in support of the MRRT. We are at a critical moment in the boom, when strong, not weak, Australian Government leadership through the policy-making processes of federalism are absolutely vital, if, to use one of Cleary’s metaphors, Australia is not to look like Nauru, “but on a continental scale”.

How ironic. A party that poses as the vanguard of democratic reform denies its own membership the chance of greater democratic participation. Why?

How ironic. A party that poses as the vanguard of democratic reform denies its own membership the chance of greater democratic participation. Why?

By upwards engineering population growth, the Victorian and Australian Governments are showing disregard of "ultimate deprivation" and leaving "future generations with the task of rationing energy, oil and food..."

By upwards engineering population growth, the Victorian and Australian Governments are showing disregard of "ultimate deprivation" and leaving "future generations with the task of rationing energy, oil and food..."

The way The Australian writes him up, Tim Flannery, who once wrote so articulately in defense of our land and its ecology and our place in it, now seems reduced to a quasi-apologist for extreme mining technologies. The Australian writes in such an unbalanced way. See also

The way The Australian writes him up, Tim Flannery, who once wrote so articulately in defense of our land and its ecology and our place in it, now seems reduced to a quasi-apologist for extreme mining technologies. The Australian writes in such an unbalanced way. See also  Your ABC will be giving yet more air-space to commercial growth lobbyists who will be spruiking at the Wheeler Center tonight. Publicity for the event actually claims that high density living is "great for the environment." In fact, the Australian Conservation Foundation's Consumption Atlas shows that greenhouse gas emissions of those living in high-density areas are greater than for those living in low-density areas. An analysis of the data shows that the average carbon dioxide equivalent emission of the high-density core areas of Australian cities is 27.9 tons per person whereas that for the low-density outer areas is 17.5 tons per person. (Free Event TONIGHT 12 OCT 2011.)

Your ABC will be giving yet more air-space to commercial growth lobbyists who will be spruiking at the Wheeler Center tonight. Publicity for the event actually claims that high density living is "great for the environment." In fact, the Australian Conservation Foundation's Consumption Atlas shows that greenhouse gas emissions of those living in high-density areas are greater than for those living in low-density areas. An analysis of the data shows that the average carbon dioxide equivalent emission of the high-density core areas of Australian cities is 27.9 tons per person whereas that for the low-density outer areas is 17.5 tons per person. (Free Event TONIGHT 12 OCT 2011.)

Participants were shocked recently to hear Ms Prue Digby, Deputy Secretary, Planning and Local Government, Department of Planning and Community Development include in her paper on "housing a growing population" a section on "eliminating the NIMBY culture" at the Informa Australia "Population Australia - 2050 Summit." Article by Julianne Bell.

Participants were shocked recently to hear Ms Prue Digby, Deputy Secretary, Planning and Local Government, Department of Planning and Community Development include in her paper on "housing a growing population" a section on "eliminating the NIMBY culture" at the Informa Australia "Population Australia - 2050 Summit." Article by Julianne Bell.

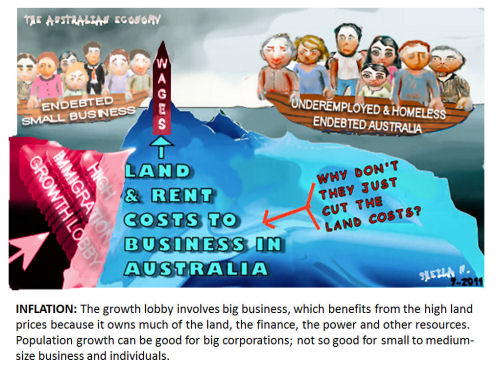

Why doesn't the government cut land costs? High costs of land, and the resources it carries - energy and water - are responsible for our failing economy. The greatest costs to small and medium-sized businesses are the rents they pay for their shops, warehouses, and factories. The greatest costs to workers are the rents they pay for personal accommodation. Small and medium-sized businesses pay both for their business premises and for their personal accommodation. Manufacturing in Australia is losing out to high rents and housing costs. Wages must go up to satisfy the malignant effect of land-speculation, which government continues to encourage against our common welfare. But, why don't they just cut the land-costs? Stop pushing up property prices by reducing immigration and you won't have to put wages up. Business will become competitive on the world market again, because most of its profits won't go on rent of premises. Let's get rid of the property developers. Let's outlaw land speculation. [Title changed from "Cut land-costs, not wages. Down with property developers, Up with workers!" on 9 Oct 2011.]

Why doesn't the government cut land costs? High costs of land, and the resources it carries - energy and water - are responsible for our failing economy. The greatest costs to small and medium-sized businesses are the rents they pay for their shops, warehouses, and factories. The greatest costs to workers are the rents they pay for personal accommodation. Small and medium-sized businesses pay both for their business premises and for their personal accommodation. Manufacturing in Australia is losing out to high rents and housing costs. Wages must go up to satisfy the malignant effect of land-speculation, which government continues to encourage against our common welfare. But, why don't they just cut the land-costs? Stop pushing up property prices by reducing immigration and you won't have to put wages up. Business will become competitive on the world market again, because most of its profits won't go on rent of premises. Let's get rid of the property developers. Let's outlaw land speculation. [Title changed from "Cut land-costs, not wages. Down with property developers, Up with workers!" on 9 Oct 2011.]

In a brilliant new paper released this morning, Labor MP Kelvin Thomson has proposed his "Witches' Hats" theory of government -- a theory that places central importance on rates of population growth.

In a brilliant new paper released this morning, Labor MP Kelvin Thomson has proposed his "Witches' Hats" theory of government -- a theory that places central importance on rates of population growth. The Centre for Population and Urban Research (CPUR) has recently released a major new report on immigration and on Australia's alleged need for labour. It shows that there is no real problem with supplying labour for the Resources Boom -- even if you accept the government's assumption that we need to export our resources as fast as possible.

The Centre for Population and Urban Research (CPUR) has recently released a major new report on immigration and on Australia's alleged need for labour. It shows that there is no real problem with supplying labour for the Resources Boom -- even if you accept the government's assumption that we need to export our resources as fast as possible.

An article in the Australian,

An article in the Australian,  FORUM NOW CLOSED, SORRY! But you can use Tony Boys'

FORUM NOW CLOSED, SORRY! But you can use Tony Boys'  The Age is a constant source of propaganda for population growth in Melbourne. Jake Niall's article today is another flagrant example. Melbournians need strong minds and hearts to fight back against their runaway parliaments and reclaim their natural rights to self-government.

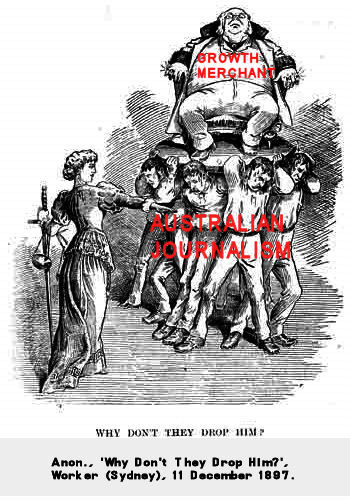

The Age is a constant source of propaganda for population growth in Melbourne. Jake Niall's article today is another flagrant example. Melbournians need strong minds and hearts to fight back against their runaway parliaments and reclaim their natural rights to self-government.  Age Sports-writer Jake Niall promotes the thinnest of arguments for overpopulating Melbourne as if they had real authority, on behalf of The Age, Melbourne's newspaper for the middle classes. The Age owns a massive international property dot com and represents a moneyed power-elite that relies on overpopulating Melbourne against residents' and electors' wishes and all commonsense. Its role seems to be to suppress protest through the massive weight of continuous propaganda, whilst maintaining a thin pretence of counterbalance by publishing mildly dissenting letters to the editor from time to time.

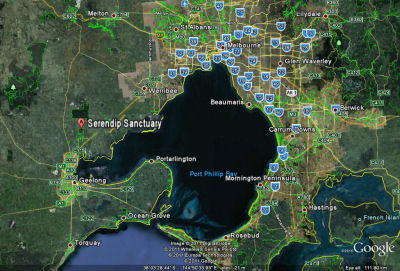

Age Sports-writer Jake Niall promotes the thinnest of arguments for overpopulating Melbourne as if they had real authority, on behalf of The Age, Melbourne's newspaper for the middle classes. The Age owns a massive international property dot com and represents a moneyed power-elite that relies on overpopulating Melbourne against residents' and electors' wishes and all commonsense. Its role seems to be to suppress protest through the massive weight of continuous propaganda, whilst maintaining a thin pretence of counterbalance by publishing mildly dissenting letters to the editor from time to time. Approval to rezone the rural land opposite Serendip Sanctuary, Lara, near Geelong, sets a dangerous precedent for open slather development that places the wildlife protected there at risk and flies in the face of democracy. The Sanctuary is internationally recognised for successfully breeding captive species such as Brolga, Musk and Freckled Duck and now the Eastern Barred Bandicoot, which is on the brink of extinction. Serendip forms an important wildlife corridor between the You Yangs Regional Park and Brisbane National Park through agricultural land and the sprawl of Greater Melbourne as it spreads to meet the regional city of Geelong.

Approval to rezone the rural land opposite Serendip Sanctuary, Lara, near Geelong, sets a dangerous precedent for open slather development that places the wildlife protected there at risk and flies in the face of democracy. The Sanctuary is internationally recognised for successfully breeding captive species such as Brolga, Musk and Freckled Duck and now the Eastern Barred Bandicoot, which is on the brink of extinction. Serendip forms an important wildlife corridor between the You Yangs Regional Park and Brisbane National Park through agricultural land and the sprawl of Greater Melbourne as it spreads to meet the regional city of Geelong. Why do Victorians and other Australians have to keep fighting over and over again to protect their rights from the very people who are supposed to be looking after their rights?

Why do Victorians and other Australians have to keep fighting over and over again to protect their rights from the very people who are supposed to be looking after their rights? The Serendip corridor ultimately leads, via the You Yangs Regional Park to the Brisbane Ranges National Park, which is a haven for koalas, which are daily losing their habitat to the unprecedented amount of development in Victoria and other states.

The Serendip corridor ultimately leads, via the You Yangs Regional Park to the Brisbane Ranges National Park, which is a haven for koalas, which are daily losing their habitat to the unprecedented amount of development in Victoria and other states.  Serendip Sanctuary is just 45 minutes to the west of Melbourne but visitors will find that they are immediately amongst wild kangaroos and native birds, such as the animated honeyeaters and screeching cockatoos. The lake is the home of crowds of waterbirds. These waterbirds include the magnificent brolgas, celebrated in Aboriginal dance, now rarely seen by Australians.

Serendip Sanctuary is just 45 minutes to the west of Melbourne but visitors will find that they are immediately amongst wild kangaroos and native birds, such as the animated honeyeaters and screeching cockatoos. The lake is the home of crowds of waterbirds. These waterbirds include the magnificent brolgas, celebrated in Aboriginal dance, now rarely seen by Australians.  The Canadian federal election cries out for an alternative to BAU growthism. It cries out for a party which would present a coherent and distinctive alternative to the system of economic growth. Canadians need a place on the ballot where they can mark an "X" beside "no more growth". In fact they need an opportunity for vote for "de-growth". But the Green Party of Canada is not providing them with that opportunity or alternative. Instead, what they are providing is meaningless rhetoric and platitudes. Shall we lend credence to their approach by voting for them? Shall we allow them to say that they have our support for their direction? Shall we allow them to say, after receiving our vote, that they have a mandate to push for hyper immigration and a foreign aid policy that would continue to promote global overpopulation? I say no. I say that casting a vote can sometimes be worse than spoiling a ballot. There are many things one can do to promote change that voting in a sham election. Writing, petitioning, demonstrating and educating the grassroots come to mind.

The Canadian federal election cries out for an alternative to BAU growthism. It cries out for a party which would present a coherent and distinctive alternative to the system of economic growth. Canadians need a place on the ballot where they can mark an "X" beside "no more growth". In fact they need an opportunity for vote for "de-growth". But the Green Party of Canada is not providing them with that opportunity or alternative. Instead, what they are providing is meaningless rhetoric and platitudes. Shall we lend credence to their approach by voting for them? Shall we allow them to say that they have our support for their direction? Shall we allow them to say, after receiving our vote, that they have a mandate to push for hyper immigration and a foreign aid policy that would continue to promote global overpopulation? I say no. I say that casting a vote can sometimes be worse than spoiling a ballot. There are many things one can do to promote change that voting in a sham election. Writing, petitioning, demonstrating and educating the grassroots come to mind. The Canadian federal election is upon us and the Green Party claims to offer a "significantly different approach to governance" (see below). Really? Let's take a look:

The Canadian federal election is upon us and the Green Party claims to offer a "significantly different approach to governance" (see below). Really? Let's take a look: Big capitalism and the population growth lobby force people to live in dangerously risky conditions which by tradition they used to avoid. Only by returning power to the citizens via local and regional governments can we stop the population growth and the constant increase in accidents, corruption and diminished quality of life. To return power to local citizens, we need better laws to stop media ownership residing in so very few hands and being allowed to be the default 'information' conduite for government and the principle means of publicising candidates for election.

Big capitalism and the population growth lobby force people to live in dangerously risky conditions which by tradition they used to avoid. Only by returning power to the citizens via local and regional governments can we stop the population growth and the constant increase in accidents, corruption and diminished quality of life. To return power to local citizens, we need better laws to stop media ownership residing in so very few hands and being allowed to be the default 'information' conduite for government and the principle means of publicising candidates for election.

I was moved to investigate further when on April 5th candobetter.net received an anonymous comment, entitled, "Koala left clinging to a tree after land clearing."

I was moved to investigate further when on April 5th candobetter.net received an anonymous comment, entitled, "Koala left clinging to a tree after land clearing."

You hear people like Rob Adams and Marcus Spiller saying there is nothing you can do about population growth in Victoria and Australia. Wrong. For a start the government should cancel the

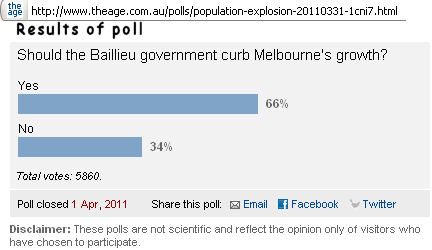

You hear people like Rob Adams and Marcus Spiller saying there is nothing you can do about population growth in Victoria and Australia. Wrong. For a start the government should cancel the  Results of Melbourne population poll, added to this article on 16 April 2011.

Results of Melbourne population poll, added to this article on 16 April 2011.

Fear of 'boat-people' coming in massive numbers will continue to be stoked by the Murdoch and Fairfax media and tv and radio. Some people will therefore continue to fear the Greens as agents of the 'boat-people' bogeyman. Others will fear them as politicians who would see their countrymen dispossessed by a strange and unaccountable rhetoric.

Fear of 'boat-people' coming in massive numbers will continue to be stoked by the Murdoch and Fairfax media and tv and radio. Some people will therefore continue to fear the Greens as agents of the 'boat-people' bogeyman. Others will fear them as politicians who would see their countrymen dispossessed by a strange and unaccountable rhetoric.

First the Fraser Institute was named Canada's top "Think Tank" and among the best of 25 Think Tanks in the world. Now Vancouver has been named the world's most livable city. At this rate, I suppose that soon it will be named the driest city on the continent. Who is making these judgments, a Queensland politician? Here's a tip. Before you rave about Vancouver, try living there on an average wage. Good luck.

First the Fraser Institute was named Canada's top "Think Tank" and among the best of 25 Think Tanks in the world. Now Vancouver has been named the world's most livable city. At this rate, I suppose that soon it will be named the driest city on the continent. Who is making these judgments, a Queensland politician? Here's a tip. Before you rave about Vancouver, try living there on an average wage. Good luck.

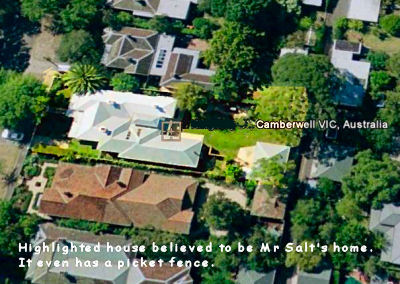

Committee for Melbourne growthers are scraping the bottom of the barrel looking for new ways to get people to move to the hated high-rises the property development lobby has planned all over Melbourne. Mary Drost says, "Both Andrew McLeod and Bernard Salt are obsessed with growth. It is exactly this growth that is making Melbourne less liveable as everything is overstretched." Jill Quirk asks, "I wonder if Salt and MacLeod think widows Jeannie Pratt or Elisabeth Murdoch should vacate their premises for a flat in an "activity centre" or is just people who inhabit more modest post war triple fronted accommodation who are being asked to move over ?"

Committee for Melbourne growthers are scraping the bottom of the barrel looking for new ways to get people to move to the hated high-rises the property development lobby has planned all over Melbourne. Mary Drost says, "Both Andrew McLeod and Bernard Salt are obsessed with growth. It is exactly this growth that is making Melbourne less liveable as everything is overstretched." Jill Quirk asks, "I wonder if Salt and MacLeod think widows Jeannie Pratt or Elisabeth Murdoch should vacate their premises for a flat in an "activity centre" or is just people who inhabit more modest post war triple fronted accommodation who are being asked to move over ?"

The market for Vancouver real estate has gone global in a big way. The first wave of rich Chinese buyers came in the 80s and 90s as the impending transfer of Hong Kong to mainland rule approached, and the demolition of modest homes on the west side in favour of mega-houses transformed the city. But now China itself has spawned an even bigger reservoir of affluence that is looking for an investment outlet and finding it in Vancouver property. This will complete the process of dispossession that began three decades ago. Even higher density and higher property taxes and rents will combine to make life in this city---a city frequently held up as a model of sensible planning in Australia---tenuous and stressful at best. But stayed tuned. The property bubble will burst, and these investors and the realtors who cater to them will take a well-deserved beating.

The market for Vancouver real estate has gone global in a big way. The first wave of rich Chinese buyers came in the 80s and 90s as the impending transfer of Hong Kong to mainland rule approached, and the demolition of modest homes on the west side in favour of mega-houses transformed the city. But now China itself has spawned an even bigger reservoir of affluence that is looking for an investment outlet and finding it in Vancouver property. This will complete the process of dispossession that began three decades ago. Even higher density and higher property taxes and rents will combine to make life in this city---a city frequently held up as a model of sensible planning in Australia---tenuous and stressful at best. But stayed tuned. The property bubble will burst, and these investors and the realtors who cater to them will take a well-deserved beating.

North American children of my older brothers' generation knew about The Shadow He was the heroic vigilante crime fighter of pulp fiction fame who made his presence felt in comic books, movies and most poignantly on radio, the centre piece of family entertainment. By the time I came of age as a boy in the late fifties, he had left the stage, but not in my imagination---- my brother Al made sure of that. He would hide in my bedroom closet as I went to sleep then awake me with a chilling rendition: Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men! Only The Shadow knows! He knows that the weed of crime bears bitter fruit! I'll be around every corner---in every closet----in every room, as inevitable as your guilty conscience." Then he would follow up with a sinister laugh, "Ha Ha Haw!" To this day, I have fantasized about reprising that role, only this time as a corporate crime fighter, a shadow to the Growth Lobby, and those in the environmental movement who collaborate with them.

North American children of my older brothers' generation knew about The Shadow He was the heroic vigilante crime fighter of pulp fiction fame who made his presence felt in comic books, movies and most poignantly on radio, the centre piece of family entertainment. By the time I came of age as a boy in the late fifties, he had left the stage, but not in my imagination---- my brother Al made sure of that. He would hide in my bedroom closet as I went to sleep then awake me with a chilling rendition: Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men! Only The Shadow knows! He knows that the weed of crime bears bitter fruit! I'll be around every corner---in every closet----in every room, as inevitable as your guilty conscience." Then he would follow up with a sinister laugh, "Ha Ha Haw!" To this day, I have fantasized about reprising that role, only this time as a corporate crime fighter, a shadow to the Growth Lobby, and those in the environmental movement who collaborate with them.

In terms of numbers, Green-Left ideologues are marginal. But they punch far above their weight. Their mission is plant preconceptions about eco-Malthusians in the minds of grass roots environmentalists and those few in the media would invite our input. Left unchallenged, this bad rap becomes conventional wisdom, and doors continue to slam in our faces. And these New McCarthyists know it. It is time we gave them a dose of their own medicine. We must expose their corporate funding sources and ask the obvious questions. Whose agenda are THEY serving? Whose interest is served by open borders? Are not the "eco-socialists" and "green" Trots Wall Street's useful idiots?

In terms of numbers, Green-Left ideologues are marginal. But they punch far above their weight. Their mission is plant preconceptions about eco-Malthusians in the minds of grass roots environmentalists and those few in the media would invite our input. Left unchallenged, this bad rap becomes conventional wisdom, and doors continue to slam in our faces. And these New McCarthyists know it. It is time we gave them a dose of their own medicine. We must expose their corporate funding sources and ask the obvious questions. Whose agenda are THEY serving? Whose interest is served by open borders? Are not the "eco-socialists" and "green" Trots Wall Street's useful idiots?

Frodo still has pellets in the stomach. Condemnation from the Queensland government is rather shallow when biodiversity in southeast Queensland is under pressure from habitat loss primarily due to increased urbanisation, driven by population growth, a fact stated in the State Government’s State of the Region (SEQ) report.

Frodo still has pellets in the stomach. Condemnation from the Queensland government is rather shallow when biodiversity in southeast Queensland is under pressure from habitat loss primarily due to increased urbanisation, driven by population growth, a fact stated in the State Government’s State of the Region (SEQ) report. Film and text of speech now available inside article. Speech given at Planning Backlash Forum of 7 Nov 2010: "In July last year I made a 22 page submission to the Victorian Government titled “5 Million is too many: Securing the Social and Environmental Future of Melbourne”. So given that I think 5 million would be too many, you can imagine what I think of the idea of doubling Melbourne’s population to 8 million. Melbourne’s population is growing on a scale not seen in Australia before, swelling by almost 150,000 people in the last two years. Melbourne’s population is growing by more than 200 people per day, 1500 per week, 75,000 per year. This is much faster than all other major Australian cities. It will give us another million people in 15 years."

Film and text of speech now available inside article. Speech given at Planning Backlash Forum of 7 Nov 2010: "In July last year I made a 22 page submission to the Victorian Government titled “5 Million is too many: Securing the Social and Environmental Future of Melbourne”. So given that I think 5 million would be too many, you can imagine what I think of the idea of doubling Melbourne’s population to 8 million. Melbourne’s population is growing on a scale not seen in Australia before, swelling by almost 150,000 people in the last two years. Melbourne’s population is growing by more than 200 people per day, 1500 per week, 75,000 per year. This is much faster than all other major Australian cities. It will give us another million people in 15 years."

There is an unrelenting media campaign to tell Canadians that we must grow our population. We need more babies and more immigrants or very bad things will happen. But there are voices that question this assumption. They are heard on the streets, in the pubs and at the dining room table. But they are seldom heard in the media. Especially not on the airways of the CBC, that vehicle of growthist PC propaganda which all taxpayers are forced to endow.

There is an unrelenting media campaign to tell Canadians that we must grow our population. We need more babies and more immigrants or very bad things will happen. But there are voices that question this assumption. They are heard on the streets, in the pubs and at the dining room table. But they are seldom heard in the media. Especially not on the airways of the CBC, that vehicle of growthist PC propaganda which all taxpayers are forced to endow.

Recent comments