Over the next 40 years, Melbourne's is to be projected, or force-fed, to grow geographically and in population.

The discussion paper is how to plan for that growth and miraculously at the same time “ensuring our city remains one of the most diverse, distinctive and liveable cities in the world”. The “discussion” is not about democratically deciding whether we want the growth or not, but propaganda that endorses the benefits of growth, and how to implement it. It's a long term vision, of continuous growth- whether we want it or not!

Melbourne, Let's Talk about the Future, Oct 2012

Over the next 40 years, Melbourne's is to be projected, or force-fed, to grow geographically and in population.

The discussion paper is how to plan for that growth and miraculously at the same time “ensuring our city remains one of the most diverse, distinctive and liveable cities in the world”. The “discussion” is not about democratically deciding whether we want the growth or not, but propaganda that endorses the benefits of growth, and how to implement it. It's a long term vision, of continuous growth- whether we want it or not!

The Victorian government wants conversation with the community on how to respond to population growth, economic challenges and profound demographic changes that will be socially engineered through record high levels of immigration – and “natural” growth. On one hand we are fortunate that our culture is not one that endorses large families, or the growth of tribes. Our population growth rate is a government-based, an economic model, one that can easily be addressed – politically.

Benefit of growth

This discussion is about people’s quality of life. It is also about finding new ways to share the “benefits of growth and investment, and the responsibilities of delivering these benefits”. It doesn't actually say what the “benefits” of growth will be – other than for businesses and the property industries. While the growth-based economic model has served us well in the past, but is no longer appropriate in a planet, a nation, of diminishing and finite resources.

While accommodating this growth, we are suppose to have “choices about where

we live and work, how we travel to and from work and what we do in our leisure time – these are all influenced by how we plan and manage the growth of our city”. On the contrary, the greater our population grows, the less choices we have about where we live, housing alternatives, how we travel, our leisure time, and the costs of living. Living in the more “affordable” fringe areas of Melbourne means having a income per year of at least 70,000, but this means being denied public transport, and more reliance on cars.

What benefits?

We face many challenges and choices if Melburnians are to continue to share the benefits of growth and development..... Urban renewal can have many positive effects. It can replenished housing stock and improve quality; it can increase density and reduce sprawl; it can deliver economic benefits and improve the global economic competitiveness of a city’s centre. It may improve social opportunities, and it may also improve safety through passive surveillance.

Planning for our future is not about the abstract – it is about people’s quality of life. It is also about finding new ways to share the benefits of growth and investment, and the responsibilities of delivering these benefits.

Growth is not a pre-condition for improving quality of housing. Increasing housing density is not a benefit, and reducing urban sprawl is not guaranteed as our city has been growing outward as well as upward. People still prefer to live in the privacy of a house, with a garden and amenities despite being in far-flung suburbs. The “economic benefits” are not for the public, but for those associated with the housing industry, and mega-stores and businesses.

The discussion paper on planning Melbourne's future, (The Age, 26/10) released by the Baillieu government, warns that housing has become less affordable, pushing people further out to where there are fewer services and jobs.

The report also says that in just two decades the number of people fully owning a home in Melbourne has dropped from 40 to 30 per cent and the number of people paying off a mortgage has risen from 30 to 35 per cent. Households on Melbourne's median income of $70,300 a year were being blocked from the city's housing market with few suburbs now affordable. “Medium” income means that there are many people living on under $70k per year and are locked out of home ownership, even if the fringes of Melbourne.

More population growth will only add to the squeeze on affordable housing, increase land prices, push up the demand for public housing and force more people to “choose” high density living.

No “sacred cows”

Jennifer Cunich, from the Property Council, welcomed the planning discussion paper and said there should be no ''sacred cows in this important community debate''. The “sacred cow” that needs to be sent to slaughter it the myth that ongoing population growth in Melbourne will give us any benefits.

The only beneficiaries will be the property developers, banks and investors.

There appears to be little inclination of governments and businesses to abandon their enthusiasm for the "sacred cow" of their growth-based economic model - something inappropriate in a world of finite and diminishing resources.

The reports includes:

....by 2050, Melbourne's population will likely be between 5.6 and 6.4 million.

Another recent document from the Planning Department (DPCD)

“Victoria in the future: 2012 - Population and household projections 2011 – 2031 for Victoria and its Regions” states that:

Over the 40 years to 2051, Victoria’s population is projected to increase by 3.2 million to 8.7 million. Over the same period, Melbourne’s population is expected to grow to 6.5 million, while regional Victoria is projected to grow to 2.3 million. The “projected” growth will obviously be controversial, so they dose out their growth plans in small, digestible doses!

....a possible new airport in the south west of Melbourne, serving one third of Victoria's population. There is adequate capacity to increase the number of aircraft flying into Melbourne ...

A new airport denies peak oil, and the increasing costs of aviation fuel. According to a graph in the Sydney Airport Master Plan of 2009, there should have been 42.5 million passengers at Kingsford-Smith airport in 2012. But extrapolating growth data up to August this year, passenger traffic in 2012 is likely to be just 36.3 million or 85% of this estimate. While international traffic grew continuously, domestic traffic stayed practically flat at around 24 million pa since 2010.

While the “immigration” debate rests on asylum seekers arriving by boat, the vast hoards of new arrivals arrive at air ports – without debate! But jet travel is also something that does and will always depend on liquid fuel, so it is likely that constraints in the liquid fuel supply will directly show through into constraints in jet travel. Fossil fuels are being relentlessly depleted, it takes an inexorable amount energy to produce them, resulting in a cumulative and rising energy demand overall.

A policy U-turn to limit the use of biofuels comes after studies cast doubt on the carbon dioxide emissions savings from using crop-based fuels, and following a poor harvest in key grain growing regions that pushed up prices and revived fears of food shortages. The amount of land available worldwide that is not suitable for agricultural use is currently estimated at anywhere between 600 million and 3.5 billion hectares, according to the Aviation Initiative for Renewable Energy in Germany (AIREG).

A “20 minute” city, with jobs and services within 20 minutes of home..

Congestion significantly impacts Victoria's productivity and liveability. In Melbourne, both the Commonwealth Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics and the Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission estimated the

cost of congestion in 2005-06 was in the billions of dollars and both institutions expect this to double in the next 10 to 15 years.

Services need to be provided in a more timely manner to urban growth areas and established outer areas of Melbourne. ...

More freeways and roads will simply attract more cars and traffic, and the cost of providing for these “services”, always failing to keep abreast to growth, need to be funded at a time households are already suffering from high costs of living.

The debate about infill housing in Melbourne must move beyond the impact of villa units on suburban streets and address how we can deliver the diverse housing, in the right locations, at a reasonable price. Rather than “diverse” housing, we are seeing more cookie-cutter developments, and more ubiquitous high density apartments and sky-scrapers. The rising costs of land will prohibit “reasonable” prices for housing. More people will be forced to “choose” higher density living and smaller living compartments.

Melbourne is a suburban city and that will not change. The environmental performance of its suburbs can be dramatically improved. The last decades have seem Melbourne not improve, but decline. TAFE funding has been cut, schools are closing, public housing waiting lists are exploding, even for “urgent” cases. (10 years). Hospital funding is being cut, public transport is failing to keep up with demands, and our city is continually suffering from “shortages”. The costs of population growth are simply ignored.

shifting housing growth to towns and regional centres...

House prices cripple many families. Mortgage pressure is an increasing concern. Population pressure and densification produce ever-worsening traffic jams which merely add to the time parents spend away from home. Victoria’s regional house market yielded a stronger result over the past year than Melbourne’s. Over the past 12 months the regional increase was 8.5%, according to the REIV June quarter survey.

Across Victoria, there is also a large-scale population shift happening now with tens of thousands moving from the Wimmera, Mallee and Western District to regional centres such as Geelong, Ballarat and Bendigo. This is putting new pressure on services and infrastructure in those areas while other towns, districts and communities are drained of people and the economic lifeblood they need to thrive. There are massive gaps in public transport, community services and employment options on the urban fringe and in regional Victoria fueling increased demand for emergency assistance and financial support, and it is community and welfare organisations that are forced to fill the “service hole” created by the lack of investment.

People in these communities find it harder to cope with unaffordable housing, rising costs for utilities and other non-discretionary spending items – such as food, health care, education, and transport, the increased cost of which have a disproportionate impact on low-income households. Meanwhile, job losses in manufacturing and other sectors of the Victorian economy are starting to bite.

The ills of Melbourne are spreading out to regional areas, and Councils are under financial stress.

The most pressing issue facing councillors about to be elected to office in rural and regional areas is how best to protect ratepayers from the impact of the developing financial crisis in local government. Over the past few years nearly all rural and regional councils have become financially reliant on increasing rates and charges at about twice the pace of their metropolitan counterparts and sometimes up to five times CPI.

options for funding new infrastructure – such as user-pay tolls, asset sales, borrowing, and project-specific bonds..

A very detailed study for the former Bureau of Immigration Research found the net cost to government budgets for an annual migrant intake of 114,000 was well over $3 billion dollars, or about $34,500 (in 1992 dollars) per immigrant. (Mark O'Connor) So the existing population needs to spend at least $200,000 on infrastructure for each new person added to Australia. If this is not spent before the new people arrive, we get the congested roads, hospital queues, overcrowded trains that we see in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane.

Selling off more assets means more privatisation and higher costs, something that will only benefit the buyers and shareholders, not the public. Selling off capital assets that belong to the public for day to day running costs is not good business practice. It's an admission that the economic “benefits” of population growth fail to cover the costs.

creating a new metropolitan planning authority to guide development..

One option is to establish a metropolitan planning authority which, amongst other responsibilities, would coordinate relevant Government agencies in the timely delivery of city-shaping infrastructure and other projects of metropolitan significance.

Already we have too many tiers of planning, with public consultation and Councils giving approvals, then to have them rejected by VCAT. Another tier or “authority” will give one more storey of detachment from democratic input from those who carry the impacts the most – the public of Melbourne.

Environmental costs of population growth

Melbourne needs to be environmentally resilient. We need to be able to respond to changing environmental and climate conditions and ensure development does not undermine natural values.

We will need to use resources more efficiently and produce less waste.

City growth should be about expanding people’s choices and giving them the capabilities to exercise choices for a better life, while respecting the natural environment – on which we, future generations, and our native species depend.

Melbournians,due to overpopulation, already have a $24 billion bill for water from the desal plant!

On the contrary, The Baillieu Government's decision to scrap plans for the creation of vital habitat corridors for Victoria's endangered Southern Brown Bandicoot have angered conservation groups. "Obviously the Victorian Government has been captured by developers and is failing to take into account long-term conservation and community needs." VPNA

"The environmental side of growth planning in Victoria has become a shambles and is putting the credibility of the entire process under question," VPNA Executive Director Mr Ruchel said. The expansion of Melbourne's urban growth boundary will also include the clearing of critically endangered grassland and woodlands, as well as the establishment of large grassland reserves west of the city and 200m wildlife corridors on each side of creeks for to help protect Growling Grass Frog habitat.

Globally, city populations are expected to grow by five billion people and expand by 1.2 million square kilometers by 2030. Much of this expansion is forecast to occur in the tropics, which contain the bulk of the world's species.

Global population will expand to up to 10 billion people this century, with two billion additional people on the planet within 40 years, all needing food, water and shelter. Climate change will further wreak havoc on basic human needs. We have world-wide threats of "peaks" in energy, water, soils, fertilizers and species losses. it's obvious that growth - what served us well in the past - can't be a model for the future.

Matthew Guy and the Baillieu government, and our Federal government, seem to consider we can make growth policies in a vacuum, as if we live in a parallel universe of endless resources, untouched by Earth's limits.

Protecting future generations, an their quality of live

An Australia with a stable population promises a better and safer quality of life for our children and grandchildren, and secures more choices in the face of global threats and depletions. Although our current population is higher population than we should have, it is at least a population we can still plan for. It is logically impossible to plan for an indefinitely increasing population and ignoring the constraints, the limits to growth, will compromise us socially, environmentally and economically.

Monday 10 December Frankston Council will approve the design of the South East Water (SEW) high rise Office Block. The building is 8 -9 story high (potentially 10 in the future) and extends for an entire city block from Playne Street to Wells Street. Public space is being rapidly chewed up in Frankston. It lost its Central Park in the Town Centre to Gandel over ten years ago. It looks like losing the long planned Kananook Creek Boulevard (connecting the town centre to the waterfront) to a South East Water office tower and a new aquatic centre is swallowing up existing parklands. Another crucial issue is due process and secret deals.

Monday 10 December Frankston Council will approve the design of the South East Water (SEW) high rise Office Block. The building is 8 -9 story high (potentially 10 in the future) and extends for an entire city block from Playne Street to Wells Street. Public space is being rapidly chewed up in Frankston. It lost its Central Park in the Town Centre to Gandel over ten years ago. It looks like losing the long planned Kananook Creek Boulevard (connecting the town centre to the waterfront) to a South East Water office tower and a new aquatic centre is swallowing up existing parklands. Another crucial issue is due process and secret deals.

The new science of ecology will now describe animals as they really are---moral agents, not biological automatons. And as such, they are to be charged with a moral responsibility to constrain their cravings and live simply so that other animals like them can simply live. Or as they now say on St. Monbiot Island, “Be the reindeer you want the world to be.”

The new science of ecology will now describe animals as they really are---moral agents, not biological automatons. And as such, they are to be charged with a moral responsibility to constrain their cravings and live simply so that other animals like them can simply live. Or as they now say on St. Monbiot Island, “Be the reindeer you want the world to be.”

Just off the coast of Papua New Guinea there is a huge new 'deep sea mining' venture called Solwara 1 mine. University based environmental scientists in PNG and Australia are worried that the venture is largely experimental and that the entire venture is "out of its depth." They also say that intellectual Property Rights, community and environmental health in the Bismarck Seas and PNG’s Exclusive Economic Zone are inadequately addressed.

Just off the coast of Papua New Guinea there is a huge new 'deep sea mining' venture called Solwara 1 mine. University based environmental scientists in PNG and Australia are worried that the venture is largely experimental and that the entire venture is "out of its depth." They also say that intellectual Property Rights, community and environmental health in the Bismarck Seas and PNG’s Exclusive Economic Zone are inadequately addressed.

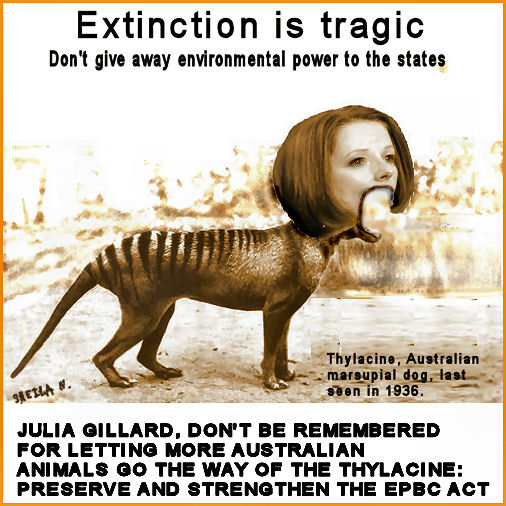

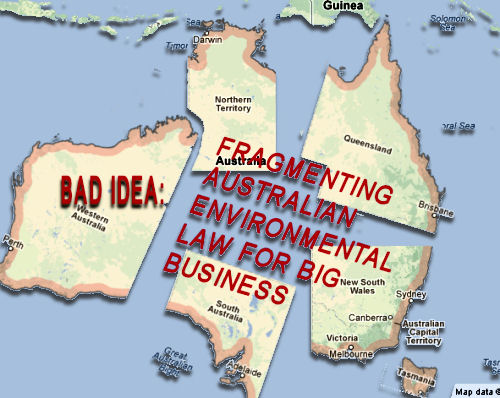

David Attenborough and other renowned conservation figures have urged PM Gillard to retain National Environment Powers. At the moment changes devolving major decision making to our growth-mad developer states are imminent. The writers of a letter to the Primeminister say that their concern arises particularly due to Australia being "one of a very few biologically mega-diverse developed countries on the face of this Earth. The array of natural ecosystems and their component species is simply breathtaking, making Australia one of the most important and exciting places in the world for the long-term conservation of biological diversity."

David Attenborough and other renowned conservation figures have urged PM Gillard to retain National Environment Powers. At the moment changes devolving major decision making to our growth-mad developer states are imminent. The writers of a letter to the Primeminister say that their concern arises particularly due to Australia being "one of a very few biologically mega-diverse developed countries on the face of this Earth. The array of natural ecosystems and their component species is simply breathtaking, making Australia one of the most important and exciting places in the world for the long-term conservation of biological diversity."

Kelvin Thomson, MP for Wills, has written to Prime Minister Gillard, asking her to consider and respond to the concerns of constituents about planned changes to the federal environment act. Have any other ministers done this? We would like to hear from them if so.

Kelvin Thomson, MP for Wills, has written to Prime Minister Gillard, asking her to consider and respond to the concerns of constituents about planned changes to the federal environment act. Have any other ministers done this? We would like to hear from them if so.  Federal Caucus has carried a motion to have the Caucus Live Animal Export Working Group develop a model for an Office of Animal Welfare. We know of two MPs who actively support this motion and would like to hear from any others. Kelvin Thomson and Melissa Parke, respectively MPs for Wills in Victoria and Fremantle in West Australia support this approach.

Federal Caucus has carried a motion to have the Caucus Live Animal Export Working Group develop a model for an Office of Animal Welfare. We know of two MPs who actively support this motion and would like to hear from any others. Kelvin Thomson and Melissa Parke, respectively MPs for Wills in Victoria and Fremantle in West Australia support this approach.

This Friday, 7 December, the Federal Government plans to give away environmental assessment authority to the states. Candobetter readers should take any opportunity they can to avoid this devolution of our already semi-toothless legislation. Here is an opportunity to add your signature to a petition. There is also a Get-up campaign. Readers are invited to let us know of any other actions they are taking.Links to petitions etc inside.

This Friday, 7 December, the Federal Government plans to give away environmental assessment authority to the states. Candobetter readers should take any opportunity they can to avoid this devolution of our already semi-toothless legislation. Here is an opportunity to add your signature to a petition. There is also a Get-up campaign. Readers are invited to let us know of any other actions they are taking.Links to petitions etc inside.

Not so livable Victoria - Melbourne rally calls on government to curb immigration and stop advertising for new settlers overseas for Victoria in view of environmental and amenity impacts of huge population

Not so livable Victoria - Melbourne rally calls on government to curb immigration and stop advertising for new settlers overseas for Victoria in view of environmental and amenity impacts of huge population

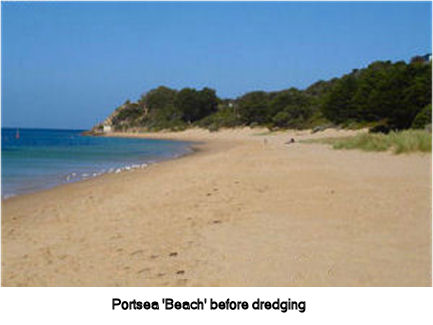

Join us at Portsea Pier at 12 Noon Tuesday 4th December. We’ll have a bucket of money that we’ll hand back to the PoMC when Portsea beach comes back.

Join us at Portsea Pier at 12 Noon Tuesday 4th December. We’ll have a bucket of money that we’ll hand back to the PoMC when Portsea beach comes back.

A left-wing environmentalist group opposed to all forms of racism and xenophobia has been able to get a national immigration referendum on the ballot in Switzerland.

A left-wing environmentalist group opposed to all forms of racism and xenophobia has been able to get a national immigration referendum on the ballot in Switzerland.

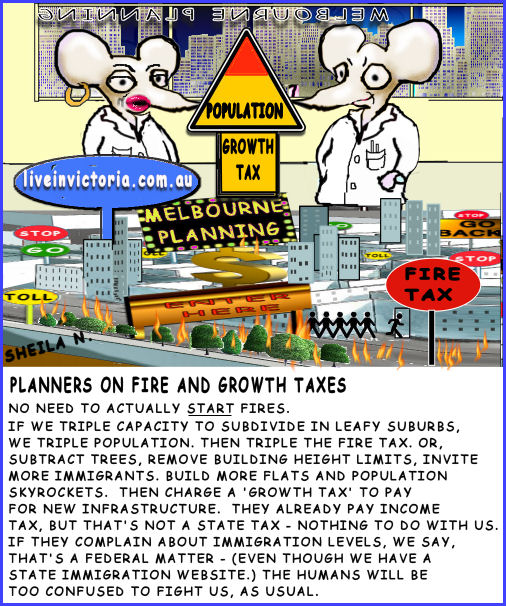

Fire taxes and people taxes - Are we seeing the genesis of what could well be the next tax imposition for the people of Victoria to pay for the population growth that the state forces on us?

Fire taxes and people taxes - Are we seeing the genesis of what could well be the next tax imposition for the people of Victoria to pay for the population growth that the state forces on us?

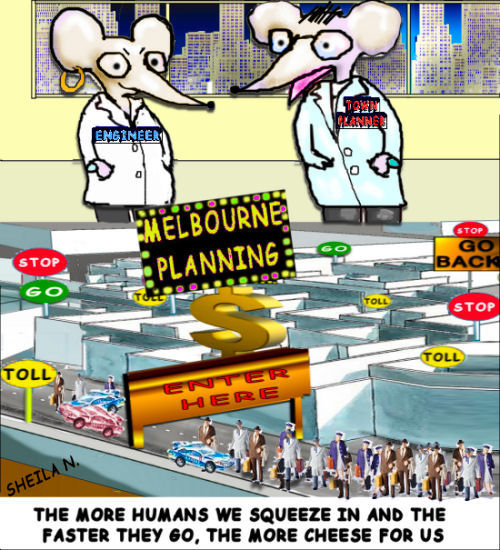

Is the Department of Planning in the Victorian State government vital to our lives or is it just part of endless population growth ? The Planning Department operates with a seemingly remarkable ignorance of the realities of resource (especially oil) depletion, some apprehension of climate change, scant reference to the environment, and no mention of creatures other than humans. Something funny's going on.

Is the Department of Planning in the Victorian State government vital to our lives or is it just part of endless population growth ? The Planning Department operates with a seemingly remarkable ignorance of the realities of resource (especially oil) depletion, some apprehension of climate change, scant reference to the environment, and no mention of creatures other than humans. Something funny's going on.

Kevin Rudd and Malcolm Turnbull like many other politicians seem to think of themselves as ideas men. Do we really need politicians with 'ideas' or are they a liability?

Kevin Rudd and Malcolm Turnbull like many other politicians seem to think of themselves as ideas men. Do we really need politicians with 'ideas' or are they a liability?

The consideration of the Planning Zones Review should have been referred to the Parliamentary Committee for Environment and Planning which has considerable resources to put the 2,000 submissions on the Parliamentary website and then record on Hansard the hearings of some of the submitters before the Parliamentary Committee.

The consideration of the Planning Zones Review should have been referred to the Parliamentary Committee for Environment and Planning which has considerable resources to put the 2,000 submissions on the Parliamentary website and then record on Hansard the hearings of some of the submitters before the Parliamentary Committee.

Community groups are making submissions on the Reformed Zones in Victoria. The government's zoning aims to increase commercial areas into residential areas in a serial manner and to intensify activity in the green wedges. The Department of Planning and Community Development has appointed a Ministerial Advisory Committee 'to review all submissions and provide advice back to the government', but the Chairman of the Committee is Geoff Underwood, who is prominent in the affairs of the Australian Population Institute (APop), which is officiated by professional developers and has the primary aim of promoting a huge population for Australia. What chances do robust submissions have with APop defining the parameters of planning in Victoria? See Planning Backlash submission inside.

Community groups are making submissions on the Reformed Zones in Victoria. The government's zoning aims to increase commercial areas into residential areas in a serial manner and to intensify activity in the green wedges. The Department of Planning and Community Development has appointed a Ministerial Advisory Committee 'to review all submissions and provide advice back to the government', but the Chairman of the Committee is Geoff Underwood, who is prominent in the affairs of the Australian Population Institute (APop), which is officiated by professional developers and has the primary aim of promoting a huge population for Australia. What chances do robust submissions have with APop defining the parameters of planning in Victoria? See Planning Backlash submission inside.

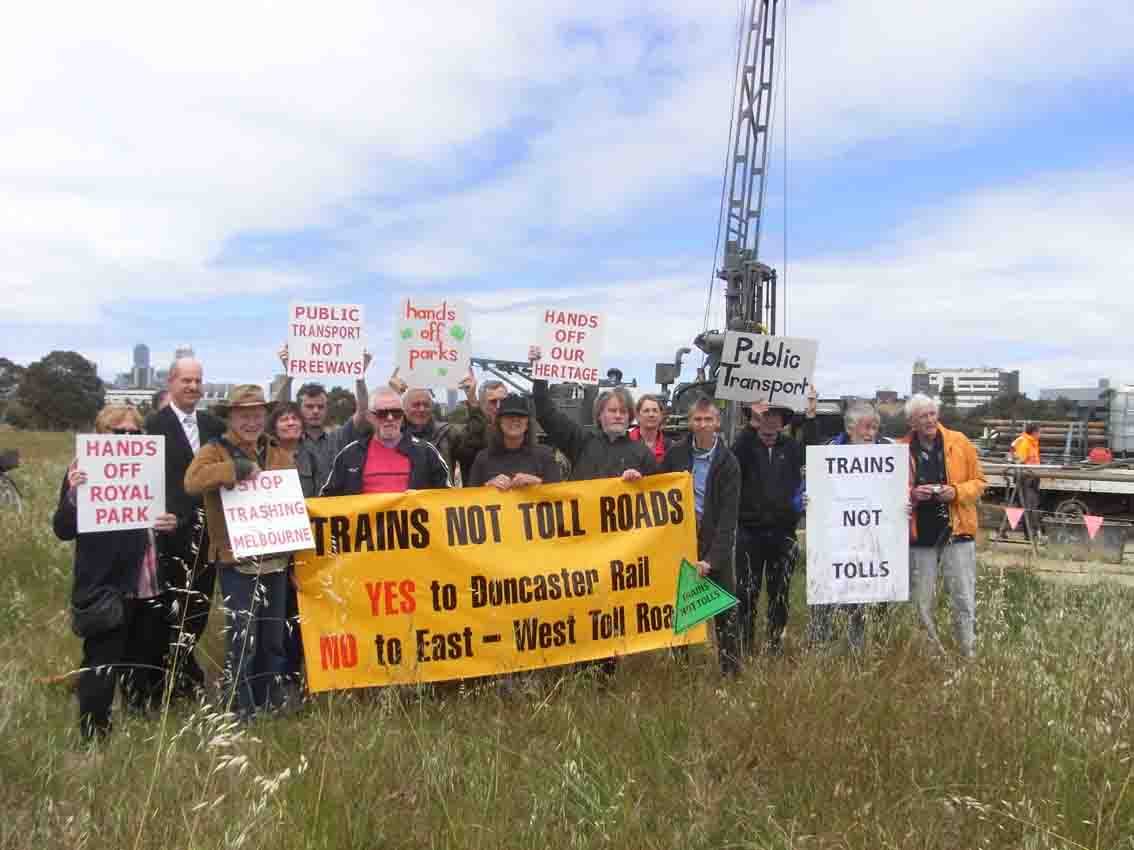

Protesters gathered in Royal Park today at the drill site for a proposed road link which would cut through the park.

Protesters gathered in Royal Park today at the drill site for a proposed road link which would cut through the park.

On every available indicator and every batch of statistics the gap between the powerless and the powerful has grown in Australia. Despite the wealth being generated by a once in a lifetime mining boom, 22 million people living on a continent still have trouble tackling issues that should have been sorted out decades ago. The lid has been kept on dissent through the availability of relatively easy credit for people with investments and jobs.

On every available indicator and every batch of statistics the gap between the powerless and the powerful has grown in Australia. Despite the wealth being generated by a once in a lifetime mining boom, 22 million people living on a continent still have trouble tackling issues that should have been sorted out decades ago. The lid has been kept on dissent through the availability of relatively easy credit for people with investments and jobs.

Hays Paddock, created in 1980, is an open woodland park with wetlands forming part of the Yarra River wildlife corridor. An iconic feature is the children’s discovery playground catering for disabled kids, attracting visitors from all over the metropolitan area. Sports players form only a small percentage of users. The community is alarmed that alcohol will be sold and drinking allowed until late at night on the pavilion verandas. The excuse is to fund the Cricket Club activities, but Hays Paddock is not a business precinct and recent photographs of nude and partially clothed male cricketers there suggest that the Club is not fit to have a liquor licence anywayHearing is scheduled for 9:30 am tomorrow Monday 12 November 2012 at the VCGLR Office, 49 Elizabeth Street Richmond. Melways Map Reference 2 G H2

Hays Paddock, created in 1980, is an open woodland park with wetlands forming part of the Yarra River wildlife corridor. An iconic feature is the children’s discovery playground catering for disabled kids, attracting visitors from all over the metropolitan area. Sports players form only a small percentage of users. The community is alarmed that alcohol will be sold and drinking allowed until late at night on the pavilion verandas. The excuse is to fund the Cricket Club activities, but Hays Paddock is not a business precinct and recent photographs of nude and partially clothed male cricketers there suggest that the Club is not fit to have a liquor licence anywayHearing is scheduled for 9:30 am tomorrow Monday 12 November 2012 at the VCGLR Office, 49 Elizabeth Street Richmond. Melways Map Reference 2 G H2

The Australian Nursing Federation (Victorian Branch) called on Health Minister David Davis to urgently direct public hospitals to increase their intake of recently graduated nurses from Australian universities after it was revealed 805 nursing and midwifery graduates have missed out on a graduate year place next year. Up to 40% of local graduate nurses and midwives are excluded from employment in our hospitals.Shamefully, hospitals are importing foreign nurses and denying locally born and trained nurses an entry year as graduates (often referred to as an intern year).

The Australian Nursing Federation (Victorian Branch) called on Health Minister David Davis to urgently direct public hospitals to increase their intake of recently graduated nurses from Australian universities after it was revealed 805 nursing and midwifery graduates have missed out on a graduate year place next year. Up to 40% of local graduate nurses and midwives are excluded from employment in our hospitals.Shamefully, hospitals are importing foreign nurses and denying locally born and trained nurses an entry year as graduates (often referred to as an intern year).

On November 6, 2012 it was reported that the Victorian government was cooling on the idea of another port for Hastings and instead its planners were casting their collective beady eye in the direction of Werribee. ("

On November 6, 2012 it was reported that the Victorian government was cooling on the idea of another port for Hastings and instead its planners were casting their collective beady eye in the direction of Werribee. ("

The Western Sydney Conservation Alliance is dismayed to hear that the government is talking about withdrawing funding from the Environment Defenders Office (EDO). They say that members of the public struggle to understand the legalities of complex planning proposals and rely on legal advice from the EDO. Members of the NSW Environment Group have been fighting undemocratic development and overpopulation for years in the presence of more and more extreme growthist right-wing governments in NSW. They were recently outraged to hear that the Government Energy Minister had reportedly accused them of consorting with radical socialists and having an agenda to destroy the economy. Their leader, Geoff Brown, has written a letter to Premier Barry O'Farrell and has issued a press release.

The Western Sydney Conservation Alliance is dismayed to hear that the government is talking about withdrawing funding from the Environment Defenders Office (EDO). They say that members of the public struggle to understand the legalities of complex planning proposals and rely on legal advice from the EDO. Members of the NSW Environment Group have been fighting undemocratic development and overpopulation for years in the presence of more and more extreme growthist right-wing governments in NSW. They were recently outraged to hear that the Government Energy Minister had reportedly accused them of consorting with radical socialists and having an agenda to destroy the economy. Their leader, Geoff Brown, has written a letter to Premier Barry O'Farrell and has issued a press release.

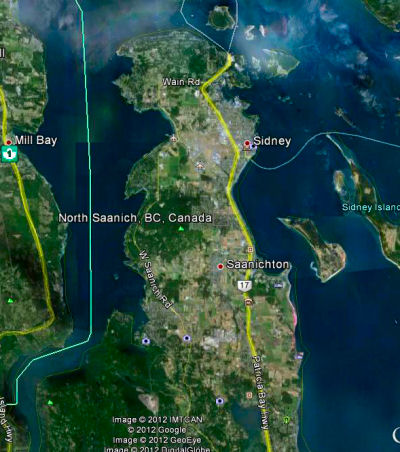

Canada is at the mercy of ruthless growth-merchants, just like Australia. Until recently, however, counter-growthism Canadians seemed to be almost totally unrepresented in their local, provincial and national press. Candobetter Free Press was therefore interested when news came our way of an exchange between growthists and counter-growthists on the British Columbian island of North Saanich. Another counter-growthist writer,

Canada is at the mercy of ruthless growth-merchants, just like Australia. Until recently, however, counter-growthism Canadians seemed to be almost totally unrepresented in their local, provincial and national press. Candobetter Free Press was therefore interested when news came our way of an exchange between growthists and counter-growthists on the British Columbian island of North Saanich. Another counter-growthist writer,

In the US Presidential race, both roads lead to financial collapse, resource depletion, war, irreversible climate change, species extinction, chaos, despair and hopelessness.

In the US Presidential race, both roads lead to financial collapse, resource depletion, war, irreversible climate change, species extinction, chaos, despair and hopelessness.

Researchers have provided evidence of this widespread idea using fairy-wrens to explain how the vibrant blue plumage found on the breeding male of several species could be linked to higher visual sensitivity to ultraviolet.

Researchers have provided evidence of this widespread idea using fairy-wrens to explain how the vibrant blue plumage found on the breeding male of several species could be linked to higher visual sensitivity to ultraviolet.  Two thousand “Temporary” Foreign Workers ---Chinese miners---are coming to extract coal from northeastern British Columbia, Canada, close to three First Nations reserves who suffer unemployment rates over 70% !

Two thousand “Temporary” Foreign Workers ---Chinese miners---are coming to extract coal from northeastern British Columbia, Canada, close to three First Nations reserves who suffer unemployment rates over 70% !

Vancouver’s young generation embraces higher density: “Micro suites” planned for Vancouver-area development.

Vancouver’s young generation embraces higher density: “Micro suites” planned for Vancouver-area development.

Dr Graeme Pearman's speech on "Climate Change Issues" is now available.

Dr Graeme Pearman's speech on "Climate Change Issues" is now available.

Recent comments