The major flaw in the Discussion Paper is that it conceptualises carbon reduction strategies as a silo under principle 5 'Environmental resilience', instead of embedding carbon reduction as a strategy within each of the nine principles.

The Discussion Paper's Principle 5, 'Environmental resilience' is sub optimal as regards international best practice planning to mitigate the predicted effects of climate change and helping to reduce carbon emissions. The Minister's Advisory Committee appears to lack appropriate insights into international best practice in planning regarding climate change mitigation in the structure of cities and planning of new suburbs. For example Vancouver, Canada has a 'Greenest City 2020 Action Plan' divided into ten sub plans, each with long-term goals and specific targets [1] . There is no emphasis in the Discussion Paper on the strategic importance of addressing climate change through planning and this is a major weakness of the Discussion Paper.

Melbourne as a destination will be superseded by the initiatives of countries that are taking active measures to implement an integrated plan with set targets relating to environmental resilience, ecosystems, carbon reduction and waste.

Climate change impacts include: (a) extreme heat waves and hot days; (b) heavy rain; (c) drought; (d) increase in incidence of wildfires; (e) sea level rise and coastal flooding; (f) tropical cyclones and storms.[2] Extreme weather events that were considered a one-in-one-hundred year event are now recurring more frequently in parts of Australia. Associated with these impacts are projections regarding: (i) food security and potential food shortages through impacts on crop yields, distribution, diseases; (ii) health impacts; (iii) cost of living increases; (iv) issues regarding security and social stability.

The Discussion Paper needs to address carbon reduction and environmental resilience strategies as essential components of a new planning strategy for Victoria to ensure its relevance for the next 40 years.

In its 2011 report, the Productivity Commission concluded in relation to the retail sector, that “it appears likely that the size of the gap between Australia and the US has been increasing; nor has Australia made any significant gains in its position in regards to other leading countries” (2011: 67).[3]

These deficits in the structure of the economy are significant contributors to decline in competitiveness and productivity and unless addressed, lead to ongoing economic decline.

The response of yet more population growth exacerbates the decline because it does not create the necessary economic productivity and innovation boost required to increase tax revenues per head of population.

This economic nexus today drives and informs planning, which is now an economic tool rather than a distinguishable discipline in its own right concerned with town planning. The subordination of planning to economic ends is supported by provisions in the Planning and Environment Act 1987 to take into account economic and social considerations when making planning decisions - see extract below. As such, planning has a responsibility to take account of the economic effects on the State.

Em>Extract from PEAct 1987

4. Objectives

"2(d) to ensure that the effects on the environment are considered and provide for explicit consideration of social and economic effects when decisions are made about the use and development of land; "

Furthermore, the availability of land for construction is essential for the ongoing contribution by the construction sector to supporting the State's economy and jobs. It comes at a high environmental cost owing to the construction cycle of project commencements and completions. Furthermore, while contributing to environmental decline this sector has been declining in productivity in relation to the USA construction sector since the 1990s. Daley and Walsh (2011) have argued that labour productivity in the Australian construction sector declined by half relative to its US counterpart between 1990 and 2005. [4]

The importance of productivity competitiveness to economic success and revitalisation is recognised by business leaders and leading academics. In a recent article in The Conversation[7] Professor John Freebairn draws attention to productivity issues facing the Victorian economy, including productivity stagnation and the need respond to demand for new technology and work practices. A shift in focus from less productive industry sectors to those that are more productive is advocated:

"A major challenge facing the Australian economy — particularly the Victorian economy — has been the stagnation of productivity growth this century. The increase in the terms of trade to record high levels over the last decade largely drove higher living standards over this period rather than productivity growth, but this is likely to be eroded in the coming years.

Restarting productivity growth is vital if Victorians' increasing expectations of higher income are to be realised. There is a major challenge for the government, businesses and individuals to better respond to changing markets and buyer needs, to adopt new technology, to change management and work practices, and to allow the transfer of resources and industries from less productive to more productive uses".

1.1.4.4 Structural constraints to the economy

The case presented in the Discussion Paper on Principle 2 does not address the structural constraints in the economy impacting on productivity and therefore on Victoria's competitiveness.

A number of the State's major employment sectors of: (a) retail trade, (b) health care and social assistance, (c) manufacturing, (d) construction and (e) education and training, are sectors that may have either reached their peak or be in decline in terms of their capacity to attract the best and brightest employment candidates. For example, the retail trade with its low productivity status, combined with low research and development output, is a major employment sector in Victoria that does not appear to be addressing competitiveness and therefore may not be positioned to support the aim of contributing to global competition.

1.1.4.5 Recommendations

1. That the structural weaknesses of the Victorian economy as outlined above relating to its major sectors and to productivity be addressed by preparing plans and targets to restructure the economy and to attract people with appropriate qualifications and expertise to help business and industry to transform;

2. That infrastructure replenishment be prioritised in relation to rail transport rather than buses.

1.1.5 Contemporary planning deficits

There is concern that contemporary planning lacks capacity to establish strategies that meet the community's long term needs and each strategy is superseded within a few years. This current strategy will be the sixth strategic plan for Melbourne in 25 years; a plan on average about every four years, together with a number of minor plans.

Major elements of strategies return disappointing outcomes. For example according to the Melbourne 2030 planning strategy, the Docklands development, constructed in the 2000s, would be 'a key location for high-order commercial development and retail and entertainment core of the metropolitan area' (Melbourne 2030, p 37). It was intended as the 'preferred location for uses serving the State or nation' (Melbourne 2030, p 37).

1.1.5.1 Docklands examplar of suboptimal planning performance

Although it benefits from its proximity to water, Docklands offers residents, workers and casual users a vast amount of concrete, shadows and wind tunnels. Public open space is provided mainly in the form of concrete walkways and there is little relief from concrete both in its horizontal and vertical elements.

While it has attracted major corporate and business investment, as an entertainment and retail destination Docklands has failed, despite major advertising campaigns. It is now acknowledged that it needs to be reworked to augment its appeal on these core components of the strategy. Such duplication of effort has significant implications for productivity and acts as a poor exemplar for future major projects.

The suboptimal performance of these major planning investments needs to be assimilated by the government and the planning community and the reasons for poor outcomes need to be clearly identified and published so that mistakes are not repeated. This is essential as it has implications for new planning proposals for revitalisation and renewal such as the Fisherman's Bend rezoning to create new residential suburbs.

2. WHAT DO YOU THINK IS NEEDED TO ACHIEVE THESE OUTCOME PRINCIPLES?

The outcome principles (or generic themes) are better assessed in relation to stated performance targets and outcomes. The Discussion Paper does not have the necessary content and structure to facilitate such feedback. However feedback is provided on each Principle under the discussion and associated recommendations outlined above and below.

3. WHAT ARE THE KEY INGREDIENTS FOR SUCCESS IN ACHIEVING THE VISION OF AN EXPANDED CENTRAL CITY?

3.1 Population growth as a measure of economic growth - a falacy?

Based on the discussion above under paragraph 1.1.3 concerning the structure of the Victorian economy, it appears that population growth masks and exacerbates underlying structural deficits and has potential to reduce per capita revenue. The issues of productivity improvements, innovation and research and development are not addressed through population growth as the cornerstone of the strategy. It is noted that attention is given to innovation clusters but they are conceptionalised as stand alone facilities rather than as a vital component of each sector to strengthen the State's economy and its competitiveness.

3.2 Principle 1: A distinctive Melbourne

The current liveability of Melbourne is informed by the vision of early government planners, surveyors and Lieutenant-Governor Charles La Trobe (large public reserves). Their long term legacies include:

• the city framework of major streets eg Collins St, supported by subsidiary streets linked to them eg Little Collins St, and the associated interconnecting network of arcades and laneways to provide a coherent circulation system, particularly congenial for pedestrians;

• reserving large areas as public parks including: the Treasury Gardens, Carlton Gardens, Flagstaff Gardens, Royal Park and the Royal Botanic Gardens.

3.2.1 Urban structure and place

Urban structure and place would benefit from the following elements:

(a) designed in relation to ecologically sustainable design principles including: (i) zero carbon, (ii) zero waste, (iii) sustainable materials, (iv) local and sustainable food, (v) sustainable transport, (vi) land use and wildlife, (vii) local economy, (viii) sustainable building design principles, site design and technologies;

(b) creating a sense of place through including public piazza's or public squares that have access to lunch time sunshine. These public spaces could also serve to promote the history of the area through the use of plaques and photos. Historic references help create a sense of place and its importance and are a common feature throughout European cities and towns.

3.3 Principle 2: A globally connected and competitive Melbourne

The Discussion Paper's identification of building opportunities in the knowledge economy is strongly supported to improve productivity and to create export opportunities. However the discussion in the paper about the knowledge economy is limited in scope and does not appear to advance the importance of facilitating collaboration between universities, business, industry and government in advancing the knowledge economy through invention and innovation opportunities. Competition from rapidly developing Asian states present potential limitations to competing globally in specific market sectors, for example in manufacturing, unless embedded cost structures are overcome through technological advances.

The global connectivity envisaged in the Discussion Paper needs to put in place a plan to address the State's productivity output and to review the major employment sectors and their capacity to contribute to this principle. A review of this kind needs to prioritise sectors with capacity to contribute, including modelling of their growth trajectory over the strategy timeline.

In terms of freight and logistics it is a major concern that Victoria is over committed to road transport and has no intention to transition to rail, a highly efficient, fast and cleaner form of transport. Increasing energy costs may impact on Victoria's competitiveness through its over reliance on road transport.

3.3.1 Recommendations

1. That the Government set targets for increasing productivity in existing sectors to improve global competitiveness;

2. That opportunities in renewable technologies be included in the work of innovation clusters.

3.4 Principle 3: Social and economic participation

The extensive spread of Melbourne in all directions is a major concern and a failure of planning by successive governments. As discussed above, the role of the construction sector in the State's economy is directly related to repeated extensions to the urban growth boundary. Until the government diversifies the economy and becomes less reliant on this sector, the pattern is likely to continue.

3.5 Principle 4: Strong communities

Affordable housing

The Discussion Paper rightly draws attention to the need to lower pressure on price. It identifies the costs of commercial construction in Melbourne as being higher than other cities and that this limits the ability to build medium density apartments in suitable suburban locations.

Apart from construction costs, another direct impact on affordability is the significant amount of overseas investment in housing, including apartments. Overseas investment places pressure on demand and its role in creating pressure on affordability needs to be investigated and addressed.

Various strategies are applied by European countries to limit impact on housing affordability through overseas investment and it would not be unreasonable for Australia to review the impact on affordability from foreign investment.

As noted in the Discussion Paper the size and standard of houses needs to be considered. Australian house sizes are the largest in the world and this is clearly unsustainable from both a materials and carbon emissions perspective. The economic model involved in construction needs to be reviewed and productivity needs to be increased.

3.6 Principle 5: Environmental Resilience

3.6.1 Energy efficient urban design

Major omissions from the Discussion Paper concerning the outcomes sought are clear targets regarding carbon reduction strategies. The current Australian Building Code for Victoria has low environmental and energy efficiency performance standards for the class of building comprising residential multi storey built form and for commercial buildings, while for houses the plan to increase to 6 star energy efficiency was not implemented and remains at 5 star.

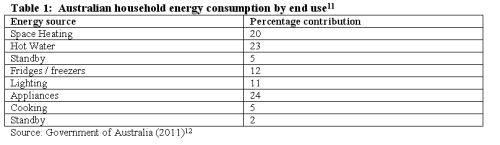

Typically, Australian dwellings account for higher emissions than in the UK, at around 8 tonnes of CO2 per annum, because of the high proportion of coal used in electricity generation. [8] Across Australia residential electricity consumption accounted for 24% of greenhouse gas emissions in 2009.[9] Total residential sector energy consumption across

Australia was 401 petajoules (PJ) in 2008, forecast to rise to 467 PJ in 2020 (DEWHA, 2008). [10]

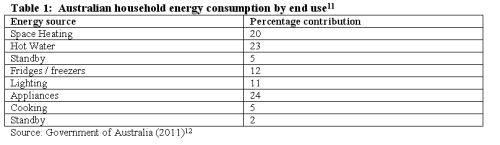

The following table demonstrates the profile across Australia for energy demand within the home. It should be noted that regionally, the share of heating/ cooling load can vary as result of different climate conditions.

[11]

[11]

Source: Government of Australia (2011) [12]

As noted under Principle 4: 'Strong communities' above, new Australian dwellings are a third larger than 20 years ago and are the largest in the world in median floor area at 214.6 square meters in 2009 (ABS). [13]

It is considered essential that the plan for Melbourne's future contains energy efficiency targets for housing to comply with national targets for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2020.

3.6.1.1 Recommendations

1. That effective environmentally sustainable design principles (ESD) including significant energy reduction demand be implemented in new housing communities, including growth corridors and new suburb developments such as Fisherman's Bend;

2. That housing communities based on the UK Bioregional solutions for sustainability such as BedZED be implemented. The Fishermans Bend residential rezoning would be an ideal site at which to implement these standards;

3. That waste reduction combined with recycling be embedded in the infrastructure provided in new housing estates;

4. That with regard to lower impact transport, bicycle paths, separate from roads, be constructed in new housing estates.

3.6.2 Food production

Attention to local food production as a means of advancing food security is strongly supported. This section of the Discussion Paper needs to be advanced with specific plans and targets across the metropolitan area so that all suburbs have access to back up food supplies that are not reliant on transport. The term "Food Security" needs to be addressed as a relevant strategy in the 40 year time line of the Paper.

3.6.2.1 Recommendations

That the food production section of the Discussion Paper needs to be renamed 'Food Security' and advanced with specific plans and targets across the metropolitan area so that all suburbs have access to back up food supplies that are not reliant on transport.

4. WHAT DO YOU THINK OF THE IDEA OF IDENTIFYING AND REINFORCING EMPLOYMENT AND INNOVATION CLUSTERS ACROSS MELBOURNE?

4.1 Innovation clusters

It is not clear what is intended by this proposal as the present innovation clusters involve universities and their location and numbers are not likely to be flexible. Universities are mandated to conduct research and the outcomes of research include invention and innovation. All businesses ought to carry out innovation and a useful model for this is to seek consultancy engagement with nearby universities on specific aspects of their business. For example, the City of Whitehorse has engaged academic consultancy to assist it to develop and implement a 'Climate change adaptation plan' in 2010 and an associated set of environmental strategies.

While innovation clusters are a good model for reinforcing employment, it may not be feasible to extend the clusters associated with The University of Melbourne and Monash Universities to all Victorian universities owing to cost and expertise limitations. An alternative model is to facilitate consultancy engagement with academic staff with appropriate expertise to assist business and government to develop their plans based on international best practice research and competitiveness.

4.1.1 Recommendation

That business innovation, competitiveness and growth be augmented through facilitating engagement / consultancies with academic staff working as part of a team in business and government to develop their plans based on international best practice research and competitiveness.

5. WHAT IS NEEDED TO SUPPORT GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT IN REGIONAL CITIES?

5.1 Principle 6: A polycentric city linked to regional cities

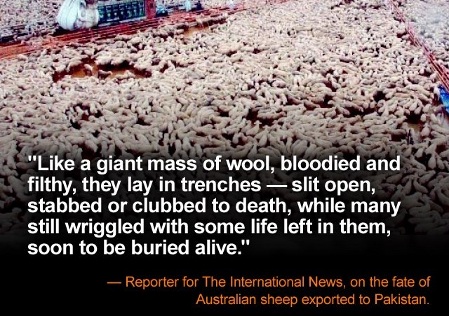

The environmental and ecological implications of city and regional linkages throughout the State need to be considered. Victoria has the lowest proportion of its original extent of native vegetation remaining of any Australian state or territory. Across much of Victoria the extent, condition and configuration of remnant native vegetation is the primary determinant of ecological health.

Fragmented landscapes make up nearly 79% of Victoria and account for 54% of the current extent of native vegetation. Fragmentation is a driver of ecosystem fragility and consideration needs to be given to reinforcing green wedges and corridors and ensuring that they are not impacted by infrastructure and development. The condition of each bioregion in Victoria have been mapped and identified and this information can be used in determining sites for city - regional linkages.

Ongoing development of the urban growth boundary is likely under the proposals in the Discussion Paper and there is concern that the vision of a city of cities and regional linkages is a strategy to exploit land indiscriminately for development without setting aside land for agricultural and environmental/ecological purposes.

This is a particularly heavy handed vision that is ultimately self-defeating as the environmental costs are eventually a matter to be addressed by the State. Issues of pollution, congestion, ecosystem breakdown, species extinction, threats and vulnerabilities are likely scenarios under the model being advanced in the Discussion Paper.

5.1.1 Recommendations

1. That no further expansion of the urban growth boundary be permitted;

2. That productive agricultural land be identified and quarantined from development;

3. That agricultural land in the metropolitan area be identified and set aside for this purpose;

4. That documented fragmentation of ecosystems be addressed through funds set aside for restoration;

5. That the framework for regional linkages be based on consideration of the protection of environmental and ecological systems, taking into account the mapping and identification of each bioregion and its condition.

6. WHAT DO YOU THINK OF THE IDEA OF A ‘20 MINUTE CITY’?

6.1 Principle 7: Living Locally - A '20 minute city': linked to 'Unlocking capacity in established suburbs'

The 20 minute city sounds appealing on face value but it has a number of inherent corollaries that are not adequately outlined in the paper. These include:

(a) the assumption that population growth contributes to the economy but without providing documented evidence;

(b) an extensive duplication of facilities and infrastructure implied in this strategy can only be justified economically on the grounds of a minimum quantum of consumers and is therefore based on high populations and building densities;

(c) in areas where the population is ageing it is likely that the population density would need to be higher than otherwise to justify investment as this demographic are lower consumers;

(d) the issue regarding affordability as presented in the Discussion Paper means reducing the price of a three bedroom townhouse apartment by $100,000. What is not disclosed is that developers base their business model on gaining specific returns on investment in any project and this needs to be achieved for the development to proceed. The reduction of $100,000 on the price of an individual townhouse at a development site needs to be made up through more townhouses being built on the site and therefore contributing to higher density.

(e) the 20 minute city is another way of referring to an "activity centre" as defined under Melbourne 2030 but with the disadvantage that high density development and population will be allowed to occur throughout suburban streets and not limited to activity centres.

The '20 minute city' is associated with the 'Unlocking capacity in established suburbs' proposal and together they would involve a radical and undesirable departure from the current planning scheme. As noted above under paragraph 5.2, these proposals devolve planning decisions direct to developers and effectively remove local government from substantive planning decisions. A characteristic of this system is radical free market development together with uncertainty as to the type of developments that would take place in any residential street.

6.1.1 Recommendation

That the '20 minute cit'y proposal be reviewed taking into account the issues outlined above.

7. HOW CAN ESTABLISHED SUBURBS ACCOMMODATE THE NEEDS OF CHANGING POPULATIONS AND MAINTAIN WHAT PEOPLE VALUE ABOUT THEIR AREA?

7.1 Unlocking capacity in established suburbs - code for high density and high rise and radical free market development

'Unlocking capacity in established suburbs' is code for: (a) high population density and high rise development in existing suburbs and suburban streets; (b) placing pressure on existing infrastructure to cope with higher population demands but without expenditure on system renewal and replenishment; (c) further vegetation clearance and ecological impacts; (d) decline in living standards.

As a planning strategy for the next 40 years in Victoria this proposal is one of the most objectionable aspects of the Discussion Paper as it would:

(a) ensure public uncertainty throughout the metropolitan region regarding development levels in individual streets and

(b) devolve planning decisions direct to developers and effectively remove local government from substantive planning decisions.

Established suburbs of high value per square metre and access to infrastructure would be especially vulnerable to high density development. This includes municipalities such as Boroondara, Stonnington, Bayside, Port Phillip and Banyule.

The implications of such a strategy need to be considered in terms of political ramification,s as individuals who invest in these suburbs have a high commitment to their amenity. The convergence of threats to:

(a) the belief that planning is orderly and determined by local government; and

(b) local neighbourhood amenity and character,

are highly contentious and provocative.

7.1.1 Recommendation

That the proposal to unlock capacity in established suburbs be withdrawn.

8. HOW DO WE ENSURE A HEALTHY AND SUSTAINABLE ENVIRONMENT FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS?

8.1 Planning for public open space

As noted under paragraph 3.1, the establishment of major areas of reserves for parks was an essential feature of the layout of early Melbourne. Despite substantial population growth, State and local governments have not supplemented the total area of parkland in relation to population growth. Consequently parks today are under pressure to act as multi purpose facilities, especially for use by sporting groups; in some cases, such as Royal Park, sections of them have been redeployed for public buildings.

The legislative framework supporting public open space, such as provision in the Sub Division Act and in the Planning and Environment Act, is very poor, with the result that minimal increases have occurred over decades.

Historically, it should be noted that Victoria had an open space per capita standard which was originally developed by the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works in 1954.[14] An open space per capita standard used in Victoria is 3.03 hectares per thousand people, of which 1.5 hectares is for organised recreation.

The importance of this standard is that it sets a baseline of public open space in relation to population. The standard needs to be further developed by taking into account population density by precinct, together with the specific needs of each community.

8.1.1 Recommendations

1. That urban structure be designed in relation to ecologically sustainable design principles including: (i) zero carbon, (ii) zero waste, (iii) sustainable materials, (iv) local and sustainable food, (v) sustainable transport, (vi) land use and wildlife, (vii) local economy, (viii) sustainable building design principles, site design and technologies;

2. That a sense of place be created through public piazza's or public squares with access to lunch time sunshine;

3. That provision for public open space be addressed by relating the amount of public open space to population by precinct and municipality;

4. That the Sub Division Act be changed to mandate contributions to Local Government specifically for the purchase of additional land for this purpose rather than allowing contributions to be spent on maintenance of existing open space.

8.2 Public transport infrastructure

It should be noted that early governments, developers and business investors were responsible for establishing an extensive public transport infrastructure through the development of tram and rail networks and systems. The first railway line was established in the 1850s when Melbourne's population was around 20,000 people. The first tram lines were opened in the 1880s when the population of Melbourne was still under 500,000.

Today's tram and rail networks have added limited capacity to the public transport infrastructure in place by the 1920s and investment has not kept pace with population growth and demand. It is significant that there are no fast trains in Melbourne and that the network provides limited service to the growth corridor suburbs and no service to Melbourne Airport, Tullamarine. It is essential for a globally connected city to offer favourable international comparisons and an airport - city train link is well overdue.

There is a strong need for the Federal government to provide funding for states to supplement their aged public transport infrastructure to bring it up to date with internationally benchmarked comparisons including fast rail. Much of the surplus of the previous Liberal Federal government was returned to individuals in the form of tax cuts instead of being put towards public infrastructure replenishment. Policies that ignore national needs create capacity constraints that impact nationally in the longer term. It is considered that the State government needs to argue this case at COAG and to establish the principle at COAG that accumulated surpluses are to be used for national infrastructure upgrades and replenishment and not distributed to individuals as tax cuts.

8.2.1 Recommendations

1. That the State government presents a case at COAG to establish the principle that accumulated budget surpluses are to be used for national infrastructure upgrades and replenishment and not distributed to individuals as tax cuts;

2. That a dual train line from Melbourne to Melbourne Airport, Tullamarine be budgeted and implemented as a high priority.

8.3 Energy efficient urban design

As noted under paragraph 3.6.1, clear targets are required regarding carbon reduction strategies. Electricity consumption accounted for 24% of greenhouse gas emissions in 2009 and this outcome needs to be reduced.

8.3.1 Recommendations

The recommended reduction strategies are: (a) reduction of house sizes by 33% to bring them back in line with the early 1990s and proportional to smaller family sizes; (b) mandated environmentally sustainable design standards including passive solar and other low cost design measures; (c) introduce gradual targets aimed at zero carbon emissions and waste by 2020.

9. WHAT DO YOU THINK ABOUT THE POSSIBLE WAYS OF FUNDING INFRASTRUCTURE?

9.1 Federal government contributions to infrastructure

As noted under paragraph 8.2 there is a strong need for the Federal government to provide funding for states to supplement their aged public transport infrastructure to bring it up to date with internationally benchmarked comparisons including fast rail.

The distribution of previous accumulated Federal budget surpluses to individuals in the form of tax cuts is considered inappropriate. Instead, surpluses should be put towards public infrastructure replenishment. The State government needs to argue this case at COAG and to establish the principle at COAG that accumulated surpluses are to be used for national infrastructure upgrades and replenishment and not distributed to individuals as tax cuts.

10. HOW CAN ALL LEVELS OF GOVERNMENT, BUSINESS AND COMMUNITY WORK

TOGETHER TO CREATE THE CITY YOU WANT?

10.1 Principle 9 Leadership and partnership

Concern is expressed over principle 9 regarding the suggestions of: (1) a new governance structure and (2) a revised planning policy. No details are provided and these proposals are advanced at the back of the Discussion Paper.

10.1.1 Recommendations

1. That clarification be provided about the proposal to introduce: (1) a new governance structure and (2) a revised planning policy.

2. That any changes to introduce a free market for development and remove local government from responsibility for all planning decisions are rejected.

11. ANY OTHER COMMENTS

11.1 Comments on the capacity of the Discussion Paper "Melbourne, let's talk about the future" to effectively support strategic planning

Overall, the principles and ideas advanced in the Discussion Paper, "Melbourne, let's talk about the future" are elusive, vaporous and aspirational as the document contains no clear direction as to what it intends to achieve. The absence of intent makes it difficult to contemplate the vision and strategy being advanced. On this count alone, the document fails as there is no tangible framework being advanced on which one can comment.

The Discussion Paper has been prepared to seek feedback from the community for the preparation of a new planning strategy for Melbourne but as a planning strategy for the next 40 years it fails on several counts:

1. climate change and its diverse impacts are potentially the major influence over the economy, liveability, business productivity and competition but its relevance over the 40 year timeline of the strategy appears to be afforded relatively minor status rather than addressing it as a core component of the strategy;

2. capturing business opportunities arising from innovation and invention in developing resilience against climate change impacts appear to be lacking despite ideas for innovation clusters and a metropolitan framework based on jobs outlined in Principle 2;

3. the relevant legislative framework supporting planning such as the Planning and Environment Act and the Sub Division Act contain weak infrastructure provisions but the document is unclear as to how best to respond to the identified urgent need for infrastructure upgrades;

4. the document appears to be primarily concerned with addressing: (a) questions of economic importance to Victoria such as attracting business investment and facilitating business investment through freight, ports, airport upgrades and additions; (b) optimising existing soft and hard infrastructure by maximising populations within existing suburbs, euphemistically called 'the 20 minute city' and unlocking capacity in established suburbs; (c) job creation; and (d) social questions such as housing affordability and as such appears to be essentially an economic plan;

5. the concept of town planning is subordinated to delivering additional construction opportunities through: (a) density intensification and (b) continuing urban sprawl through linkages with regional cities;

6. an acceptance of road transport as the major means of commuting and for freight instead of directing a transition to rail which is far better developed in the international cities with which connection is anticipated;

7. no tangible plan and enabling mechanisms for delivering additional public open space in the form of parks and gardens to alleviate congestion and to compensate for high density livings;

8. the Discussion Paper is framed around a series of principles and ideas but there is no clear identification of the core strategies that will enable Melbourne to be positioned for the future and to successfully achieve its economic, social and environmental aspirations;

9. lack of protection of the green wedges (p40, Principle 5, Environmental Resilience, does not confirm protection but states that it is expected that protection will continue);

10. absence of vision for developing housing communities based on the UK Bioregional solutions for sustainability such as BedZED. The Fishermans Bend residential rezoning would be an ideal site at which to implement sustainable communities based on the One Planet Communities principles. See website at: http://www.bioregional.com/flagship-projects/one-planet-communities/bedzed-uk/

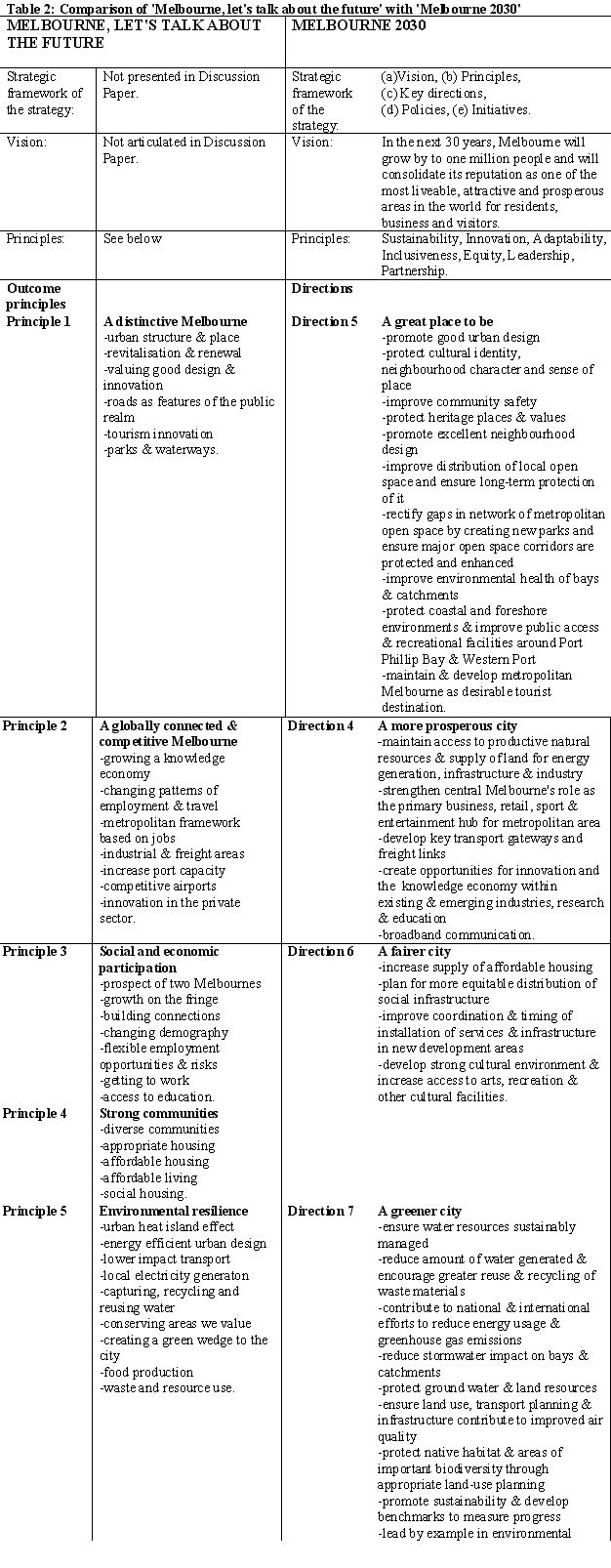

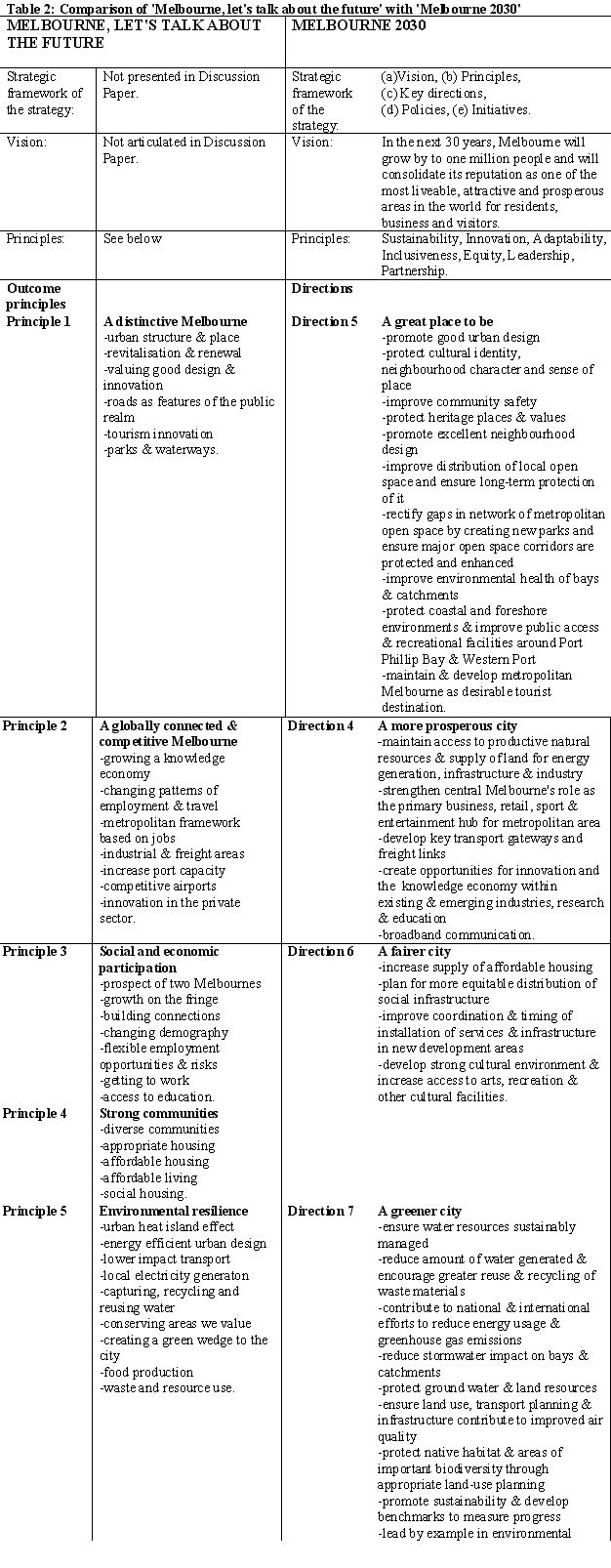

The Melbourne 2030 document, prepared in October 2002, and made available for public comment, as a planning strategy, was a superior plan in that it outlined a fully formed strategic framework including the following elements:

(a) statement of vision

(b) set of principles

(c) a set of 9 key directions for example, Direction 5: 'A great place to be' (Melbourne 2030 p91);

(d) a range of clear policies supporting each key direction, for example, '5.6 'Improve the quality and distribution of local open space and ensure long-term protection of public open space'(Melbourne 2030 p91);

(e) a set of specific initiatives intended to support each separate policy, for example, 5.6.1 'Review mechanisms for strategic open space planning in consultation with open space management agencies in light of the Parks Victoria strategy 'Linking People and Spaces'.

The Discussion Paper, 'Melbourne, let's talk about the future' barely acknowledges that an existing strategy is in place (it may not agree with it but it ought to recognise that Melbourne 2030, with its various difficulties, is the current planning strategy) and in many ways, this draft strategy builds on Melbourne 2030 - see Appendix A, Table 1.

It should be noted that this will be the sixth strategic plan for Melbourne in 25 years; a plan on average about every four years, together with a number of minor plans. It is clearly unsatisfactory and inefficient for the State government to be directing considerable resources into planning strategies at such regular intervals and implies that the plans are superficial and / or uncertain about the proposals advanced.

According to Michael Buxton [15] some earlier plans for Melbourne involved years of research and investigation together with the modelling of options. He considers that the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW) strategic planning was exemplary for investigation and consideration of options, particularly the 1954 and 1971 plans.

The 1954 plan entitled 'Melbourne Metropolitan Planning Scheme Report' observes:

'The plan has involved three years of painstaking and careful study of Melbourne and its people. Almost every phase of city and community life was thoroughly examined and analysed to ascertain Melbourne's present and future needs, and to determine the most suitable course for sound and progressive development." p132 [16]

This level of research and preparation formed a comprehensive, informative and long-term plan.

11.1.1 Recommendations

That the Discussion Paper, "Melbourne, let's talk about the future" be revised as a fully formed strategic framework including the following elements, as contained in the Melbourne 2030 document:

(a) statement of vision

(b) set of principles (possibly adapted from the current Discussion Paper)

(c) a set of key directions for example, Direction 5 in Melbourne 2030: 'A great place to be' (Melbourne 2030 p91);

(d) a range of clear policies supporting each key direction, for example, '5.6 'Improve the quality and distribution of local open space and ensure long-term protection of public open space' (Melbourne 2030 p91);

(e) a set of specific initiatives intended to support each separate policy, for example, 5.6.1 'Review mechanisms for strategic open space planning in consultation with open space management agencies in light of the Parks Victoria strategy 'Linking People and Spaces' (Melbourne 2030 p103).

11.2 Civil defence and town planning

The 1954 MMBW 'Melbourne Metropolitan Planning Scheme Report' includes a chapter entitled 'Decentralisation and Civil Defence'. In a section called "The problem of civil defence" it draws attention to the need for town planning to consider the risks of warfare and to take precautions to minimise loss of life and property in the event of attack. It recognises the role of public open space in breaking up the urban mass of buildings and residences supported by a system of communication to assist with movement throughout the area.

"The increasing concentration of population in cities must be looked at from a new angle. No large city today can afford to ignore the risks of warfare, and must take all practicable precautions in its civic development to minimise loss of life and property should it be attacked". [17]

Although contemporary Western society has become complacent about war, the complete lack of planning for its potential may appear negligent.

11.2.1 Recommendation

It is recommended that consideration be given to including the provision for civil defence in the current metropolitan Melbourne planning strategy as its absence appears to assume that planning for this purpose is irrelevant.

APPENDIX A

COMPARISON OF MELBOURNE, LET'S TALK ABOUT THE FUTURE WITH MELBOURNE 2030

NOTES

[1] See http://vancouver.ca/green-vancouver/targets-and-priority-actions.aspx

[2] The Critical Decade: Extreme Weather. Report by the Australian Climate Commission, April 2013

[3Productivity Commission Economic Structure and Performance of the Australian Retail Industry, Draft Report, Canberra, July 2011

[4] Daley, John and Walsh, Marcus (2011), ‘Losing the productivity race’, Australian Financial Review, 7 July, 63.

[5] Sources: ABS, Australian System of National Accounts (5204.0), State Accounts (5220.0), and The Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Quarterly (6291.0.55.003; Grattan Institute calculations, based on table by Eslake, S. in 'An analysis of Victoria’s labour productivity performance. Presentation to a forum hosted by Victorian Department of Innovation, Industry and Regional Development, 14th April 2010.

[6] Eslake, S. in 'An analysis of Victoria’s labour productivity performance. Presentation to a forum hosted by Victorian Department of Innovation, Industry and Regional Development, 14th April 2010.

[7] Freebairn, J. "Flat economy will continue to challenge the Victorian government" in 'The Conversation', an online academic journal, 13 March 2013.

[8] The contribution of housing to carbon emissions and the potential for reduction: an Australia-UK comparison, 18th Annual Pacific-Rim Real Estate Society Conference Adelaide, Australia, January 2012

[9] Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency. Australian National Greenhouse Accounts, National Inventory by Economic Sector, Commonwealth of Australia, 2009, p6.

[10] Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. Energy use in the Australian Residential Sector, 1990-2020, Commonwealth of Australia, 2008

[11] The contribution of housing to carbon emissions and the potential for reduction: an Australia-UK comparison, 18th Annual Pacific-Rim Real Estate Society Conference Adelaide, Australia, January 2012, p6.

[12] Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency. Quarterly Update of Australia’s National Greenhouse gas Inventory, March Quarter 2011, Commonwealth of Australia, 2011

[13] The contribution of housing to carbon emissions and the potential for reduction: an Australia-UK comparison, 18th Annual Pacific-Rim Real Estate Society Conference Adelaide, Australia, January 2012, p5.

[14] Victorian Environmental Assessment Council Melbourne Metropolitan Investigation Discussion Paper, October 2010, p102.

[15] “Melbourne Metropolitan Strategy – Con Job or for Real?”. Buxton, M, Professor of Environment and Planning, RMIT University.

[16] Melbourne Metropolitan Planning Scheme Report 1954, Explanation of the planning scheme submitted to the Town Planning Committee by E. F. Borrie, M.C., M.C.E., MIC . Aust., F.A.P.I., Chief Planner, on behalf of the planning staff.

[17] MMBW 'Melbourne Metropolitan Planning Scheme Report' 1954, p28

A rally was held today on the steps of Parliament House in Melbourne " to protest against new laws proposed by the Napthine government which are undeniably bad news for forests.

A rally was held today on the steps of Parliament House in Melbourne " to protest against new laws proposed by the Napthine government which are undeniably bad news for forests.

For all you depressed wildlife battlers out there, here is a truly 'good news' koala story about a wildlife warrior hero, James Fitzgerald, who has placed nearly 800ha of what looks like good sub-alpine land in trust for koalas. Even better, the koala population there turns out to have strong new genetic properties and is chlamydia free!

For all you depressed wildlife battlers out there, here is a truly 'good news' koala story about a wildlife warrior hero, James Fitzgerald, who has placed nearly 800ha of what looks like good sub-alpine land in trust for koalas. Even better, the koala population there turns out to have strong new genetic properties and is chlamydia free!

What would Dr Nugget Coombs think of our treatment of the environment and the economy today? Quark applies a retrospectoscope to the problem as she reports on a 1970 Boyer Lecture on environment and economy.

What would Dr Nugget Coombs think of our treatment of the environment and the economy today? Quark applies a retrospectoscope to the problem as she reports on a 1970 Boyer Lecture on environment and economy.

[11]

[11]

Bandicoot writes in

Bandicoot writes in

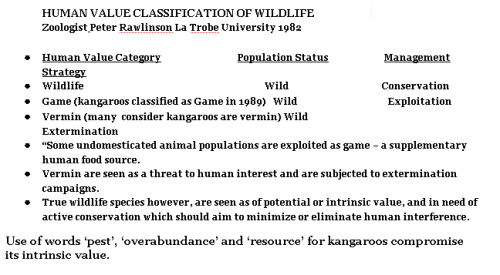

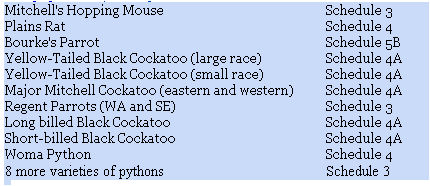

The Australian Wildlife Protection Council (AWPC) is gravely concerned by the ‘use and commercialisation of Australian native animals’, their extinction rates, cruelty inflicted on them, and recreational hunting. Even more so, given that Australia has the world’s highest extinction rate. Instead of apologising for crimes against nature, the Victorian State Government seeks to extend further exploitation.

The Australian Wildlife Protection Council (AWPC) is gravely concerned by the ‘use and commercialisation of Australian native animals’, their extinction rates, cruelty inflicted on them, and recreational hunting. Even more so, given that Australia has the world’s highest extinction rate. Instead of apologising for crimes against nature, the Victorian State Government seeks to extend further exploitation.

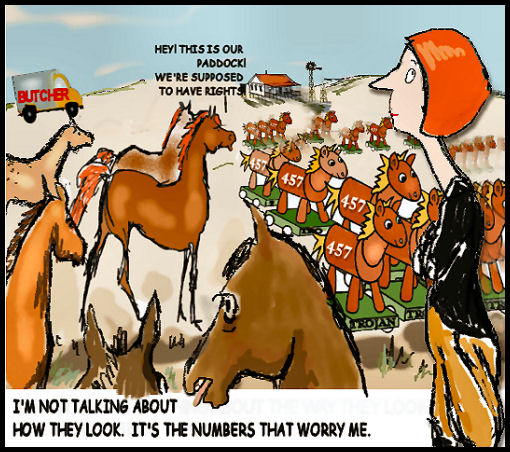

Unbeknown to most of those commenting on the numbers of 457 visas outside the EMA (Enterprise Migration Agreement) issue, as part of Doha round of trade negotiations, the Labor Government processed and negotiated away Australia’s rights to apply labour-market testing to temporary overseas workers in the 457 visa program.

Unbeknown to most of those commenting on the numbers of 457 visas outside the EMA (Enterprise Migration Agreement) issue, as part of Doha round of trade negotiations, the Labor Government processed and negotiated away Australia’s rights to apply labour-market testing to temporary overseas workers in the 457 visa program.

[Candobetter.net Editor 4 April 2018. Our attention has been drawn to the fact that the title of this article could make people think that candobetter.net is generally in agreement with Dr Yugovic on this matter. The fact is that we do not agree, but we have permitted him to put his argument here, in response to other articles that find that tree dieoff has many other causes. These articles can be found under the general topic of

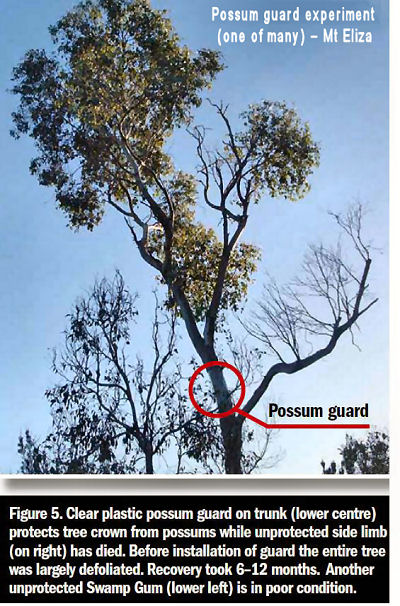

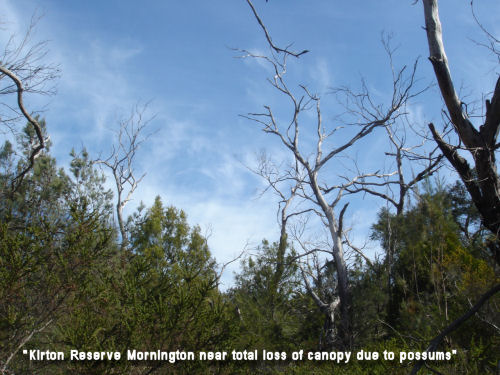

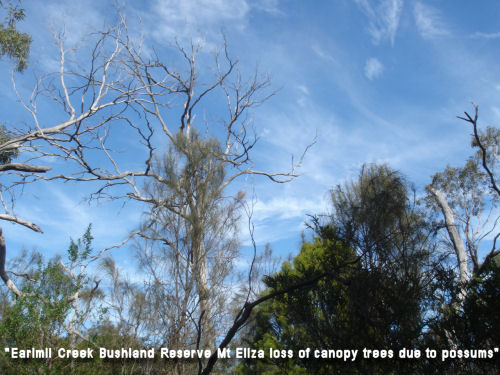

[Candobetter.net Editor 4 April 2018. Our attention has been drawn to the fact that the title of this article could make people think that candobetter.net is generally in agreement with Dr Yugovic on this matter. The fact is that we do not agree, but we have permitted him to put his argument here, in response to other articles that find that tree dieoff has many other causes. These articles can be found under the general topic of  Possum induced tree decline is very real and is a very serious threat to indigenous trees on the Mornington Peninsula, with thousands of trees dead or dying in many locations. Just drive down Old Mornington Road, Walkers Road or Kunyung Road in Mount Eliza or visit Mount Martha Park to see for yourself, but you need to be able to identify indigenous eucalypts as the many planted non-indigenous eucalypts are generally not eaten by possums. I also attach further photographic evidence.

Possum induced tree decline is very real and is a very serious threat to indigenous trees on the Mornington Peninsula, with thousands of trees dead or dying in many locations. Just drive down Old Mornington Road, Walkers Road or Kunyung Road in Mount Eliza or visit Mount Martha Park to see for yourself, but you need to be able to identify indigenous eucalypts as the many planted non-indigenous eucalypts are generally not eaten by possums. I also attach further photographic evidence.

Martin Bryant has been sentenced to prison for the rest of his life because he was convicted of killing 35 people and wounding 23 others at Port Arthur in 1996. According to Vietnam Veteran, the late Brigadier Ted Serong, only the most elite of Australian troops could have performed such a feat of rapid movement and marksmanship, rarely missing, and with such a high proportion of fatal hits.

Martin Bryant has been sentenced to prison for the rest of his life because he was convicted of killing 35 people and wounding 23 others at Port Arthur in 1996. According to Vietnam Veteran, the late Brigadier Ted Serong, only the most elite of Australian troops could have performed such a feat of rapid movement and marksmanship, rarely missing, and with such a high proportion of fatal hits. Martin Bryant, aged 29, had an IQ of 66, equivalent to that of an 11 year old child, which put him in the lowest 1%-2% of the population.

Martin Bryant, aged 29, had an IQ of 66, equivalent to that of an 11 year old child, which put him in the lowest 1%-2% of the population. The Greens are at the crossroads as a political party — should they focus on the wider concerns of the electorate, or should they stick to environmentalism? For instance, the humanitarian crying out for the suffering of refugees needs to be focused on what drives people to become refugees, like our engagement in unjust wars, environmental damage and over-population. Dr Peter Cock says they need to stay green. [Comment from Candobetter.net editor: Some of us here think the Greens need to rebrand if they don't become green, but we appreciate the discussion in this article, which targets our concerns.]

The Greens are at the crossroads as a political party — should they focus on the wider concerns of the electorate, or should they stick to environmentalism? For instance, the humanitarian crying out for the suffering of refugees needs to be focused on what drives people to become refugees, like our engagement in unjust wars, environmental damage and over-population. Dr Peter Cock says they need to stay green. [Comment from Candobetter.net editor: Some of us here think the Greens need to rebrand if they don't become green, but we appreciate the discussion in this article, which targets our concerns.]

A permit has been issued by the Department of Environment and Heritage Protection to cull 2,000 Agile Wallabies at Mission Beach along the North Queensland Coast in an area almost pristine not so long ago. Wildlife activists say that there may only be about 500 wallabies there now but a lot more humans.

A permit has been issued by the Department of Environment and Heritage Protection to cull 2,000 Agile Wallabies at Mission Beach along the North Queensland Coast in an area almost pristine not so long ago. Wildlife activists say that there may only be about 500 wallabies there now but a lot more humans.

Mornington Peninsula[1] The writer of an article about ecosystem need for top predators claims that "Observations on trees and experience with possum guards by the author indicate that possums are the major cause of tree decline on the Mornington Peninsula ..."

Mornington Peninsula[1] The writer of an article about ecosystem need for top predators claims that "Observations on trees and experience with possum guards by the author indicate that possums are the major cause of tree decline on the Mornington Peninsula ..." Hans Brunner: I am somewhat alarmed that a highly respected ecologist, Dr. Jeff Yugovic, can declare that possums on the peninsula are in plague proportions (published in the journal Indigenous,

Hans Brunner: I am somewhat alarmed that a highly respected ecologist, Dr. Jeff Yugovic, can declare that possums on the peninsula are in plague proportions (published in the journal Indigenous,  Today the Australian Financial Review carried a surprising and uncharacteristic number of remarks about the high cost of privatisation and the benefits of public provision of vital services.

Today the Australian Financial Review carried a surprising and uncharacteristic number of remarks about the high cost of privatisation and the benefits of public provision of vital services. Everyone gets a smaller slice of the national cake and pays more for it. The arrival of Australia’s 23 millionth person tomorrow is no cause for celebration, according to Sustainable Population Australia (SPA).

Everyone gets a smaller slice of the national cake and pays more for it. The arrival of Australia’s 23 millionth person tomorrow is no cause for celebration, according to Sustainable Population Australia (SPA).

Today Australia reaches a population of 23 million. If we assess this against the status of our life-support systems, we should be alarmed. Neither Australia nor Earth is ecologically sustainable as shown by our national state of the environment reporting and the estimate that humans are consuming 150% of Earth’s renewable capacity. Population size is one of the underlying drivers of these trends. Should they continue, the implications for future generations are clear.

Today Australia reaches a population of 23 million. If we assess this against the status of our life-support systems, we should be alarmed. Neither Australia nor Earth is ecologically sustainable as shown by our national state of the environment reporting and the estimate that humans are consuming 150% of Earth’s renewable capacity. Population size is one of the underlying drivers of these trends. Should they continue, the implications for future generations are clear. Way back in 1994, The Australian Academy of Science said “In our view, the quality of all aspects of our children’s lives will be maximised if the population of Australia by the mid 21st Century is kept to the low, stable end of the achievable range, i.e. to approximately 23 million” and “If our population reaches the high end of the feasible range (37 million), the quality of life of all Australians will be lowered by the degradation of water, soil, energy and biological resources.”

Way back in 1994, The Australian Academy of Science said “In our view, the quality of all aspects of our children’s lives will be maximised if the population of Australia by the mid 21st Century is kept to the low, stable end of the achievable range, i.e. to approximately 23 million” and “If our population reaches the high end of the feasible range (37 million), the quality of life of all Australians will be lowered by the degradation of water, soil, energy and biological resources.”  What's wrong with the Canadian Environmental Movement? Why don't Canadian environmental organisations protest about the huge impact of successive government's policies to promote mass immigration to Canada? The six million more people imported to Canada since 1991 would account for four times as much GHG emissions as the Alberta tar sands project. Overpopulation is the number one issue that multiplies every other impact. Why is this message of the original promoter of Earth Day forgotten today?

What's wrong with the Canadian Environmental Movement? Why don't Canadian environmental organisations protest about the huge impact of successive government's policies to promote mass immigration to Canada? The six million more people imported to Canada since 1991 would account for four times as much GHG emissions as the Alberta tar sands project. Overpopulation is the number one issue that multiplies every other impact. Why is this message of the original promoter of Earth Day forgotten today?

"The utterly biased and relentless Murdoch press in Melbourne, Sydney and nationally through The Australian has played a big role in destroying Julia Gillard's standing with the electorate, such that Tony Abbott is well placed to win control of both houses in the coming September 14 Federal election."

"The utterly biased and relentless Murdoch press in Melbourne, Sydney and nationally through The Australian has played a big role in destroying Julia Gillard's standing with the electorate, such that Tony Abbott is well placed to win control of both houses in the coming September 14 Federal election." This article is an extract from Stephen Mayne's newsletter, The Mayne Report, Monday, April 22, 2013, 11:13am

This article is an extract from Stephen Mayne's newsletter, The Mayne Report, Monday, April 22, 2013, 11:13am

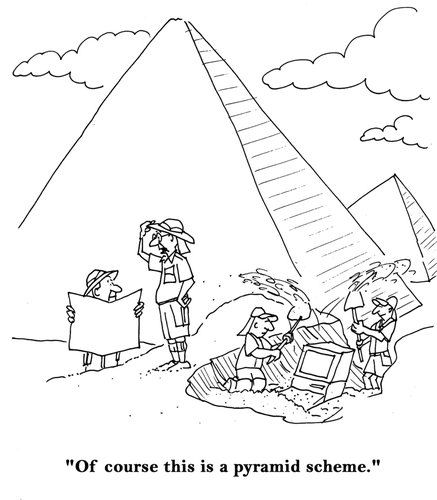

Bill Gross, Nouriel Roubini, Laurence Kotlikoff, Steve Keen, Michel Chossudovsky, the Wall Street Journal and many others say that our entire economy is a Ponzi scheme.

Bill Gross, Nouriel Roubini, Laurence Kotlikoff, Steve Keen, Michel Chossudovsky, the Wall Street Journal and many others say that our entire economy is a Ponzi scheme. Former Reagan budget director David Stockton just agreed:

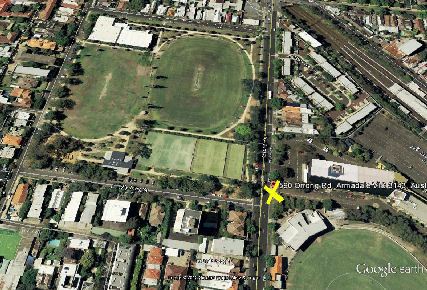

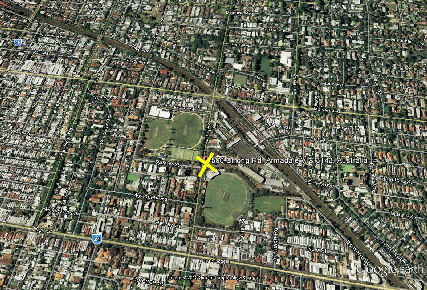

Former Reagan budget director David Stockton just agreed: NOTE! Venue changed to Court 2, Ground Floor, Old High Court, 450 Little Bourke Street. LAST MINUTE REMINDER ABOUT THE SUPREME COURT APPEAL - TUESDAY 16 AND 17 APRIL 2013. This is about your fundamental property and citizenship rights - the very basis of democracy. Come and sit in the gallery.This involves the Orrong Group. The fact that this case has arisen is a consequence of commercially driven population growth in Victoria and Australia. The Supreme Court has changed the venue for the Hearing tomorrow, commencing at 10.30am.

NOTE! Venue changed to Court 2, Ground Floor, Old High Court, 450 Little Bourke Street. LAST MINUTE REMINDER ABOUT THE SUPREME COURT APPEAL - TUESDAY 16 AND 17 APRIL 2013. This is about your fundamental property and citizenship rights - the very basis of democracy. Come and sit in the gallery.This involves the Orrong Group. The fact that this case has arisen is a consequence of commercially driven population growth in Victoria and Australia. The Supreme Court has changed the venue for the Hearing tomorrow, commencing at 10.30am. WHAT IS BEING CHALLENGED?- VCAT'S DETERMINATION :-

WHAT IS BEING CHALLENGED?- VCAT'S DETERMINATION :-

Recent comments