Anglophone press maintains depressingly low standard of reporting

The bias in Australian news reporting on Russia and the Ukraine is profoundly depressing. There is no responsible analysis of the role of the then 'opposition', with members now in parliament, and the use of snipers to fire at police and protesters alike in provoking President Yannukovych to temporarily leave the Ukraine. [Note I have removed the term 'resignation' because he has not resigned. I apologise for the confusion - Sheila Newman] 2 There is no acknowledgement of how elected President Yannukovych formally requested Russia's help - or it is mentioned as if it were specious. Although there was an election due within a year, Yannukovych was forced to flee in peril of his life by the forces that put the current illegal government in place. There is no acknowledgement of the validity of a 97% Yes referendum in Crimea to join Russia.3 There is no acknowledgement that Crimea already had separate administration within the Ukraine and that the great majority of its population identifies as Russian. There has been an over-emphasis on how a minority group of muslims said they had avoided voting and now complain that their needs were not met by the referendum and an underemphasis on how many voted and what they voted for. Little or no convincing evidence has been given for slurs implying that the referendum was either not legal or not well-managed. There is no acknowledgement of the reasonableness and democracy in calling a referendum, which is an example the increasingly undemocratic Anglophone West would do well to follow. There is hardly any mention in the Australian and other Anglophone press that the parliament of Acting President Oleksandr Turchynov, whom Obama greeted in the Whitehouse almost instantly 4 and whose government Australia supports in East Ukraine, contains six members with severe fascist and Nazi affiliations, which kind of explains how the use of snipers was part of the campaign to get rid of the elected government. The increasing evidence of US and NATO aligned Western powers provoking the Kiev coup is not being covered in the Australian and other Western press. There is also no mention that President Yannukovych had offered to bring on early elections to give the opposition a chance to win government legally. There is a constant use of the adjective 'aggressive' to describe Russia's actions in going, on invitation, into a largely ethnic Russian Crimea which had voted to rejoin Russia, in a region where European power-grabs threaten hard-won agreements between the many diverse countries involved in recovering and transporting oil and gas out of the Caspian Sea area.

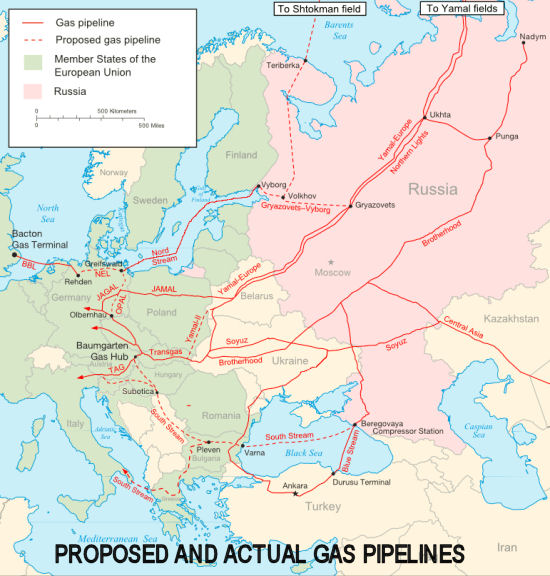

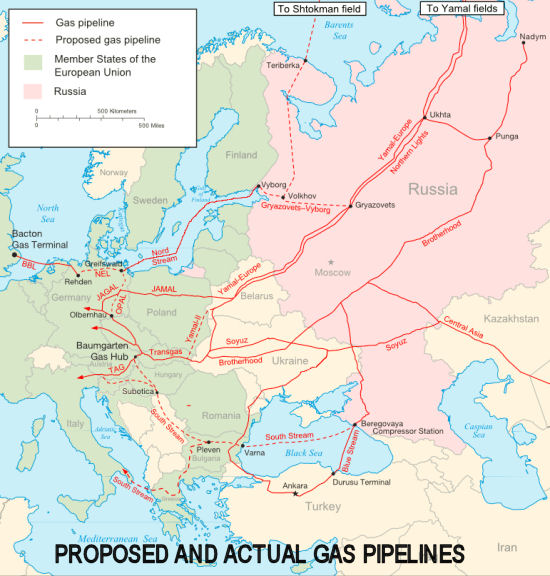

Oil and Gas in the Caspian region near Ukraine and Crimea

Most of all, there has been a glaring failure of Australian and US and other Anglophone news sources and governments to report that getting power over this region means getting power over major oil and gas reserves in the Caspian Sea and pipelines leading from its shared shores through several different countries with destinations as far as Britain 5 and China. That is why dividing the Ukraine up between Western Europe and Russia is such a big deal.

The Caspian Sea: History, political borders, rights to mine etc.

The Caspian Sea is the largest inland sea. "Geographically, it is a salt-water inland sea or lake covering about 375,000 square kilometres, bordered by the Elburz Mountains of Iran to the south and the Caucasus to the northwest. The Volga River flows into it from the north, forming a large delta near Astrakhan, but evaporation is sufficient to counter the influx, leaving it some 30 meters below world sea level. It is flanked to the north by Russia itself, followed clockwise by Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Iran, and Azerbaijan. The three "-stans” gained independence following the fall of the Soviets in 1991. Dagestan and Chechnya, which are still Moslem provinces of Russia on the shores of the Caspian, are still seeking their independence, in a vicious campaign attended by many acts of terror. Under international law, ownership of the offshore mineral rights depends on whether it is deemed a lake or a sea. In the case of the lake, they belong jointly to the contiguous countries, whereas in the case of a sea they are divided up by median lines. The matter, which is no small issue, has yet to be fully resolved, but it seems in practice to be moving in the direction of the latter formula. It is worth noting here that Tehran, the capital of Iran, lies only 100km from the Caspian shore, so its role in the future of the region cannot be ignored." (Colin Campbell, "The Caspian Chimera," Chapter 5 in Sheila Newman, (Ed)., The Final Energy Crisis, 2nd Edition, Pluto Press, 2008."

Don't the Australian public deserve to know of the many geological reasons why this area is so politically fraught, instead of being subjected to incredibly superficial theories of ego and ethnicity, when any explanation is offered at all for territorial sensitivity in the region?

There is a fabulous and apocryphal geopolitical context to this vast oil and gas-bearing region that is the Middle East and Eastern Europe. Russia started the first pipeline there in the 1880s in Baku on the edge of the Caspian Sea, with a pipeline which carried kerosene a total of 835km to the Batumi, Georgia, a port on the Black Sea. It was the longest pipeline in the world at that time. Joseph Stalin actually led workers in the oil industry there.

"In the late 19th century Baku on the Caspian Sea was the site of a pipeline to the Black Sea, financed by Rothschild and Shell Oil. Joseph Stalin was a workers' leader there in an atrocious working environment. By the end of the Second World War, established easily accessible wells in the Caspian were less productive and, although the Soviet Union continued some new development there, including the building of off-shore platforms, it focused more on inland resources which did not require investment in offshore drilling equipment." (Colin Campbell, "The Caspian Chimera," Chapter 5 in Sheila Newman, (Ed)., The Final Energy Crisis, 2nd Edition, Pluto Press, 2008.)

Since the late 19th century this area has been the object of colonial exploitation and wars over its mineral wealth, with British and US exploration teams competing against each other and against Russia. President Trueman's duplicitous policies towards Russia and Ukraine are the subject of Oliver Stone's Untold History of the United States series (book and films). (See interview of Peter Kuznik, Oliver Stone's co-writer on this material here.) The political behaviour towards the region by the US between the First and Second World Wars was eerily similar to its behaviour today.

These geopolitical features have bred extremely tough political survival behaviour in associated royal and elected governments. The toughness is expressed in authoritarian government and sophisticated international relations with commercial organisations, international finance and international governments. Since the first oil shock in the early 1970s, the oil-exporting countries in this region have attempted to shrug off colonial rulers and assert independence. The political countershock from the West has been to fight those attempts. Gaddafi led the formation of OPEC which coordinated the policies of the oil-producing countries, with the aim of getting a steady income for its member states in return for secure supply of oil to oil importers. His efforts assisted independence amongst member oil-producing countries and a world price for oil. There was a brief period when it seemed that the West might respectfully integrate the leaders of those Eastern independence movements and the oil producing countries, but draw-down on world oil resources, through increased demand and finite supply, ever more expensively accessed, has coincided with escalating aggression on the part of the west. Russia and China, for their parts, are acting defensively to secure their geopolitical links with their neighbours.

Pipeline-linked countries vulnerable targets

Most important in the new problems with Syria and Ukraine and Crimea, is access to pipelines conveying oil and gas resources from the Caspian Sea region through surrounding countries, which have strategic power and risks. The absence of reporting on this crucial aspect of East-West hostilities in the Western media makes the Western powers and their media promoters and corporate supporters look guilty and the populations of Western countries look uneducated and incurious. Coverage from the Teheran Times and Russia Today is far more reality based.

"The recent U.S.-backed coup that toppled the former government in Ukraine has been couched in the noble rhetoric of democracy, humanitarian intervention and self-determination, but a closer examination reveals an ugly underside of realpolitik whose motive is energy dominance. Like Syria, Ukraine has one of the key gas pipeline corridors coveted by the U.S. and its NATO allies that is still under the influence of a so-called R&D (resistant and defiant) country such as Russia.

To understand what is happening in Ukraine and Syria, and how Qatar and Azerbaijan are involved, we must briefly look at regional energy developments following the dissolution of the former Soviet Union. While the Persian Gulf is well known for its abundant energy resources, the Caspian Sea Basin also has seen oil exploration and production since the early 1900s however the U.S. and the West had scant involvement there before the end of the Cold War. Since the breakup of the former Soviet Union, the United States and Russia have engaged in fierce competition to control the energy resources of the newly created Caspian Sea littoral states." Source: "The last Argument of Kings," Tehran Times, March 18, 2014 by stratagem, http://www.phantomreport.com/pipeline-predicament-the-ukraine-syria-russia-u-s-gas-nexus"

Importance of who supplies China with gas

Russia's impending new contract to supply its neighbour China with gas for the next 30 years could be one of the things that caused Western powers to make desperate efforts at this time to get control of the Ukraine in order to influence oil supply contracts in the region. (Gazprom negotiations).

Supplying China has been an important goal of competing powers in the region because whoever supplies China has a very powerful friend. Even though contemporary oil-exploration is done by commercial corporations, states vie to develop and maintain relations with these companies. This need to dominate oil-exploration companies is likewise a major reason for US interference in South American and African politics and for South American states to make friends with Russian, Chinese and African states and their geo-exploration companies. Western powers are trying to destroy these alliances by using their own alliances which include supporting Israeli annexation of territories, amassing of arms, and Saudi Arabian attempts to religiously colonise free Arab states, like Syria.

We should all be trying to get along and to plan to downsize world economy in line with dwindling fuel resources, but half the world is doing the opposite.

State Politics and Fossil Fuel Depletion

There is no doubt that the world's industrial powers are encountering increasing trouble accessing affordable fossil fuel resources. All the signs are there: war, loss of democracy, environmental suicide.

A few years ago, the United States began using huge quantities of explosive material in order to crudely reopen old mines and start new ones in situations which it had not pursued before because of their inherent danger, pollution and landscape costs.

It is naive to accept the spin that the US puts on fracking for shale-oil and gas, by which it implies that it now has abundant fuels to supply growth indefinitely. The reality is that the U.S. has to spend more barrels of oil to get shale oil and gas than were ever required to get oil from wells. The reason the US is going after shale-oil and gas is because most remaining crude oil reserves are now very hard to get to, due to their inaccessible geological position and due to international political competition for these scarce resources. And getting shale oil and gas costs more than energy; it costs democracy and it has the capacity to ruin any resilience in the economy. See "Fracking Democracy". People are protesting across the US at how the government is permitting shale-oil and gas mines to take over their farms. They are afraid of pollution (notably of water), subsidence, and the truly awful scale of mining which is transforming landscape and politics, as well as air, soil and water, with massive emissions of carbon gases. Fracking has been banned in France, although the US-influenced EU is trying to overturn this, as it has overturned French law on use of hormone-based pesticides like Roundup and genetically modified crops. The Western powers have also tried to interest the Ukraine in giving them fracking rights in the Ukraine.

Profligate petroleum users have no place in the 21st century

Unfortunately Australia is unwisely following the United States style on fossil fuel recovery. The EU, which tended to have more conservative, longer-view plans, is at risk of being dragged into the same profligate style due to the growing influence of a US-influenced banking system on the EU and the debts which this has already caused in European countries.

Australia, the United States, and Britain, have all exhausted their petroleum reserves by pursuing policies of economic and population growth in the face of common sense. They have also used an expensive and inefficient commercial approach to exploring for and mining petroleum at home and abroad. As oil geologist, Colin Campbell, put it, western oil-explorers "had to pretend that every borehole had a good chance of finding oil" [in order to attract investors], whereas their Soviet counterparts, "were very efficient explorers, as they were able to approach their task in a scientific manner, being able to drill holes to gather critical information" - which meant that, due to being state-financed, they didn't have to sink lots of unproductive and costly wells.

Colin Campbell describes the difficulties of oil and gas mining in the Caspian Sea, explaining how the countries of the region exploited oil resources that could be more conventionally mined. Much of the oil and gas reserves there are, not only under the sea, but deep under the sea-floor:

"In the years following World War II, they brought in the major producing provinces of the [Soviet] Union, finding most of the giant fields within them. Baku [on the Caspian Sea] was by now a mature province of secondary importance, although work continued to develop secondary prospects and begin to chase extensions offshore from platforms. The Soviet Union had ample onshore supplies, which meant that it had no particular incentive to invest in offshore drilling equipment. The Caspian itself was therefore largely left fallow, although the borderlands were thoroughly investigated. Of particular importance was the discovery of the Tengiz Field in 1979 in the prolific pre-Caspian basin of Kazakhstan, only some 70km from the shore. Silurian source-rocks had charged a carboniferous reef reservoir at a depth of about 4,500 meters beneath an effective seal of Permian salt. Initial estimates suggested a potential of about 6Gb, but the problem was that the oil has a sulphur content of as much as 16 per cent, calling for high-quality steel pipe and equipment, not then available to the Soviets. Development was accordingly postponed. The fall of the Soviet regime in 1991 opened the region to Western investment. " (Colin Campbell, "The Caspian Chimera," Chapter 5 in Sheila Newman, (Ed)., The Final Energy Crisis, 2nd Edition, Pluto Press, 2008.

A more cautious Soviet approach and the difficulty of access due to cold climate has meant that Russia has not used up all its oil and gas supplies. It has a good record of efficiency in the surrounding region. Due to the depletion of traditional oil reserves, the time has come when oil-exploration in these dangerous and icy regions nearby Russia will find finance.

Population policies and entitlement to fuel resources

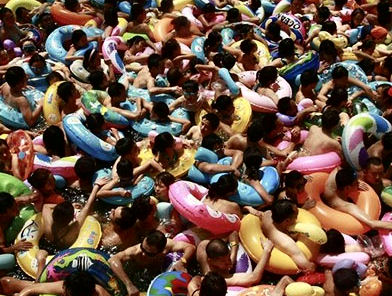

We could go further and say that, as long as the Anglophone countries insist on growing their populations and their economies - which really means growing their need for energy resources and their output of pollution - and starting wars to fulfill these unwise policies of continued growth - they don't deserve what they are going after. We maybe should include India which, like Australia, as an ex-British colony, has all the problems of the Anglophone system where focused beneficiaries of population growth promote it in flagrant opposition to public opinion. The only obvious solution to the problem of finite resources can be to share remaining scarce resources equitably among polities which agree to stop engineering growth and demand upwards. That is a way to avoid continuing wars. In contrast to the rapid population growth in Anglophone countries and India, Russia's population is not growing fast and China has a responsible population policy.

Fracking and western sabre-rattling in this region

The reason for the civil war in Syria almost certainly lies in the growing desperation by the United States and Europe about maintaining large supplies of cheap oil, in competition with China and Russia, with Russia relatively well-situated geopolitically. The United States trumpets its successful recovery through fracking as a cover but, as explained above, anyone who knows anything about oil knows that fracking oil and gas costs far more oil and gas than earlier methods of retrieving oil and gas, but the industries and governments just aren't revealing how much.

The two inland seas, the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea are the sites of major oil and gas exploration, although concerted exploration of the Black Sea is only just beginning, and expectations are modest.6 The reserves in the Caspian, however, are enormous, but the question is how much can ever be accessed and mined. These reserves are deep, dirty, dangerous and nearly inaccessible deposits laced with highly poisonous hydrogen sulphide, however they are sufficiently important for commercial and government exploration to have persevered, leading to the construction of extremely long pipe-lines to transport gas across multiple countries, from Baku, Azerbaijan to the Mediterranean coast of Turkey; from Baku via Russia to Novorossiysk on the Black Sea, thence to Western Europe. Accompanying the longest of these pipelines, the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan, which runs from Azerbaijan through Armenia and Turkey, to the South is Syria, Iraq and Iran, and, above them: Georgia, Russia and Ukraine, with Crimea just above Novorossiysk on the Black Sea. On the other side of the Black Sea is Ukraine, Romania and Bulgaria. On the other side of the Caspian Sea from the Russian side are Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan.

The recent coup against the legitimate Ukraine Government has meant that Russia now has to consider building a very expensive new pipeline around the top of the Ukraine to avoid new incursions into its territory bordering on the Caspian Sea.

You can see from the map, "Proposed and actual gas pipelines," (Source: Wikipedia commons circa 2007 but still useful) how difficult it would be for Europeans to impose economic sanctions on Russia, for Russia is an important supplier of gas to the rest of Europe. This is likely to cause a split between America, Saudi Arabia, Canada and Australia, which do not have this relationship with Russia. The United States has, however, recently begun exporting shale gas to Europe, creating an impression that it has huge supplies and hoping to reduce Russia's income from and power derived from supplying Europe in the short term.7 In the mean time, it seems the US is actually having problems supplying its own needs:

"U.S. Natural Gas Inventories

Natural gas working inventories fell by 74 Bcf to 822 Bcf during the week ending March 28, 2014. Colder-than-normal temperatures and a few late-season winter storms during the month resulted in increased heating demand, prompting larger-than-normal withdrawals. Stocks are now 878 Bcf less than last year at this time and 992 Bcf less than the five-year (2009-13) average for this time of year. Total stocks, as well as stocks in all three regions, are currently less than their five-year (2009-13) minimums." Source: Energy Information Agency, (EIA), http://www.eia.gov/forecasts/steo/report/natgas.cfm?src=Natural-b1

NOTES

1. ⇑ Sheila Newman's research thesis for environmental sociology, "The Growth lobby in Australia and its Absence in France" (pdf - 100,000 words plus) , was about differences in the way that Australia and France adapted their population, housing and environmental policies after the first oil shock. It contains an historical comparison of pre-oil shock oil-economics in both countries. Later she was co-editor for the first edition of Andrew McKillop and Sheila Newman, The Final Energy Crisis, Pluto Press, UK, 2006; and sole editor for Sheila Newman (Ed. and Author), The Final Energy Crisis, 2nd Edition, Pluto Press, UK, 2008, which is a collection of her work plus scientific articles by nine scientists in disciplines ranging from particle physics through agriculture to environmental science and one economist. In 2013 she published, Demography, Territory, Law: The Rules of Animal and Human Populations, Countershock Press, 2013. [Paperback and Kindle.] The second in the Demography Territory Law series: Demography Territory Law 2: Land-tenure and the origins of Capitalism in Britain, is due for publication by June or July 2014 and asks whether the confluence of coal and iron in Britain caused its massive population growth, assisted it, or followed on from it, whether capitalism was inevitable and why it happened in Britain rather than elsewhere in Europe.

2. ⇑Ramazan Khalidov and Takeshi Hasegawa, "Ukraine Opposition Behind Snipers in Kiev According to a Leaked Phone Call, Modern Tokyo Times, March 6, 2014; "Recorded call reveals Ukraine opposition snipers, not Yanukovych, fired on protestors in Kiev," PR News Channel, March 6, 2014: "In the second leaked conversation regarding Ukraine in as many months, two top-level diplomats have been recorded discussing a potential bombshell in the crisis in Ukraine.

According to The Guardian, the 11-minute conversation between EU foreign affairs chief Catherine Ashton and Estonian foreign minister Urmas Paet details new allegations that the snipers who killed protestors in the Ukrainian capital were not agents of former president Viktor Yanukovych, but rather agents of the opposition forces.

"There is now stronger and stronger understanding that behind the snipers, it was not Yanukovych, but it was somebody from the new coalition,” Paet said during the conversation. [...] "Following the declaration, Paet went on to mention that the new Ukrainian government has heard the evidence, yet has shown no interest in investigating the claims.[...]"

3. ⇑ Mark Byrnes, "Crimea's Controversial Election Day," The Atlantic Cities, March 17, 2014.

4. ⇑ http://www.platts.com/latest-news/natural-gas/moscow/gazprom-says-expects-to-sign-gas-supply-deal-26644803 Matt Vasilogambros and Marina Koren, "White House: In Meeting With Obama, Ukraine's Prime Minister Embraces the West"National Journal.

5. ⇑ The Nord Stream gas pipeline takes gas to Germany, from where it is transported to Britain and other countries. I am not clear as to whether there are still plans to continue the pipeline underwater to Britain.

6. ⇑ The Black Sea has nothing comparable to the proven reserves in the Caspian Sea, but the need to find oil and gas is becoming so pressing that companies have taken out exploration licences for gas reserves they would previously not have bothered with. The Skifska natural gas field located on the continental shelf of the Black Sea was discovered in 2012 and there are other promising deposits offshore from Ukraine. "At the helm of the new energy diplomacy effort is Carlos Pascual, a former American ambassador to Ukraine, who leads the State Department’s Bureau of Energy Resources. The 85-person bureau was created in late 2011 by Hillary Rodham Clinton, the secretary of state at the time, for the purpose of channeling the domestic energy boom into a geopolitical tool to advance American interests around the world."

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/06/world/europe/us-seeks-to-reduce-ukraines-reliance-on-russia-for-natural-gas.html?_r=0

7. ⇑ See Gail Tyverborg, "The Absurdity of US Natural Gas Exports", March 31, 2014, http://ourfiniteworld.com/

Putin's annual Q&A session 2014 (FULL VIDEO)

Tomorrow, Saturday 28 June 2014, thousands are expected to pour onto the streets to take a final stand against the monstrous $14 billion East West Link (EW Link) project about to be foisted on the long suffering people of Victoria by - in our view - the incompetent and increasingly unpopular Napthine Government. Demands of the rally are: scrap the E W Link Toll Road; rip up the contracts if/when signed; and invest in public transport.

Tomorrow, Saturday 28 June 2014, thousands are expected to pour onto the streets to take a final stand against the monstrous $14 billion East West Link (EW Link) project about to be foisted on the long suffering people of Victoria by - in our view - the incompetent and increasingly unpopular Napthine Government. Demands of the rally are: scrap the E W Link Toll Road; rip up the contracts if/when signed; and invest in public transport. Additionally the call has gone out for the Coalition to make the EW Link an election issue and to resist signing contracts before “the people” have spoken. Protestors will rally outside The State Library at the corner of Swanston and Latrobe Streets by 1 pm tomorrow, hear speeches and then march to Flinders Street Station.

Additionally the call has gone out for the Coalition to make the EW Link an election issue and to resist signing contracts before “the people” have spoken. Protestors will rally outside The State Library at the corner of Swanston and Latrobe Streets by 1 pm tomorrow, hear speeches and then march to Flinders Street Station.

In this report, Ernest Healy, spokesperson for the Moreland Planning Action Group, concludes that VCAT, together with the MCC, have created a precedent which overrides the intended meaning of government policy. He argues that the meaning of the Victorian government’s Policy on Commercial 1 zone can be interpreted to mean that, if the commercial potential of a commercial 1 site is poor, then its suitability for medium density residential development should also be deemed poor.

In this report, Ernest Healy, spokesperson for the Moreland Planning Action Group, concludes that VCAT, together with the MCC, have created a precedent which overrides the intended meaning of government policy. He argues that the meaning of the Victorian government’s Policy on Commercial 1 zone can be interpreted to mean that, if the commercial potential of a commercial 1 site is poor, then its suitability for medium density residential development should also be deemed poor.

In 2013 foreign investors obtained permission from the Victorian government to build or to buy 4,500 houses, amounting to some $18b worth of approvals. Numbers of houses falling into foreign hands are increasing, with the Chinese the biggest buyers and builders, followed by the Canadians, Americans and Singaporeans. There were 12,025 applications to invest in Victorian real estate according to an annual report for 2012-2013. Not one was rejected. On Wednesday 19 March 2014 the Treasurer, The Hon Joe Hockey MP, asked the Economics Committee to inquire into and report on Australia's foreign investment policy as it applies to residential real estate.

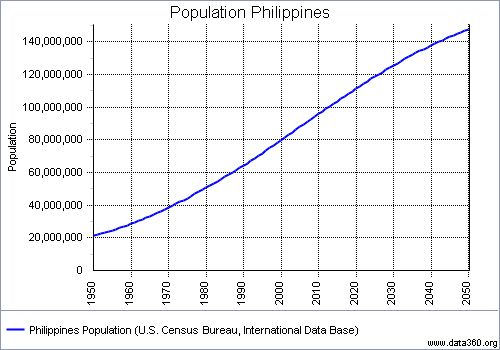

In 2013 foreign investors obtained permission from the Victorian government to build or to buy 4,500 houses, amounting to some $18b worth of approvals. Numbers of houses falling into foreign hands are increasing, with the Chinese the biggest buyers and builders, followed by the Canadians, Americans and Singaporeans. There were 12,025 applications to invest in Victorian real estate according to an annual report for 2012-2013. Not one was rejected. On Wednesday 19 March 2014 the Treasurer, The Hon Joe Hockey MP, asked the Economics Committee to inquire into and report on Australia's foreign investment policy as it applies to residential real estate.  For an Australia going the way of the Philippines, we should take heed. Rural Filipinos are being murdered by real estate developers. Even those who survived the recent typhoons are being

For an Australia going the way of the Philippines, we should take heed. Rural Filipinos are being murdered by real estate developers. Even those who survived the recent typhoons are being  Article-obituary first published at

Article-obituary first published at  Immigration policy in Britain continues to reveal depths of incompetence, as Europe is under increasing pressure from illegal immigration. Government claims that they are tackling the issues will do little to reassure a worried public.

Immigration policy in Britain continues to reveal depths of incompetence, as Europe is under increasing pressure from illegal immigration. Government claims that they are tackling the issues will do little to reassure a worried public.

"The geology of the region itself as well as its position as a geographical gateway to the Middle East, explains wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria, confusing dialogues with Iran and, now, moves on Ukraine. I really wonder if Australian politicians actually realise what they are backing in the region." Sheila Newman (Evolutionary sociologist specialised in oil geopolitics.)

"The geology of the region itself as well as its position as a geographical gateway to the Middle East, explains wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria, confusing dialogues with Iran and, now, moves on Ukraine. I really wonder if Australian politicians actually realise what they are backing in the region." Sheila Newman (Evolutionary sociologist specialised in oil geopolitics.)

Speakers: Jenny Warfe (Blue Wedges); Jenny Lowe (BirdLife); Dave Minton, Port of Hastings Development Authorities; Simon Brannigan, VNPA Marine spokesperson; Hugh Kirkman, Marine Environmental Consultant. Starts 5.45, Tuesday 15 April, Hastings Community Hub, 1973 Frankston-Flinders Rd, Hastings (booking essential) Westernport Bay is a site of international significance for aquatic birds and right on the doorstep of Melbourne. Its extensive intertidal mudflats, seagrass meadows, saltmarshes and mangroves support more than 10,000 migratory

Speakers: Jenny Warfe (Blue Wedges); Jenny Lowe (BirdLife); Dave Minton, Port of Hastings Development Authorities; Simon Brannigan, VNPA Marine spokesperson; Hugh Kirkman, Marine Environmental Consultant. Starts 5.45, Tuesday 15 April, Hastings Community Hub, 1973 Frankston-Flinders Rd, Hastings (booking essential) Westernport Bay is a site of international significance for aquatic birds and right on the doorstep of Melbourne. Its extensive intertidal mudflats, seagrass meadows, saltmarshes and mangroves support more than 10,000 migratory

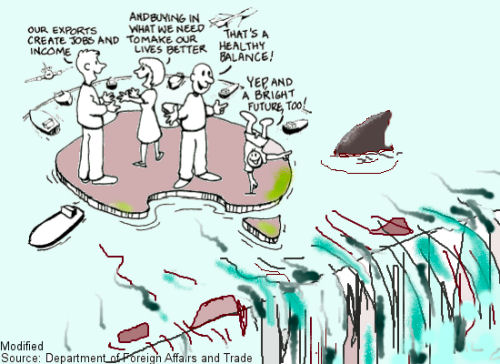

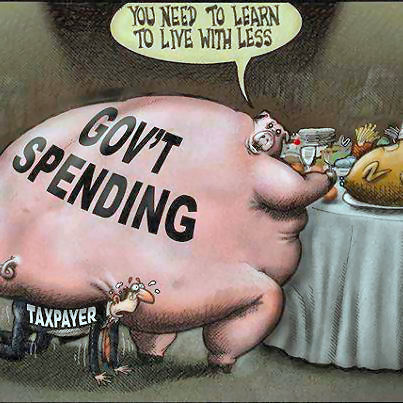

This article takes a quick look at some of Australia's sources of revenue and the costs of supporting our growing population. The numbers are frightening.

This article takes a quick look at some of Australia's sources of revenue and the costs of supporting our growing population. The numbers are frightening. The mining industry:

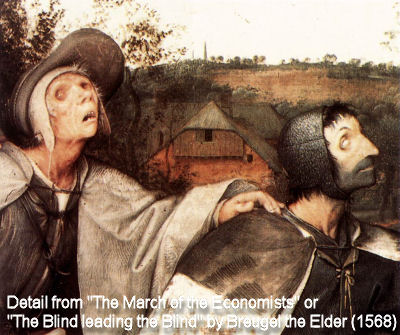

The mining industry: Economists advising Politicians on nation building are like the blind leading the blind. Historical facts prove that Australia's economy is managed by targeting consistent rates of extreme GDP growth. Let's define the facts before we review this problem. Economists and politicians apparently don't do this.

Economists advising Politicians on nation building are like the blind leading the blind. Historical facts prove that Australia's economy is managed by targeting consistent rates of extreme GDP growth. Let's define the facts before we review this problem. Economists and politicians apparently don't do this.

Definitions of Dictatorship:

Definitions of Dictatorship:

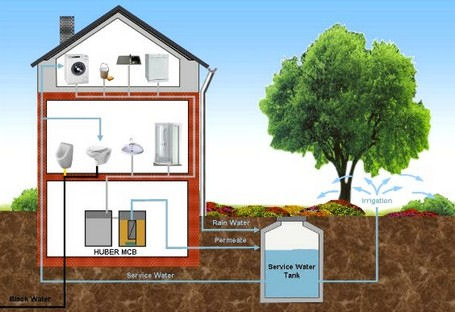

This research is significant for Australians who, with government engineered population growth causing rising water costs, are attempting to recycle water in many ways. "Researchers have identified that the use of wastewater to irrigate vegetable crops, which is common across developing countries, may significantly contribute to deadly health risks such as rotavirus, a major cause of diarrhoeal diseases." (Report from Melbourne School of Land and Environment)

This research is significant for Australians who, with government engineered population growth causing rising water costs, are attempting to recycle water in many ways. "Researchers have identified that the use of wastewater to irrigate vegetable crops, which is common across developing countries, may significantly contribute to deadly health risks such as rotavirus, a major cause of diarrhoeal diseases." (Report from Melbourne School of Land and Environment) “There can be lots of microorganisms that cause disease in wastewater. They can be transferred from infected people, travel through the sewerage system, and then be eaten from the vegetables. This is a dangerous cycle.”

“There can be lots of microorganisms that cause disease in wastewater. They can be transferred from infected people, travel through the sewerage system, and then be eaten from the vegetables. This is a dangerous cycle.” You are Cordially Invited to

You are Cordially Invited to

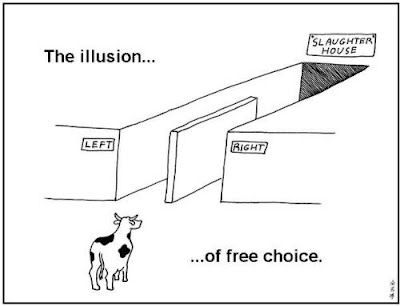

The political left-of-center is losing the war; learn from Scandinavian states "We are losing the war. And by we, I mean the politically left-of-centre; I mean the Labor Party and other social democratic parties around the world, I mean the trade unions, and I mean the environmental movement. We sometimes win battles, but overall we are not winning. I repeat, we are losing the war. We sometimes win elections, but usually on the terms of our opposition. We are in office, but not in power. And at all times we are fighting defensive, rearguard actions to protect the things we have achieved and built up—the social welfare safety net; industrial relations and workplace rights and protections; environmental protections and national parks; publicly owned assets; rules against the abuse of market power. Our opponents are emboldened and enjoy unprecedented media power." From a speech by

The political left-of-center is losing the war; learn from Scandinavian states "We are losing the war. And by we, I mean the politically left-of-centre; I mean the Labor Party and other social democratic parties around the world, I mean the trade unions, and I mean the environmental movement. We sometimes win battles, but overall we are not winning. I repeat, we are losing the war. We sometimes win elections, but usually on the terms of our opposition. We are in office, but not in power. And at all times we are fighting defensive, rearguard actions to protect the things we have achieved and built up—the social welfare safety net; industrial relations and workplace rights and protections; environmental protections and national parks; publicly owned assets; rules against the abuse of market power. Our opponents are emboldened and enjoy unprecedented media power." From a speech by

Federal Member for Wills, Kelvin Thomson, today said Monash University research which showed people in Coburg and Glenroy as vulnerable during heatwaves, highlights the need for more trees to be planted, and the risk from constantly adding more buildings.

Federal Member for Wills, Kelvin Thomson, today said Monash University research which showed people in Coburg and Glenroy as vulnerable during heatwaves, highlights the need for more trees to be planted, and the risk from constantly adding more buildings.

(Article by Sally Pepper)

(Article by Sally Pepper)

I am, together with a female I never met, excited to announce the non-birth of the son or daughter that was never conceived due to our proactive determination to ensure that outcome. This non-being was not born today on January 1, 2014, nor on any other day of our adult lives. Accordingly, nothing weighing 7 lbs. 14 ounces or any other weight issued from anyone's womb on that day or any other day on our account. And no grandfather, grandmother, uncle, aunt or sibling irrationally celebrated the arrival of a newborn simply because he or she shared their genes.

I am, together with a female I never met, excited to announce the non-birth of the son or daughter that was never conceived due to our proactive determination to ensure that outcome. This non-being was not born today on January 1, 2014, nor on any other day of our adult lives. Accordingly, nothing weighing 7 lbs. 14 ounces or any other weight issued from anyone's womb on that day or any other day on our account. And no grandfather, grandmother, uncle, aunt or sibling irrationally celebrated the arrival of a newborn simply because he or she shared their genes.

Jack Roach of Boroondara Residents Action Group (BRAG) writes that neither our federal nor our state governments can fund the infrastructure required to supply a doubled Melbourne population. The growth lobby, which includes the Labor opposition, is placing pressure on Mathew Guy to reduce residents' rights. The real problem is, of course, the unwise decision to grow Melbourne's population.

Jack Roach of Boroondara Residents Action Group (BRAG) writes that neither our federal nor our state governments can fund the infrastructure required to supply a doubled Melbourne population. The growth lobby, which includes the Labor opposition, is placing pressure on Mathew Guy to reduce residents' rights. The real problem is, of course, the unwise decision to grow Melbourne's population. "Plan Melbourne" has been criticized by the planning expert, Professor

"Plan Melbourne" has been criticized by the planning expert, Professor

Good news, but they still haven't got the technique quite right.

Good news, but they still haven't got the technique quite right.

Chair of the

Chair of the  The event took place today on Melbourne's Parliament House steps at 12 noon. Master of ceremonies, Rod Quantock introduced the main speakers - Jackie Fristacky, Mayor of Yarra, Jan Chantry, Mayor of Moonee Ponds, Tony Morton, president Public Transport Users' Association, Richard Foster, Melbourne City councillor, Greg Barber, Leader , Greens Party Victoria MP, Richard Wynne Shadow Minister for Public Transport , Brian Tee, Shadow Minister for Planning , Joe Edwards,West Parkville resident, Keith Fitzgerald, Collingwood resident. Members of community groups announced future events regarding the East West Link campaign.

The event took place today on Melbourne's Parliament House steps at 12 noon. Master of ceremonies, Rod Quantock introduced the main speakers - Jackie Fristacky, Mayor of Yarra, Jan Chantry, Mayor of Moonee Ponds, Tony Morton, president Public Transport Users' Association, Richard Foster, Melbourne City councillor, Greg Barber, Leader , Greens Party Victoria MP, Richard Wynne Shadow Minister for Public Transport , Brian Tee, Shadow Minister for Planning , Joe Edwards,West Parkville resident, Keith Fitzgerald, Collingwood resident. Members of community groups announced future events regarding the East West Link campaign.

The people of Western Sydney have been betrayed by the NSW Government after it was revealed (see bottom of page) they issued Lend Lease a licence that will allow the removal of all the Emus from the controversial former ADI Site. Despite years of protests by locals and their supporters further afield (see

The people of Western Sydney have been betrayed by the NSW Government after it was revealed (see bottom of page) they issued Lend Lease a licence that will allow the removal of all the Emus from the controversial former ADI Site. Despite years of protests by locals and their supporters further afield (see  “For nearly a decade all levels of government, specifically the NSW Government, have stated that Emus and Kangaroos would be retained within the proposed Regional Park. So this is a major betrayal to the people of Western Sydney” said Geoff Brown President of the Western Sydney Conservation Alliance and who led the ADI Residents Action Groups fight to save the ADI Site.

“For nearly a decade all levels of government, specifically the NSW Government, have stated that Emus and Kangaroos would be retained within the proposed Regional Park. So this is a major betrayal to the people of Western Sydney” said Geoff Brown President of the Western Sydney Conservation Alliance and who led the ADI Residents Action Groups fight to save the ADI Site. This article is about how parents should not use their status as an escape route from political participation, but should step up that participation. Katie observes that there is a tendency to opt out with the arrival of children amongst the middle classes, which have important capacity for political effectiveness. The author wonders how parents can fail to be motivated as the world they came into is disappearing before their children's eyes.

This article is about how parents should not use their status as an escape route from political participation, but should step up that participation. Katie observes that there is a tendency to opt out with the arrival of children amongst the middle classes, which have important capacity for political effectiveness. The author wonders how parents can fail to be motivated as the world they came into is disappearing before their children's eyes. "Populate and reap rewards," was Monday's

"Populate and reap rewards," was Monday's

This article is sourced from Protectors of Public Land Victoria. It is about the need to make submissions on East West Link at this point in process. Whilst she acknowledges the public lack of confidence in the process, Julianne Bell of the grass-roots but heavy hitting Protectors of Public Land Vic Inc. argues that making submissions is still important. She has supplied templates here to help submitters avoid the absurdity of reading hundreds of pages before submitting. Find at the end of the article: PPL VIC: East West Link (1) Template Statement to Assist Making Submissions on the Comprehensive Impact Statement on the East West Link (2) Cover Sheet to Accompany Submission 4.

This article is sourced from Protectors of Public Land Victoria. It is about the need to make submissions on East West Link at this point in process. Whilst she acknowledges the public lack of confidence in the process, Julianne Bell of the grass-roots but heavy hitting Protectors of Public Land Vic Inc. argues that making submissions is still important. She has supplied templates here to help submitters avoid the absurdity of reading hundreds of pages before submitting. Find at the end of the article: PPL VIC: East West Link (1) Template Statement to Assist Making Submissions on the Comprehensive Impact Statement on the East West Link (2) Cover Sheet to Accompany Submission 4. A report released by the Federal Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics underlines just how inadequate and incompetent Melbourne’s recent planning has been.

A report released by the Federal Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics underlines just how inadequate and incompetent Melbourne’s recent planning has been.

Monash University Professor of Public Transport Graham Currie said any city growing in population without expanding public transport was planning for decline. He said “the future cupboard of public transport projects is looking bare” and that “If population grows by 25% but services remain essentially static, we have a per capita decline of 25 per cent in service levels. We are not responding to growth. Rather we are going backwards”.

Monash University Professor of Public Transport Graham Currie said any city growing in population without expanding public transport was planning for decline. He said “the future cupboard of public transport projects is looking bare” and that “If population grows by 25% but services remain essentially static, we have a per capita decline of 25 per cent in service levels. We are not responding to growth. Rather we are going backwards”. Geoff at Aussiebushtreks writes, "This is very urgent. Please watch Corine Fisher's video. [Inside article]" Then Email upper house pollies without delay. There is still a chance to stop O`Farrells dreadful destructive Planning Law. If you go to

Geoff at Aussiebushtreks writes, "This is very urgent. Please watch Corine Fisher's video. [Inside article]" Then Email upper house pollies without delay. There is still a chance to stop O`Farrells dreadful destructive Planning Law. If you go to

Recent comments