Pages: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10.

Contents: What is known about real democracy?, What should be the shape of contemporary democracy?, Ensuring democratic consensus.

Editor's preface: It has long been apparent that whilst Australia is governed under a nominally democratic system, virtually all of the decisions which affect our every day lives are not arrived at democratically out in the open by ordinary Australians.

If this were not so, then where, for example, was the decision to privatise Telstra discussed and agreed to by the Australian public? Certainly not in the 2004 elections where politicians in favour of privatisation studiously avoided any discussion of the issue.

Then, in September 2005, with at least 70% of the Australian public opposed, our elected Federal Parliamentary representatives, nevertheless, rammed through the Telstra full privatisation bill, thereby causing almost incalculable harm to the interests of the Australian public, Telstra's customers and its workforce in subsequent years.

So, if the decision that it was a good idea to Telstra was not arrived at by ordinary Australians out in the open, then where was it decided?

As the idea clearly didn't just drop out of the sky, it can can only have been arrived at, behind closed doors by powerful vested interests who stood to gain at the expense of the rest of the community.

Similarly, many other policy decisions, also opposed by the public and against their interest, must have similarly been arrived at behind closed doors - the privatisation of QANTAS, and the Commonwealth Bank, the privatisation of retirement income, the deregulation of the finance sector, the dismantling of protection of Australia's industrial base, the imposition of high rates of immigration, etc.

Tony Ryan's article of 2007 shows how the ideals of democracy, articulated prior to the American Revolution were undermined to suit the interests of the small wealthy global elite, whose descendants largely in control of our destiny today. Today, this group includes the Rockefeller and Rothschild families, the seven global media owning families and corporations, particularly Warner, MGM, Time-Life, Disney and Rupert Murdoch.

Whilst this view of history may seem novel to many, and is, indeed, fairly new even to me, past American Presidents such as Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson were aware of how the antecedents of today's banking and media elites pulled the levers of power from behind the scenes. Roosevelt termed them the Invisible Government1.

The article also shows how effective democracy should work, where it still operates today and where it has in the past historical times.

If this is not democracy - then what is?

by Tony Ryan

Every day, we hear references to democracy: parliamentary democracy, Westminster democracy, Australian democracy, representational democracy, and democratic majorities. And, of course, we have America's special legacy to the burning nations it recently invaded and occupied? George Bush's freedom and democracy.

These phrases are calculated misrepresentations; what we should more accurately describe as products of public relations, propaganda, indoctrination, misinformation or brainwashing; depending upon preferred vocabulary. What we must become reconciled to is that this word, in the context of contemporary politics, has nothing to do with genuine democracy.

... Kevin Rudd... routinely overrules 80% of Australians in virtually every issue, while obsequiously positioning himself to be the President of China's new Australian colony.

As for we Australians, one would not be in cerebral overload if one wondered about the meaning of Kevin Rudd's cherished Australian democracy, while he routinely overrules 80% of Australians in virtually every issue, while obsequiously positioning himself to be the President of China's new Australian colony.

This is the same "democracy" that the US has trumpeted loudly while it plundered the resources of the 43 sovereign nations that it militarily invaded since 1946; overthrowing governments supported by the overwhelming majority of inhabitants.

Once examined more closely, it is not difficult to conclude that this version of 'democracy' is not compulsively desirable; a conclusion which has led many of the world's youth to declare that "democracy is not what it's cracked up to be". Of course, what they disparage is not democracy at all. They are justly criticizing various forms of representationalism, in which people are ruled by elected politicians, or by oligarchies or dictators.

What all of this demonstrates is the devastating impact of media-borne propaganda.

The more logical conclusion; that politicians who are otherwise noted for their lies, distortions, oppression, hegemony, torture and genocides, would be most unlikely to favour Government of the people, by the people and for the people, somehow does not occur to us.

Although popular media and government-owned TV stations never discuss this, the truth is that the source of this anti-democracy propaganda is highly organized and extremely well resourced; a fact now recognised on thousands of Internet sites; the only truly free media.

This powerful source of misinformation is a loose consortium of international bankers, led by the Rockefeller and Rothschild families; and by the seven global media owning families and corporations, particularly Warner, MGM, Time-Life, Disney and Rupert Murdoch. These represent an even more camouflaged elite who are united in the belief that they are born to rule the world. This is allied to the ancient aristocracy, who were largely forced underground by the French, American and European Revolutions and by subsequent universal rejection of inherited political and economic power. By 1850, with the Rothschild link with America's plutocracy forged, this became the manipulating power behind governments whose presence most of us have become vaguely aware of in more recent times.

What few have ever suspected is the vast extent of wealth that finances public indoctrination in every nation; literally trillions of dollars. For example, as readily and publicly admitted by David Rockefeller, all spontaneous social movements that have emerged since 1970, no matter how legitimate their cause, have been subsumed and manipulated to serve the objectives of one part of this elite or the other. Thus it was that the women's movement of the late 1960s, very reasonably demanding equal rights and equal opportunity, became suddenly diverted into a drive to replace men altogether and to promote the concept of the single family. This anthropological coup was easily managed by the media and orchestrated by compliant politicians and by the United Nations; which was, we should recall, established by the Rockefeller family.

Contrary to the peace-seeking vision of the UN presented to us by our gullible and well-indoctrinated school teachers, the United Nations was established by Nelson Rockefeller, and its headquarters installed on Rockefeller-owned land in New York. Moreover, the funds managed by the UN agencies: the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the Bank for International Settlements, are owned and controlled by the same Rockefeller-Rothschild alliance. And the US Federal Reserve, like all other institutions around the world, including the Bank of England, are all owned by these same entities; who also direct the activities of the World Trade Organisation.

Thus it has been, that all apparently spontaneous social movements; such as multiculturalism, refugee rights, gay rights and feminism, have been funded and controlled by the global political elite. David Rockefeller does not deny this, and is, as he said, "proud of it".

The corporate motivation for its part in social manipulation is recognition that family and democracy are the prime units of social cohesion of all societies, and are the sources of values seen to be in direct conflict with globalist corporate ambitions. Very correctly, parents have been identified as the high priests of respect, love and loyalty, and are the genesis of all consumer resistance; therefore parents are the declared enemy.

In retrospect, we may see that since the establishment of the United Nations, national government's have become oligarchic, authoritarian and elitist; and policies increasingly violate the real rights of parents and children, whilst pretending to create these rights. Accordingly, the state is gradually assuming control and responsibility for child nurturing. In more tangible terms, since the UN brokered the termination of dedicated teachers training colleges, this role has been delivered to universities that are now mere appendages of UNESCO; with the primary objective of training teachers and social workers to severe the intergenerational transfer of values.

We may readily appreciate that the primary obstacles to the corporate-desired New World Order are Family and Democracy. This is the reason why the meaning of the word democracy has been under sustained attack, successfully reversing the meaning in many people's minds, from government by electoral consensus, into government by elites who purport to represent the people.

Most assuredly, in the not too distant future, we will hear that 'democracy' has failed and must be replaced with something more practical; like a benign world dictatorship.

The promoters of the new philosophy are somewhat coy about the language used to describe their vision of the future, but disillusioned insiders have described it as neo-feudalism; a return to the age of lords and serfs.

Very clearly, we would be wise to review this situation and calculate where our social and historical navigation went wrong.

The first question we should ask ourselves is what do we really know about democracy? Unfortunately, books on the subject appear to have disappeared from public libraries, so the prevailing confusion is eminently understandable.

Our oldest record of democracy goes back to ancient Greece, which in fact was only a partial democracy wherein a mere 18.5% of the population had the right to vote. All other people; that is, all women, children, aliens and slaves had no right to vote. Only men, both of whose parents were Athenians, were eligible. But even this information is being obscured. Wikipedia and other popular sources of information provide a distorted version of this history.

We are discouraged or prevented from learning about historical democracies because for the ruling elite this is an inconvenient truth. Nevertheless, imperfect as Greek democracy was, we should not simply dismiss it as irrelevant. The Athenians utilized democracy's essential principles and, as a result, were politically and culturally ascendant for four remarkable centuries.

What is omitted from mainstream knowledge is that the ancient Greeks had a culture within which a major determinant for action centered on the powerful ethic of actively representing their countrymen and women.

Thus, voting councilors felt irresistibly compelled to visit their family and vassals and reveal their constituent's true feelings and aspirations regarding the current circumstances and future of Greece. There was considerable pride in achieving this level of representation, and implacable contempt for those who could not. We gain the most enlightening insight into their values, and to the extent of historical distortion, when we read the funeral oratory of Thucydides, following the death of Pericles.

"We do not copy our neighbours (other nations), but are an example to them. It is true that we are called a democracy, for the administration is in the hands of the many and not of the few.

But while the law secures equal justice to all alike in their civil disputes, the claim of personal excellence and integrity is also recognised; thus, when a citizen is in anyway distinguished, he is appointed to the public service, not as a matter of privilege, but as the reward of merit.

Neither is poverty a barrier. A man may contribute to the uplifting of his country regardless of the obscurity of his origin or circumstances. We are prevented from doing the wrong thing by respect for the authority of the nation and for the laws, having a special regard for those which are initiated for the protection of the aged and the infirm, as well as to those unwritten laws which bring upon the transgressor of them the stern reprobation of the community.

An Athenian citizen does not neglect the state because he is committed to his own affairs; and even those of us who are preoccupied with commerce have a very fair idea of politics.

We alone, of the peoples of the world, regard a man who takes no interest in public affairs, not as a harmless person, but as a useless character. And, even if few of us are original thinkers and initiators, we are all sound judges of policy".

What would Thucydides think of our noble Australian manhood, whose thoughts rarely divert from football or cricket; or our fair ladies as they immerse themselves in the wisdom of Cosmo or New Idea? And, to those foreigners who bray a derisory laugh, is there not a pervading demographic equivalent in every western nation?

What made ancient Greece great was that this quasi-democracy, reinforced by a culture of almost obsessive consensus, was able to harness the entire knowledge, experience and wisdom of its citizenry. The power of this is incalculable, but not unknown; we call it people power.

Utilising people power, Greece was able to defeat the mighty Persians, who were handicapped by a hierarchy with all power at the top; a scenario which ensured sycophancy and corruption.

Sound familiar?

In spite of contemporary elites repressing our knowledge of history, it is still possible to read about other great democracies. The Irish Monks were our great first-millennia documenters, and most of us harbor vague recollections of these people, but few of us are aware that most of these monks were married and had families, and about a third were women; and the greatest monk of all was a woman (somewhat giving the lie to the historical revisionism of Rockefeller's divisive feminists).

This was Greater Europe of the 4th to the 9th centuries; a time when Ireland alone rescued and preserved all knowledge of ancient Greece and Rome, and was the cultural hub of Europe. The Monks traveled the known world, recording cultures, knowledge and collected wisdoms and dispersed these amongst all peoples. Ireland of this time was a democracy; the kings, inherited clan chieftains of old, were the administrators and executives, but their role was exclusively the implementation of the will of the people. A similar regime operated in then contemporary Finland, and is still echoed in the culture of the Sámi.

This Age of Enlightenment and Peace was terminated by the Holy Vatican of Rome, firstly when it imposed celibacy on the Monks; then with the violent launching of a regime of enforced ignorance, repression, poverty, torture, hegemony, ritualised execution (burnings at the stake and garroting) and institutionalised war and genocides.

Although the Vatican has been anxious to forestall even the most casual of glances at the first millennia Age of Enlightenment, by shrouding this era with the designation, Dark Ages; in fact, the true Dark Ages commenced with the defeat of European democracy and continued for more than a thousand years. This was a time of debauched and murderous Popes, as many as four ruling in competition during one period, and the theft of the wealth of all prosperous people, under the guise of eliminating heretics.

Rome continues to wage a global war against democracy, even in Australia (ie the overturning of the NT's voluntary euthanasia legislation, supported by 90% of the NT population). And, in collaboration with the CIA, there was the assassination of the thirteen South American rebel priests who had established Liberation Theology, which redefined Christianity as defending the poor from exploitation by the rich.

The European democracies, as did ancient Greece, embraced many millions of peaceful citizens over a period of four hundred years; which speaks persuasively as to the efficacy and practicality of consensus government. However, the Greek and European democracies were both preceded by eminently more purist models. By looking at the cultures of Australian Aborigines, the Kung of Africa and the Inuit of the far northern American continent, we can observe that democracy is actually the natural continuity of human social organisation.

We would do well to at least glance at these cultures; and where else for we Aussies but at Australia? We will present some detail here because it may balance in some way the diminished, trivialized, politicised and degraded version of culture presented by the pseudo Aborigines who now dominate the media.

... few Australian anthropologists bothered to learn Aboriginal languages. This entirely discredits their interpretations of Aboriginal culture.

While this brief article has no interest in launching anthropological civil war, it should nevertheless be recognised that, unlike their colleagues in every other country in the world, few Australian anthropologists bothered to learn Aboriginal languages. This entirely discredits their interpretations of Aboriginal culture.

It is not possible to develop an insight into an alien culture without first learning its language(s). The Pidgin English used instead was, and is, entirely useless, as was pointed out by eminent and conscientious anthropologist, Elkin, some seventy years ago. Little wonder modern anthropologists and black arm-band historians2 vilify him.

However, a few ordinary Australians did try to learn languages and these people developed a picture entirely at variance to the academic model. One of the insights to emerge was of a non-hierarchical people who made decisions by initiating consensus protocols. These operated simply and very effectively on a single principle: all decisions involve focus on a geographical location, therefore the person whose spirit had its origins in that location launched the consensus process. Because each person's personal name denoted his spiritual origins (and still does), ascription was easily identified.

Initiating consensus simply requires verbalising the essential question by the person with the appropriate name (the consensus process designate). This usually takes the form of neutral references to supposed advantages or disadvantages of the full range of options and becomes the signal for every man, woman and child to commence discussion.

In traditional Aboriginal culture, unilateral decision-making was entirely alien, as were power hierarchies.

The protocol initiator will eventually observe that absolute consensus has developed, and he will formally announce the community's consensus. In traditional Aboriginal culture, unilateral decision-making was entirely alien, as were power hierarchies. As in all cultures, through personal achievement, and even age itself, certain people most certainly developed higher status, but this was not applied to decision-making.

It is understood that the African Bushmen and Inuit used similar methods; perhaps, considering the evidence of known history, equally purist in application. The implications are that, during human prehistory, democratic methods of social organisation were the norm, and hierarchical systems were a later aberration, always with highly unpleasant consequences. (As an oblique but interesting aside, these democratic cultures were also devoid of personal neurosis and many other social and emotional afflictions erroneously regarded by social scientists as endemic to all peoples).

More recently in European history, an Englishman, Thomas Paine, wrote a series of books about democracy, the best known of which was The Rights of Man. With admirable perception, Paine identified hierarchies as the cause of all man's woes and his then very popular writings meant the death knell of aristocracies; against whom all of Europe subsequently rebelled. His inspiration also provided the rebellion movement with horizons and direction and, more importantly, identified in advance that peace and prosperity can only become an outcome if all authority derives from The People.

The Rights of Man was the prime influence that countered the exasperating excesses of England's George the Third and those of Louis xvi of France, both of whom claimed divine right to rule. Paine's thoughts provided the inspiration for the original drafts of the French and American Constitutions.

The aristocracy and merchant plutocrats moved swiftly to defeat this movement and, thenceforth, an intensive regime of censorship has operated in almost every country; which continues to this day. We may regard this as the commencement of what has come to be known as pursuit of the New World Order; a fine-sounding euphemism for return to raw feudalism in which an all-powerful elite will rule over a uniformly-impoverished humanity.

The key to manipulation was in ambiguous use of the word

representation, through which direct

rule by the people later delivered to a parliament by their elected representative; became direct rule by elected representatives.

The key to manipulation was in ambiguous use of the word representation, through which direct rule by the people (consensus), later delivered to a parliament by their elected representative; became direct rule by elected representatives (representationalism).

Therein, we have been tricked into electing corrupt and manipulated politicians to do our thinking for us. Moreover, if these politicians represent political parties, as approved candidates they are selected and vetted for future compliance by the entities that provide election campaign finance. These entities are led by the very bankers and media owners who created the New World Order agenda. To complete the illusion of choice, we are provided with dually-funded Tweedledum/Tweedledee major political parties.

These acts of philosophical sabotage were the product of Paine's single miscomprehension; inasmuch as he ascribed the rights of man to the Christian God; explicitly, that God created all men equal. The exploitable weaknesses of this notion were:

- That it meant nothing to non-Christians;

- That the Christian Church organisations were innately hierarchical and, moreover, enthusiastically supported the imposition of ignorance and poverty on the masses; and

- That, manifestly, people are not born equal. Many are already disadvantaged by being the product of unhealthy mothers, thereby impinging on their intelligence, health, immuno-systems and capacity to survive and be productive. Moreover, being born into wealth provides elites with an immediate advantage.

Unfortunately, Paine failed to realise that adoption of three stand-alone axioms of law would have established the desired equality:

- Informed Electoral Consensus;

- Equal Rights; and

- Equal Opportunity.

Already by 1792, seizing their opportunity, the Jacobins had hijacked the French Revolution and the new Constitution. Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, the ruthless American plutocracy, otherwise known as the revered Founding Fathers, through their agent James Madison, excised all references to democracy in the Declaration of Independence and in the US Constitution. The entire rights of man were watered down to a vague and futile pursuit of happiness. Later, some scholar drew attention to the desecration and ten subsequent amendments were eventually implemented in impotent and piecemeal disarray, ironically to become known grandly as the American Bill of Rights, embarrassedly emulating the British act of 1688. A more appropriate title would have been a very upper case "Ooops!" As the absolute hollowness of the American Constitution became apparent, the number of amendments eventually totaled twenty-seven.

The cherished belief that American colonials had a vision of democracy is a promulgated distortion. The ordinary people did indeed envisage democracy as presented by Thomas Paine, and with great joy and anticipation; but their leaders were horrified by the prospect. In fact, they initiated an unworkable modeling of a presidency based loosely on the role of the British Monarch, but with more executive power; and with two incompatible houses of parliament which served to frustrate the wishes of the people.

The United States of America is not, and never was a democracy and the word democracy does not appear in any of its enabling documents.

The US is a plutocracy; a regime of the wealthy elite; which employs an oligarchy to pursue its interests. The American people are taught what to believe by the Plutocracy, as is the less ingenuous oligarchy; which the people harangue futilely hoping it will obey their wishes.

As we snicker at American naiveté and gullibility, we should become more sharply aware that democracy plays no part in our governments either ...

As we snicker at American naiveté and gullibility, we should become more sharply aware that democracy plays no part in our governments either, and neither is democracy mentioned in any of our enabling documents. We, too, have been deceived.

Since 1850, when the fifth son of Mayer Rothschild finally linked the US Plutocracy to the Rothschild's European banking empire, the drafting of all laws and constitutions has been contained and directed by the globalist elite, through their local servants in each national community ... the hierarchy we know of in Australia as the Law Society.

To understand real democracy, we need to sweep away the mountain of academic and journalistic garbage under which real democracy has been buried.

To understand real democracy, we need to sweep away the mountain of academic and journalistic garbage under which real democracy has been buried. As the KISS adage suggests, we should keep the explanation simple, because genuine democracy is indeed simple; as we shall see:

All politics is about power.

Power in the hands of the people is democracy. Power in the hands of any minority or group is not democracy. What minority control may well be is oligarchy, theocracy, monarchy, aristocracy, plutocracy; or any of the specific variants on this theme; but none of these can be described as democracy. In terms of the much abused spectrum of politics (left and right politics): left is power distributed evenly throughout the people; right is power redistributed to a minority; a minority of many, or of one.

Just for the record, Karl Marx despised democracy and recommended a system of bureaucracies (centralisation of power to committees), which inevitably evolved to dictatorships. No other destiny was possible; therefore communists/socialists are right wing3, not left wing; as the elitist manipulators of knowledge would have us believe. This confusion is deliberately promulgated in order to blur our perception of genuine democracy.

Fabian socialists too, are right wing, believing that government should be subsumed by stealth and manipulated by a knowledgeable elite; and that government should wield power on behalf of the people. Kevin Rudd, for example, is a Fabian socialist; as was Bob Hawke. The still-incredulous should observe that the globalization launched by Hawke and Keating was resumed seamlessly by Howard and Rudd. All aspire to the same dictatorial New World Order. Howard's support of Monarchy merely reflects his acknowledgement of an older path to a common goal.

Their convergent objective has always been to make Australia subordinate to a world dictatorship; variously referred to as World Governance or New World Order depending upon perspective. New Zealand's Helen Clarke is of the same ilk, even more ambitiously anticipating her United Nations reward to be the Secretary Generalship

.

Regardless of apparent political colours all political parties, including the Greens4, are directed by the same banker/media elite, led by the Rockefeller and Rothschild families, and closely allied to Rupert Murdoch. Regardless of claims, all political parties want to erase democracy forever and this real agenda is exposed in their failure to acknowledge the will of the majority of Australians on almost any issue. This programme is global; however Australia is on the 'urgent attention' list due to its capacity to be self-sustaining economically, and therefore capable of walking away from the NWO plan.

It should be recalled that the duplicity of power-mongers has long been observed and that much of what I am saying is not new. With incisive perception, Lord Acton analysed the multitudinal betrayals of the people and concluded that there are no great leaders, only bad men, and that these manipulators subsequently arrange for history to portray them in a flattering light. He also wisely noted that Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely, thus pointing out the freedom-destruction of the representationalism that the Rockefeller/Rothschild cabal has so fraudulently but successfully been superimposing on our understanding of democracy

.

We should be uncompromising in our understanding here. Democracy is government of the people, by the people and for the people. Anything else is simply not Democracy.

So, what does this mean in terms of more desirable political structures?

This is quite simple. We, the electorate, following considered exposure to all the relevant information, should decide the direction and thrust of policy. Those of us who wish to busy ourselves with the nuts and bolts of policy implementation are fully entitled to do so, although most citizens would back away from such details.

Something approximating this process occurred in 1967, when Australians overwhelmingly supported a referendum over Aboriginal inclusion in national census and statistics. Although politicians remained hopelessly divided over the issue, prompted by Aboriginal rights activists, the people discussed it in depth for a decade and inevitably found overwhelming consensus.

In a democracy, electoral consensus should be conveyed in documented form to Parliament, wherein this consensus flows and melds with the consensus of other electorates, and is subsequently implemented by the Public Service. It is not necessary for electorates to deliver identical or even similar policies. For example, the water conservation policies of the Murray-Darling Basin electorates would be meaningless on Australia's northern monsoonal coastal electorates. Similarly, administrative accommodation of Aboriginal languages in the northern cultural triangle demarcated by Pitjanjatjara northern border SA, the Kimberly and NE Arnhem Land would be pointless elsewhere, where English is clearly the dominant or only language of Aborigines.

In fact, national uniform laws only function effectively where circumstances are identical in implementation.

The role of politicians requires redefining, after several decades of escalating abuse. In a genuine democracy the role of politician is tantamount to that of message boy; albeit a trusted and broadly knowledgeable one; consensus coordination. It is not the politician's function to deliberate on or to preempt electoral decisions.

In pursuit of this consensus coordinating role; and at least until a culture of democracy is imbedded in Australia, each candidate should sign a contract with his electorate to convey to parliament only the informed and documented consensus of that electorate. The candidate must also pre-sign an undated letter of resignation, which the electorate can activate in the event of betrayal. These are effective and realistic protections against the megalomania, messiah complex and corruption that inevitably afflict all contemporary politicians.

Contrary to hierarchical propaganda, any competent survey of the electorate today will reveal that, even on issues in respect of which the people have not had access to sufficient information, there is near-consensus of 70% to 90%+ on almost every important issue. Polls that indicate otherwise are manipulated.

Although we have merely touched on the empowering phenomenon of democracy here, a single item of Globalist propaganda will demonstrate the full extent of our indoctrination, and of our cultivated and unquestioning acceptance that absolute non-democracy is nevertheless democracy:

We all routinely accept the defining legitimacy of the statement that a 51% vote constitutes a democratic majority, yet a 49:51 division is actually clear evidence of absolute division in the community; hardly a desirable circumstance, nor one through which we should proceed without the certain knowledge we are courting disaster and failure.

How did we accept without question, such a transparent oxymoron?

There are some fifty beliefs about government that are just as illogical and invalid, yet these too are accepted globally as self-evident truths. We will present all of these on our sister Internet site, oziz4oziz.com wherein all contemporary issues will be presented as objectively and honestly as availability of information permits.

Consensus democracy is no mere ideal. It is axiomatic that any 1000 people share more collective wisdom and knowledge than any single person or 'leader' no matter how extraordinary this person's range of knowledge may be. Moreover, the 1000 people have counter-balancing experiences, whereas the values and emotions of the single leader are inevitably distorted by specialisation and demographic positioning.

In a genuine consensus democracy, the nation has access to the accumulated wisdom and knowledge of the entire adult population; a vastly superior resource to that possessed by a handful of inevitably and invariably megalomaniacal leaders.

Although the reinstallation of democracy is presented here almost hypothetically, in fact a substantial organisation already exists that is marching in this direction. This is the Tariff Restoration Bloc (TRB - see http://www.oziz4oziz.com), which represents almost all small parties and independents in Australia on the single and unanimously agreed-upon issue of restoring tariffs. No other issue is discussed; which obviates any possibility of disunity. Moreover, this is a leaderless movement and it operates through cell structures. Updated information is distributed radially to 80 immediate representatives, who in turn distribute communiqués (The Chronicle) to their own members or member organisations.

Readers wishing to be place d on The Chronicle Bcc e-mail list can contact tonyryan43 [ AT] gmail.com.

Footnotes

1. ↑ At an address to the Progressive Party in Chicago on 6 August 1912, then ex-President Roosevelt stated, "Behind the ostensible government sits enthroned an invisible government owing no allegiance and acknowledging no responsibility to the people. To destroy this invisible government, to befoul the unholy alliance between corrupt business and corrupt politics is the first task of statesmanship of the day." - cited in Towers of Deception - the media cover-up of 9/11 (2006) page 225 by Barrie Zwicker.

2. ↑ I was surprised to learn that Tony Ryan is harshly critical of 'black arm-band historians'. I, myself, broadly accept what is labelled the 'black arm-band view' of Australian history. Nevertheless, Tony has lived in the Northern Territory amongst Aboriginals for decades, and is fluent in a number of Aboriginal languages, so I accept that his views are derived from a thorough grasp of Aboriginal culture and a genuine concern for their welfare. - JS

3. ↑ Whilst I have been far from uncritical of the political movement known as Marxism (see, for examples articles in "socialism"), I would still question Tony's characterisation of all adherents of Marxism including, for example Sandy Irvine as being automatically authoritarian and right wing - JS.

4. ↑ In fact, the stance of the Greens has coincided with the popular will on many occasions in recent year. As one example, NSW upper house MP John Kaye was one of the leaders of the successful campaign against the privatisation of NSW's electricity in 2008. This does not mean that the Greens are without serious flaws, particularly in Queensland where I live, but I have yet to be convinced that they are being "directed by the ... banker/media elite" as Tony asserts. - JS

Pages: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10.

Copyright Tony Ryan 2007

1) Much of the fire burnt most intensively through dry forest with euc species such as Euc radiata and Euc dives. These trees have no market value for the logging industry and usually no logging takes place in them. On the Modis fire satellite image, the fire appears to have burnt these forests most intensively, whereas the wetter forests are patchy. The towns of Marysville, Kinglake and St Andrews are surrounded by these drier forest types, so it is not surprising that we see the highest levels of devastation in these areas.

1) Much of the fire burnt most intensively through dry forest with euc species such as Euc radiata and Euc dives. These trees have no market value for the logging industry and usually no logging takes place in them. On the Modis fire satellite image, the fire appears to have burnt these forests most intensively, whereas the wetter forests are patchy. The towns of Marysville, Kinglake and St Andrews are surrounded by these drier forest types, so it is not surprising that we see the highest levels of devastation in these areas. A testimony to the generosity and solidarity of Victorians in a crisis, millions of dollars are pouring in for human bush-fire victims, but the people rescuing animals are digging into their own pockets.

A testimony to the generosity and solidarity of Victorians in a crisis, millions of dollars are pouring in for human bush-fire victims, but the people rescuing animals are digging into their own pockets.

Gunnamatta Outfall - 150 GL a year.

Gunnamatta Outfall - 150 GL a year.

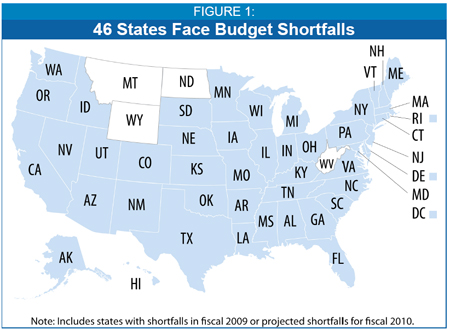

On Friday, February 6, Statistics Canada reported that Canada had lost 129,000 jobs in January. The big question all Canadians should be asking is this: What sense does it make for Canada to continue to bring in 250,000 regular immigrants each year and to allow an additional 200,000 temporary foreign workers to work here when unemployment in our own population continues to rise? As some Canadians know, Canada has the highest net per capita immigration intake of any country in the world. If Ottawa applies the most elementary logic, the Stats Can news should be all the evidence that MP's of all stripes need to drive the last nail into high immigration's coffin.

On Friday, February 6, Statistics Canada reported that Canada had lost 129,000 jobs in January. The big question all Canadians should be asking is this: What sense does it make for Canada to continue to bring in 250,000 regular immigrants each year and to allow an additional 200,000 temporary foreign workers to work here when unemployment in our own population continues to rise? As some Canadians know, Canada has the highest net per capita immigration intake of any country in the world. If Ottawa applies the most elementary logic, the Stats Can news should be all the evidence that MP's of all stripes need to drive the last nail into high immigration's coffin.

Should I feel humiliated by being outdone by the excellent reportage of James Sinnamon on All Things

Should I feel humiliated by being outdone by the excellent reportage of James Sinnamon on All Things  This article is the second candobetter

This article is the second candobetter  A new series is running, the last program as follows: What kind of parent are you? Well, if the report by the Children’s Society is anything to go by, the chances are you may not want to know the answer to that question. It concluded that the greatest threat to British children was their parent’s rampant individualism and aggressive pursuit of personal success. It claims that Britain has more 'broken families' than almost any other comparable country because of selfish parents who are not prepared to work at their relationships.

A new series is running, the last program as follows: What kind of parent are you? Well, if the report by the Children’s Society is anything to go by, the chances are you may not want to know the answer to that question. It concluded that the greatest threat to British children was their parent’s rampant individualism and aggressive pursuit of personal success. It claims that Britain has more 'broken families' than almost any other comparable country because of selfish parents who are not prepared to work at their relationships.

The final version of Jaws dwarfs all the others. This new monster is eating towns up alive. This is not just a battle to the death; this is WAR! In the novel, Jaws, the monster was not really a white pointer shark, it was the property development lobby, which metastasized with the colonisation of a modest fishing town by rich people from other places. Developers drew power from the wealthy tourists and sea-changers. They took over the original fishing town for their own purposes and democracy seemed fatally wounded. Right to the point of the shark (the developers) trying to eat the boat (symbol of the fishing industry which had begun the town). Until an odd bunch of people had the guts to stand up to the big developers.

The final version of Jaws dwarfs all the others. This new monster is eating towns up alive. This is not just a battle to the death; this is WAR! In the novel, Jaws, the monster was not really a white pointer shark, it was the property development lobby, which metastasized with the colonisation of a modest fishing town by rich people from other places. Developers drew power from the wealthy tourists and sea-changers. They took over the original fishing town for their own purposes and democracy seemed fatally wounded. Right to the point of the shark (the developers) trying to eat the boat (symbol of the fishing industry which had begun the town). Until an odd bunch of people had the guts to stand up to the big developers.

Recent comments